al-Ma'mun

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid (Arabic: أبو العباس عبد الله بن هارون الرشيد, romanized: Abū al-ʿAbbās ʿAbd Allāh ibn Hārūn ar-Rashīd; 14 September 786 – 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name al-Ma'mun (Arabic: المأمون, romanized: al-Maʾmūn), was the seventh Abbasid caliph, who reigned from 813 until his death in 833. He succeeded his half-brother al-Amin after a civil war, during which the cohesion of the Abbasid Caliphate was weakened by rebellions and the rise of local strongmen; much of his domestic reign was consumed in pacification campaigns. Well educated and with a considerable interest in scholarship, al-Ma'mun promoted the Translation Movement, the flowering of learning and the sciences in Baghdad, and the publishing of al-Khwarizmi's book now known as "Algebra". He is also known for supporting the doctrine of Mu'tazilism and for imprisoning Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, the rise of religious persecution (mihna), and for the resumption of large-scale warfare with the Byzantine Empire.

| al-Ma'mun المأمون | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gold dinar of al-Ma'mun, minted in Egypt in 830/1 | |||||

| 7th Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 27 September 813 – 7 August 833 | ||||

| Predecessor | al-Amin | ||||

| Successor | al-Mu'tasim | ||||

| Born | 14 September 786 Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Died | 7 August 833 (aged 46) Tarsus, Abbasid Caliphate, now Mersin Province, Turkey | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Consort | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | ||||

| Father | Harun al-Rashid | ||||

| Mother | Umm Abdallah Marajil | ||||

| Religion | Islam[note 1] | ||||

Birth and education

Abdallah, the future al-Ma'mun, was born in Baghdad on the night of the 13 to 14 September 786 CE to Harun al-Rashid and his concubine Marajil, from Badghis. On the same night, which later became known as the "night of the three caliphs", his uncle al-Hadi died and was succeeded by Ma'mun's father, Harun al-Rashid, as ruler of the Abbasid Caliphate.[1] Marajil died soon after his birth, and Abdallah was raised by Harun al-Rashid's wife, Zubayda, herself of high Abbasid lineage as the granddaughter of Caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775).[2] As a young prince, Abdallah received a thorough education: al-Kisa'i tutored him in classical Arabic, Abu Muhammad al-Yazidi in adab, and he received instruction in music and poetry. He was trained in fiqh by al-Hasan al-Lu'lu'i, showing particular excellence in the Hanafi school, and in the hadith, becoming himself active as a transmitter.[2] According to M. Rekaya, "he was distinguished by his love of knowledge, making him the most intellectual caliph of the Abbasid family, which accounts for the way in which his caliphate developed".[2]

Appointment as successor and Governor of Khurasan

Although Abdallah was the oldest of his sons, in 794 Harun named the second-born Muhammad, born in April 787 to Zubayda, as the first in line of succession. This was the result of family pressure on the Caliph, reflecting Muhammad's higher birth, as both parents descended from the Abbasid dynasty; indeed, he remained the only Abbasid caliph to claim such descent. Muhammad received the oath of allegiance (bay'ah) with the name of al-Amin ("The Trustworthy"), first in Khurasan by his guardian, the Barmakid al-Fadl ibn Yahya, and then in Baghdad.[2] Abdallah was recognized as second heir only after entering puberty, in 799, under the name al-Ma'mun ("The Trusted One"), with another Barmakid, Ja'far ibn Yahya, as his guardian. At the same time, a third heir, al-Qasim, named al-Mu'tamin, was appointed, under the guardianship of Abd al-Malik ibn Salih.[2]

These arrangements were confirmed and publicly proclaimed in 802, when Harun and the most powerful officials of the Abbasid government made the pilgrimage to Mecca. Al-Amin would succeed Harun in Baghdad, but al-Ma'mun would remain al-Amin's heir and would additionally rule over an enlarged Khurasan.[2] This was an appointment of particular significance, as Khurasan had been the starting point of the Abbasid Revolution which brought the Abbasids to power, and retained a privileged position among the Caliphate's provinces. Furthermore, the Abbasid dynasty relied heavily on Khurasanis as military leaders and administrators. Many of the original Khurasani Arab army (Khurasaniyya) that came west with the Abbasids were given estates in Iraq and the new Abbasid capital, Baghdad, and became an elite group known as the abnāʾ al-dawla ("sons of the state/dynasty").[3][4] This large-scale presence of an Iranian element in the highest circles of the Abbasid state, with the Barmakid family as its most notable representatives, was certainly a factor in the appointment of al-Ma'mun, linked through his mother with the eastern Iranian provinces, as heir and governor of Khurasan.[5] The stipulations of the agreement, which were recorded in detail by the historian al-Tabari, accorded al-Mamun's Khurasani viceroyalty extensive autonomy. However, modern historians consider that these accounts may have been distorted by later apologists of al-Ma'mun in the latter's favour.[6] Harun's third heir, al-Mu'tamin, received responsibility over the frontier areas with the Byzantine Empire in Upper Mesopotamia and Syria.[2][7]

