ASRAAM

The Advanced Short Range Air-to-Air Missile (ASRAAM), also known by its United States designation AIM-132, is an imaging infrared homing air-to-air missile, produced by MBDA UK, that is designed for close-range combat. It is in service in the Royal Air Force (RAF), replacing the AIM-9 Sidewinder. ASRAAM is designed to allow the pilot to fire and then turn away before the opposing aircraft can close for a shot. It flies at well over Mach 3 to ranges in excess of 25 kilometres (16 mi).[3] It retains a 50 g manoeuvrability provided by body lift technology coupled with tail control.[7][1]

| ASRAAM | |

|---|---|

Two ASRAAM (centre) on an RAF Typhoon in 2007 | |

| Type | Short-range air-to-air missile |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1998 |

| Used by | RAF, IAF |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | MBDA UK |

| Unit cost | >£200,000 |

| Variants | Common Anti-aircraft Modular Missile (Sea Ceptor) |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 88 kg (194 lb) |

| Length | 2.90 m (9 ft 6 in) |

| Diameter | 166 mm (6.5 in) (motor diameter)[1] |

| Wingspan | 450 mm |

| Warhead | 10 kg (22 lb) blast/fragmentation |

Detonation mechanism | laser proximity fuze and impact |

| Engine | dual-burn, high-impulse solid rocket motor[2] |

Operational range | 25+ km[3][4] |

| Flight altitude | N/A |

| Maximum speed | Mach 3+[6] |

Guidance system | infrared homing, 128×128 element focal plane array, with lock-on after launch (LOAL) and strapdown inertial guidance[6] |

Launch platform | |

The project started as a British-German collaboration in the 1980s. It was part of a wider agreement in which the US would develop the AIM-120 AMRAAM for medium-range use, while the ASRAAM would replace the Sidewinder with a design that would cover the great range disparity between Sidewinder and AMRAAM. Germany left the programme in 1989. The British proceeded on their own and the missile was introduced into RAF service in 1998. It is being introduced to the Indian Air Force, the Qatar Air Force and the Royal Air Force of Oman, and formerly saw service in the Royal Australian Air Force. Parts of the missile have been used in the Common Anti-aircraft Modular Missile.

History

Prior work

The first extensive use of IR missiles took place during the Vietnam War, where the results were dismal. The AIM-4 Falcon, the USAF's primary missile, scored hits only 9% of the time it was fired, while the US Navy's AIM-9 Sidewinder fared only slightly better, depending on the model. It became clear that there were two basic issues causing the problem. One was that the pilots were firing as soon as the missile saw the target in the seeker, any time it was in front of the launch aircraft. However, the seekers had a very limited field of view so if the target aircraft was flying at right angles to the launcher, it would fly out of the seeker's view even as it left the launch rail. The other was that the missile would be fired at ranges where it could not reach the target, running out of speed and simply falling to the ground. The US addressed this through new training that helped pilots understand the limits of their missiles and fly their aircraft into positions that maximized the chance of a hit.

One attempt to improve matters was made starting in the late 1960s by the Hawker Siddeley "Taildog", initially a private project but later officially supported as SRAAM. SRAAM's basic premise is that if pilots wanted to fire when the target was anywhere in front, then the missile should work in those situations. The result was a very short range but extremely maneuverable weapon that could turn rapidly enough to keep the target in view no matter the launch parameters. However, by 1974 the programme had been downgraded to a pure development project, and was later cancelled. The US started a similar project, AIM-95 Agile, to arm the new F-14 and F-15. This was similar to SRAAM in concept, but somewhat larger in order to offer range about the same or better than Sidewinder. Development was cancelled in 1975. Meanwhile, an entire different set of criteria led to the Dornier Viper, whose design maximized range.[8]

The main reason these projects were cancelled was that a new version of the Sidewinder was introduced, the AIM-9L. A variety of changes gave the L slightly better manoeuvrability, speed and range, but the main change was a new seeker that had much higher tracking angles and all-aspect capabilities that allowed head-on engagements. Although not nearly as great a step forward as the other designs, the "Lima" offered a significant improvement in capability over the older models with very little additional cost. British pilots achieved an 80% kill ratio with the L model during the Falklands War, a number matched by the Israeli Air Force a few months later over the Bekaa Valley. US experience with the Sidewinder since then has been mixed, with a percentage kill of just under 60% for the F-15, but almost zero for F-16s and F/A-18s, including a notable miss in 2017 when a 1970s-era Syrian Su-22 "Fitter" defeated a modern AIM-9X launched by a US Navy F/A-18.[9]

