History of Afghanistan

The history of Afghanistan, preceding the establishment of the Emirate of Afghanistan in 1823 is shared with that of neighbouring Iran, central Asia and Indian subcontinent. The Sadozai monarchy ruled the Afghan Durrani Empire, considered the founding state of modern Afghanistan.[1]

| History of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

Human habitation in Afghanistan dates back to the Middle Paleolithic era, and the country's strategic location along the historic Silk Road has led it to being described, picturesquely, as the ‘roundabout of the ancient world’.[2] The land has historically been home to various peoples and has witnessed numerous military campaigns, including those by the Persians, Alexander the Great, the Maurya Empire, Arab Muslims, the Mongols, the British, the Soviet Union, and most recently by a US-led coalition.[3] The various conquests and periods in both the Indian and Iranian cultural spheres[4][5] made the area a center for , Buddhism, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism and later Islam throughout history.[6]

The Durrani Empire is considered to be the foundational polity of the modern nation-state of Afghanistan, with Ahmad Shah Durrani being credited as its Father of the Nation.[7][8] However, Dost Mohammad Khan is sometimes considered to be the founder of the first modern Afghan state.[9] Following the Durrani Empire's decline and the death of Ahmad Shah Durrani and Timur Shah, it was divided into multiple smaller independent kingdoms, including but not limited to Herat, Kandahar and Kabul. Afghanistan would be reunited in the 19th century after seven decades of civil war from 1793 to 1863, with wars of unification led by Dost Mohammad Khan from 1823 to 1863, where he conquered the independent principalities of Afghanistan under the Emirate of Kabul. Dost Mohammad died in 1863, days after his last campaign to unite Afghanistan, and Afghanistan was consequently thrown back into civil war with fighting amongst his successors. During this time, Afghanistan became a buffer state in the Great Game between the British Raj in South Asia and the Russian Empire. The British Raj attempted to subjugate Afghanistan but was repelled in the First Anglo-Afghan War. However, the Second Anglo-Afghan War saw a British victory and the successful establishment of British political influence over Afghanistan. Following the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919, Afghanistan became free of foreign political hegemony, and emerged as the independent Kingdom of Afghanistan in June 1926 under Amanullah Khan. This monarchy lasted almost half a century, until Zahir Shah was overthrown in 1973, following which the Republic of Afghanistan was established.

Since the late 1970s, Afghanistan's history has been dominated by extensive warfare, including coups, invasions, insurgencies, and civil wars. The conflict began in 1978 when a communist revolution established a socialist state, and subsequent infighting prompted the Soviet Union to invade Afghanistan in 1979. Mujahideen fought against the Soviets in the Soviet–Afghan War and continued fighting amongst themselves following the Soviets' withdrawal in 1989. The Islamic fundamentalist Taliban controlled most of the country by 1996, but their Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan received little international recognition before its overthrow in the 2001 US invasion of Afghanistan. The Taliban returned to power in 2021 after capturing Kabul and overthrowing the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, thus bringing an end to the 2001–2021 war.[10] Although initially claiming it would form an inclusive government for the country, in September 2021 the Taliban re-established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan with an interim government made up entirely of Taliban members.[11] The Taliban government remains internationally unrecognized.[12]

Prehistory

Excavations of prehistoric sites by Louis Dupree and others at Darra-e Kur in 1966 where 800 stone implements were recovered along with a fragment of Neanderthal right temporal bone, suggest that early humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 52,000 years ago. A cave called Kara Kamar contained Upper Paleolithic blades Carbon-14 dated at 34,000 years old.[13] Farming communities in Afghanistan were among the earliest in the world.[14] Artifacts indicate that the indigenous people were small farmers and herdsmen, very probably grouped into tribes, with small local kingdoms rising and falling through the ages. Urbanization may have begun as early as 3000 BCE.[15] Gandhara is the name of an ancient kingdom from the Vedic period and its capital city located between the Hindukush and Sulaiman Mountains (mountains of Solomon),[16] although Kandahar in modern times and the ancient Gandhara are not geographically identical.[17][18]

Early inhabitants, around 3000 BCE were likely to have been connected through culture and trade to neighboring civilizations like Jiroft and Tappeh Sialk and the Indus Valley civilization. Urban civilization may have begun as early as 3000 BCE and it is possible that the early city of Mundigak (near Kandahar) was a part of Helmand culture.[19] The first known people were Indo-Iranians,[14] but their date of arrival has been estimated widely from as early as about 3000 BCE[20] to 1500 BCE.[21] (For further detail see Indo-Aryan migration.)

Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley civilisation (IVC) was a Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE) extending from present-day northwest Pakistan to present-day northwest India and present-day northeast Afghanistan.[22] An Indus Valley trading colony has been found on the Oxus River at Shortugai in northern Afghanistan.[23] Apart from Shortughai, Mundigak is another known site.[24] There are several other smaller IVC sites to be found in Afghanistan as well.

Bactria-Margiana

The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex became prominent between 2200 and 1700 BCE (approximately). The city of Balkh (Bactra) was founded about this time (c. 2000–1500 BCE).[20]

Ancient period (c. 1500 – 250 BCE)

Gandhara Kingdom (c. 1500 – 535 BCE)

.png.webp)

The Gandhara region centered around the Peshawar Valley and Swat river valley, though the cultural influence of "Greater Gandhara" extended across the Indus river to the Taxila region in Potohar Plateau and westwards into the Kabul and Bamiyan valleys in Afghanistan, and northwards up to the Karakoram range.[25][26]

During the 6th century BCE, Gandhāra was an important imperial power in north-west South Asia, with the valley of Kaśmīra being part of the kingdom, while the other states of the Punjab region, such as the Kekayas, Madrakas, Uśīnaras, and Shivis being under Gāndhārī suzerainty. The Gāndhārī king Pukkusāti, who reigned around 550 BCE, engaged in expansionist ventures which brought him into conflict with the king Pradyota of the rising power of Avanti. Pukkusāti was successful in this struggle with Pradyota.[27][28]

By the later 6th century BCE, the founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, Cyrus, soon after his conquests of Media, Lydia, and Babylonia, marched into Gandhara and annexed it into his empire.[29] The scholar Kaikhosru Danjibuoy Sethna advanced that Cyrus had conquered only the trans-Indus borderlands around Peshawar which had belonged to Gandhāra while Pukkusāti remained a powerful king who maintained his rule over the rest of Gandhāra and the western Punjab.[30]

Kamboja Kingdom (c. 700 – 200 BCE)

The Kambojas entered into conflict with Alexander the Great as he invaded Central Asia. The Macedonian conqueror made short shrift of the arrangements of Darius and after over-running the Achaemenid Empire he dashed into today's eastern Afghanistan and western Pakistan. There he encountered resistance from the Kamboja Aspasioi and Assakenoi tribes.[31][32] The Region of the Hindukush that was inhabitanted by the Kambojas has gone through many rules such as Vedic Mahajanapada, Pali Kapiśi, Indo-Greeks, Kushan and Gandharans to Paristan and modern day being split between Pakistan and Eastern Afghanistan.

The descendants of Kambojas have mostly been assimilated into newer identities, however, some tribes remain today that still retain the names of their ancestors. The Yusufzai Pashtuns are said to be the Esapzai/Aśvakas from the Kamboja age. The Kom/Kamoz people of Nuristan retain their Kamboj name. The Ashkun of Nuristan also retain the name of Aśvakas. The Yashkun Shina dards are another group that retain the name of the Kamboja Aśvakans. The Kamboj of Punjab are another group that still retain the name however have integrated into new identity. The country of Cambodia derives its name from the Kamboja.[33]

Achaemenid Empire

Afghanistan fell to the Achaemenid Empire after it was conquered by Darius I of Persia. The area was divided into several provinces called satrapies, which were each ruled by a governor, or satrap. These ancient satrapies included: Aria: The region of Aria was separated by mountain ranges from the Paropamisadae in the east, Parthia in the west and Margiana and Hyrcania in the north, while a desert separated it from Carmania and Drangiana in the south. It is described in a very detailed manner by Ptolemy and Strabo[34] and corresponds, according to that, almost to the Herat Province of today's Afghanistan; Arachosia, corresponds to the modern-day Kandahar, Lashkar Gah, and Quetta. Arachosia bordered Drangiana to the west, Paropamisadae (i.e. Gandahara) to the north and to the east, and Gedrosia to the south. The inhabitants of Arachosia were Iranian peoples, referred to as Arachosians or Arachoti.[35] It is assumed that they were called Paktyans by ethnicity, and that name may have been in reference to the ethnic Paṣtun (Pashtun) tribes;[36]