Very quickly, the latent rivalry between the two brothers had important repercussions: almost immediately after the court returned to Baghdad in January 803, the Abbasid elites were shaken by the abrupt fall of the Barmakid family from power. On the one hand, this event may reflect the fact that the Barmakids had become indeed too powerful for the Caliph's liking, but its timing suggests that it was tied to the succession issue as well: with al-Amin siding with the abnāʾ and al-Ma'mun with the Barmakids, and the two camps becoming more estranged every day, if al-Amin was to have a chance to succeed, the power of the Barmakids had to be broken.[2][8][9]

Al-Fadl ibn Sahl, a Kufan of Iranian origin whose father had converted to Islam and entered Barmakid service, replaced Ja'far ibn Yahya as al-Ma'mun's tutor. In 806 he also became al-Ma'mun's secretary (katib), an appointment that marked him out as the chief candidate for the vizierate should al-Ma'mun succeed to the throne.[2] In 804, al-Ma'mun married his cousin, Umm Isa, a daughter of the Caliph al-Hadi (r. 785–786). The couple had two sons, Muhammad al-Asghar and Abdallah.[2]

The years after the fall of the Barmakids saw an increasing centralization of the administration and the concomitant rise of the influence of the abnāʾ, many of whom were now dispatched to take up positions as provincial governors and bring these provinces under closer control from Baghdad.[9] This led to unrest in the provinces, especially Khurasan, where local elites had a long-standing rivalry with the aabnāʾ and their tendency to control the province (and its revenues) from Iraq.[10] The harsh taxation imposed by a prominent member of the abnāʾ, Ali ibn Isa ibn Mahan, even led to a revolt under Rafi ibn al-Layth, which eventually forced Harun himself, accompanied by al-Ma'mun and the powerful chamberlain (hajib) and chief minister al-Fadl ibn al-Rabi, to travel to the province in 808. Al-Ma'mun was sent ahead with part of the army to Merv, while Harun stayed at Tus, where he died on 24 March 809.[2][9][11]

Abbasid civil war

In 802 Harun al-Rashid, father of al-Maʾmūn and al-Amin, ordered that al-Amin succeed him, and al-Ma'mun serve as governor of Khurasan and as caliph after the death of al-Amin. In the last days of Harun's life his health was declining and saw in a dream Musa ibn Jafar sitting in a chamber praying and crying, which made Harun remember how hard he had struggled to establish his own caliphate. He knew the personalities of both his sons and decided that for the good of the Abbasid dynasty, al-Maʾmūn should be caliph after his death, which he confided to a group of his courtiers. One of the courtiers, Fadl ibn Rabi', did not abide by Harun's last wishes and convinced many in the lands of Islam that Harun's wishes had not changed. Later the other three courtiers of Harun who had sworn loyalty to Harun by supporting al-Maʾmūn, namely, 'Isa Jarudi, Abu Yunus, and Ibn Abi 'Umran, found loopholes in Fadl's arguments, and Fazl admitted Harun had appointed al-Maʾmūn after him, but, he argued, since Harun was not in his right mind, his decision should not be acted upon. Al-Maʾmūn was reportedly the older of the two brothers, but his mother was a Persian woman while al-Amin's mother was a member of the reigning Abbasid family. After al-Rashid's death in 809, the relationship between the two brothers deteriorated. In response to al-Ma'mun's moves toward independence, al-Amin declared his own son Musa to be his heir. This violation of al-Rashid's testament led to a succession struggle. Al-Amin assembled a massive army at Baghdad with 'Isa ibn Mahan at its head in 811 and invaded Khorasan, but al-Maʾmūn's general Tahir ibn al-Husayn (d. 822) destroyed the army and invaded Iraq, laying siege to Baghdad in 812. In 813 Baghdad fell, al-Amin was beheaded, and al-Maʾmūn became the undisputed Caliph.[12]

