Eight-Nation Alliance

The Eight-Nation Alliance was a multinational military coalition that invaded northern China in 1900 with the stated aim of relieving the foreign legations in Beijing, which was being besieged by the popular Boxer militia, who were determined to remove foreign imperialism in China. The allied forces consisted of about 45,000 troops from the eight nations of Germany, Japan, Russia, Britain, France, the United States, Italy, and Austria-Hungary. Neither the Chinese nor the quasi-concerted foreign allies issued a formal declaration of war.[1]

| Eight-Nation Alliance | |

|---|---|

| 八國聯軍 (in Chinese) | |

The eight nations with their naval ensigns, from top to bottom, left to right: | |

| Active | 10 June 1900 – 7 September 1901 (455 days) |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | None (individual) |

| Type | Expeditionary force |

| Role | To relieve a siege of various legations, suppress the Boxer Rebellion, and safeguard privileges of foreign nationals and Chinese Christians. |

| Size | About 51,755 troops |

| Nickname(s) | Coalition |

| Engagements | Boxer Rebellion |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Second: First: |

| Eight Nations Alliance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 八國聯軍 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 八国联军 | ||||||

| |||||||

No treaty or formal agreement bound the alliance together. Some western historians define the first phase of hostilities, starting in August 1900, as "more or less a civil war",[1] though the Battle of the Taku Forts in June pushed the Qing government to support the Boxers. With the success of the invasion, the later stages developed into a punitive expedition, which pillaged Beijing and North China for more than a year. The fighting ended in 1901 with the signing of the Boxer Protocol.[2]

History

Background

The Boxers, a peasant movement, had attacked and killed foreign missionaries, nationals, and Chinese Christians across northern China in 1899 and 1900. The Qing government and its Imperial Army supported the Boxers and, under the Manchu general Ronglu, besieged foreign diplomats and civilians taking refuge in the Legation Quarter in Beijing (then romanized as Peking).[3]

The diplomatic compound was under siege by the Wuwei Rear Division of the Chinese Army and some Boxers (Yihetuan), for 55 days, from 20 June to 14 August 1900. A total of 473 foreign civilians, 409 soldiers from eight countries, and about 3,000 Chinese Christians took refuge in the Legation Quarter.[4] Under the command of the British minister to China, Claude Maxwell MacDonald, the legation staff and security personnel defended the compound with small arms and one old cannon discovered and unearthed by Chinese Christians, who turned it over to the allies. It was nicknamed the International Gun because the barrel was British, the carriage Italian, the shells Russian and the crew American.[5]

Also under siege in Beijing was the North Cathedral, the Beitang of the Catholic Church. The Beitang was defended by 43 French and Italian soldiers, 33 foreign Catholic priests and nuns, and about 3,200 Chinese Catholics. The defenders suffered heavy casualties from lack of food and Chinese mines that exploded in tunnels dug beneath the compound.[6]

On 14 August 1900, the allies marched to Beijing from Tianjin to relieve the Legation Quarter siege.[7]

Military engagement, punitive expeditions and looting

The allied troops invaded and occupied Beijing on 14 August 1900. They defeated the Qing Imperial Army's Wuwei Corps in several engagements and quickly brought an end to the siege and also the Boxer Rebellion. Empress Dowager Cixi, the emperor and high government officials fled the Imperial Palace for Xi'an and sent Li Hongzhang for peace talks with the alliance.[8]

As allied troops moved from Beijing into the North China countryside, they executed unknown numbers of people accused or suspected of being or resembling Boxer rebels, which became the subject of an early short film.[9] A U.S. Marine wrote that he witnessed German and Russian troops raping and then bayoneting women.[10] While the allies were in Beijing, they looted the palaces, yamens, and government buildings inflicting incalculable loss of cultural relics, books on literature and history (including the famous Yongle Dadian) and damage to cultural heritage (including the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace, Xishan and the Old Summer Palace).[2][11]

More than 3,000 gold-plated bronze Buddhas, 1,400 artistic products and 4,300 bronzes in Songzhu Temple (嵩祝寺) were looted. The gold plating on the copper tanks in front of the Forbidden City palaces was scraped off by allied troops, leaving scratch marks that can be seen even now. The Yongle Dadian that was compiled by 2,100 scholars during the Ming Yongle period (1403–1408), with a total of 22,870 volumes, was partially destroyed in the Second Opium War in 1860. Later, it was collected in the Imperial Palace on Nanchizi Street. It was found and destroyed completely by the alliance in 1900. Part of the Yongle Dadian was used for the construction of fortifications.[2][12]

