Aguazuque

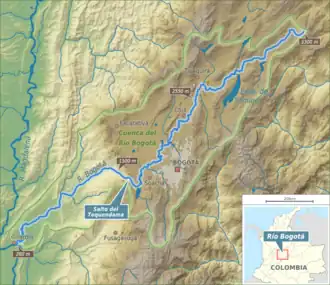

Aguazuque is a pre-Columbian archaeological site located in the western part of the municipality Soacha, close to the municipalities Mosquera and San Antonio del Tequendama in Cundinamarca, Colombia. It exists of evidences of human settlement of hunter-gatherers and in the ultimate phase primitive farmers. The site is situated on the Bogotá savanna, the relatively flat highland of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense close to the present-day course of the Bogotá River at an altitude of 2,600 metres (8,500 ft) above sea level. Aguazuque is just north of another Andean preceramic archaeological site; the rock shelter Tequendama and a few kilometres south of Lake Herrera. The artefacts found mostly belong to the preceramic period, and have been dated to 5025 to 2725 BP (3000 to 700 BCE). Thus, the younger finds also pertain to the later ceramic Herrera Period. There were some difficulties in dating of the uppermost layer due to modern agricultural activity in the area; the sediments of the shallower parts were disturbed.

Location within Colombia | |

| Location | Soacha, Cundinamarca |

|---|---|

| Region | Bogotá savanna, Altiplano Cundiboyacense, |

| Coordinates | 4°36′08″N 74°16′35″W |

| Altitude | 2,601 m (8,533 ft) |

| Type | Open area settlement |

| Part of | Pre-Muisca sites |

| Area | 76 m2 (820 sq ft) |

| History | |

| Periods | Andean preceramic-Herrera |

| Cultures | Herrera |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Correal |

| Public access | Yes |

At Aguazuque multiple palaeoanthropological finds have been made; stone and bone tools, remains of fireplaces and a multitude of pre-Columbian foods, primitive circular housing, various burial sites of individual and group interments and in the youngest dated layers, evidences of ceramics.

The site represents a transition from a hunter-gatherer culture towards the earliest evidence of agriculture. A phase of settlement is attested where the people moved away from the caves and rock shelters and started inhabiting open area grounds.

Investigation of Aguazuque has been conducted since 1986, mainly by archaeologist Gonzalo Correal Urrego who published the results of his studies in the book Aguazuque - evidencias de cazadores, recolectores y plantadores en la altiplanicie de la Cordillera Oriental in 1990.[1][2]

Etymology

The site Aguazuque is named after the Hacienda Aguazuque that was built west of the capital Bogotá in the early 17th century.[3]

Background

The history of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense goes back to the prehistorical era. The oldest dated evidence of human settlement on the high plateau in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes has been found in El Abra, within the municipality of Zipaquirá, Cundinamarca. At this rock shelter on the northern edge of the Bogotá savanna, stone tools and chopper cores have been carbon dated at 12,500 years BP. Other early sites of inhabitation of the area have been discovered at Tibitó (11,400 BP), Tequendama (11,000 BP) and Checua (8500 BP), with later settlements in Mosquera (3135 BP), Chía (3120 BP), Junín, Zipacón and Tausa.[4][5] Younger ceramic artefacts were found around Lake Herrera, the namesake of the Herrera Period that is defined as from 800 BC to 800 AD.[6] The period from 800 to 1537 AD, when the Spanish conquered this area, is characterised by one of the four grand civilisations of the Americas; the Muisca period.

Soacha, today the most populated satellite city of the Colombian capital, was an important location for pre-Columbian settlement. Apart from Aguazuque, various other sites have been discovered in the vicinity of Soacha. For example, in 2014, the largest pre-Columbian town has been discovered in Soacha, with the remains of 2200 people, more than 600 ceramic pots and various spindles and tunjos.[7][8][9][10]

The name Soacha is derived from the Muysccubun words for Sun; Súa (with the Sun god Sué) and man; chá.[11]