Bactriana was the area north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Tian Shan, with the Amu Darya flowing west through the center (Balkh); Sattagydia was the easternmost regions of the Achaemenid Empire, part of its Seventh tax district according to Herodotus, along with Gandārae, Dadicae and Aparytae.[37] It is believed to have been situated east of the Sulaiman Mountains up to the Indus River in the basin around Bannu.[ (Ghazni); and Gandhara which corresponds to modern day Kabul, Jalalabad, and Peshawar.[38]

Alexander and the Seleucus

Alexander the Great arrived in the area of Afghanistan in 330 BCE after defeating Darius III of Persia a year earlier at the Battle of Gaugamela.[39] His army faced very strong resistance in the Afghan tribal areas where he is said to have commented that Afghanistan is "easy to march into, hard to march out of."[40] Although his expedition through Afghanistan was brief, Alexander left behind a Hellenic cultural influence that lasted several centuries. Several great cities were built in the region named "Alexandria," including: Alexandria-of-the-Arians (modern-day Herat); Alexandria-on-the-Tarnak (near Kandahar); Alexandria-ad-Caucasum (near Begram, at Bordj-i-Abdullah); and finally, Alexandria-Eschate (near Kojend), in the north. After Alexander's death, his loosely connected empire was divided. Seleucus, a Macedonian officer during Alexander's campaign, declared himself ruler of his own Seleucid Empire, which also included present-day Afghanistan.[41]

Mauryan Empire

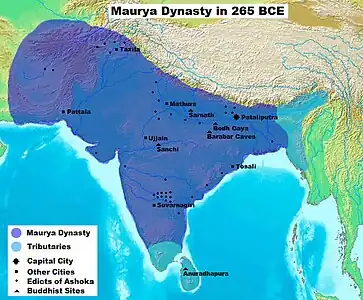

Maurya Empire under Ashoka the Great.

Maurya Empire under Ashoka the Great. Newly excavated Buddhist stupa at Mes Aynak in Logar Province of Afghanistan. Similar stupas have been discovered in neighboring Ghazni Province, including in the northern Samangan Province.

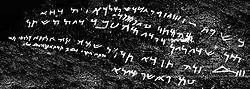

Newly excavated Buddhist stupa at Mes Aynak in Logar Province of Afghanistan. Similar stupas have been discovered in neighboring Ghazni Province, including in the northern Samangan Province. Aramaic Inscription of Laghman is an inscription on a slab of natural rock in the area of Laghmân, Afghanistan, written in Aramaic by the Indian emperor Ashoka about 260 BCE, and often categorized as one of Minor Rock Edicts of Ashoka.[42]

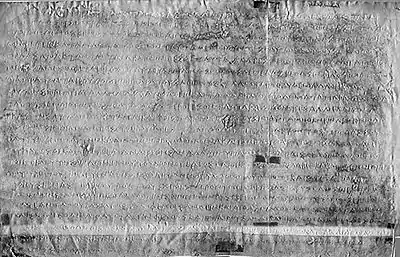

Aramaic Inscription of Laghman is an inscription on a slab of natural rock in the area of Laghmân, Afghanistan, written in Aramaic by the Indian emperor Ashoka about 260 BCE, and often categorized as one of Minor Rock Edicts of Ashoka.[42] Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka is among the Major Rock Edicts of the Indian Emperor Ashoka (reigned 269-233 BCE), which were written in the Greek language and Prakrit language.

Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka is among the Major Rock Edicts of the Indian Emperor Ashoka (reigned 269-233 BCE), which were written in the Greek language and Prakrit language.

The territory fell to the Maurya Empire, which was led by Chandragupta Maurya. The Mauryas further entrenched Hinduism and introduced Buddhism to the region, and were planning to capture more territory of Central Asia until they faced local Greco-Bactrian forces. Seleucus is said to have reached a peace treaty with Chandragupta by giving control of the territory south of the Hindu Kush to the Mauryas upon intermarriage and 500 elephants.

Alexander took these away from the Hindus and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.[43]

— Strabo, 64 BCE–24 CE

Some time after, as he was going to war with the generals of Alexander, a wild elephant of great bulk presented itself before him of its own accord, and, as if tamed down to gentleness, took him on its back, and became his guide in the war, and conspicuous in fields of battle. Sandrocottus, having thus acquired a throne, was in possession of India, when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness; who, after making a league with him, and settling his affairs in the east, proceeded to join in the war against Antigonus. As soon as the forces, therefore, of all the confederates were united, a battle was fought, in which Antigonus was slain, and his son Demetrius put to flight.[44]

Having consolidated power in the northwest, Chandragupta pushed east towards the Nanda Empire. Afghanistan's significant ancient tangible and intangible Buddhist heritage is recorded through wide-ranging archeological finds, including religious and artistic remnants. Buddhist doctrines are reported to have reached as far as Balkh even during the life of the Buddha (563 BCE to 483 BCE), as recorded by Husang Tsang.

In this context a legend recorded by Husang Tsang refers to the first two lay disciples of Buddha, Trapusa and Bhallika responsible for introducing Buddhism in that country. Originally these two were merchants of the kingdom of Balhika, as the name Bhalluka or Bhallika probably suggests the association of one with that country. They had gone to India for trade and had happened to be at Bodhgaya when the Buddha had just attained enlightenment.[45]

Classical Period (c. 250 BCE – 565 CE)

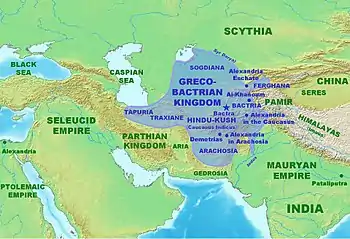

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was a Hellenistic kingdom,[46] founded when Diodotus I, the satrap of Bactria (and probably the surrounding provinces) seceded from the Seleucid Empire around 250 BCE.[47]

The Greco-Bactria Kingdom continued until c. 130 BCE, when Eucratides I's son, King Heliocles I, was defeated and driven out of Bactria by the Yuezhi tribes from the east. The Yuezhi now had complete occupation of Bactria. It is thought that Eucratides' dynasty continued to rule in Kabul and Alexandria of the Caucasus until 70 BCE when King Hermaeus was also defeated by the Yuezhi.

Indo-Greek Kingdom

One of Demetrius I's successors, Menander I, brought the Indo-Greek Kingdom (now isolated from the rest of the Hellenistic world after the fall of Bactria[48]) to its height between 165 and 130 BCE, expanding the kingdom in Afghanistan and Pakistan to even larger proportions than Demetrius. After Menander's death, the Indo-Greeks steadily declined and the last Indo-Greek kings (Strato II and Strato III) were defeated in c. 10 CE.[49] The Indo-Greek Kingdom was succeeded by the Indo-Scythians.

Indo-Scythians

The Indo-Scythians were descended from the Sakas (Scythians) who migrated from southern Siberia to Pakistan and Arachosia from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Gandhara to Mathura. The power of the Saka rulers started to decline in the 2nd century CE after the Scythians were defeated by the south Indian Emperor Gautamiputra Satakarni of the Satavahana dynasty.[50][51] Later the Saka kingdom was completely destroyed by Chandragupta II of the Gupta Empire from eastern India in the 4th century.[52]

Indo-Parthians

The Indo-Parthian Kingdom was ruled by the Gondopharid dynasty, named after its eponymous first ruler Gondophares. They ruled parts of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan,[53] and northwestern India, during or slightly before the 1st century AD. For most of their history, the leading Gondopharid kings held Taxila (in the present Punjab province of Pakistan) as their residence, but during their last few years of existence the capital shifted between Kabul and Peshawar. These kings have traditionally been referred to as Indo-Parthians, as their coinage was often inspired by the Arsacid dynasty, but they probably belonged to a wider groups of Iranic tribes who lived east of Parthia proper, and there is no evidence that all the kings who assumed the title Gondophares, which means "Holder of Glory", were even related. Christian writings claim that the Apostle Saint Thomas – an architect and skilled carpenter – had a long sojourn in the court of king Gondophares, had built a palace for the king at Taxila and had also ordained leaders for the Church before leaving for the Indus Valley in a chariot, for sailing out to eventually reach Malabar Coast.

Kushans

The Kushan Empire expanded out of Bactria (Central Asia) into the northwest of the subcontinent under the leadership of their first emperor, Kujula Kadphises, about the middle of the 1st century CE. They came from an Indo-European language speaking Central Asian tribe called the Yuezhi,[54][55] a branch of which was known as the Kushans. By the time of his grandson, Kanishka the Great, the empire spread to encompass much of Afghanistan,[56] and then the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares).[57]

Emperor Kanishka was a great patron of Buddhism; however, as Kushans expanded southward, the deities[58] of their later coinage came to reflect its new Hindu majority.[59]

They played an important role in the establishment of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent and its spread to Central Asia and China.

