al-Mu'tazz

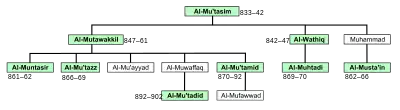

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar (Arabic: أبو عبد الله محمد بن جعفر; 847 – 16 July 869), better known by his regnal title al-Muʿtazz bi-ʾllāh (المعتز بالله, "He who is strengthened by God") was the Abbasid caliph from 866 to 869, during a period of extreme internal instability within the Abbasid Caliphate, known as the "Anarchy at Samarra".

| al-Mu'tazz المعتز | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caliph Commander of the Faithful | |||||

| |||||

| 13th Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 25 January 866 — 13 July 869 | ||||

| Predecessor | al-Musta'in | ||||

| Successor | al-Muhtadi | ||||

| Born | c. 847 Samarra, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Died | July/August 869 (aged 22) Samarra, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Consort | Fatimah Khatun bint al-Fath ibn Khaqan | ||||

| Issue | Abdallah ibn al-Mu'tazz | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | ||||

| Father | al-Mutawakkil | ||||

| Mother | Qabiha | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Originally named as the second in line of three heirs of his father al-Mutawakkil, al-Mu'tazz was forced to renounce his rights after the accession of his brother al-Muntasir, and was thrown in prison as a dangerous rival during the reign of his cousin al-Musta'in. He was released and raised to the caliphate in January 866, during the civil war between al-Musta'in and the Turkish military of Samarra. Al-Mu'tazz was determined to reassert the authority of the caliph over the Turkish army but had only limited success. Aided by the vizier Ahmad ibn Isra'il, he managed to remove and kill the leading Turkish generals, Wasif al-Turki and Bugha al-Saghir, but the decline of the Tahirids in Baghdad deprived him of their role as a counterweight to the Turks. Faced with the assertive Turkish commander Salih ibn Wasif, and unable to find money to satisfy the demands of his troops, he was deposed and died of ill-treatment a few days later, on 16 July 869.

His reign marks the apogee of the decline of the Caliphate's central authority, and the climax of centrifugal tendencies, expressed through the emergence of the autonomous dynasties of the Tulunids in Egypt and the Saffarids in the East, Alid uprisings in Hejaz and Tabaristan, and the first stirrings of the great Zanj Rebellion in lower Iraq.

Early life

The future al-Mu'tazz was born to the Caliph al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861) from his favourite slave concubine, Qabiha.[1] In 849, al-Mutawakkil arranged for his succession, by appointing three of his sons as heirs and assigning them the governance and proceeds of the empire's provinces: the eldest, al-Muntasir, was named first heir, and received Egypt, the Jazira, and the proceeds of the rents in the capital, Samarra; al-Mu'tazz was charged with supervising the domains of the Tahirid governor in the East; and al-Mu'ayyad was placed in charge of Syria.[2] However, over time the favour of al-Mutawakkil shifted towards al-Mu'tazz. Encouraged by his favorite advisor, al-Fath ibn Khaqan, and the vizier Ubayd Allah ibn Yahya ibn Khaqan, the Caliph began contemplating naming al-Mu'tazz as his first heir, and excluding al-Muntasir from the succession. The rivalry between the two princes reflected tensions in the political sphere, as al-Mu'tazz's succession appears to have been backed by the traditional Abbasid elites as well, while al-Muntasir was backed by the Turkish and Maghariba guard troops.[3][4]

In October 861, the Turkish commanders began a plot to assassinate the Caliph. They were soon joined, or at least tacitly supported, by al-Muntasir, whose relations with his father deteriorated rapidly. On 5 December, al-Muntasir was bypassed in favor of al-Mu'tazz for leading the Friday prayer at the end of Ramadan, at the end of which his father's advisor al-Fath and the vizier Ubayd Allah demonstratively kissed his hands and feet, before accompanying him on the return to the palace; and on 9 December al-Mutawakkil, among other humiliations inflicted on him, threatened to kill his eldest son.[5][6] As a result, on the night of 10/11 December, the Turks killed al-Mutawakkil and al-Fath, and al-Muntasir became caliph.[7][8] Almost immediately, al-Muntasir sent for his brothers to come and give the oath of allegiance (bay'ah) to him.[9] Thus, when the vizier Ubayd Allah, upon being informed of al-Mutawakkil's death, went to the house of al-Mu'tazz, he did not find him there; and when his supporters, including the abna al-dawla and others and numbering several thousand, gathered in the morning and urged him to storm the palace, he refused, with the words "our man is in their hands".[10] The murder of al-Mutawakkil began the tumultuous period known as "Anarchy at Samarra", which lasted until 870 and brought the Abbasid Caliphate to the brink of collapse.[11]