The Complete Library of the Four Treasuries (or Siku Quanshu) was compiled by 360 scholars during the Qing Qianlong period. It collected 3,461 ancient books, totaling 79,309 volumes. The whole book consisted of seven sets. One set was destroyed in 1860 during the Second Opium War. Another 10,000 plus volumes were destroyed in 1900 by the Eight-Nation Alliance. The Hanlin Academy houses a collection of precious books, orphans, books of the Song dynasty, literature and history materials, and precious paintings. The Eight-Nation Alliance looted the collections. Some of these looted books remain in the custody of museums in London and Paris.[2][13]

Member nations

| Forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance Relief of the Legations _that_fought_against_the_Boxer_Rebellion_in_China%252C_1900._From_the_left_Britain%252C_United_States%252C_Australia%252C_India%252C_Germany%252C_France%252C_Austria-Hungary%252C_Italy%252C_Japan._(49652330563).jpg.webp) Troops of the Eight-Nation Alliance in 1900 (Russia excepted); left to right: Britain, United States, Australia, India, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Japan | |||

| Countries | Warships (units) |

Marines (men) |

Army (men) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 540 | 20,300 | |

| 10 | 750 | 12,400 | |

| 8 | 2,020 | 10,000 | |

| 5 | 390 | 3,130 | |

| 2 | 295 | 3,125 | |

| 5 | 600 | 300 | |

| 2 | 80 | 2,500 | |

| 4 | 296 | unknown | |

| Total | 54 | 4,971 | 51,755 |

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary had a single cruiser, SMS Zenta, on station at the beginning of the rebellion, based at the Russian concession of Port Arthur.[14] Detachments of sailors from the Zenta were the only Austro-Hungarian forces to see action.[15] Some were involved in defending the legations under siege, and another detachment was involved in the rescue attempts.[15]

In June, the Austro-Hungarians helped hold the Tianjin railway against Boxer forces and fired upon several armed junks on the Hai River near Tongzhou in Beijing. They took part in the seizure of the Taku Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by Capt. Roger Keyes of HMS Fame.

The Austro-Hungarian Navy sent the cruisers SMS Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia, SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth, SMS Aspern and a company of marines to China. Arriving in September they were too late since most of the fighting had ended, and the legations had been relieved. The cruisers and the Zenta were involved in the shelling and capture of several Chinese forts.[15] The Austro-Hungarians suffered minimal casualties during the rebellion. After the Boxer Uprising, a cruiser was maintained permanently on the Chinese coast, and a detachment of marines was deployed at the Austro-Hungarian embassy in Beijing.[15] Lieutenant Georg Ludwig von Trapp, made famous in the 1959 musical The Sound of Music, was decorated for bravery aboard SMS Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia during the rebellion.[16][17]

British Empire

At the outset of the Boxer Rebellion, Britain was engaged in the Second Boer War in South Africa.[18] Consequently, with the army tied down by the war, the British had to rely on the China Squadron and troops largely from India. The Royal Navy's China Squadron, stationed off Tianjin, consisted of the battleships Barfleur and Centurion, the cruisers Alacrity, Algerine, Aurora, Endymion, and Orlando, and the destroyers Whiting and Fame.[19]

British forces were the third-largest contingent in the alliance and consisted of the following units: Naval Brigade, 12th Battery Royal Field Artillery, Hong Kong & Singapore Artillery, 2nd Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers, 1st Bengal Lancers, 7th Rajput Infantry, 24th Punjab Infantry, 1st Sikh Infantry, Hong Kong Regiment, 1st Chinese Regiment, Royal Engineers, and other support personnel.[20][21]

Australian colonies

The Australian colonies did not become a unified federation until 1901. As such, several of the colonies, independently of each other, sent contingents of naval and army personnel to support the British contingent. For example, South Australia sent its entire navy: the gunboat HMCS Protector.[22] Australia was not an official member of the Eight-Nation Alliance, and its forces arrived too late to see significant action.[23]

India

Britain provided 10,000 troops, many of whom were Indian troops, made out of units of Baluchis, Sikhs, Gurkhas, Rajputs and Punjabis.[24][25][26]

Germany

Germany had gained a presence in China after the Juye Incident in which two German missionaries had been murdered in November 1897. The concession in Jiaozhou Bay, with the port of Qingdao, was used as a naval base for the East Asia Squadron and a trading port. The German concession was governed and garrisoned by the Imperial German Navy. At the outbreak of the Boxer Rebellion in June 1900, the garrison of the concession was composed of the III. Seebataillon, with 1,126 men, a marine/naval artillery battery, about 800 men of a Kommando Detachment and sailors from the East Asian Squadron.[27]