Historian Vincent Smith said about Kanishka:

He played the part of a second Ashoka in the history of Buddhism.[60]

The empire linked the Indian Ocean maritime trade with the commerce of the Silk Road through the Indus valley, encouraging long-distance trade, particularly between China and Rome. The Kushans brought new trends to the budding and blossoming Gandhara Art, which reached its peak during Kushan Rule.

H. G. Rowlinson commented:

The Kushan period is a fitting prelude to the Age of the Guptas.[61]

By the 3rd century, their empire in India was disintegrating and their last known great emperor was Vasudeva I.[62][63]

Early Mahayana Buddhist triad. From left to right, a Kushan devotee, Maitreya, the Buddha, Avalokitesvara, and a Buddhist monk. 2nd–3rd century, Gandhara.

Early Mahayana Buddhist triad. From left to right, a Kushan devotee, Maitreya, the Buddha, Avalokitesvara, and a Buddhist monk. 2nd–3rd century, Gandhara.

Sassanian Empire

After the Kushan Empire's rule was ended by Sassanids— officially known as the Empire of Iranians— was the last kingdom of the Persian Empire before the rise of Islam. Named after the House of Sasan, it ruled from 224 to 651 AD. In the east around 325, Shapur II regained the upper hand against the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom and took control of large territories in areas now known as Afghanistan and Pakistan. Much of modern-day Afghanistan became part of the Sasanian Empire, since Shapur I extended his authority eastwards into Afghanistan and the previously autonomous Kushans were obliged to accept his suzerainty.

From around 370, however, towards the end of the reign of Shapur II, the Sassanids lost the control of Bactria to invaders from the north. These were the Kidarites, the Hephthalites, the Alchon Huns, and the Nezaks: The four Huna tribes to rule Afghanistan.[65] These invaders initially issued coins based on Sasanian designs.[66]

Huna

The Hunas were peoples who were of a group of Central Asian tribes. Four of the Huna tribe conquered and ruled Afghanistan: the Kidarites, Hepthalites, Alchon Huns and the Nezaks.

Kidarites

The Kidarites were a nomadic clan, the first of the four Huna people in Afghanistan. They are supposed to have originated in Western China and arrived in Bactria with the great migrations of the second half of the 4th century.

Alchon Huns

The Alchons are one of the four Huna people that ruled in Afghanistan. A group of Central Asian tribes, Hunas or Huna, via the Khyber Pass, entered India at the end of the 5th or early 6th century and successfully occupied areas as far as Eran and Kausambi, greatly weakening the Gupta Empire.[67] The 6th-century Roman historian Procopius of Caesarea (Book I. ch. 3), related the Huns of Europe with the Hephthalites or "White Huns" who subjugated the Sassanids and invaded northwestern India, stating that they were of the same stock, "in fact as well as in name", although he contrasted the Huns with the Hephthalites, in that the Hephthalites were sedentary, white-skinned, and possessed "not ugly" features.[68][69] Song Yun and Hui Zheng, who visited the chief of the Hephthalite nomads at his summer residence in Badakshan and later in Gandhara, observed that they had no belief in the Buddhist law and served a large number of divinities."[70]

The White Huns

The Hephthalites (or Ephthalites), also known as the White Huns and one of the four Huna people in Afghanistan, were a nomadic confederation in Central Asia during the late antiquity period. The White Huns established themselves in modern-day Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century. Led by the Hun military leader Toramana, they overran the northern region of Pakistan and North India. Toramana's son Mihirakula, a Saivite Hindu, moved up to near Pataliputra to the east and Gwalior to central India. Hiuen Tsiang narrates Mihirakula's merciless persecution of Buddhists and destruction of monasteries, though the description is disputed as far as the authenticity is concerned.[71] The Huns were defeated by the Indian kings Yasodharman of Malwa and Narasimhagupta in the 6th century. Some of them were driven out of India and others were assimilated in the Indian society.[72]

Nezak Huns

The Nezaks are one of the four Huna people that ruled in Afghanistan.

Middle Ages (565–1504 CE)

From the Middle Ages to around 1750 the eastern regions of Afghanistan such as Kabulistan and Zabulistan (now Kabul, Kandahar and Ghazni) were recognized as being part of Indian subcontinent (Al-Hind),[73][74] while its western parts were included in Khorasan,[75][76] Tokharistan[77] and Sistan.[78] Two of the four main capitals of Khorasan (Balkh and Herat) are now located in Afghanistan. The countries of Kandahar, Ghazni and Kabul formed the frontier region between Khorasan and the Indus.[79] This land, inhabited by the Afghan tribes (i.e. ancestors of Pashtuns), was called Afghanistan, which loosely covered a wide area between the Hindu Kush and the Indus River, principally around the Sulaiman Mountains.[80][81] The earliest record of the name "Afghan" ("Abgân") being mentioned is by Shapur I of the Sassanid Empire during the 3rd century CE[82][83][84] which is later recorded in the form of "Avagānā" by the Vedic astronomer Varāha Mihira in his 6th century CE Brihat-samhita.[85] It was used to refer to a common legendary ancestor known as "Afghana", grandson of King Saul of Israel.[86] Hiven Tsiang, a Chinese pilgrim, visiting the Afghanistan area several times between 630 and 644 CE also speaks about them.[82] Ancestors of many of today's Turkic-speaking Afghans settled in the Hindu Kush area and began to assimilate much of the culture and language of the Pashtun tribes already present there.[87] Among these were the Khalaj people which are known today as Ghilzai.[88]

Kabul Shahi

The Kabul Shahi dynasties ruled the Kabul Valley and Gandhara from the decline of the Kushan Empire in the 3rd century to the early 9th century.[89] The Shahis are generally split up into two eras: the Buddhist Shahis and the Hindu Shahis, with the change-over thought to have occurred sometime around 870. The kingdom was known as the Kabul Shahan or Ratbelshahan from 565 to 670, when the capitals were located in Kapisa and Kabul, and later Udabhandapura, also known as Hund[90] for its new capital.[91][92][93]

The Hindu Shahis under ruler Jayapala, is known for his struggles in defending his kingdom against the Ghaznavids in the modern-day eastern Afghanistan region. Jayapala saw a danger in the consolidation of the Ghaznavids and invaded their capital city of Ghazni both in the reign of Sebuktigin and in that of his son Mahmud, which initiated the Muslim Ghaznavid and Hindu Shahi struggles.[94] Sebuktigin, however, defeated him, and he was forced to pay an indemnity.[94] Jayapala defaulted on the payment and took to the battlefield once more.[94] Jayapala however, lost control of the entire region between the Kabul Valley and Indus River.[95]

Before his struggle began Jaipal had raised a large army of Punjabi Hindus. When Jaipal went to the Punjab region, his army was raised to 100,000 horsemen and an innumerable host of foot soldiers. According to Ferishta:

The two armies having met on the confines of Lumghan, Subooktugeen ascended a hill to view the forces of Jeipal, which appeared in extent like the boundless ocean, and in number like the ants or the locusts of the wilderness. But Subooktugeen considered himself as a wolf about to attack a flock of sheep: calling, therefore, his chiefs together, he encouraged them to glory, and issued to each his commands. His soldiers, though few in number, were divided into squadrons of five hundred men each, which were directed to attack successively, one particular point of the Hindoo line, so that it might continually have to encounter fresh troops.[95]

However, the army was hopeless in battle against the western forces, particularly against the young Mahmud of Ghazni.[95] In the year 1001, soon after Sultan Mahmud came to power and was occupied with the Qarakhanids north of the Hindu Kush, Jaipal attacked Ghazni once more and suffered yet another defeat by the powerful Ghaznavid forces, near present-day Peshawar. After the Battle of Peshawar, he committed suicide because his subjects thought he had brought disaster and disgrace to the Shahi dynasty.[94][95]

Jayapala was succeeded by his son Anandapala,[94] who along with other succeeding generations of the Shahiya dynasty took part in various campaigns against the advancing Ghaznavids but were unsuccessful. The Hindu rulers eventually exiled themselves to the Kashmir Siwalik Hills.[95]

The Gardez Ganesha, representing a Hindu deity, Ganesha, consecrated by the Shahis in Gardez, Afghanistan.

The Gardez Ganesha, representing a Hindu deity, Ganesha, consecrated by the Shahis in Gardez, Afghanistan.

Islamic conquest

In 642 CE, Rashidun Arabs had conquered most of West Asia from the Sassanids and Byzantines, and from the western city of Herat they introduced the religion of Islam as they entered new cities. Afghanistan at that period had a number of different independent rulers, depending on the area. Ancestors of Abū Ḥanīfa, including his father, were from the Kabul region.