Pressured by the Turkish commanders Wasif al-Turki and Bugha al-Saghir, both al-Mu'tazz and al-Mu'ayyad renounced their places in the succession on 27 April 862.[12] However, al-Muntasir died in June 862, without having named any new heir.[13] The Turks now strengthened their hold over the government and selected a cousin of al-Muntasir, al-Musta'in (r. 862–866), as the new caliph.[13] The new caliph was almost immediately faced with a large riot in Samarra in support of al-Mu'tazz; the rioters included not only the "market rabble" but also mercenaries from the Shakiriyya troops. The riot was down by the Maghariba and Ushrusaniyya regiments, but casualties on both sides were heavy.[14] Al-Musta'in, worried that al-Mu'tazz or al-Mua'yyad could press their claims to the caliphate, first attempted to buy them off by offering them an annual subsidy of 80,000 gold dinars. Shortly after, however, their properties were confiscated—according to al-Tabari, that of al-Mu'tazz was valued at ten million dirhams—and imprisoned under the auspices of Bugha al-Saghir in one of the rooms of the Jawsaq Palace.[15]

Caliphate

Rivalries between the Turkish leaders led to a split in 865, when al-Musta'in, Wasif, and Bugha left Samarra for Baghdad, where they arrived on 5/6 February 865. There they were joined by many of their followers, and allied with the city's Tahirid governor, Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Tahir, who began fortifying the city. The bulk of the Turks, however, remained in Samarra. Their position was threatened by this coalition, so they released al-Mu'tazz and proclaimed him caliph. On 24 February, al-Mu'tazz placed his brother Abu Ahmad (the future al-Muwaffaq) in charge of the army, and sent him to lay siege to Baghdad.[16][17][18] Abu Ahmad played a leading role in the siege, which created a close and lasting relationship with the Turkish military, that would later allow him to emerge as the virtual regent of the caliphate alongside his brother al-Mu'tamid (r. 870–892).[19]

The siege dragged on until December 865, when a combination of privations, lack of money to pay its supporters, and the price hikes caused by the siege eroded support for al-Musta'in's regime. As a result, Muhammad ibn Tahir opened negotiations with the besiegers, and a settlement was reached, which amounted to a mutual compromise over the sharing of the empire's proceeds: the Turks and other troops of Samarra received two-thirds of annual state revenue, while the remainder would go to Ibn Tahir and his Baghdad forces. As part of the agreement, al-Musta'in would abdicate, in exchange for an annual pension of 30,000 dinars.[20] Thus on 25 January 866, after the surrender of Baghdad, al-Mu'tazz became officially the sole, legitimate caliph.[1]

Although he was placed on the throne by the Turks, al-Mu'tazz proved a capable ruler and was determined to restore the authority and independence of his office.[21] He appointed as his vizier Ahmad ibn Isra'il, who had formerly served as his secretary during al-Mutawakkil's reign.[1][22] Al-Mu'tazz moved quickly to sideline any potential rivals. Thus, despite his pledge of safety to al-Musta'in, in October/November 866 al-Mu'tazz had his predecessor assassinated at al-Katul in Samarra.[1] In the same way he had his younger brother al-Mu'ayyad executed, even after forcing him to again renounce his rights to succession.[1] Finally, Abu Ahmad, although initially welcomed with much honor by the Caliph for his role in winning the civil war, was also imprisoned along with al-Mu'ayyad. However, his support from the military saved his life. He was eventually released and sent to Basra before being allowed to settle in Baghdad.[23] The Caliph then targeted the powerful Turkish commanders Wasif al-Turki and Bugha al-Saghir. The first move against them in late 866 failed due to the opposition of the army, and the two men were restored to their posts.[24] In the next year, however, Wasif was killed by Turkish troops that had mutinied demanding the payment of their arrears, while Bugha was imprisoned and executed on the Caliph's orders in 868. Another powerful Turkish commander, Musa ibn Bugha al-Kabir, was effectively exiled to Hamadan at the same time.[21][25]

