Amiral Baudin-class ironclad

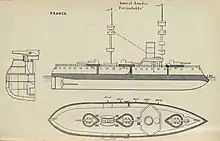

The Amiral Baudin class was a type of ironclad barbette ship of the French Navy built in the late 1870s and late 1880s. The class comprised two ships: Amiral Baudin and Formidable. After the Italian Navy began building a series of very large ironclads in the mid-1870s, public pressure on the French naval command to respond in kind prompted the design for the Amiral Baudin class. New, very large guns were developed to counter the weapons carried by the Italian ships; Amiral Baudin and Formidable were equipped with a main battery of three 370 mm (14.6 in) guns in three open barbettes, all on the centerline. Begun in 1879, work on the ships proceeded slowly and they were not finished until 1888–1889, shortly before the first pre-dreadnought battleships began to be built, which rendered older ironclads like the Amiral Baudin class obsolete.

Formidable in Algiers in 1899 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Amiral Baudin class |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Terrible class |

| Succeeded by | Hoche |

| Built | 1879–1889 |

| In service | 1888–1903 |

| Completed | 2 |

| Retired | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Barbette ship |

| Displacement | 11,720 long tons (11,910 t) |

| Length | 101.4 m (332 ft 8 in) lwl |

| Beam | 21.34 m (70 ft) |

| Draft | 8.46 m (27 ft 9 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Complement | 625 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Amiral Baudin and Formidable served with the Mediterranean Fleet for the bulk of their active careers, Formidable serving as its flagship early in her career. In 1895, both ships were involved in a grounding accident caused by Formidable's failure to conform to the fleet commander's instructions. Both ships were modernized between 1896 and 1898, losing their amidships barbette, which was replaced with an armored battery for new quick-firing guns, among other changes. Both ships were transferred to the Northern Squadron after returning to service, as newer pre-dreadnoughts had entered service by that point, taking their place in the more strategically important Mediterranean Fleet. Both ships were withdrawn from service by 1903, and Amiral Baudin was hulked in 1909. Formidable was broken up two years later, but Amiral Baudin's fate is unknown.

Design

In the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, the French Navy embarked on a construction program to strengthen the fleet in 1872. By that time, the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) had begun its own expansion program under the direction of Benedetto Brin, which included the construction of several very large ironclad warships of the Duilio and Italia classes, armed with 450 mm (17.7 in) 100-ton guns. The French initially viewed the ships as not worthy of concern, though by 1877, public pressure over the new Italian vessels prompted the Navy's Conseil des Travaux (Board of Construction) to design a response, the first of which was the barbette ship Amiral Duperré.[1]

Further pressure was placed on the French naval command by developments in very large guns abroad. In addition to the Italian 100-ton guns, the British Royal Navy was experimenting with 81-ton guns, the British firm Armstrong (which had developed the 100-ton gun) was designing a 160-ton gun, and the German firm Krupp was rumored to be working on a colossal 220-ton gun. At the time, the gun was seen as the primary weapon at sea, since the previously favored tactic of ramming an opponent had been rendered less feasible by the invention of self-propelled torpedoes. The Inspector General of Artillery submitted a report to the French Naval Minister, Léon Martin Fourichon, on 20 November 1876 that recommended a 120-ton gun with a bore diameter of around 440 mm (17 in), which would be able to penetrate the thickest armor then in production.[2]

As the power of guns continued to grow, thicker armor was needed to protect the ships; the full side armor of earlier ironclads could not be thickened without prohibitively increasing displacement. French designers differed from their Italian counterparts, opting to retain a complete albeit narrow waterline armor belt instead of Brin's solution, the citadel system supported by a closely compartmentalized layer. The French decision was driven by a desire to protect their ships' ability to maneuver, as the unarmored ends of the citadel ships could be easily damaged and flooded.[3]