Internal strife

Sahl ibn Salama al-Ansari

There were disturbances in Iraq during the first several years of al-Maʾmūn's reign, while the caliph was in Merv (near present-day Mary, Turkmenistan). On 13 November 815, Muhammad ibn Ja'far al-Sadiq (al-Dibaj) claimed the Caliphate for himself in Mecca. He was defeated and he quickly abdicated asserting that he had only become caliph on news that al-Ma'mun had died. Lawlessness in Baghdad led to the formation of neighborhood watches with religious inspiration, with two notable leaders being Khalid al-Daryush and Sahl ibn Salama al-Ansari. Sahl adopted the slogan, la ta'a lil- makhluq fi ma'siyat al-khaliq, or 'no obedience to the creature in disobedience of the Creator'[13] (originally a Kharijite slogan),[14] alluding to what he saw as "the conflict ... between God's will and Caliphal authority". "Most" of the leadership of this vigilante movement came from the sulaahd ("men of good will of the neighborhoods and blocks") and from "popular preachers" (as both Khalid al-Daryush and Sahl ibn Salama al-Ansari were); its followers were called the 'amma, (the common people).[13] The volunteers of the movement were known as mutawwi'a, which was the same name given to "volunteers for frontier duty and for the holy war against Byzantium".[14] Sahl's and movement influence was such that military chiefs first "delayed capitulation to al-Ma'mun" and adopted Sahl's religious "formula" until they became alarmed at his power and combined to crush him in 817–18 CE.[15]

Imam al-Rida

In A.H. 201 (817 AD) al-Ma'mun named Ali ar-Rida (the sixth-generation descendant of Ali and the eighth Shia Imam) as his heir as caliph. This move may have been made to appease Shi'ite opinion in Iraq and "reconcile the 'Alid and 'Abbasid branches of the Hashimite family", but in Baghdad it caused the Hashimites—supported by "military chiefs of al-Harbiyya, including Muttalib and 'Isa ibn Muhammad"—to depose al-Ma'mun and elect Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi Caliph.[15]

According to Shia sources, the deposing of al-Ma'um in Baghdad was not out of opposition to the wise and pious Imam Reza, but because of rumors spread by Fazl ibn Sahl. Al-Ma'mun moved Imam Reza to Merv in hopes of keeping watch over him, but was foiled by the Imam's growing popularity there. People from all over the Muslim world traveled to meet the prophet's grandson and listen to his teachings and guidance (according to these sources). In an attempt to humiliate the Imam, al-Ma'mun set him up with the greatest scholars of the world's religions, but the Imam prevailed and then informed al-Ma'mun that his grand vizier, Fazl ibn Sahl, had withheld important information from him.[16]

In Baghdad, al-Maʾmūn was unseated and replaced by Ibrahim ibn Mehdi not because al-Maʾmūn's naming Imam Reza as his heir was unpopular, but because of "rumors" spread by Fazl ibn Sahl.

Seeking to put down the rebellion in Baghdad, al-Ma'mun set out for the city on 12 April 818. At Tus, he stopped to visit his father's grave. However, when they reached the town of Sarakhs, his vizier, Fazl ibn Sahl, was assassinated, and when they reached Tus, the Imam was poisoned. Al-Ma'mūn ordered that the Imam be buried next to the tomb of his own father, Harun al-Rashid, and showed extreme sorrow in the funeral ritual and stayed for three days at the place. Nonetheless, Shia tradition states he was killed on orders of al-Ma'mun, and according to Wilferd Madelung the unexpected death of both the vizier and the successor, "whose presence would have made any reconciliation with the powerful ʿAbbasid opposition in Baghdad virtually impossible, must indeed arouse strong suspicion that Ma'mun had had a hand in the deaths."[17][18]

Following the death of Imam Reza, a revolt took place in Khurasan. Al-Ma’mun tried unsuccessfully to absolve himself of the crime.[19]

After arrival in Baghdad

The rebel forces in Baghdad splintered and wavered in opposition to al-Ma'mun. According to scholar and historian al-Tabari (839–923 CE), al-Ma'mun entered Baghdad on 11 August 819.[20] He wore green and had others do so. Informed that compliance with this command might arouse popular opposition to the colour, on 18 August he reverted to traditional Abbasid black. While Baghdad became peaceful, there were disturbances elsewhere. In AH 210 (825–826 CE) Abdullah ibn Tahir al-Khurasani secured Egypt for al-Ma'mun, freeing Alexandria from Andalusians and quelling unrest. The Andalusians moved to Crete, where al-Tabari records their descendants were still living in his day (see Emirate of Crete). Abdallah returned to Baghdad in 211 Hijri (826–827 CE) bringing the defeated rebels with him.

Also, in 210 Hijri (825–826 CE), there was an uprising in Qum sparked by complaints about taxes. After it was quashed, the tax assessment was set significantly higher. In 212 Hijri (827–828 CE), there was an uprising in Yemen. In 214 (829–30 CE), Abu al-Razi, who had captured one Yemeni rebel, was killed by another. Egypt continued to be unquiet. Sindh was rebellious. In 216 (831–832 CE), Ghassan ibn 'Abbad subdued it. An ongoing problem for al-Ma'mun was the uprising headed by Babak Khorramdin. In 214 Babak routed a Caliphate army killing its commander Muhammad ibn Humayd.