AMRAAM and ASRAAM

In a series of tests in the mid-1970s, the USAF found that their existing AIM-7 Sparrow missile had an effective range against fighter targets no better than the ostensibly much shorter-range Sidewinder. Because it was guided using the signals of the attacking aircraft's radar reflecting off the target, the launching aircraft had to keep flying towards the target for its radar to continue illuminating it. During the time the missile was flying, the target aircraft was closing the distance and had the chance to launch IR missiles before being hit. This resulted in mutual kills, obviously undesirable.[10]

The Fighter Mafia examined these results and concluded that they proved what they had been saying all along: a smaller, cheaper aircraft armed with simple but effective weapons is just as good as a more complex and expensive system but could be purchased in greater numbers.[10] The USAF looked at the same results and concluded the solution was to design a new weapon to replace the Sparrow. The primary aims were to extend the range to keep the IR-guided missile firing fighters out of launching range, using a self-contained active seeker to allow the launching fighter to turn away, and, if possible, to reduce the weight enough to allow it to be carried on launchers designed only for the Sidewinder. The result was the AIM-120 AMRAAM project, with the initial versions having a range of 50 to 75 km.

The AMRAAM also presented a new problem: between the Sidewinder's short range and AMRAAM's long range was a significant gap. AMRAAM was not really intended to be a snap-shot weapon like the Sidewinder, which remained desirable and the passive attack of a heatseeker can be an enormous advantage in combat. A new IR guided missile designed to act as a counterpart to AMRAAM would be a very different design than the AIM-9L, which had always been intended solely as a stop-gap.

In the 1980s, NATO countries signed a Memorandum of Agreement that the United States would develop the AMRAAM, while a primarily British and German team would develop a short-range air-to-air missile to replace the Sidewinder. The team included the UK (Hawker Siddeley, by this point known as BAe Dynamics) and Germany (Bodensee Gerätetechnik) sharing 42.5 per cent of the effort each, Canada at 10 per cent and Norway at 5 per cent. The US assigned this missile the name AIM-132 ASRAAM.[11]

New ASRAAM

The rapid decline and eventual fall of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s led to considerably less interest in the ASRAAM. By February 1988 the US was already agitating for changes. In July 1989 the Germans exited the programme effectively ending the agreement. Various reasons are often cited including the ending of the Cold War and full realisation of the capabilities of the Russian R-73 missile, but many commentators think this was a smokescreen for financial and defence industrial share issues.[12]

This left Britain in charge of the project and they began redefining it purely to RAF needs, sending out tenders for the new design in August 1989. This led to the selection of a new Hughes focal plane array imaging array seeker instead of the more conventional design previously used, dramatically improving performance and countermeasure resistance. A UK contest in 1990 examined the new ASRAAM, the French MICA and a new design from Bodensee Gerätetechnik, their version of the ASRAAM tuned for German needs. In 1992 the Ministry of Defence announced that ASRAAM had won the contest, and production began in March that year. The German design, by now part of Diehl BGT Defence, became the IRIS-T.[11]

While ASRAAM was entering production, momentum behind US-led industrial and political lobbying grew significantly and, combined with the strengthening European economy, forced the US government to conclude testing in June 1996 and move away from the ASRAAM program.[13]

UK development and manufacture went ahead and the first ASRAAM was delivered to the Royal Air Force (RAF) in late 1998. It equips the RAF's Typhoon. It was also used by the RAF's Harrier GR7 and Tornado GR4 forces until their retirement. In February 1998 ASRAAM was selected by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) for use on their F/A-18 Hornets following competitive evaluation of the improved ASRAAM, the Rafael Python 4 and the AIM-9X.[11] In March 2009 the RAAF successfully carried out the first in-service "Lock on After Launch" firing of an ASRAAM at a target located behind the wing-line of the "shooter" aircraft.[14]

Description

Characteristics

ASRAAM is a high speed, extremely manoeuvrable, heat-seeking, air-to-air missile. Built by MBDA UK, it is designed as a "fire-and-forget" missile.[12] ASRAAM is intended to detect and launch against targets at much longer ranges, as far as early versions of the AMRAAM, in order to shoot down the enemy long before it closes enough to be able to fire its own weapons. In this respect the ASRAAM shares more in common with the AMRAAM than other IR missiles, although it retains high manoeuvrability. To provide the needed power, the ASRAAM is built on a 16.51 cm (6½ inch) diameter rocket motor compared with Sidewinder's (AIM-9M and X) and IRIS-T's 12.7 cm (5-inch) motors (which trace their history to the 1950s unguided Zuni rocket). This gives the ASRAAM significantly more thrust and therefore increased speed and range up to 50 km.[4]

