Am386

The Am386 CPU is a 100%-compatible clone of the Intel 80386 design released by AMD in March 1991. It sold millions of units, positioning AMD as a legitimate competitor to Intel, rather than being merely a second source for x86 CPUs (then termed 8086-family).[1]

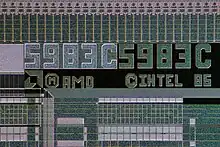

An AMD 80386DX-40 in a 132-pin PQFP, soldered onboard | |

| General information | |

|---|---|

| Launched | 1991 |

| Marketed by | AMD |

| Designed by | AMD |

| Common manufacturer(s) |

|

| Product code | 23936 |

| Performance | |

| Max. CPU clock rate | 20 MHz to 40 MHz |

| FSB speeds | 20 MHz to 40 MHz |

| Cache | |

| L1 cache | Motherboard dependent |

| L2 cache | none |

| Architecture and classification | |

| Application | Desktop, Embedded (DE-Models) |

| Technology node | 1.5 μm to 0.8 μm |

| Microarchitecture | 80386 |

| Instruction set | x86 (IA-32) |

| Physical specifications | |

| Cores |

|

| Package(s) | |

| History | |

| Predecessor(s) | Am286 |

| Successor(s) | Am486 |

History and design

While the AM386 CPU was essentially ready to be released prior to 1991, Intel kept it tied up in court.[2] Intel learned of the Am386 when both companies hired employees with the same name who coincidentally stayed at the same hotel, which accidentally forwarded a package for AMD to Intel's employee.[3] AMD had previously been a second-source manufacturer of Intel's Intel 8086, Intel 80186 and Intel 80286 designs, and AMD's interpretation of the contract, made up in 1982, was that it covered all derivatives of them. Intel, however, claimed that the contract only covered the 80286 and prior processors and forbade AMD the right to manufacture 80386 CPUs in 1987. After a few years in the courtrooms, AMD finally won the case and the right to sell their Am386 in March 1991.[4] This also paved the way for competition in the 80386-compatible 32-bit CPU market and so lowered the cost of owning a PC.[1]

While Intel's 386 CPUs had topped out at 33 MHz in 1989, AMD introduced 40 MHz versions of both its 386DX and 386SX out of the gate, extending the lifespan of the architecture. In the following two years the AMD 386DX-40 saw popularity with small manufacturers of PC clones and with budget-minded computer enthusiasts because it offered near-80486 performance at a much lower price than an actual 486.[5] Generally the 386DX-40 performs nearly on par with a 25 MHz 486 due to the 486 needing fewer clock cycles per instruction, thanks to its tighter pipelining (more overlapping of internal processing) in combination with an on-chip CPU cache. However, its 32-bit 40 MHz data bus gave the 386DX-40 comparatively good memory and I/O performance.[6]

An Am386DX-25

An Am386DX-25 The Am386DE-33 is an embedded version of the Am386DX-33

The Am386DE-33 is an embedded version of the Am386DX-33 A PGA Am386DX-40

A PGA Am386DX-40 A PQFP Am386DX-40 on a 132-pin PGA adapter

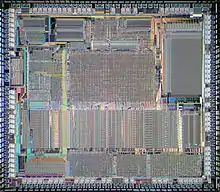

A PQFP Am386DX-40 on a 132-pin PGA adapter AMD Am386DE Block Diagram There is not a Paging Unit like a DX CPU

AMD Am386DE Block Diagram There is not a Paging Unit like a DX CPU A scan of an AMD Am386™DX-40 mounted on a PGA adapter.

A scan of an AMD Am386™DX-40 mounted on a PGA adapter.

Am386DX data

- 32-bit data bus, can select between either a 32-bit bus or a 16-bit bus by use of the BS16 input

- 32-bit physical address space, 4 Gbyte physical memory address space

- fetches code in four-byte units

- released in March 1991

| Model number | Frequency | FSB | Voltage | Power | Socket |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD Am386DX/DXL-20 | 20 MHz | 5 V | 1.05 Watt | 132-pin CPGA | |

| AMD Am386DX/DXL-25 | 25 MHz | 1.31 Watt | |||

| AMD Am386DX/DXL-33 | 33 MHz | 1.73 Watt | |||

| AMD Am386DX/DXL-40 | 40 MHz | 2.10 Watt | |||

| AMD Am386DX-40 | 3.03 Watt | 132-pin PQFP | |||

Am386DE data

- 32-bit data bus, can select between either a 32-bit bus or a 16-bit bus by use of the BS16 input