With the increasing threat of the Boxers, a small armed group from the III. Seebatallion was sent to Beijing and Tianjin to protect German interests there while the majority of the remaining forces stayed behind to prevent attacks against Qingdao. The siege of the foreign legations in Beijing soon convinced Germany and the other European powers that more forces were needed to be sent to China to reinforce the allied forces. The first troops dispatched from Germany were the marine-Expeditionskorps which consisted of the I. and II. Seebatallions.[27]

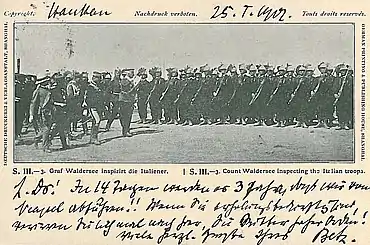

They were soon followed by the Ostasiatisches Expeditionskorps (East Asian Expeditionary Corps), which was a force of about 15,000 of mostly volunteers from the regular Army under the command of General Alfred Count von Waldersee. It comprised initially four and later six two-battalion infantry regiments and a jäger company, single regiments of cavalry and field artillery and various support and logistics units.[27] On arrival in China, it incorporated the marine-Expeditionskorps that had preceded it to China by a few weeks.[27]

Most of the German forces arrived too late to take part in any of the major actions.[27] The first elements of the Expeditionskorps arrived at Taku on September 21,[27] after the legations had been relieved. As a result, most of the Expeditionskorps was mainly employed for garrison duties. They fought a number of smaller engagements against pockets of remaining Boxers.[28] The Expeditionskorps was disbanded and recalled to Germany in early 1901.[28]

France

Three battalions of marines, the II/9th, and the I and II/11th RIMa which were stationed in French Indochina were sent to China. They joined the 1st Brigade commanded by General Henri-Nicolas Frey. In July 1900, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of infantry embarked from Toulon but did not reach China until September. In October, following losses and rotations of duty, the first three battalions sent were included in the 16th regiment of marines by order of General Régis Voyron, commander in chief of the French Expeditionary Corps in China. On 1 January 1901, the 16th RIMa was renamed the 16th Regiment of colonial infantry. At the end of the campaign, it moved to a new base in Tianjin, with its headquarters in the former buildings of the Chinese admiralty.[29]

Italy

In 1898, the Italians had demanded San Mun Bay as a concession, but the Chinese refused.[30] The Italian Navy then dispatched a squadron to San Mun Bay, but no further action was taken. The squadron remained there, and in the summer of 1900, when the Boxer Rebellion broke out, detachments from Italian cruisers were sent to Beijing. Italian forces were initially made up of sailors from warships.[31] Some of them helped the French defend the Pei Tang Catholic cathedral, and another defended the European Legations in Beijing during the 55-day siege.[30] Italian sailors also took part in the attacks on the Taku forts and in capturing Tianjin.[30]

A larger contingent was later dispatched from Italy, including 83 officers, 1,882 troops, and 178 horses. The contingent included a battalion of Bersaglieri, which was formed from one company each from the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, and 11th Bersaglieri Regiments. In addition, the 24th Line Regiment, volunteers from the Alpini, a battery of machine guns, and some engineers were also sent to China.[31] A battery of field guns was also supplied by the Italian Navy.[31] The total force of 1,965 officers and men, which composed the Italian expeditionary force against the Boxers, was officially referred to as the Italian Royal Troops in China.[30] In August 1900, when the larger force reached the capital, the Italians had seven cruisers and 2,543 men in the country. They were involved in numerous operations along the coast and in the interior of northern China.[30]

The larger part of the approximately 2,000 Italian soldiers and officers who fought in the campaign against the Boxers were recalled from Beijing after the end of the conflict. Italy obtained a 151-acre concession area in Tianjin and the right to occupy the Shanhai Pass fort.[32][30] A small naval squadron and a naval garrison were maintained in China to protect Italian interests there.[30]

Japan

Japan provided the largest contingent of troops; 20,840, as well as 18 warships. Of the total number, 20,300 were Imperial Japanese Army troops of the 5th Infantry Division under Lieutenant General Yamaguchi Motomi; the remainder were 540 naval rikusentai (Marines) from the Imperial Japanese Navy.