The main improvement is a new 128×128 resolution imaging infrared focal plane array (FPA) seeker manufactured by Hughes before they were acquired by Raytheon. This seeker has a long acquisition range, high countermeasures resistance, approximately 90-degree off-boresight lock-on capability, and the possibility to designate specific parts of the targeted aircraft (like cockpit, engines, etc.).[15] The ASRAAM also has a LOAL (Lock-On After Launch) ability which is a distinct advantage when the missile is carried in an internal bay such as in the F-35 Lightning II. The ASRAAM warhead is triggered either by laser proximity fuse or impact. A laser proximity fuse was selected because RF fuses are vulnerable to EW intervention from enemy jammers.[16] The increased diameter of ASRAAM also provides space for increased computing power, and so improved counter counter-measure capabilities compared with other dogfighting missiles such as AIM-9X.

ASRAAM P3I

In 1995, Hughes and British Aerospace collaborated on the "P3I ASRAAM", a version of ASRAAM as a candidate for the AIM-9X program. The ultimate winner was the Hughes submission using the same seeker but with the rocket motor, fuse and warhead of the AIM-9M. The latter was a US Air Force stipulation to ease the logistics burden and save money by reusing as much as possible of the existing AIM-9 Sidewinder, of which 20,000 remained in the US inventory.

Future development

At the DSEi conference in September 2007 it was announced that the UK MoD was funding a study by MBDA to investigate a replacement for the Rapier and Sea Wolf missiles. The Common Anti-Air Modular Missile (CAMM) would share components with ASRAAM,[17] such as the very low signature rocket motor from Roxel and the warhead and proximity fuze from Thales. CAAM has a Common Data Link (CDL) so it can take mid-course corrections from suitably-equipped land or air platforms and then switch to active homing when close enough.[18]

In 2014, India's defence ministry signed a £250m ($428m) contract with MBDA to equip its SEPECAT/Hindustan Aeronautics Jaguar strike aircraft with the company's ASRAAM short range air-to-air missile. MBDA's offering overcame competition from competitors including Rafael's Python-5 missile, emerging as the winner in 2012. This built on an existing 2012 order for 493 MICA missiles to replace Matra S-530D and Magic II missiles as part of an Indian Air Force Mirage 2000 update.[19]

In September 2015, the UK's MoD signed a £300 million contract for a new and improved version of the ASRAAM that would leverage new technological developments, including those from the CAMM missile. This variant would replace the current one when it goes out of service in 2022. A further £184 million contract was awarded in August 2016 to provide additional stocks of the new ASRAAM for the UK's F-35B. This new variant will be operationally ready on the Eurofighter Typhoon in 2018 and on the UK's F-35Bs from 2022 onwards.[20][21]

In February 2017, successful firing of ASRAAMs from F-35 Lightning IIs were conducted at Naval Air Station Patuxent River and Edwards Air Force Base in the USA. This represented the first time that a British-designed missile had been fired from an F-35 JSF and the first time any non-US missile had ever been fired from the aircraft.[22]

As of 31 January 2019 the Indian Air Force is testing the compatibility of the ASRAAM weapons system with the Sukhoi Su-30MKI, and aims to make the ASRAAM its standardised dogfighting missile across multiple aircraft types, including the Tejas. Final testing and operational clearance are to be achieved by the end of 2019.[23] Bharat Dynamics Limited will produce the missile at its Bhanoor unit. The facility will also offer maintenance, repair & overhaul services.[24]

ASRAAM Block 6 standard, developed under the ASRAAM Sustainment programme, entered service on the Typhoon in April 2022,[25] and will enter F-35 service in 2024. The block 6 introduces new and updated sub-systems, and replaces external cooling with a new internal cooler. The seeker has been replaced with a new UK built seeker of higher resolution. There are no US-made components, meaning that it does not come under ITAR restrictions and can therefore be exported without US approval.[26][27]

Operational history

On 14 December 2021 a RAF Typhoon operating against Islamic State in southern Syria shot down a hostile drone with an ASRAAM missile. This was the first time the British military had shot down an enemy aircraft since the Falklands War.[28]