- 32-bit physical address space, 4 Gbyte physical memory address space

- fetches code in four-byte units

- no paging unit

| Model number | Frequency | FSB | Voltage | Power | Socket | Release date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD Am386DE-25KC | 25 MHz | 3-5 V | 0.32-1.05 Watt | 132-pin PQFP | ? | |

| AMD Am386DE-33KC | 33 MHz | 5 V | 1.05-1.35 Watt | |||

| AMD Am386DE-33GC | 132-pin CPGA | |||||

AM386 SX

In 1991 AMD also introduced advanced versions of the 386SX processor – again not as a second source production of the Intel chip, but as a reverse engineered pin compatible version. In fact, it was AMD's first entry in the x86 market other than as a second source for Intel.[7] AMD 386SX processors were available at higher clock speeds at the time they were introduced and still cheaper than the Intel 386SX. Produced in 0.8 μm technology and using a static core, their clock speed could be dropped down to 0 MHz, consuming just some mWatts. Power consumption was up to 35% lower than with Intel's design and even lower than the 386SL's, making the AMD 386SX the ideal chip for both desktop and mobile computers. The SXL versions featured advanced power management functions and used even less power.[7]

An Am386SX-25

An Am386SX-25 An Am386SX-33

An Am386SX-33--(386-CPU).png.webp) An Am386SX-40

An Am386SX-40

Am386SX data

- 16-bit data bus, no bus sizing option

- 24-bit physical address space, 16 Mbyte physical memory address space

- prefetch unit reads two bytes as one unit (like the 80286).

| Model number | Frequency | FSB | Voltage | Power | Socket | Release date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD Am386SX/SXL-20 | 20 MHz | 5 V | 1.68/0.85 Watt | 100-pin PQFP | 1991 | |

| AMD Am386SX/SXL-25 | 25 MHz | 1.84/1.05 Watt | 29 April 1991 | |||

| AMD Am386SX/SXL-33 | 33 MHz | 1.35 Watt | 1992 | |||

| AMD Am386SX-40 | 40 MHz | 1.55 Watt | 1991 | |||

80387 coprocessor

Floating point performance of the Am386 could be boosted with the addition of a 80387DX or 80387SX coprocessor, although performance would still not approach that of the on-chip FPU of the 486DX. This made the Am386DX a suboptimal choice for scientific applications and CAD using floating point intensive calculations. However, both were niche markets in the early 1990s and the chip sold well, first as a mid-range contender, and then as a budget chip. Although motherboards using the older 386 CPUs often had limited memory expansion possibilities and therefore struggled under Windows 95's memory requirements, boards using the Am386 were sold well into the mid-1990s; at the end as budget motherboards for those who were only interested in running MS-DOS or Windows 3.1x applications. The Am386 and its low-power successors were also popular choices for embedded systems, for a much longer period than their life span as PC processors.

An IIT 387SX-25 Coprocessor

An IIT 387SX-25 Coprocessor A Cyrix FasMath 387DX-33 Coprocessor

A Cyrix FasMath 387DX-33 Coprocessor An ULSI 387SX-40 Coprocessor

An ULSI 387SX-40 Coprocessor

References

- "The AMD Am386 DX Processor". cpu-collection.de. 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- Shvets, Gennadiy (5 November 2011). "AMD 80386 microprocessor". CPU-World. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- Dobelli, Rolf (2013). The Art of Thinking Clearly (1st ed.). HarperCollins. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-06-221968-8.

- Pollack, Andrew (2 March 1991). "Intel Loses Trademark Decision". The New York Times.

- "386DX-40 and competitors". the red hill cpu guide. 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- Linderholm, Owen; Miller, Dan (1 December 1992). "486SX-25s vs. 386DX-40s: the upstart fights back. (evaluations of 30 microcomputers based on Intel Corp.'s 80486SX-25, 80386DX-40 microprocessors) (Hardware Review) (Systems: 486SX-25 vs. 386-40) (Evaluation)". Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "The AMD Am386 SX Processor". cpu-collection.de. 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, AMD Datasheet no 15022.

External links

- AMD.com: Am386 Family 32-bit Processors

- AMD Am386SX/SXL/SXLV Datasheet

- cpu-collection.de: Pictures

- AMD: 30 Years of Pursuing the Leader. Part 2

- Shvets, Gennadiy (5 November 2011). "AMD 80386 microprocessor". CPU-World. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- AMD Am386 Microprocessors for Personal Computers Datasheet 15021 and 15022

- AMD (Advanced Micro Devices) AM386DE-33KC 32-BIT, 33 MHz, MICROPROCESSOR, PQFP132 pdf datasheet