Aguazuque

The archaeological remains of Aguazuque were found in an oval elevated area west of the Bogotá River, that forms a bend around this higher ground. Aguazuque is located on the southwestern part of the Bogotá savanna and is surrounded by higher hills reaching altitudes of up to 2,850 metres (9,350 ft). The climate is cool, with an average temperature of 13 °C (55 °F).[12] Compared to other parts of the Bogotá savanna, the area of Aguazuque has relatively little rainfall.[13] Geologically, Aguazuque is located on an anticlinal part of the Eastern Ranges with sandstones of the Late Cretaceous Guadalupe Group outcropping nearby. The top sediments are of Late Pleistocene and early Holocene age and contain sandstones and claystones of the former Lake Humboldt and various beds of volcanic ash. Fossil remains of Pleistocene megafauna have been found in Mosquera and were dated to 20,000 years BP.[14] The area of the site is 76 square metres (820 sq ft) and remains have been analysed to a depth of 2 metres (6.6 ft).[15]

Artefacts

The stone artefacts uncovered are very similar in character to those found at El Abra and Tequendama and consist of tools mainly made of chert from the Guadalupe Group. The tools comprise various kinds of scrapers, knives, perforating tools, burins, spokeshaves, maceheads and round mortars and flat milling stones. Most of the artefacts originate from the nearby chert, with some tools made from shales of the Villeta Group and more allochthonous basalt tools, coming from farther west, around the Magdalena River, provenance of the Central Ranges of the Colombian Andes.[16] Apart from tools, Aguazuque is characterised by a large percentage of flakes resulting from the lithic reduction; the process of elaboration of the tools; in total 3868 samples, between 60 and 70% of the lithic fragments found were of this type.[17]

Other artefacts found were made of bones and shells, such as beads, spear points, perforating tools, knives and scrapers. The latter formed the majority of bone tools found, accounting for 55 to 75% of the bone artefacts found.[18]

Flora, fauna and diet

_(15498893548).jpg.webp)

In all of the layers of the Aguazuque site, remains of fauna have been uncovered. The fauna, part of the cuisine of the inhabitants of Aguazuque, consisted of mammals, reptiles, birds, fish and invertebrates such as gastropods, fresh water oysters and crustaceans.

As at the other sites on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the main part of the diet of the people was formed by white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Other mammals included little red brocket (Mazama rufina), guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus), nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), crab-eating fox (Dusicyon thous), spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus), ocelot (Felis pardalis), puma (Felis concolor), lowland paca (Agouti paca), Agouti taczamawskii, Dasyprocta, ring-tailed coati (Nasua nasua), western mountain coati (Nasuella olivacea), common opossum (Didelphis marsupialis) and collared anteater (Tamandua tetradactyla).[19] Reptiles consisted of the turtle Kinosternon postinginale and remains of caimans, indicating hunting in terrains much farther to the west; the Magdalena River.[20][21]

Fish was coming from the various lakes, rivers and wetlands dotting the Bogotá savanna, that originally were part of Lake Humboldt. Fish remains consisted of Eremophilus mutisii, Pygidium bogotense and Grundulus bogotensis.[20] Bird remains included the Andean guan (Penelope montagnii), Anatidae, Ralidae and the scaly-naped parrot (Amazona mercenaria).[20] The invertebrates comprised Drymaeus gratus, Plekocheilus coloratus, Plekocheilus succionoides, fresh water oysters and fresh water crabs of the family Pseudothelfhusidae, possibly Neostrengeria magropa.[22]

In terms of species of flora, Aguazuque has provided evidence of early agriculture, based on seeds of Cucurbita pepo.[23] Other plant remains were analysed as Hieronyma macrocarpa, Oxalis tuberosa, Dioscorea trífida and various remains of Bromeliaceae, Rubiaceae and Gramineae. Species of mushrooms suggest their addition to the diet of the hunter-gatherers of Aguazuque.[24]

Burial sites

Within the area of Aguazuque, fifty-nine burial sites have been discovered, consisting of single, double and mass graves. The bodies were buried on either the right or the left side, or lying on their backs. As was common in the later Muisca mummification culture, the bodies were interred with their arms crossed over the thorax and the legs folded onto the abdomen.

One of the collective sites contained the remains of 23 adults (men and women) and children.[25] It has been theorised that these people fell victim to epidemics, of which in the remains no traces were found.[26] The burial sites showed evidence of ritual and beliefs in afterlife; the bodies were surrounded by stone tools, such as scrapers and mortars, and some pieces were decorated with red or black colours. Food offerings, such as the meat of the white-tailed deer, guinea pigs and Tayassu pecari accompanied the buried.[27] An isolated body was adorned with colourful painted pieces of rock.[28] Similar to what has been found in Tequendama, some of the buried people may have been characterised by rituals of cannibalism.[29] This is evidenced further by the discovery of mutilated and coloured skeletal remains in Aguazuque.[30]