In Ukraine they have been ground launched by Ukrainian forces against HESA Shahed 136s.[29] It has also been used by Ukrainian forces to provide short range air defences SHORAD against Russian aerial threats, namely attack helicopters. The missile has a "fire and forget" capacity, compared to the Starstreak missile that requires a line of sight to the target. Being mounted on the back of a Supacat 6x6 vehicle it allows it to remain mobile. [30]

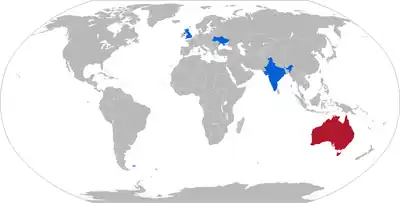

Operators

Current operators

United Kingdom

United Kingdom- Royal Air Force, on the Typhoon, and also carried by the F-35 Lightning II in RAF and Royal Navy service.

India

India- Indian Air Force; on 8 July 2014 India signed a deal to procure 384 ASRAAMs from MBDA UK to replace the aging Matra Magic R550, to be integrated onto the SEPECAT Jaguar strike aircraft.[31]

Ukraine

Ukraine- In August 2023 a Ground (rail) launched version of ASRAAM was reported mounted on a Supacat HMT chassis in Ukraine.[29] This is not the CAMM missile rather the AIM-132.[29]

Future operators

References

Citations

- Asraam background (PDF), MBDA, archived from the original on 4 October 2013

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - "Asraam", RAF, MoD.

- "ASRAAM". MBDS Systems. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- "ASRAAM". Science & Technology (documentary). jaglavaksoldier. Retrieved 10 July 2009 – via YouTube.

- "AIM-132 ASRAAM". FAS. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Asraam", Typhoon, Star streak, archived from the original on 23 April 2012.

- "Dornier Viper abandoned", Flight International: 847, 27 June 1974

- "How Did a 30-Year-Old Jet Dodge the Pentagon's Latest Missile?". Popular Mechanics. 26 June 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Correll, John (February 2008). "The Reformers". Air Force Magazine.

- Kopp, Carlo (January 1998). "Matra-BAe AIM-132 ASRAAM: The RAAF's New WVR AAM". Air Power Australia. 4 (4). Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Advanced Short Range Air to Air Missile (ASRAAM)". Think Defence. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Hughes wins AIM-9X". Flightglobal. 1 January 1997. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "RAAF has successfully fired ASRAAM at a target located behind the wing-line of the 'shooter' aircraft". Your Industry News. 9 March 2009. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- "Australian ASRAAM Demonstrate Full Sphere Capability". Defense Update. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "'Talisman' ADS – БКО 'Талисман'". YouTube..

- "Missiles and Fire Support at DSEi 2007", Defense update, archived from the original on 5 September 2008, retrieved 27 December 2007.

- "Common Anti Air Modular Missile (CAMM) – Think Defence". thinkdefence.co.uk. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "MBDA signs Indian ASRAAM contract". Flightglobal.com. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Britain Stockpiles New ASRAAM Missiles for the F-35". Defensenews.com. 16 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "UK orders ASRAAMs to arm F-35s". IHS Janes. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "F-35 Successfully Conducts First Firings of MBDA's ASRAAM". F-35 Lightning II. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- Aroor, Shiv (31 January 2019). "EXCLUSIVE: IAF Arming Su-30s With ASRAAMs, May Standardise Missile Across Fleet".

- BDL &MBDA sign agreement to establish Advanced Short Range Air-to-Air Missile facility in India

- Allison, George (2 May 2022). "ASRAAM Block 6 enters service on Typhoon". UK Defence Journal. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- Allison, George (22 October 2021). "ASRAAM Block 6 to enter service on F-35 and Typhoon by 2024". UK Defence Journal. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- "ASRAAM Block 6 enters service on Typhoon". 2 May 2022.

- Jonathan Beale. 16 December 2021 RAF Typhoon jet shoots down 'small hostile drone' in Syria BBC News

- Newdick, Thomas; Rogoway, Tyler (4 August 2023). "Air-To-Air Missiles From UK Now Being Used By Ukraine As SAMs". The Drive. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- THOMAS NEWDICK; TYLER ROGOWAY (4 August 2023). "Air-To-Air Missiles From UK Now Being Used By Ukraine As SAMs". The War Zone.

- "India, UK sign deals worth 370 million". Live Mint. 8 July 2014.

- "MBDA ASRAAM in service with the RAAF has been successfully fired from the aircraft". MBDA. Retrieved 19 November 2020.