Wars with Byzantium

By the time al-Ma'mun became Caliph, the Arabs and the Byzantine Empire had settled down into border skirmishing, with Arab raids deep into Anatolia to capture booty and Christians to be enslaved. The situation changed however with the rise to power of Michael II in 820 AD. Forced to deal with the rebel Thomas the Slav, Michael had few troops to spare against a small Andalusian invasion of 40 ships and 10,000 men against Crete, which fell in 824 AD. A Byzantine counter offensive in 826 AD failed miserably. Worse still was the invasion of Sicily in 827 by Arabs of Tunis. Even so, Byzantine resistance in Sicily was fierce and not without success whilst the Arabs became quickly plagued by internal squabbles. That year, the Arabs were expelled from Sicily but they were to return.

In 829, Michael II died and was succeeded by his son Theophilos. Theophilos experienced mixed success against his Arab opponents. In 830 AD the Arabs returned to Sicily and, after a year-long siege, took Palermo. For the next 200 years they were to remain there to complete their conquest, which was never short of Christian counters. Al-Ma'mun meanwhile launched an invasion of Anatolia in 830 AD, taking a number of Byzantine forts; he spared the surrendering Byzantines. Theophilos, for his part, captured Tarsus in 831. The next year, learning the Byzantines had killed some sixteen hundred people, al-Ma'mun returned. This time some thirty forts fell to the Caliphate's forces, with two Byzantine defeats in Cappadocia.

Theophilos wrote to al-Ma'mun. The Caliph replied that he carefully considered the Byzantine ruler's letter, noticed it blended suggestions of peace and trade with threats of war and offered Theophilos the options of accepting the shahada, paying tax or fighting. Al-Ma'mun made preparations for a major campaign, but died on the way while leading an expedition in Tyana.

Al-Ma'mun's relations with the Byzantines are marked by his efforts in the translation of Greek philosophy and science. Al-Ma'mun gathered scholars of many religions at Baghdad, whom he treated magnificently. He sent an emissary to the Byzantine Empire to collect the most famous manuscripts there, and had them translated into Arabic.[21] As part of his peace treaty with the Byzantine Emperor, al-Ma'mun was to receive a number of Greek manuscripts annually, one of these being Ptolemy's astronomical work, the Almagest.[22]

al-Ma'mun's reign

.jpg.webp)

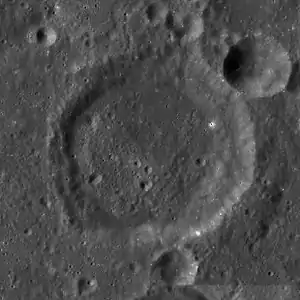

Al-Ma'mun conducted, in the plains of Mesopotamia, two astronomical operations intended to achieve a degree measurement (al-Ma'mun's arc measurement). The crater Almanon on the moon is named in recognition of his contributions to astronomy.

Al-Ma'mun's record as an administrator is also marked by his efforts toward the centralization of power and the certainty of succession. The Bayt al-Hikma, or House of Wisdom, was established during his reign.[23] The ulama emerged as a real force in Islamic politics during al-Ma'mun's reign for opposing the mihna, which was initiated in 833, four months before he died.

Michael Hamilton Morgan in his book "Lost History" describes al-Ma'mun as a man who 'Loves Learning.' al-Ma'mun once defeated a Byzantine Emperor in a battle and as a tribute, he asked for a copy of Almagest, Ptolemy's Hellenistic compendium of thoughts on astronomy written around AD 150[24]

The 'mihna', is comparable to Medieval European inquisitions in the sense that it involved imprisonment, a religious test, and a loyalty oath. The people subject to the mihna were traditionalist scholars whose social influence was uncommonly high. Al-Ma'mun introduced the mihna with the intention of centralizing religious power in the caliphal institution and testing the loyalty of his subjects. The mihna had to be undergone by elites, scholars, judges and other government officials, and consisted of a series of questions relating to theology and faith. The central question was about the createdness of the Qur'an, if the interrogatee stated he believed the Qur'an to be created, rather than coeternal with God, he was free to leave and continue his profession.

The controversy over the mihna was exacerbated by al-Ma'mun's sympathy for Mu'tazili theology and other controversial views. Mu'tazili theology was deeply influenced by Aristotelian thought and Greek rationalism, and stated that matters of belief and practice should be decided by reasoning. This opposed the traditionalist and literalist position of Ahmad ibn Hanbal and others, according to which everything a believer needed to know about faith and practice was spelled out literally in the Qur'an and the Hadith. Moreover, the Mu'tazilis stated that the Qur'an was created rather than coeternal with God, a belief that was shared by the Jahmites and parts of Shi'a, among others, but contradicted the traditionalist-Sunni opinion that the Qur'an and the Divine were coeternal.