Paleopathological analysis has provided information on the people; the average brain volume was around 1,400 cubic centimetres (85 cu in), spread from 1,240 cubic centimetres (76 cu in) to 1,480 cubic centimetres (90 cu in) and the body length around 160 centimetres (63 in).[31] Osteoarthritis has been found in 73% of the individuals and other diseases such as syphilis, treponematosis, osteoperiostitis and osteoperosis were common.[32] Different from remains of similar age found on the Altiplano, such as Gachalá, Nemocón and Tequendama, where no evidence of caries was discovered, in Aguazuque the human dental remains showed ample evidence of caries.[33] Electron paramagnetic resonance of tooth enamel has provided an age of 3256 ± 196 years BP.[34]

Burial sites of animals have also been found, where turtles, parrots and foxes were located in isolated small graves.[35]

History of settlement

The evidence for human settlements at Aguazuque consists of circular slightly excavated structures, surrounded by vertically inward inclined bones of deer, or poles of wood. The round areas had a diameter of between 2 metres (6.6 ft) and 4 metres (13 ft) and contained ash and carbon remains on the floor. Using animal and shell pigments, the floors were painted red or covered with sandstone fragments and volcanic ash. The remains of the houses were mostly circular, and near them were many fireplaces.[36]

The oldest evidence for settlement has been dated to 5025 ± 40 years Before Present (around 3000 BCE). This layer is followed by younger occupation dated at 3850 ± 35 years, 3400 to 2800 BP and the second-youngest zone at 2725 ± 35 years BP. The uppermost layer has been disturbed by modern agricultural activity and provided no dates. The different layers of Aguazuque were similar in character in terms of the tools found, and in the abundance of deer, the main meat for the inhabitants of the Bogotá savanna. The sequence of the layers from bottom to top based on the abundance of guinea pig remains, showed that their presence as domesticated animals varied through time. The domestication of guinea pigs is also evidenced in nearby Tequendama.

The percentage of hunted deer was highest in the uppermost layer where the caiman bones have also been found, suggesting a time of greater interaction with the lower altitude tropical zones of the Andes. The early evidence for agriculture has been found in the middle section of the sequence, as has been discovered in Zipacón where the agricultural activity has been dated at 3270 years BP.[37] Only in the uppermost beds, the evidence of ceramics has been found, that could be dated to Early Herrera; around 2800 years BP.[38]

Named after Aguazuque

Aguazuque is featured as one of the names appearing in the grand-strategy video game Europa Universalis IV in the playable nation of the Muisca.[39]

See also

References

- (in Spanish) La colonia vive en Canoas - El Tiempo

- (in Spanish) Curriculum Vitae Gonzalo Correal Urrego Archived 2016-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 21

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 9

- Groot de Mahecha, 1992

- (in Spanish) Chronology of pre-Columbian periods: Herrera and Muisca

- (in Spanish) Herrera Period evidence in Soacha - El Espectador

- (in Spanish) Largest Herrera Period village in Soacha Archived 2016-06-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Archaeologists uncover remains of pre-Columbian village in central Colombia

- (in Spanish) Dating of the Soacha Herrera Period site Archived 2016-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Official website Soacha Archived 2016-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 13

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 14

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 16

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 23

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 30

- Correal Urrego, 1990, pp. 35–53

- Correal Urrego, 1990, pp. 54–78

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 79

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 80

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 263

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 113

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p.248

- Correal Urrego, 1990, pp. 249–250

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 139

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 259

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 141

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 142

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 152

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p.153

- Correal Urrego, 1990, pp.165–194

- Correal Urrego, 1990, pp. 198–222

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 231

- Datación de restos fósiles humanos provenientes de Aguazuque y Checua (Cundinamarca) usando resonancia paramagnética electrónica (epr) - abstract - Universidad Nacional

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 237

- Correal Urrego, 1990, pp. 237–244

- Correal Urrego, 1990, pp. 256–264

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 264

- Muisca names Europa Universalis IV - GitHub

Bibliography

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Aguazuque - evidencias de cazadores, recolectores y plantadores en la altiplanicie de la Cordillera Oriental - Aguazuque: Evidence of hunter-gatherers and growers on the high plains of the Eastern Ranges, 1-316. Banco de la República: Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 1992. Checua: Una secuencia cultural entre 8500 y 3000 años antes del presente - Checua: a cultural sequence between 8500 and 3000 years before present, 1-95. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.