The early Arab forces did not fully explore Afghanistan due to attacks by the mountain tribes. Much of the eastern parts of the country remained independent, as part of the Hindu Shahi kingdoms of Kabul and Gandhara, which lasted that way until the forces of the Muslim Saffarid dynasty followed by the Ghaznavids conquered them.

Arab armies carrying the banner of Islam came out of the west to defeat the Sasanians in 642 CE and then they marched with confidence to the east. On the western periphery of the Afghan area the princes of Herat and Seistan gave way to rule by Arab governors but in the east, in the mountains, cities submitted only to rise in revolt and the hastily converted returned to their old beliefs once the armies passed. The harshness and avariciousness of Arab rule produced such unrest, however, that once the waning power of the Caliphate became apparent, native rulers once again established themselves independent. Among these the Saffarids of Seistan shone briefly in the Afghan area. The fanatic founder of this dynasty, the persian Yaqub ibn Layth Saffari, came forth from his capital at Zaranj in 870 CE and marched through Bost, Kandahar, Ghazni, Kabul, Bamyan, Balkh and Herat, conquering in the name of Islam.[97]

— Nancy Hatch Dupree, 1971

Ghaznavids

.PNG.webp)

The Ghaznavid dynasty ruled from the city of Ghazni in eastern Afghanistan. From 997 to his death in 1030, Mahmud of Ghazni turned the former provincial city of Ghazni into the wealthy capital of an extensive empire which covered most of today's Afghanistan, eastern and central Iran, Pakistan, parts of India, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Mahmud of Ghazni (Mahmude Ghaznavi in local pronunciation) consolidated the conquests of his predecessors and the city of Ghazni became a great cultural centre as well as a base for frequent forays into the Indian subcontinent. The Nasher Khans became princes of the Kharoti until the Soviet invasion.[98][99][100]

Ghorids

The Ghaznavid dynasty was defeated in 1148 by the Ghurids from Ghor, but the Ghaznavid Sultans continued to live in Ghazni as the 'Nasher' until the early 20th century.[98][99][100] The empire was established by three brothers from Ghor region of Afghanistan Qutb al-Din, Sayf al-Din, Baha al-Din which all them fought against Ghaznavid emperor Bahram Shah of Ghazni but were not successful and killed in the process. Initially Ala al-Din Husayn, the son of Baha al-Din defeated the Ghazanavid ruler Bahram Shah and to take revenge of his father and uncle's death ordered the city to be sacked. The Ghorids or Ghurids lost the northern territory of Transoxiana and northern Great Korasan especially their capital Ghor province due to the invasion of Seljucks but Sultan Ala al-Din's successors consolidated their power in India by defeating the remainder of Ghaznavid rulers. At their largest extent they ruled east of Iran, much of the Indian subcontinent like Pakistan, and north and central part of modern India.

Mongol invasion

The Mongols invaded Afghanistan in 1221 having defeated the Khwarazmian armies. The Mongols invasion had long-term consequences with many parts of Afghanistan never recovering from the devastation. The towns and villages suffered much more than the nomads who were able to avoid attack. The destruction of irrigation systems maintained by the sedentary people led to the shift of the weight of the country towards the hills. The city of Balkh was destroyed and even 100 years later Ibn Battuta described it as a city still in ruins. While the Mongols were pursuing the forces of Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu they besieged the city of Bamyan. In the course of the siege a defender's arrow killed Genghis Khan's grandson Mutukan. The Mongols razed the city and massacred its inhabitants in revenge, with its former site known as the City of Screams. Herat, located in a fertile valley, was destroyed as well but was rebuilt under the local Kart dynasty. After the Mongol Empire splintered, Herat eventually became part of the Ilkhanate while Balkh and the strip of land from Kabul through Ghazni to Kandahar went to the Chagatai Khanate.[109] The Afghan tribal areas south of the Hindu Kush were usually either allied with the Khalji dynasty of northern India or independent.

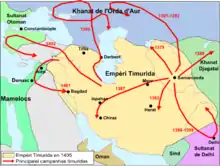

Timurids

Timur (Tamerlane) incorporated much of the area into his own vast Timurid Empire. The city of Herat became one of the capitals of his empire, and his grandson Pir Muhammad held the seat of Kandahar. Timur rebuilt most of Afghanistan's infrastructure which was destroyed by his early ancestor. The area was progressing under his rule. Timurid rule began declining in the early 16th century with the rise of a new ruler in Kabul, Babur. Timur, a descendant of Genghis Khan, created a vast new empire across Russia and Persia which he ruled from his capital in Samarkand in present-day Uzbekistan. Timur captured Herat in 1381 and his son, Shah Rukh moved the capital of the Timurid empire to Herat in 1405. The Timurids, a Turkic people, brought the Turkic nomadic culture of Central Asia within the orbit of Persian civilisation, establishing Herat as one of the most cultured and refined cities in the world. This fusion of Central Asian and Persian culture was a major legacy for the future Afghanistan. Under the rule of Shah Rukh the city served as the focal point of the Timurid Renaissance, whose glory matched Florence of the Italian Renaissance as the center of a cultural rebirth.[110][111] A century later, the emperor Babur, a descendant of Timur, visited Herat and wrote, "the whole habitable world had not such a town as Herat." For the next 300 years the eastern Afghan tribes periodically invaded India creating vast Indo-Afghan empires. In 1500 CE, Babur was driven out of his home in the Ferghana valley. By the 16th century western Afghanistan again reverted to Persian rule under the Safavid dynasty.[112][113]

Modern era (1504–1973)

Mughals, Uzbeks, and Safavids

In 1504, Babur, a descendant of Timur, arrived from present-day Uzbekistan and moved to the city of Kabul. He began exploring new territories in the region, with Kabul serving as his military headquarters. Instead of looking towards the powerful Safavids towards the Persian west, Babur was more focused on the Indian subcontinent. In 1526, he left with his army to capture the seat of the Delhi Sultanate, which at that point was possessed by the Afghan Lodi dynasty of India. After defeating Ibrahim Lodi and his army, Babur turned (Old) Delhi into the capital of his newly established Mughal Empire.

From the 16th century to the 17th century CE, Afghanistan was divided into three major areas. The north was ruled by the Khanate of Bukhara, the west was under the rule of the Iranian Shia Safavids, and the eastern section was under the Sunni Mughals of northern India, who under Akbar established in Kabul one of the original twelve subahs (imperial top-level provinces), bordering Lahore, Multan and Kashmir (added to Kabul in 1596, later split-off) and short-lived Balkh Subah and Badakhshan Subah (only 1646–47). The Kandahar region in the south served as a buffer zone between the Mughals (who shortly established a Qandahar subah 1638–1648) and Persia's Safavids, with the native Afghans often switching support from one side to the other. Babur explored a number of cities in the region before his campaign into India. In the city of Kandahar, his personal epigraphy can be found in the Chilzina rock mountain. Like in the rest of the territories that used to make part of the Indian Mughal Empire, Afghanistan holds tombs, palaces, and forts built by the Mughals.[114]

Hotak dynasty

In 1704, the Safavid Shah Husayn appointed George XI (Gurgīn Khān), a ruthless Georgian subject, to govern their easternmost territories in the Greater Kandahar region. One of Gurgīn's main objectives was to crush the rebellions started by native Afghans. Under his rule the revolts were successfully suppressed and he ruled Kandahar with uncompromising severity. He began imprisoning and executing the native Afghans, especially those suspected in having taken part in the rebellions. One of those arrested and imprisoned was Mirwais Hotak who belonged to an influential family in Kandahar. Mirwais was sent as a prisoner to the Persian court in Isfahan, but the charges against him were dismissed by the king, so he was sent back to his native land as a free man.[115]

In April 1709, Mirwais along with his militia under Saydal Khan Naseri revolted.[116][117] The uprising began when George XI and his escort were killed after a banquet that had been prepared by Mirwais at his house outside the city.[118] Around four days later, an army of well-trained Georgian troops arrived in the city after hearing of Gurgīn's death, but Mirwais and his Afghan forces successfully held the city against the troops. Between 1710 and 1713, the Afghan forces defeated several large Persian armies that were dispatched from Isfahan by the Safavids, which included Qizilbash and Georgian/Circassian troops.[119]

Several half-hearted attempts to subdue the rebellious city having failed, the Persian Government despatched Khusraw Khán, nephew of the late Gurgín Khán, with an army of 30,000 men to effect its subjugation, but in spite of an initial success, which led the Afghans to offer to surrender on terms, his uncompromising attitude impelled them to make a fresh desperate effort, resulting in the complete defeat of the Persian army (of whom only some 700 escaped) and the death of their general. Two years later, in 1713, another Persian army commanded by Rustam Khán was also defeated by the rebels, who thus secured possession of the whole province of Qandahár.[120]

— Edward G. Browne, 1924

Southern Afghanistan was made into an independent local Pashtun kingdom.[121] Refusing the title of king, Mirwais was called "Prince of Qandahár and general of the national troops" by his Afghan countrymen. He died of natural causes in November 1715 and was succeeded by his brother Abdul Aziz Hotak. Aziz was killed about two years later by Mirwais' son Mahmud Hotaki, allegedly for planning to give Kandahar's sovereignty back to Persia.[122] Mahmud led an Afghan army into Persia in 1722 and defeated the Safavids at the Battle of Gulnabad. The Afghans captured Isfahan (Safavid capital) and Mahmud briefly became the new Persian Shah. He was known after that as Shah Mahmud.