During his reign, alchemy greatly developed. Pioneers of the science were Jabir Ibn Hayyan and his student Yusuf Lukwa, who was patronized by al-Ma'mun. Although he was unsuccessful in transmuting gold, his methods greatly led to the patronization of pharmaceutical compounds.[25]

Al-Ma'mun was a pioneer of cartography having commissioned a world map from a large group of astronomers and geographers. The map is presently in an encyclopedia in Topkapi Sarai, a Museum in Istanbul. The map shows large parts of the Eurasian and African continents with recognizable coastlines and major seas. It depicts the world as it was known to the captains of the Arab sailing dhows which used the monsoon wind cycles to trade over vast distances (by the 9th century, Arab sea traders had reached Guangzhou, in China). The maps of the Greeks and Romans reveal a good knowledge of closed seas like the Mediterranean but little knowledge of the vast ocean expanses beyond.[26]

Although al-Mahdi had proclaimed that the caliph was the protector of Islam against heresy, and had also claimed the ability to declare orthodoxy, religious scholars in the Islamic world believed that al-Ma'mun was overstepping his bounds in the mihna. The penalties of the mihna became increasingly difficult to enforce as the ulema became firmer and more united in their opposition. Although the mihna persisted through the reigns of two more caliphs, al-Mutawakkil abandoned it in 851.

The ulema and the major Islamic law schools became truly defined in the period of al-Ma'mun, and Sunnism—as a religion of legalism—became defined in parallel. Doctrinal differences between Sunni and Shi'a Islam began to become more pronounced. Ibn Hanbal, the founder of the Hanbali legal school, became famous for his opposition to the mihna. Al-Ma'mun's simultaneous opposition and patronage of intellectuals led to the emergence of important dialogues on both secular and religious affairs, and the Bayt al-Hikma became an important center of translation for Greek and other ancient texts into Arabic. This Islamic renaissance spurred the rediscovery of Hellenism and ensured the survival of these texts into the European Renaissance.

Al-Ma'mun had been named governor of Khurasan by Harun, and after his ascension to power, the caliph named Tahir as governor for his military services in order to assure his loyalty. It was a move that al-Ma'mun soon regretted, as Tahir and his family became entrenched in Iranian politics and became increasingly powerful in the state, contrary to al-Ma'mun's desire to centralize and strengthen Caliphal power. The rising power of the Tahirid family became a threat as al-Ma'mun's own policies alienated them and his other opponents.

Al-Ma'mun also attempted to divorce his wife during his reign, who had not borne him any children. His wife hired a Syrian judge of her own before al-Ma'mun was able to select one himself; the judge, who sympathized with the caliph's wife, refused the divorce. Following al-Ma'mun's experience, no further Abbasid caliphs were to marry, preferring to find their heirs in the harem.

Al-Ma'mun, in an attempt to win over the Shi'a Muslims to his camp, named the eighth Imam, Ali ar-Rida, his successor, if he should outlive al-Ma'mun. Most Shi'ites realized, however, that ar-Rida was too old to survive him and saw al-Ma'mun's gesture as empty; indeed, al-Ma'mun poisoned Ali ar-Rida who then died in 818. The incident served to further alienate the Shi'ites from the Abbasids, who had already been promised and denied the Caliphate by Abu al-'Abbas.

The Abbasid empire grew somewhat during the reign of al-Ma'mun. Hindu rebellions in Sindh were put down, and most of Afghanistan was absorbed with the surrender of the leader of Kabul. Mountainous regions of Iran were brought under a tighter grip of the central Abbasid government, as were areas of Turkestan.

In 832, al-Ma'mun led a large army into Egypt to put down the last great Bashmurite revolt.[27]

Personal characteristics

Al-Tabari (v. 32, p. 231) describes al-Ma'mun as of average height, light complexion, handsome and having a long beard that lost its dark colour as he aged. He relates anecdotes concerning the caliph's ability to speak concisely and eloquently without preparation, his generosity, his respect for Muhammad and religion, his sense of moderation, justice, his love of poetry and his insatiable passion for physical intimacy.

Ibn Abd Rabbih in his Unique Necklace (al-'iqd al-Farid), probably drawing on earlier sources, makes a similar description of al-Ma'mun, whom he described as of light complexion and having slightly blond hair, a long thin beard, and a narrow forehead.