Continued pressure from the Chamber of Deputies, particularly over the caliber of gun chosen for Amiral Duperré—340 mm (13 in) 48-ton weapons—led the designers to begin work on larger 100-ton guns for the next class, which became Amiral Baudin and Formidable.[4] On 19 January 1878, Louis Pierre Alexis Pothuau, who had succeeded Fourichon as naval minister in 1877, issued a request to shipyards in Brest and Lorient for designs for a new first-rank ironclad armed with either 75-ton or 100-ton guns. He specified the armament could be carried in single barbettes or in twin-gun turrets, both of which were to receive 550 mm (22 in) of armor protection. The belt armor was to be of equal thickness. Speed was set at 14.5 knots (26.9 km/h; 16.7 mph) from a two-shaft propulsion system. He also directed that a sailing rig was not to be fitted.[5] They were the first French capital ships to be designed without sails.[6]

During a meeting on 30 July, the Conseil des Travaux evaluated several designs and selected the one presented by the naval engineer Charles Godron. The design featured three 100-ton guns in individual barbettes, all on the centerline. Unlike their counterparts in other European navies, the French retained a secondary battery of medium caliber guns, and Godron incorporated a battery of twelve 138.6 mm (5.46 in) guns. The arrangement of the armament maximized broadside fire at the expense of end-on fire, reflecting the opinion of those who believed the torpedo had reduced the effectiveness of ramming attacks. The Conseil requested alterations to the design, which Pothuau approved on 7 September; he then forwarded the changes to Godron on the 20th. Godron completed his revised design on 6 November and submitted them to the Director of Material, Sabattier, who in turn presented in to Pothuau on 13 December. Pothuau approved it the same day and instructed the shipyards in Brest and Lorient to begin construction immediately. Three days later, Sabattier informed the Directorate of Artillery to begin work on the new 100-ton guns.[7]

The French 100-ton gun, with a 370 mm (14.6 in) bore diameter, prompted the Conseil des Travaux to call for an even larger 120-ton weapon, but the 100-ton gun was retained for the new ships. Though the ships were intended to carry the new 100-ton guns, problems aboard other vessels with new 76-ton guns prompted the naval command to abandon the as-yet untested 100-ton weapons. A modified version of the 76-ton gun with a longer barrel that had been adapted to use new propellant charges was developed; these changes gave it higher muzzle velocity, which allowed its shells to penetrate as well as the 100-ton gun had been expected to perform. Amiral Baudin and Formidable had already begun construction by the time these new guns had been developed, so they were simply substituted for the larger guns on a one-for-one basis.[8]

The class suffered from significant design faults, most significantly the arrangement of the guns; because they were placed on the centerline, they were arranged for fighting on the broadside. But their short belt, which was almost completely submerged under service conditions, did not sufficiently protect them from damage.[9] At the time of their completion, they were the most powerful vessels in the French fleet despite their flaws.[10] The Amiral Baudin design proved to be successful and led to the derivative ironclad Hoche and three-ship Marceau class.[4] The ships' period as state-of-the-art capital proved to be very brief; they were completed in 1888 and 1889, just before Britain passed the Naval Defence Act of 1889, authorizing the Royal Sovereign class of what would become known as pre-dreadnought battleships. These were significantly more powerful vessels than the ironclad vessels of the 1870s and 1880s. The French in turn responded with their Naval Law of 1890, laying down a series of experimental pre-dreadnoughts beginning with Charles Martel that year.[11][12]

General characteristics

The Amiral Baudin-class ships were 97.99 m (321 ft 6 in) long between perpendiculars, 101.4 m (332 ft 8 in) long at the waterline, and 105 m (343 ft) long overall. They had a beam of 21.34 m (70 ft) and a draft of 8.46 m (27 ft 9 in). They displaced 11,720 long tons (11,910 t). The ships had a fairly minimal superstructure, with a light conning tower with an open bridge. They were fitted with a pair of pole masts equipped with spotting tops for their main battery guns. The hull was constructed with transverse and longitudinal steel frames and had a double bottom to reduce the risk of flooding. The hull featured a pronounced tumblehome shape common to French capital ships of the period, and they incorporated a ram bow. Their crews consisted of 625 officers and enlisted men. Steering was controlled by a single rudder. The ships were difficult to maneuver and they rolled badly in service, particularly in a beam sea, making them poor gun platforms.[13][14]