Mahmud began a short-lived reign of terror against his Persian subjects who defied his rule from the very start, and he was eventually murdered in 1725 by his own cousin, Shah Ashraf Hotaki. Some sources say he died of madness . Ashraf became the new Afghan Shah of Persia soon after Mahmud's death, while the home region of Afghanistan was ruled by Mahmud's younger brother Shah Hussain Hotaki. Ashraf was able to secure peace with the Ottoman Empire in 1727 (See Treaty of Hamedan), winning against a superior Ottoman army during the Ottoman-Hotaki War, but the Russian Empire took advantage of the continuing political unrest and civil strife to seize former Persian territories for themselves, limiting the amount of territory under Shah Mahmud's control.

The short lived Hotaki dynasty was a troubled and violent one from the very start as internecine conflict made it difficult for them to establish permanent control. The dynasty lived under great turmoil due to bloody succession feuds that made their hold on power tenuous. There was a massacre of thousands of civilians in Isfahan; including more than three thousand religious scholars, nobles, and members of the Safavid family.[123] The vast majority of the Persians rejected the Afghan regime which they considered to have been usurping power from the very start. Hotaki's rule continued in Afghanistan until 1738 when Shah Hussain was defeated and banished by Nader Shah of Persia.[124]

The Hotakis were eventually removed from power in 1729, after a very short lived reign. They were defeated in the October 1729 by the Iranian military commander Nader Shah, head of the Afsharids, at the Battle of Damghan. After several military campaigns against the Afghans, he effectively reduced the Hotaki's power to only southern Afghanistan. The last ruler of the Hotaki dynasty, Shah Hussain, ruled southern Afghanistan until 1738 when the Afsharids and the Abdali Pashtuns defeated him at the long Siege of Kandahar.[124]

Afsharid Invasion and Durrani Empire

Nader Shah and his Afsharid army arrived in the town of Kandahar in 1738 and defeated Hussain Hotaki subsequently absorbing all of Afghanistan in his empire and renaming Kandahar as Naderabad. Around this time, a young teenager Ahmad Shah joined Nader Shah's army for his invasion of India.

Nadir Shah was assassinated on 19 June 1747 by several of his Persian officers, and the Afsharid empire fell to pieces. At the same time the 25-year-old Ahmad Khan was busy in Afghanistan calling for a loya jirga ("grand assembly") to select a leader among his people. The Afghans gathered near Kandahar in October 1747 and chose Ahmad Shah from among the challengers, making him their new head of state. After the inauguration or coronation, he became known as Ahmad Shah Durrani. He adopted the title padshah durr-i dawran ('King, "pearl of the age") and the Abdali tribe became known as the Durrani tribe after this.[125] Ahmad Shah not only represented the Durranis but he also united all the Pashtun tribes. By 1751, Ahmad Shah Durrani and his Afghan army conquered the entire present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and for a short time, subjugated large swathes of the Khorasan and Kohistan provinces of Iran, along with Delhi in India.[126] He defeated the Maratha Empire in 1761 at the Battle of Panipat.

In October 1772, Ahmad Shah retired to his home in Kandahar where he died peacefully and was buried at a site that is now adjacent to the Shrine of the Cloak. He was succeeded by his son, Timur Shah Durrani, who transferred the capital of their Afghan Empire from Kandahar to Kabul. Timur died in 1793 and his son Zaman Shah Durrani took over the reign.

Zaman Shah and his brothers had a weak hold on the legacy left to them by their famous ancestor. They sorted out their differences through a "round robin of expulsions, blindings and executions," which resulted in the deterioration of the Afghan hold over far-flung territories, such as Attock and Kashmir. Durrani's other grandson, Shuja Shah Durrani, fled the wrath of his brother and sought refuge with the Sikhs. Not only had Durrani invaded the Punjab region many times, but had destroyed the holiest shrine of the Sikhs – the Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar, defiling its sarowar with the blood of cows and decapitating Baba Deep Singh in 1757. The Sikhs, under Ranjit Singh, eventually wrested a large part of the Durrani Kingdom (present day Pakistan, but not including Sindh) from the Afghans while they were in civil war.[127]

Barakzai dynasty and British influence

The Emir Dost Mohammed Khan (1793–1863) gained control in Kabul in 1826 after toppling his brother, Sultan Mohammad Khan, and founded (c. 1837) the Barakzai dynasty. In 1837, the Afghan army descended through the Khyber Pass on Sikh forces at Jamrud killed the Sikh general Hari Singh Nalwa but could not capture the fort.[128] Rivalry between the expanding British and Russian Empires in what became known as "The Great Game" significantly influenced Afghanistan during the 19th century. British concern over Russian advances in Central Asia and over Russia's growing influence in West Asia and in Persia in particular culminated in two Anglo-Afghan wars and in the Siege of Herat (1837–1838), in which the Persians, trying to retake Afghanistan and throw out the British, sent armies into the country and fought the British mostly around and in the city of Herat. The first Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842) resulted in the destruction of a British army; causing great panic throughout British India and the dispatch of a second British invasion army.[129] Following the British defeat in the First Anglo-Afghan War, where they tried to re-establish the Durrani Kingdom as a de facto vassal, Dost Mohammad could focus on reuniting Afghanistan, which was divided following the Durrani-Barakzai civil wars. Dost Mohammad began his conquest while only ruling the major cities of Kabul, Ghazni, Jalalabad, and Bamyan. By the time of his death in 1863, Dost Mohammad had reunited most of Afghanistan. Following Dost Mohammad's death, a civil war broke out amongst his sons, leading to Sher Ali succeeding and beginning his rule. The Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880) resulted from the refusal by Emir Shir Ali (reigned 1863 to 1866 and from 1868 to 1879) to accept a British diplomatic mission in Kabul. In the wake of this conflict Shir Ali's nephew, Emir Abdur Rahman, known as "Iron Emir",[130] came to the Afghan throne. During his reign (1880–1901), the British and Russians officially established the boundaries of what would become modern Afghanistan. The British retained effective control over Kabul's foreign affairs. Abdur Rahman's reforms of the army, legal system and structure of government gave Afghanistan a degree of unity and stability which it had not before known. This, however, came at the cost of strong centralisation, of harsh punishments for crime and corruption, and of a certain degree of international isolation.[131]

Habibullah Khan, Abdur Rahman's son, came to the throne in 1901 and kept Afghanistan neutral during World War I, despite encouragement by Central Powers of anti-British feelings and of Afghan rebellion along the borders of India. His policy of neutrality was not universally popular within the country, and Habibullah was assassinated in 1919, possibly by family members opposed to British influence. His third son, Amanullah (r. 1919–1929), regained control of Afghanistan's foreign policy after launching the Third Anglo-Afghan War (May to August 1919) with an attack on India. During the ensuing conflict the war-weary British relinquished their control over Afghan foreign affairs by signing the Treaty of Rawalpindi in August 1919. In commemoration of this event Afghans celebrate 19 August as their Independence Day.

Reforms of Amanullah Khan and civil war

_with_his_followers.jpg.webp)

King Amanullah Khan moved to end his country's traditional isolation in the years following the Third Anglo-Afghan war. After quelling the Khost rebellion in 1925, he established diplomatic relations with most major countries and, following a 1927 tour of Europe and Turkey (during which he noted the modernization and secularization advanced by Atatürk), introduced several reforms intended to modernize Afghanistan. A key force behind these reforms was Mahmud Tarzi, Amanullah Khan's Foreign Minister and father-in-law — and an ardent supporter of the education of women. He fought for Article 68 of Afghanistan's first constitution (declared through a Loya Jirga), which made elementary education compulsory.[132] Some of the reforms that were actually put in place, such as the abolition of the traditional Muslim veil for women and the opening of a number of co-educational schools, quickly alienated many tribal and religious leaders, which led to the revolt of the Shinwari in November 1928, marking the beginning of the Afghan Civil War (1928–1929). Although the Shinwari revolt was quelled, a concurrent Saqqawist uprising in the north eventually managed to depose Amanullah, leading to Habibullāh Kalakāni taking control of Kabul.[133]

Reigns of Nadir Khan and Zahir Khan

Mohammed Nadir Khan became King of Afghanistan on 15 October 1929 after he took control of Afghanistan by defeating the Habibullah Kalakani. He then executed him in 1 November of same year.[134] He began consolidating power and regenerating the country. He abandoned the reforms of Amanullah Khan in favour of a more gradual approach to modernisation. In 1933, however, he was assassinated in a revenge killing by a student from Kabul.