At the beginning of the Boxer Rebellion, the Japanese had only 215 troops in northern China stationed at Tianjin, nearly all of whom were naval rikusentai from the Kasagi and the Atago, under the command of Captain Shimamura Hayao.[33] The Japanese were able to contribute 52 men to the Seymour Expedition.[33] On 12 June the advance of the Seymour Expedition was halted some 30 miles from the capital, by mixed Boxer and Chinese regular army forces. The vastly-outnumbered allies withdrew to the vicinity of Tianjin and had suffered more than 300 casualties.[34]

The army general staff in Tokyo had become aware of the worsening conditions in China and had drafted ambitious contingency plans,[35] but the government, in the wake of the Triple Intervention five years earlier, refused to deploy a large contingent of troops unless it was requested by the western powers.[35] However, three days later a provisional force of 1,300 troops, commanded by Major General Fukushima Yasumasa, was deployed to northern China. Fukushima was chosen because he spoke English, which enabled him to communicate with the British commander. The force landed near Tianjin on 5 July.[35]

On 17 June naval Rikusentai from the Kasagi and Atago had joined British, Russian and German sailors to seize the Taku forts, near Tianjin.[35] The British, in light of the precarious situation, were compelled to ask Japan for additional reinforcements since the Japanese had the only readily available forces in the region.[35] Britain at the time was heavily engaged in the Boer War, and so much of the British Army was tied down in South Africa. In addition, deploying large numbers of troops from its garrisons in India would take too much time and weaken internal security there.[35]

Overriding personal doubts, Foreign Minister Aoki Shūzō calculated that the advantages of participating in an allied coalition were too attractive to ignore. Prime Minister Yamagata likewise concurred, but others in the cabinet demanded that guarantees from the British in return for the risks and costs of the major deployment of Japanese troops.[35] On 6 July the 5th Infantry Division was alerted for possible deployment to China, but no timetable was set for its deployment. On 8 July, with more ground troops urgently needed to lift the siege of the foreign legations at Beijing, the British ambassador offered the Japanese government one million pound sterling in exchange for Japanese participation.[35]

Shortly afterward, advance units of the 5th Division departed for China, bringing Japanese strength to 3,800 members of the 17,000-strong allied force.[35] The commander of the 5th Division, Lieutenant General Yamaguchi Motoomi, had taken operational control from Fukushima. Japanese troops were involved in the storming of Tianjin on 14 July,[35] and the allies later consolidated and awaited the remainder of the 5th Division and other coalition reinforcements. The siege of legations was lifted on 14 August; the Japanese force of 13,000 was the largest single contingent, making up about 40% of the approximately 33,000-strong allied expeditionary force.[35]

Japanese troops involved in the fighting had acquitted themselves well although a British military observer felt that their aggressiveness, densely-packed formations, and overly aggressive attacks cost them excessive and disproportionate casualties.[36] For example, during the Tianjin fighting, the Japanese suffered more than half of the allied casualties, 400 out of 730, but made up less than one quarter (3,800) of the force of 17,000.[36] Similarly at Beijing, the Japanese accounted for almost two thirds of the losses, 280 of 453, but constituted slightly less than half of the assault force.[36]

Russia

Russia supplied the second largest force, after Japan, with 12,400 troops consisting mainly of garrisons from Port Arthur and Vladivostok.[37] On 30 November 1900, Admiral Yevgeni Ivanovich Alekseyev compelled the Chinese military governor of Shenyang, Zeng Qi, to sign an agreement that effectively ended Chinese sovereignty over Manchuria and placed it under Russian control.[38]

United States

In the United States, the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion was known as the China Relief Expedition.[39] The United States was able to play a major role in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion largely because of the presence of American forces deployed in the Philippines since the U.S. annexation after the Spanish–American War in 1898.[40] Of the foreigners under siege in Beijing, there were 56 American sailors and Marines from the USS Oregon and USS Newark.[40] The main American formations deployed to relieve the siege were the 9th Infantry and 14th Infantry regiments, elements of the 6th Cavalry regiment, the 5th Artillery regiment, and a Marine battalion, all under the command of Colonel Adna Chaffee.[41][42] Herbert Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover were living in the foreign compound during the siege when Mr. Hoover was working for the Chinese Engineering and Mining Company. Mr. Hoover helped erect barricades and formed a protective force of the able-bodied men. Mrs. Hoover helped set up a hospital, nursed the wounded, set up a dairy, took part in the night watch, took tea to sentries and carried a Mauser .38 semi-automatic pistol.[43][44]

See also

Notes

- Klein (2008), p. 3.