Family

Al-Ma'mun's first wife was Umm Isa, a daughter of his uncle al-Hadi (r. 785–786), whom he married when he was eighteen years old. They had two sons, Muhammad al-Asghar, and Abdallah.[2] Another wife was Buran, the daughter of al-Ma'mun's vizier, al-Hasan ibn Sahl.[28] She was born as Khadija[28] on 6 December 807.[29] Al-Ma'mun married her in 817, and consummated the marriage with her in December 825–January 826 in the town of Fam al-Silh.[28] She died on 21 September 884.[29]

Al-Ma'mun had also numerous concubines.[2] One of them, Sundus, bore him five sons, among whom was al-Abbas, who rose to become a senior military commander at the end of al-Ma'mun's reign and a contender for the throne.[30] Another wife or concubine was Arib.[31] Born in 797,[32] she claimed to be the daughter of Ja'far ibn Yahya, the Barmakid, stolen and sold as a child when the Barmakids fell from power. She was brought by al-Amin, who then sold her to his brother.[31] She was a noted poet, singer, and musician.[31] She died at Samarra in July–August 890, aged ninety-six.[32] Another concubine was Bi'dah al-Kabirah. She was also a singer, and had been a slave of Arib.[33] She died on 10 July 915. Abu Bakr, the son of Caliph al-Muhtadi, led the funeral prayers.[34] Another concubine was Mu'nisah, a Greek.[35]

Al-Ma'mun had two daughters. One was Umm Habib, who married Ali ibn Musa al-Rida, and the other was Umm al-Fadl, who married Muhammad ibn Ali bin Musa.[36]

Death and legacy

Al-Tabari recounts how al-Ma'mun was sitting on the river bank telling those with him how splendid the water was. He asked what would go best with this water and was told a specific kind of fresh dates. Noticing supplies arriving, he asked someone to check whether such dates were included. As they were, he invited those with him to enjoy the water with these dates. All who did this fell ill. Others recovered, but al-Ma'mun died. He encouraged his successor to continue his policies and not burden the people with more than they could bear. This was on 9 August 833.[37]

Al-Ma'mun died near Tarsus. The city's major mosque (Tarsus Grand Mosque), contains a tomb reported to be his. Al-Ma'mun had made no official provisions for his succession. His son, al-Abbas, was old enough to rule and had acquired experience of command in the border wars with the Byzantines, but had not been named heir.[38] According to the account of al-Tabari, on his deathbed al-Ma'mun dictated a letter nominating his brother, rather than al-Abbas, as his successor,[39] and Abu Ishaq was acclaimed as caliph on 9 August, with the Laqab of al-Mu'tasim (in full al-Muʿtaṣim bi’llāh, "he who seeks refuge in God").[40] It is impossible to know whether this reflects actual events, or whether the letter was an invention and Abu Ishaq merely took advantage of his proximity to his dying brother, and al-Abbas's absence, to propel himself to the throne. As Abu Ishaq was the forefather of all subsequent Abbasid caliphs, later historians had little desire to question the legitimacy of his accession, but it is clear that his position was far from secure: a large part of the army favoured al-Abbas, and a delegation of soldiers even went to him and tried to proclaim him as the new Caliph. Only when al-Abbas refused them, whether out of weakness or out of a desire to avoid a civil war, and himself took the oath of allegiance to his uncle, did the soldiers acquiesce in al-Mu'tasim's succession.[41][42]

Almanon, a lunar impact crater that lies in the rugged highlands in the south-central region of the Moon, was named after al-Ma'mun.[43]

Al-Ma'mun was the last Abbasid caliph who had a one-word Laqab, his successors had laqab with suffixes like Billah or alā Allāh.

His nephew, Harun (future al-Wathiq) learned calligraphy, recitation and literature from his uncle, Caliph al-Ma'mun.[44] Later sources nickname him the "Little Ma'mun" on account of his erudition and moral character.[44]

Religious beliefs

Al-Maʾmūn's religious beliefs are a subject of controversy, to the point where other Abbasids,[45] as well as later Islamic scholars, called him a Shia Muslim. For instance, Sunni scholars al-Dhahabi, Ibn Kathir, Ibn Khaldun and al-Suyuti explicitly held the belief that al-Ma'mun was a Shi'a.[46] The arguments for his alleged Shi’ism include that, in 816/817, when Ali al-Ridha, the Prophet's descendant, refused designation as sole Caliph, al-Ma'mun officially designated him as his appointed successor. The official Abbasid coins were minted showing al-Ma'mun as a Caliph and al-Ridha as his successor.[47] Other arguments were that: the Caliphate's official black colour was changed to the Prophetic green; in 210 AH/825 CE, he wrote to Qutham b. Ja'far, the ruler of Medina, to return Fadak to the descendants of Muhammad through his daughter, Fatima; he restored nikah mut'ah, previously banned by Umar ibn al-Khattab, but practiced under Muhammad and Abu Bakr; in 211 AH/826 CE, al-Ma'mun reportedly expressed his antipathy to those who praised Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, and reportedly punished such people;[48] this later view of al-Suyuti however is questionable since it contradicts the fact that al-Ma’mun promoted scholars who openly defended Muawiyah, such as the Mu’tazilite scholar Hisham bin Amr al-Fuwati, who was a well-respected judge in the court of al-Ma’mun in Baghdad;[49] in 212 AH/827 CE, al-Ma'mun announced the superiority of Ali ibn Abu Talib over Abu Bakr and 'Umar b. al-Khattab;[48] in 833 CE, under the influence of Muʿtazila rationalist thought, he initiated the mihna ordeal, where he accepted the argument that the Quran was created at some point over the orthodox Sunni belief that the Book is the uncreated word of God.