Mohammad Zahir Shah, Nadir Khan's 19-year-old son, succeeded to the throne and reigned from 1933 to 1973. The Afghan tribal revolts of 1944–1947 saw Zahir Shah's reign being challenged by Zadran, Safi and Mangal tribesmen led by Mazrak Zadran and Salemai among others. Until 1946 Zahir Shah ruled with the assistance of his uncle Sardar Mohammad Hashim Khan, who held the post of Prime Minister and continued the policies of Nadir Khan. In 1946, another of Zahir Shah's uncles, Sardar Shah Mahmud Khan, became Prime Minister and began an experiment allowing greater political freedom, but reversed the policy when it went further than he expected. In 1953, he was replaced as Prime Minister by Mohammed Daoud Khan, the king's cousin and brother-in-law. Daoud looked for a closer relationship with the Soviet Union and a more distant one towards Pakistan. However, disputes with Pakistan led to an economic crisis and he was asked to resign in 1963. From 1963 until 1973, Zahir Shah took a more active role.

In 1964, King Zahir Shah promulgated a liberal constitution providing for a bicameral legislature to which the king appointed one-third of the deputies. The people elected another third, and the remainder were selected indirectly by provincial assemblies. Although Zahir's "experiment in democracy" produced few lasting reforms, it permitted the growth of parties on both the left and the right. This included the communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), which had close ideological ties to the Soviet Union. In 1967, the PDPA split into two major rival factions: the Khalq (Masses) was headed by Nur Muhammad Taraki and Hafizullah Amin who were supported by elements within the military, and the Parcham (Banner) led by Babrak Karmal.

Contemporary era (1973–present)

Republic of Afghanistan and the end of the monarchy

Amid corruption charges and malfeasance against the royal family and the poor economic conditions created by the severe 1971–72 drought, former Prime Minister Mohammad Sardar Daoud Khan seized power in a non-violent coup on July 17, 1973, while Zahir Shah was receiving treatment for eye problems and therapy for lumbago in Italy.[135] Daoud abolished the monarchy, abrogated the 1964 constitution, and declared Afghanistan a republic with himself as its first President and Prime Minister. His attempts to carry out badly needed economic and social reforms met with little success, and the new constitution promulgated in February 1977 failed to quell chronic political instability.

As disillusionment set in, in 1978 a prominent member of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), Mir Akbar Khyber (or "Kaibar"), was killed by the government. The leaders of PDPA apparently feared that Daoud was planning to exterminate them all, especially since most of them were arrested by the government shortly after. Nonetheless, Hafizullah Amin and a number of military wing officers of the PDPA's Khalq faction managed to remain at large and organize a military coup.

Democratic Republic and Soviet war (1978–1989)

.jpg.webp)

On 28 April 1978, the PDPA, led by Nur Mohammad Taraki, Babrak Karmal and Amin Taha overthrew the government of Mohammad Daoud, who was assassinated along with all his family members in a bloody military coup. The coup became known as the Saur Revolution. On 1 May, Taraki became head of state, head of government and General Secretary of the PDPA. The country was then renamed the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA), and the PDPA regime lasted, in some form or another, until April 1992.

In March 1979, Hafizullah Amin took over as prime minister, retaining the position of field marshal and becoming vice-president of the Supreme Defence Council. Taraki remained General Secretary, Chairman of the Revolutionary Council and in control of the Army. On 14 September, Amin overthrew Taraki, who was killed. Amin stated that "the Afghans recognize only crude force."[136] Afghanistan expert Amin Saikal writes: "As his powers grew, so apparently did his craving for personal dictatorship ... and his vision of the revolutionary process based on terror."[136]

Once it was in power, the PDPA implemented a Marxist–Leninist agenda. It moved to replace religious and traditional laws with secular and Marxist–Leninist ones. Men were obliged to cut their beards, women could not wear chadors, and mosques were declared off limits. The PDPA made a number of reforms on women's rights, banning forced marriages and giving state recognition of women's right to vote. A prominent example was Anahita Ratebzad, who was a major Marxist leader and a member of the Revolutionary Council. Ratebzad wrote the famous New Kabul Times editorial (May 28, 1978) which declared: "Privileges which women, by right, must have are equal education, job security, health services, and free time to rear a healthy generation for building the future of the country ... Educating and enlightening women is now the subject of close government attention." The PDPA also carried out socialist land reforms and moved to promote state atheism.[137] They also prohibited usury.[138] The PDPA invited the Soviet Union to assist in modernizing its economic infrastructure (predominantly its exploration and mining of rare minerals and natural gas). The Soviet Union also sent contractors to build roads, hospitals and schools and to drill water wells; they also trained and equipped the Afghan Armed Forces. Upon the PDPA's ascension to power, and the establishment of the DRA, the Soviet Union promised monetary aid amounting to at least $1.262 billion.

At the same time, the PDPA imprisoned, tortured or murdered thousands of members of the traditional elite, the religious establishment, and the intelligentsia.[139] The government launched a campaign of violent repression, killing some 10,000 to 27,000 people and imprisoning 14,000 to 20,000 more, mostly at Pul-e-Charkhi prison.[140][141][142] In December 1978 the PDPA leadership signed an agreement with the Soviet Union which would allow military support for the PDPA in Afghanistan if needed. The majority of people in the cities including Kabul either welcomed or were ambivalent to these policies. However, the Marxist–Leninist and secular nature of the government as well as its heavy dependence on the Soviet Union made it unpopular with a majority of the Afghan population. Repressions plunged large parts of the country, especially the rural areas, into open revolt against the new Marxist–Leninist government. By spring 1979 unrests had reached 24 out of 28 Afghan provinces including major urban areas. Over half of the Afghan army would either desert or join the insurrection. Most of the government's new policies clashed directly with the traditional Afghan understanding of Islam, making religion one of the only forces capable of unifying the tribally and ethnically divided population against the unpopular new government, and ushering in the advent of Islamist participation in Afghan politics.[143]

To bolster the Parcham faction, the Soviet Union decided to intervene on December 27, 1979, when the Red Army invaded its southern neighbor. Over 100,000 Soviet troops took part in the invasion, which was backed by another 100,000 Afghan military men and supporters of the Parcham faction. In the meantime, Hafizullah Amin was killed and replaced by Babrak Karmal.

The Carter administration started providing limited assistance to rebels before the Soviet invasion. After the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, the U.S. began arming the Afghan mujahideen, thanks in large part to the efforts of Charlie Wilson and CIA officer Gust Avrakotos. Early reports estimated that $6–20 billion had been spent by the U.S. and Saudi Arabia[144] but more recent reports state that the U.S. and Saudi Arabia provided as much as up to $40 billion[145][146][147] in cash and weapons, which included over two thousand FIM-92 Stinger surface-to-air missiles, for building up Islamic groups against the Soviet Union. The U.S. handled most of its support through Pakistan's ISI.

Scholars such as W. Michael Reisman,[148] Charles Norchi[149] and Mohammed Kakar, believe that the Afghans were victims of a genocide which was committed against them by the Soviet Union.[150][151] Soviet forces and their proxies killed between 562,000[152] and 2 million Afghans[153][154] and Russian soldiers also engaged in abductions and rapes of Afghan women.[155][156] About 6 million fled as Afghan refugees to Pakistan and Iran, and from there over 38,000 made it to the United States[157] and many more to the European Union. The Afghan refugees in Iran and Pakistan brought with them verifiable stories of murder, collective rape, torture and depopulation of civilians by the Soviet forces.[158] Faced with mounting international pressure and great number of casualties on both sides, the Soviets withdrew in 1989. Their withdrawal from Afghanistan was seen as an ideological victory in the United States, which had backed some Mujahideen factions through three U.S. presidential administrations to counter Soviet influence in the vicinity of the oil-rich Persian Gulf. The USSR continued to support Afghan leader Mohammad Najibullah (former head of the Afghan secret service, KHAD) until 1992.[159]

Foreign interference and civil war (1989–1996)

Pakistan's spy agency Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), headed by Hamid Gul at the time, was interested in a trans-national Islamic revolution which would cover Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia. For this purpose the ISI masterminded an attack on Jalalabad in March 1989, for the Mujahideen to establish their own government in Afghanistan, but this failed in three months.[160]

With the crumbling of the Najibullah regime early in 1992, Afghanistan fell into further disarray and civil war. A U.N.-supported attempt to have the mujahideen parties and armies form a coalition government shattered. Mujahideen did not abide by the mutual pledges and Ahmad Shah Masood forces because of his proximity to Kabul captured the capital before Mujahideen Govt was established. So the elected prime minister and warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, started war on his president and Massod force entrenched in Kabul. This ignited civil war, because the other mujahideen parties would not settle for Hekmatyar ruling alone or sharing actual power with him. Within weeks, the still frail unity of the other mujahideen forces also evaporated, and six militias were fighting each other in and around Kabul.