- Hevia, James L. "Looting and its discontents: Moral discourse and the plunder of Beijing, 1900–1901" in R. Bickers and R.G. Tiedemann (eds.), The Boxers, China, and the world Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009

- Grant Hayter-Menzies, Pamela Kyle Crossley (2008). Imperial masquerade: the legend of Princess Der Ling. Hong Kong University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-962-209-881-7. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- Thompson, 84–85

- Benjamin R. Beede (1994). The War of 1898, and U.S. interventions, 1898–1934: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 50. ISBN 0-8240-5624-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Thompson, 85, 170–171

- O'Conner, David The Boxer Rebellion London:Robert Hale & Company, 1973, Chap. 16. ISBN 0-7091-4780-5

- Michael Dillon (2016). Encyclopedia of Chinese History. Taylor & Francis. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-317-81716-1.

- Beheading a Chinese Boxer at IMDB

- Robert B. Edgerton (1997). Warriors of the rising sun: a history of the Japanese military. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 80. ISBN 0-393-04085-2. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- 剑桥中国晚清史. 中国社会科学出版社. 1985. ISBN 978-7500407669.

- 剑桥中国晚清史. 中国社会科学出版社. 1985. ISBN 978-7500407669.

- 剑桥中国晚清史. 中国社会科学出版社. 1985. ISBN 978-7500407669.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 139.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 140.

- Carr 2006, p. 224.

- Bassett 2015, p. 393.

- Ion 2014, p. 37.

- Harrington 2001, p. 28.

- Bodin 1979, p. 34.

- Harrington 2001, p. 29.

- Nicholls, B., Bluejackets and Boxers

- "China (Boxer Rebellion), 1900–01". Australian War Memorial. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Krishnan, Ananth (8 July 2011). "The forgotten history of British India troops in China". The Hindu. Beijing. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815–1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-57607-925-6. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Lee Lanning, Colonel Michael (2007). Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, from Ancient Greece to Today#s Private Military Companies. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-307-41604-9. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- de Quesada & Dale 2013, p. 23.

- de Quesada & Dale 2013, p. 24.

- "Insignes des Troupes Françaises en Chine". www.symboles-et-traditions.fr. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Paoletti 2008, p. 280.

- Bodin 1979, p. 29.

- Shirley Ann Smith (2012). Imperial Designs: Italians in China 1900–1947. Lexington Books. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-61147-502-9.

- Ion 2014, p. 44.

- Drea 2009, p. 97.

- Drea 2009, p. 98.

- Drea 2009, p. 99.

- To the Harbin Station: The Liberal Alternative in Russian Manchuria, 1898–1914. Stanford University Press. May 1999. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8047-6405-6.

- G. Patrick March (1996). Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-275-95566-3.

- "Documents of the Boxer Rebellion (China Relief Expedition), 1900–1901". Naval History & Heritage Command. United States Navy. 13 March 2000. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "The Boxer Rebellion and the U.S. Navy, 1900–1901". U.S. Naval History & Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "U.S. Army Campaigns: China Relief Expedition". United States Army Center of Military History. United States Army. 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Plante, Trevor K. (1999). "U.S. Marines in the Boxer Rebellion". Prologue Magazine. United States National Archive. 31 (4). Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Beck Young, Nancy (2004). Lou Henry Hoover: Activist First Lady. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-7006-1357-9.

- Boller, Paul F. Jr. (1988). Presidential Wives. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 271–273. ISBN 0-19-505976-X.

References

- Bassett, Richard (2015). For God and Kaiser: The Imperial Austrian Army, 1619–1918. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17858-6.

- Bodin, Lynn (1979). The Boxer Rebellion. Chris Warner (illustrator). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-335-6.

- Carr, Charmian (2006). Forever Liesl: My the Sound of Music Story. Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-45100-6.

- de Quesada, Alejandro; Dale, Chris (2013). Imperial German Colonial and Overseas Troops 1885–1918. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-165-1.

- Drea, Edward J. (2009). Japan's Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1853–1945. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-8032-1708-9.

- Harrington, Peter (2001). Peking 1900: The Boxer Rebellion. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-181-8.

- Ion, Hamish (2014). "The Idea of Naval Imperialism: The China Squadron and the Boxer Uprising". British Naval Strategy East of Suez, 1900–2000: Influences and Actions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-76967-3.

- Klein, Thoralf (2008). "The Boxer War-the Boxer Uprising". Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. ISSN 1961-9898.

- Paoletti, Ciro (2008). A Military History of Italy (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98505-9.

- Smith, Shirley Ann (2012). Imperial Designs: Italians in China 1900–1947 (illustrated ed.). Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-61147-502-9.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-034-3.

- Thompson, Larry Clinton. William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009.

- Xu, Guangqiu (2012). "Eight Foreign Armies Invasion of China". In Li, Xiaobing (ed.). China at War: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598844153.