However, Shi’ites condemn al-Ma'mun as well due to the belief that he was responsible for Ali al-Ridha's poisoning and eventual death in 818 CE. In the ensuing power struggle, other Abbasids sought to depose Ma'mun in favor of Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi, Ma'mun's uncle;[50] therefore, getting rid of al-Ridha was the only realistic way of retaining united, absolute, unopposed rule.[51] Al-Ma'mūn ordered that al-Ridha be buried next to the tomb of his own father, Harun al-Rashid, and showed extreme sorrow in the funeral ritual and stayed for three days at the place. Muhammad al-Jawad, Ali al-Ridha's son and successor, lived unopposed and free during the rest of al-Ma'mūn’s reign (till 833 CE). The Caliph summoned al-Jawad to Baghdad in order to marry his daughter, Ummul Fadhl. This apparently provoked strenuous objections by the Abbasids. According to Ya'qubi, al-Ma'mun gave al-Jawad one hundred thousand dirham and said, "Surely I would like to be a grandfather in the line of the Apostle of God and of Ali ibn Abu Talib."[52]

References

Citations

- Rekaya, M. (24 April 2012). "al-Maʾmūn". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Rekaya 1991, p. 331.

- El-Hibri 2010, p. 274.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 133–135.

- El-Hibri 2010, p. 282.

- El-Hibri 2010, pp. 282–283.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 142.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 142–143.

- El-Hibri 2010, p. 283.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 144.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 144–145.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1986). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates (2nd ed.). London and New York: Pearson Longman. pp. 148–150. ISBN 0-582-49312-9.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (1975). "Separation of state and religion in early Islamic society". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 6: 375. doi:10.1017/S0020743800025344. JSTOR 162750. S2CID 162409061. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (1975). "Separation of state and religion in early Islamic society". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 6: 376. doi:10.1017/S0020743800025344. JSTOR 162750. S2CID 162409061. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (1975). "Separation of state and religion in early Islamic society". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 6: 363–385. doi:10.1017/S0020743800025344. JSTOR 162750. S2CID 162409061. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- "Why was Imam al-Reza (A.S.) Invited to Khurasan?". Imam Reza Network. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- W. Madelung (1 August 2011). "Alī Al-Reżā, the eighth Imam of the Imāmī Shiʿites". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- al-Qarashi, Bāqir Sharif. The life of Imām 'Ali Bin Mūsā al-Ridā. Translated by Jāsim al-Rasheed. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Mavani, Hamid (2013). Religious Authority and Political Thought in Twelver Islam. New York: Routledge. pp. 276+. ISBN 978-1135044732. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- The History of al-Ṭabarī, v. 32, p. 95

- Tesdell, Lee S. (1999). "Greek Rhetoric and Philosophy in Medieval Arabic Culture: The State of the Research". In Poster, Carol; Utz, Richard (eds.). Discourses of Power: Grammar and Rhetoric in the Middle Ages. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. pp. 51–58. ISBN 0-8101-1812-2.

- Angelo, Joseph (2009). Encyclopedia of Space and Astronomy. p. 78. ISBN 978-1438110189.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (2002). A concise history of the Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8133-3885-9.

- Michael Hamilton Morgan "Lost History", p. 57

- E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam (1993), Vol. 4, p. 1011

- Rechnagel, Charles (15 October 2004). "World: Historian Reveals Incredible Contributions of Muslim Cartographers". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Gabra 2003, p. 112.

- Ibn al-Sāʿī 2017, p. 23.

- Ibn al-Sāʿī 2017, p. 26.

- Turner 2013.

- Ibn al-Sāʿī 2017, p. 15.

- Ibn al-Sāʿī 2017, p. 19.

- Ibn al-Sāʿī 2017, p. 20.

- Ibn al-Sāʿī 2017, p. 22.

- Ibn al-Sāʿī 2017, p. 32.

- Bosworth 1987, p. 82.

- Bosworth 1987, pp. 224–231.

- Kennedy 2006, p. 213.

- Bosworth 1987, pp. 222–223, 225.

- Bosworth 1991, p. 1.

- Kennedy 2006, pp. 213–215.

- Bosworth 1991, pp. 1–2 (esp. note 2).

- "Al-Ma'mun". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- Kan 2012, p. 548.

- Naqawī, "Taʾthīr-i qīyāmhā-yi ʿalawīyān", p. 141.