Despite these successes, the Caliph could not overcome the main problem of the period: a shortage of revenue with which to pay the troops. The financial straits of the Caliphate had become evident already at his accession—the customary accession donative of ten months' pay for the troops had to be reduced to two for lack of funds—and had helped bring down the regime of al-Musta'in in Baghdad.[20] The civil war and the ensuing general anarchy only worsened the situation, as revenue stopped coming in even from the environs of Baghdad, let alone more remote provinces.[26] As a result, al-Mu'tazz refused to honor his agreement with Ibn Tahir in Baghdad, leaving him to provide for his own supporters; this led to unrest in the city and the rapid decline of Tahirid authority.[27] The turmoil in Baghdad was worsened by al-Mu'tazz, who in 869 dismissed Ibn Tahir's brother and successor Ubaydallah, and replaced him with his far less capable brother Sulayman.[28] In the event, this only served to deprive the Caliph of a useful counterweight against the Samarra soldiery and allowed the Turks to regain their former power.[21]

As a result, by 869 the Turkish leaders Salih ibn Wasif (the son of Wasif al-Turki) and Ba'ikbak were again in the ascendant and secured the removal of Ahmad ibn Isra'il.[28] Finally, unable to meet the financial demands of the Turkish troops, in mid-July a palace coup deposed al-Mu'tazz. He was imprisoned and maltreated to such an extent that he died after three days, on 16 July 869.[28] He was succeeded by his cousin al-Muhtadi.[28]

Legacy

Despite his efforts to strengthen his position and restore control over the military, al-Mutazz's reign is marked by instability and insecurity, and by his ultimate failure to subdue the military. This weakness in the center fed the centrifugal tendencies already evident in the Caliphate's provinces.[28] In Egypt, the talented Turkish commander Ahmad ibn Tulun was appointed governor in 868 and proceeded to establish the autonomous Tulunid dynasty. Although it fell to the Abbasids in 905, the Tulunid regime had established Egypt as a distinct political entity for the first time since the Pharaohs. Restored Abbasid rule proved volatile; another local dynasty, the Ikhshidids, took power in 935, followed by the country's conquest by the Abbasids' rivals, the Fatimid Caliphate, in 969.[29] In the east, Alid uprisings weakened Tahirid rule, and led to the establishment of a Zaydi state in Tabaristan, under Hasan ibn Zayd. At the same time, Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar began his assault on the waning Tahirids, which would lead him to control over the eastern provinces of the Caliphate, and even an unsuccessful attempt to seize the caliphal throne itself in 876.[28][30] Closer to home, Kharijite revolts shook the Jazira to the north, and in the south, around Basra, the first stirrings of the great Zanj Rebellion began.[28]

References

- Bosworth 1993, p. 793.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 167.

- Gordon 2001, p. 82.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 169.

- Kraemer 1989, pp. 171–173, 176.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 168–169.

- Kraemer 1989, pp. 171–182, 184, 195.

- Kennedy 2006, pp. 264–267.

- Kraemer 1989, pp. 197–199.

- Kraemer 1989, pp. 182–183.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 169–173.

- Kraemer 1989, pp. 210–213.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 171.

- Saliba 1985, pp. 3–5.

- Saliba 1985, pp. 6–7.

- Saliba 1985, pp. 28–44.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 135.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 171–172.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 149ff..

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 138–139.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 172.

- Kraemer 1989, p. 164.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 149.

- Saliba 1985, pp. 122–124.

- Bosworth 1993, pp. 793–794.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 138.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 139.

- Bosworth 1993, p. 794.

- Bianquis 1998, pp. 86–119.

- Bosworth 1975, pp. 102–103, 108ff..

Sources

- Bianquis, Thierry (1998). "Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Ṭūlūn to Kāfūr, 868–969". In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume One: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–119. ISBN 978-0-521-47137-4.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1975). "The Ṭāhirids and Ṣaffārids". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–135. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1993). "al-Muʿtazz Bi'llāh". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VII: Mif–Naz (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 793–794. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2006). When Baghdad Ruled the Muslim World: The Rise and Fall of Islam's Greatest Dynasty. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306814808.

- Kraemer, Joel L., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXIV: Incipient Decline: The Caliphates of al-Wāthiq, al-Mutawakkil and al-Muntaṣir, A.D. 841–863/A.H. 227–248. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-874-4.

- Saliba, George, ed. (1985). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXV: The Crisis of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate: The Caliphates of al-Mustaʿīn and al-Muʿtazz, A.D. 862–869/A.H. 248–255. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-883-7.