Sibghatuallah Mojaddedi was elected as Afghanistan's elected interim president for two months and then professor Burhanuddin Rabbani a well known Kabul university professor and the leader of Jamiat-e-Islami party of Mujahiddin who fought against Russians during the occupation was chosen by all of the Jahadi leaders except Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Rabbani reigned as the official and elected president of Afghanistan by Shurai Mujahiddin Peshawer (Peshawer Mujahiddin Council) from 1992 until 2001 when he officially handed over the presidency post to Hamid Karzai the next US appointed interim president. During Rabbani's presidency some parts of the country including a few provinces in the north such as Mazar e-Sharif, Jawzjan, Faryab, Shuburghan and some parts of Baghlan provinces were ruled by general Abdul Rashid Dostum. During Rabbani's first five years illegal term before the emergence of the Taliban, the eastern and western provinces and some of the northern provinces such as Badakhshan, Takhar, Kunduz, the main parts of Baghlan Province, and some parts of Kandahar and other southern provinces were under the control of the central government while the other parts of southern provinces did not obey him because of his Tajik ethnicity. During the 9 year presidency of Burhanuddin Rabani, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar was directed, funded and supplied by the Pakistani army.[161] Afghanistan analyst Amin Saikal concludes in his book Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival:

Pakistan was keen to gear up for a breakthrough in Central Asia. [...] Islamabad could not possibly expect the new Islamic government leaders [...] to subordinate their own nationalist objectives in order to help Pakistan realize its regional ambitions. [...] Had it not been for the ISI's logistic support and supply of a large number of rockets, Hekmatyar's forces would not have been able to target and destroy half of Kabul.[162]

There was no time for the interim government to create working government departments, police units or a system of justice and accountability. Saudi Arabia and Iran also armed and directed Afghan militias.[136] A publication by the George Washington University describes:

[O]utside forces saw instability in Afghanistan as an opportunity to press their own security and political agendas.[163]

According to Human Rights Watch, numerous Iranian agents were assisting the Shia Hezb-i Wahdat forces of Abdul Ali Mazari, as Iran was attempting to maximize Wahdat's military power and influence.[136][164][165] Saudi Arabia was trying to strengthen the Wahhabite Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and his Ittihad-i Islami faction.[136][164] Atrocities were committed by individuals of the different factions while Kabul descended into lawlessness and chaos as described in reports by Human Rights Watch and the Afghanistan Justice Project.[164][166] Again, Human Rights Watch writes:

Rare ceasefires, usually negotiated by representatives of Ahmad Shah Massoud, Sibghatullah Mojaddedi or Burhanuddin Rabbani (the interim government), or officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), commonly collapsed within days.[164]

The main forces involved during that period in Kabul, northern, central and eastern Afghanistan were the Hezb-i Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar directed by Pakistan, the Hezb-i Wahdat of Abdul Ali Mazari directed by Iran, the Ittehad-i Islami of Abdul Rasul Sayyaf supported by Saudi Arabia, the Junbish-i Milli of Abdul Rashid Dostum backed by Uzbekisten, the Harakat-i Islami of Hussain Anwari and the Shura-i Nazar operating as the regular Islamic State forces (as agreed upon in the Peshawar Accords) under the Defence Ministry of Ahmad Shah Massoud.

Meanwhile, the southern city of Kandahar was a centre of lawlessness, crime and atrocities fuelled by complex Pashtun tribal rivalries.[167] In 1994, the Taliban (a movement originating from Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-run religious schools for Afghan refugees in Pakistan) also developed in Afghanistan as a politico-religious force, reportedly in opposition to the tyranny of the local governor.[167] Mullah Omar started his movement with fewer than 50 armed madrassah students in his hometown of Kandahar.[167] As Gulbuddin Hekmatyar remained unsuccessful in conquering Kabul, Pakistan started supporting the Taliban.[136][168] Many analysts like Amin Saikal describe the Taliban as developing into a proxy force for Pakistan's regional interests.[136] In 1994 the Taliban took power in several provinces in southern and central Afghanistan.

In 1995 the Hezb-i Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the Iranian-backed Hezb-i Wahdat as well as Rashid Dostum's Junbish forces were defeated militarily in the capital Kabul by forces of the interim government under Massoud who subsequently tried to initiate a nationwide political process with the goal of national consolidation and democratic elections, also inviting the Taliban to join the process.[169] The Taliban declined.[169]

Taliban and the United Front (1996–2001)

.PNG.webp)

The Taliban started shelling Kabul in early 1995 but were defeated by forces of the Islamic State government under Ahmad Shah Massoud.[170] Amnesty International, referring to the Taliban offensive, wrote in a 1995 report:

This is the first time in several months that Kabul civilians have become the targets of rocket attacks and shelling aimed at residential areas in the city.[170]

On September 26, 1996, as the Taliban, with military support by Pakistan and financial support by Saudi Arabia, prepared for another major offensive, Massoud ordered a full retreat from Kabul.[171] The Taliban seized Kabul on September 27, 1996, and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. They imposed on the parts of Afghanistan under their control their political and judicial interpretation of Islam, issuing edicts forbidding women from working outside the home, attending school or leaving their homes unless accompanied by a male relative.[172] Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) said:

To PHR's knowledge, no other regime in the world has methodically and violently forced half of its population into virtual house arrest, prohibiting them on pain of physical punishment.[172]

After the fall of Kabul to the Taliban on September 27, 1996,[173] Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rashid Dostum, two former enemies, created the United Front (Northern Alliance) against the Taliban, who were preparing offensives against the remaining areas under the control of Massoud and Dostum.[174] The United Front included beside the dominantly Tajik forces of Massoud and the Uzbek forces of Dostum, Hazara factions and Pashtun forces under the leadership of commanders such as Abdul Haq, Haji Abdul Qadir, Qari Baba or diplomat Abdul Rahim Ghafoorzai. From the Taliban conquest in 1996 until November 2001 the United Front controlled roughly 30% of Afghanistan's population in provinces such as Badakhshan, Kapisa, Takhar and parts of Parwan, Kunar, Nuristan, Laghman, Samangan, Kunduz, Ghōr and Bamyan.

According to a 55-page report by the United Nations, the Taliban, while trying to consolidate control over northern and western Afghanistan, committed systematic massacres against civilians.[175][176] UN officials stated that there had been "15 massacres" between 1996 and 2001.[175][176] They also said, that "[t]hese have been highly systematic and they all lead back to the [Taliban] Ministry of Defense or to Mullah Omar himself."[175][176] The Taliban especially targeted people of Shia religious or Hazara ethnic background.[175][176] Upon taking Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998, about 4,000 civilians were executed by the Taliban and many more reported torture.[177][178] Among those killed in Mazari Sharif were several Iranian diplomats. Others were kidnapped by the Taliban, touching off a hostage crisis that nearly escalated to a full-scale war, with 150,000 Iranian soldiers massed on the Afghan border at one time.[179] It was later admitted that the diplomats were killed by the Taliban, and their bodies were returned to Iran.[180]

The documents also reveal the role of Arab and Pakistani support troops in these killings.[175][176] Osama bin Laden's so-called 055 Brigade was responsible for mass-killings of Afghan civilians.[181] The report by the United Nations quotes eyewitnesses in many villages describing Arab fighters carrying long knives used for slitting throats and skinning people.[175][176]

Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf – then as Chief of Army Staff – was responsible for sending thousands of Pakistanis to fight alongside the Taliban and Bin Laden against the forces of Massoud.[168][169][182][183] In total there were believed to be 28,000 Pakistani nationals fighting inside Afghanistan.[169] 20,000 were regular Pakistani soldiers either from the Frontier Corps or army and an estimated 8,000 were militants recruited in madrassas filling regular Taliban ranks.[181] The estimated 25,000 Taliban regular force thus comprised more than 8,000 Pakistani nationals.[181] A 1998 document by the U.S. State Department confirms that "20–40 percent of [regular] Taliban soldiers are Pakistani."[168] The document further states that the parents of those Pakistani nationals "know nothing regarding their child's military involvement with the Taliban until their bodies are brought back to Pakistan."[168] A further 3,000 fighter of the regular Taliban army were Arab and Central Asian militants.[181] From 1996 to 2001 the Al Qaeda of Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri became a state within the Taliban state.[184] Bin Laden sent Arab recruits to join the fight against the United Front.[184][185] Of roughly 45,000 Pakistani, Taliban and Al Qaeda soldiers fighting against the forces of Massoud only 14,000 were Afghan.[169][181]

According to Human Rights Watch in 1997 Taliban soldiers were summarily executed in and around Mazar-i Sharif by Dostum's Junbish forces.[186] Dostum was defeated by the Taliban in 1998 with the fall of Mazar-i-Sharif. Massoud remained the only leader of the United Front in Afghanistan.