- Dhahabī, Siyar aʿlām al-nubalāʾ, vol. 11, p. 236; Ibn Kathīr, al-Bidāya wa l-nihāya, vol. 10, p. 275–279; Ibn khaldūn. al-ʿIbar, vol. 2, p. 272; Suyūṭī, Tārīkh al-khulafāʾ, p. 363.

- "Item #13113 Abbasid (Medieval Islam), al-Ma'mun (AH 194–218), Silver dirham, 204AH, Isfahan mint , with Ali ibn Musa al-Rida as heir, Album 224".

- Suyūṭī, Tārīkh al-khulafāʾ, p. 364.

- "Disputations on 'the Necessity of Imamate' in the Mu'tazilite Political Theory" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. Burleigh Press. pp. 161–170.

- According to Madelung the unexpected death of the Alid successor, "whose presence would have made any reconciliation with the powerful ʿAbbasid opposition in Baghdad virtually impossible, must indeed arouse strong suspicion that Ma'mun had had a hand in the deaths."

- Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Iraḳ. AMS Press. pp. 190–197.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E., ed. (1987). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXII: The Reunification of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate: The Caliphate of al-Maʾmūn, A.D. 813–33/A.H. 198–213. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-058-8.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2006). When Baghdad Ruled the Muslim World: The Rise and Fall of Islam's Greatest Dynasty. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306814808.

- Cooperson, Michael (2005). Al Ma'mun. Makers of the Muslim world. Oxford: Oneworld. ISBN 978-1851683864.

- Daniel, Elton L. (1979). The Political and Social History of Khurasan under Abbasid Rule, 747–820. Minneapolis & Chicago: Bibliotheca Islamica, Inc. ISBN 978-0-88297-025-7.

- El-Hibri, Tayeb (1999). "Al-Maʾmūn: the heretic Caliph". Reinterpreting Islamic Historiography: Hārūn al-Rashı̄d and the Narrative of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–142. ISBN 0-521-65023-2.

- El-Hibri, Tayeb (2010). "The empire in Iraq, 763–861". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 269–304. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Fishbein, Michael, ed. (1992). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXI: The War Between Brothers: The Caliphate of Muḥammad al-Amīn, A.D. 809–813/A.H. 193–198. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1085-1.

- Gabra, Gawdat (2003). "The Revolts of the Bashmuric Copts in the Eighth and Ninth Centuries". In W. Beltz (ed.). Die koptische Kirche in den ersten drei islamischen Jahrhunderten. Institut für Orientalistik, Martin-Luther-Universität. pp. 111–119. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- John Bagot Glubb The Empire of the Arabs, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1963.

- Ibn al-Sāʿī (2017). Consorts of the Caliphs: Women and the Court of Baghdad. Translated by Shawkat M. Toorawa. Introduction by Julia Bray, Foreword by Marina Warner. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-0477-1.

- E. de la Vaissière, Samarcande et Samarra. Elites d'Asie centrale dans l'empire Abbasside, Peeters, 2007 Archived 16 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Dimitri Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic culture: the Graeco-Arabic translation movement in Baghdad and early Abbasid society Routledge, London, 1998

- Hugh N. Kennedy, The Early Abbasid Caliphate, a political History, Croom Helm, London, 1981

- Kennedy, Hugh (2023). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (2nd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-36690-2.

- John Nawas, A Reexamination of three current explanations for Al-Ma’mun's introduction of the Mihna, International Journal of Middle East Studies 26, (1994) pp. 615–629

- John Nawas, The Mihna of 218 A.H./833 A.D. Revisited: An Empirical Study, Journal of the American Oriental Society 116.4 (1996) pp. 698–708

- Nawas, John Abdallah (2015). Al-Maʼmūn, the Inquisition, and the Quest for Caliphal Authority. Atlanta, Georgia: Lockwood Press. ISBN 978-1-937040-55-0.

- Rekaya, M. (1991). "al-Maʾmūn". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VI: Mahk–Mid (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 331–339. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Bosworth, C. E., ed. (1991). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXIII: Storm and Stress Along the Northern Frontiers of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate: The Caliphate of al-Muʿtasim, A.D. 833–842/A.H. 218–227. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0493-5.

- Kan, Kadir (2012). "Vâsiḳ-Billâh". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 42 (Tütün – Vehran) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 548–549. ISBN 978-975-389-737-2.

- Peter Tompkins, "Secrets of the Great Pyramid", chapter 2, Harper and Row, 1971.

- Turner, John P. (2013). "al-ʿAbbās b. al-Maʾmūn". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_24639. ISSN 1873-9830.

External links

- (in English) Al-Mamum: Building an Environment for Innovation

- Berggren, Len (2007). "Maʾmūn: Abū al‐ʿAbbās ʿAbdallāh ibn Hārūn al‐Rashīd". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. p. 733. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)