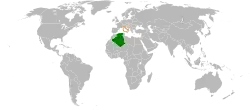

Algeria–Holy See relations

Relations between Algeria and the Holy See have been tensions in the relationship in recent years due to criticism of the Algerian government by the Vatican[1] and increasing restrictions imposed on Algerian Catholics.[2]

| |

Algeria |

Holy See |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Algerian Embassy, Vatican City | Apostolic Nunciature, Algiers |

Algerian independence

Prior to independence, Algeria was home to a million Catholic settlers (10%).[3] During the Algerian War of 1954-1962 the Holy See accepted the occupation of Algeria by the French colonial empire, and did not speak out in favor of Algerian independence[4] despite pleas from the Algerian rebels to mediate.[5] After Algeria became independent most of the French settlers left the country. However, Algeria generally retained close relationships with France, maintained diplomatic ties with the Holy See and allowed Roman Catholic priests to continue ministering to the remaining Catholics in Algeria.[6]

Official relationship

Although Islam is the state religion of Algeria, the Holy See has maintained a comparatively good relationship with the Algerian authorities, with Léon-Étienne Duval being famously recognized as the bishop of Muslims after the departure of French colonists.[7]

The Algerian state has sought to clearly distinguish between the Catholic religion, which is licit in Algeria with limitations to proselytism, and between Evangelical sects, which are officially forbidden and legally repressed by state powers. However, since a 2006 law limited religious worship to government-approved buildings, more than a dozen Catholic churches have been closed, and several priests have been jailed under new provisions that call for a more strict application of Islamic law.[2]

Recent events

In 1996, seven Cistercian monks were killed by Islamist extremists, followed by the death of Roman Catholic bishop Pierre Claverie when a bomb exploded at his residence.[8] Details of the deaths are still disputed by the Vatican.[9] Concerned by mounting violence, the Vatican issued a harsh criticism of the government handling of the crisis in September 1997, saying that "for too long, the international community has looked on with detachment at the tragedy that is systematically bloodying" Algeria.[10] On January 8, 1998, the Vatican's official daily newspaper called upon the international community to help bring an end to the "genocide" in Algeria.[11]

On the death of Pope John Paul II in April 2005, the president of Algeria Abdelaziz Bouteflika attended the funeral.[12]

Following remarks by Pope Benedict XVI in Regensberg on 12 September 2006 which were widely interpreted as being offensive to the Muslim religion, the Foreign Affairs minister asked the Vatican's ambassador to provide explanations of these statements.[13] The Algerian Association of Koranic Doctors called on Muslim countries to withdraw their ambassadors from Vatican City in protest.[14]

In March 2017 Pope Francis appointed White Fathers missionary M. Afr. John MacWilliam as bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Laghouat, covering the largely Saharan inland of Algeria. MacWilliaam had risen to the rank of major in the British army through 18 years of service, was ordained a priest in 1991,[15] and joined the White Fathers after the assassination of four of its members in Tizi Ouzou, Algeria. He had become known for his efforts at building bridges with the Muslim community.[16]

See also

References

- "Pope speaks out on Algeria and Iraq". BBC News. 1998-01-11. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "Growing Persecution in Algeria and Egypt". Catholic Online. 2008-07-13. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- Greenberg, Udi; A. Foster, Elizabeth (2023). Decolonization and the Remaking of Christianity. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 105. ISBN 9781512824971.

- Marnia Lazreg (2007). Torture and the twilight of empire: from Algiers to Baghdad. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13135-1.

- Paul Hofmann (March 12, 1958). "Algerians Appeal to Vatican; New Peace Bid Made to Paris". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- Alistair Horne (1978). A savage war of peace: Algeria, 1954-1962. Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-61964-7.

- Desmond O'Grady (Jan 31, 1997). "A tale of two prelates: an ecumenist & a schismatic". Commonweal. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "French Bishop Killed By Bomb in Algeria". New York Times. August 2, 1996. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "Vatican urges truth over French monks slain in Algeria in 1996". La Stampa. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "U.N., Vatican Condemn Massacres in Algeria; Atrocities Intensify in Six-Year Civil War". The Washington Post. September 9, 1007. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "Vatican seeks foreign action in Algeria". The Indian Express. 1998-01-09. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "Address of His Holiness Benedict XVI to H.E. Mr Idriss Jazaïy, Ambassador of Algeria". Vatican. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "The Foreign Affairs Ministry sends for the Vatican's ambassador". Algeria-Events. Sep 18, 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "Two churches struck in Nablus as Muslim countries criticize pope". Asia News. 2006-09-16. Archived from the original on 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- Connolly, Marshall. "Pope Francis appoints peacemaking soldier as bishop over desert diocese that spans two million square kilometers". Catholic Online. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- "British soldier turned priest who risked life to keep Catholic church alive in Algeria to become a bishop". www.thetablet.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-08.