In the areas under his control Ahmad Shah Massoud set up democratic institutions and signed the Women's Rights Charter.[187] Human Rights Watch cites no human rights crimes for the forces under direct control of Massoud for the period from October 1996 until the assassination of Massoud in September 2001.[186] As a consequence many civilians fled to the area of Ahmad Shah Massoud.[182][188] National Geographic concluded in its documentary Inside the Taliban:

The only thing standing in the way of future Taliban massacres is Ahmad Shah Massoud.[182]

The Taliban repeatedly offered Massoud a position of power to make him stop his resistance. Massoud declined for he did not fight to obtain a position of power. He said in one interview:

The Taliban say: "Come and accept the post of prime minister and be with us", and they would keep the highest office in the country, the presidentship. But for what price?! The difference between us concerns mainly our way of thinking about the very principles of the society and the state. We can not accept their conditions of compromise, or else we would have to give up the principles of modern democracy. We are fundamentally against the system called "the Emirate of Afghanistan".[189]

and

There should be an Afghanistan where every Afghan finds himself or herself happy. And I think that can only be assured by democracy based on consensus.[190]

Massoud wanted to convince the Taliban to join a political process leading towards democratic elections in a foreseeable future.[189] Massoud stated that:

The Taliban are not a force to be considered invincible. They are distanced from the people now. They are weaker than in the past. There is only the assistance given by Pakistan, Osama bin Laden and other extremist groups that keep the Taliban on their feet. With a halt to that assistance, it is extremely difficult to survive.[190]

In early 2001 Massoud employed a new strategy of local military pressure and global political appeals.[191] Resentment was increasingly gathering against Taliban rule from the bottom of Afghan society including the Pashtun areas.[191] Massoud publicized their cause "popular consensus, general elections and democracy" worldwide. At the same time he was very wary not to revive the failed Kabul government of the early 1990s.[191] Already in 1999 he started the training of police forces which he trained specifically to keep order and protect the civilian population in case the United Front would be successful.[169]

In early 2001 Massoud addressed the European Parliament in Brussels asking the international community to provide humanitarian help to the people of Afghanistan.[192] He stated that the Taliban and Al Qaeda had introduced "a very wrong perception of Islam" and that without the support of Pakistan the Taliban would not be able to sustain their military campaign for up to a year.[192]

NATO's presence, the Emergency Loya Jirga, the Taliban's takeover and the Panjshir uprising

On 9 September 2001, Ahmad Shah Massoud was assassinated by two Arab suicide attackers inside Afghanistan. Two days later about 3,000 people became victims of the September 11 attacks in the United States, when Afghan-based Al-Qaeda suicide bombers hijacked planes and flew them into four targets in the Northeastern United States. Then US President George W. Bush accused Osama bin Laden and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed as the faces behind the attacks. When the Taliban refused to hand over bin Laden to US authorities and to disband al-Qaeda bases in Afghanistan, Operation Enduring Freedom was launched in which teams of American and British special forces worked with commanders of the United Front (Northern Alliance) against the Taliban.[193] At the same time the US-led forces were bombing Taliban and al-Qaeda targets everywhere inside Afghanistan with cruise missiles. These actions led to the fall of Mazar-i-Sharif in the north followed by all the other cities, as the Taliban and al-Qaeda crossed over the porous Durand Line border into Pakistan. In December 2001, after the Taliban government was toppled and the new Afghan government under Hamid Karzai was formed, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was established by the UN Security Council to help assist the Karzai administration and provide basic security to the Afghan people.[194][195] The majority of Afghans supported the American invasion of their country.[196][197]

While the Taliban began regrouping inside Pakistan, the rebuilding of war-torn Afghanistan kicked off in 2002 (see also War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)).[198][199] The Afghan nation was able to build democratic structures over the years by the creation of an emergency loya jirga to set up the modern Afghan government, and some progress was made in key areas such as governance, economy, health, education, transport, and agriculture. NATO had been training the Afghan armed forces as well its national police. ISAF and Afghan troops led many offensives against the Taliban but failed to fully defeat them. By 2009, a Taliban-led shadow government began to form in many parts of the country complete with their own version of mediation court.[200] After U.S. President Barack Obama announced the deployment of another 30,000 soldiers in 2010 for a period of two years, Der Spiegel published images of the US soldiers who killed unarmed Afghan civilians.[201]

In 2009, the United States resettled 328 refugees from Afghanistan.[202] Over five million Afghan refugees were repatriated in the last decade, including many who were forcefully deported from NATO countries.[203][204] This large return of Afghans may have helped the nation's economy but the country still remains one of the poorest in the world due to the decades of war, lack of foreign investment, ongoing government corruption and the Pakistani-backed Taliban insurgency.[205][206] The United States also accuses neighboring Iran of providing small level of support to the Taliban insurgents.[207][208][209] According to a report by the United Nations, the Taliban and other militants were responsible for 76% of civilian casualties in 2009,[210] 75% in 2010[211] and 80% in 2011.[212]

In October 2008 U.S. Defense Secretary Gates had asserted that a political settlement with the Taliban was the endgame for the Afghanistan war. "There has to be ultimately – and I'll underscore ultimately – reconciliation as part of a political outcome to this," Gates stated.[213] By 2010 peace efforts began. In early January, Taliban commanders held secret exploratory talks with a United Nations special envoy to discuss peace terms. Regional commanders on the Taliban's leadership council, the Quetta Shura, sought a meeting with the UN special representative in Afghanistan, Kai Eide, and it took place in Dubai on January 8. It was the first such meeting between the UN and senior members of the Taliban.[214] On 26 January 2010, at a major conference in London which brought together some 70 countries and organizations,[215] Afghan President Hamid Karzai said he intends to reach out to the Taliban leadership (including Mullah Omar, Sirajuddin Haqqani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar). Supported by NATO, Karzai called on the group's leadership to take part in a loya jirga meeting to initiate peace talks. These steps have resulted in an intensification of bombings, assassinations and ambushes.[216] Some Afghan groups (including the former intelligence chief Amrullah Saleh and opposition leader Dr. Abdullah Abdullah) believe that Karzai plans to appease the insurgents' senior leadership at the cost of the democratic constitution, the democratic process and progress in the field of human rights especially women's rights.[217] Dr. Abdullah stated:

I should say that Taliban are not fighting in order to be accommodated. They are fighting in order to bring the state down. So it's a futile exercise, and it's just misleading. ... There are groups that will fight to the death. Whether we like to talk to them or we don't like to talk to them, they will continue to fight. So, for them, I don't think that we have a way forward with talks or negotiations or contacts or anything as such. Then we have to be prepared to tackle and deal with them militarily. In terms of the Taliban on the ground, there are lots of possibilities and opportunities that with the help of the people in different parts of the country, we can attract them to the peace process; provided, we create a favorable environment on this side of the line. At the moment, the people are leaving support for the government because of corruption. So that expectation is also not realistic at this stage.[218]

Afghan President Hamid Karzai told world leaders during the London conference that he intends to reach out to the top echelons of the Taliban within a few weeks with a peace initiative.[219] Karzai set the framework for dialogue with Taliban leaders when he called on the group's leadership to take part in a "loya jirga" – or large assembly of elders – to initiate peace talks.[220] Karzai also asked for creation of a new peacemaking organization, to be called the National Council for Peace, Reconciliation and Reintegration.[219] Karzai's top adviser on the reconciliation process with the insurgents said that the country must learn to forgive the Taliban.[221] In March 2010, the Karzai government held preliminary talks with Hezb-i-Islami, who presented a plan which included the withdrawal of all foreign troops by the end of 2010. The Taliban declined to participate, saying "The Islamic Emirate has a clear position. We have said this many, many times. There will be no talks when there are foreign troops on Afghanistan's soil killing innocent Afghans on daily basis."[222] In June 2010 the Afghan Peace Jirga 2010 took place. In September 2010 General David Petraeus commented on the progress of peace talks to date, stating, "The prospect for reconciliation with senior Taliban leaders certainly looms out there...and there have been approaches at (a) very senior level that hold some promise."[223]