The ships' propulsion machinery consisted of a pair of two-shaft, vertical compound steam engines that each drove a screw propeller. The engines were placed in separate engine rooms, divided by a watertight bulkhead. Steam for the engines was provided by twelve coal-burning fire-tube boilers, which were split into four watertight boiler rooms and were ducted into a single, large funnel just aft of the conning tower. Amiral Baudin's engines were rated to produce 6,400 indicated horsepower (4,800 kW) under normal conditions and up to 8,400 ihp (6,300 kW) at forced draft, for a top speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph), while Formidable received more powerful equipment rated for 9,700 ihp (7,200 kW) with forced draft, allowing her to reach 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph). In service, Formidable was only capable of reaching a maximum of 15.2 knots (28.2 km/h; 17.5 mph), while Amiral Baudin reached a maximum speed of 15.22 knots (28.19 km/h; 17.51 mph) on her initial trials in 1888. Coal storage amounted to 790 long tons (800 t). The ships were capable of steaming for 4,228.5 nautical miles (7,831.2 km; 4,866.1 mi) at a cruising speed of 10.69 knots (19.80 km/h; 12.30 mph).[13][15][16]

Armament and armor

The ships' main armament consisted of three 370 mm, 28-caliber M1875–79 breechloading guns mounted in individual barbette mounts, one forward, one amidships, and one aft, all on the centerline. These had been modified from the original M1875 gun to use a new propellant that burned slower than traditional black powder, producing higher muzzle velocity and improved penetration.[7] They had a very slow rate of fire, taking ten minutes to reload after every shot, common for guns of the era.[15] By 1895, the rate of fire had been improved to one shot every seven minutes, and new loading equipment installed in 1903 had increased the rate further, to three minutes and twenty seconds between shots.[17]

These guns were supported by a secondary battery of four 163 mm (6.4 in) and eight or ten 138 mm (5.4 in) guns, all carried in individual pivot mounts. The 163 mm guns were placed in sponsons in the main deck, two forward and two aft, while the 138 mm guns were in open mounts atop the main deck. These guns had a rate of fire of one shot per minute, but the blast effects of the main battery guns were so severe that the secondary gun crews had to be withdrawn from their positions when they were fired. For defense against torpedo boats, Amiral Baudin carried four 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder guns, one 47 mm 3-pounder Hotchkiss revolver cannon, and fourteen 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder Hotchkiss revolvers, all in individual mounts. Formidable had one of the 47 mm guns and twelve of the 47 mm revolvers, along with eighteen of the 1-pounder revolver cannon. Their armament was rounded out with six 381 mm (15 in) torpedo tubes in above-water mounts.[13][15]

The ships were protected with a combination of mild steel and compound armor produced by Schneider-Creusot; their belt extended for the entire length of the hull and was composed of steel. The belt was intended to extend from 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in) below the waterline to 0.90 m (2 ft 11 in) above, but overloading of the ship caused all but 0.30 m (1 ft) to be submerged, leaving most of the hull exposed to enemy fire. This seriously degraded the effectiveness of the armor and was a major weakness of the Amiral Baudin design. In the central portion, where it protected the propulsion machinery spaces and ammunition magazines, the belt was 559 mm (22 in) thick; at the top edge, it tapered slightly to 508 mm (20 in), while at the lower edge, it was reduced to 406 mm (16 in). Forward, the belt reduced to 356 to 394 mm (14 to 15.5 in) and aft it was uniformly 356 mm thick.[13][16]

The upper edge of the belt was connected to the armor deck, which was 80 mm (3 in) thick at the bow and stern and 100 mm (3.9 in) where it covered the machinery spaces. The deck was layered directly on 20 mm (0.79 in) deck plating. The barbettes for the main battery were composed of 400 mm of compound armor and the supporting tubes that protected the ammunition hoists were the same thickness, but were of steel construction. The guns themselves were protected from shell splinters by armored hoods that were 80 mm (3.1 in) thick.[13][16]

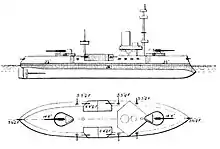

Modifications

Between 1896 and 1898, both members of the class were modernized to improve their fighting characteristics as part of a large-scale program in the late 1890s to update some fifteen ironclads that had been completed over the previous decade. The most significant alterations concerned the ships' armament. The central main battery gun was removed, along with its barbette, and a new, lightly armored battery for the 163 mm guns was erected in its place. These guns were removed from their hull sponsons and quick-firing versions were installed in the new battery. Quick-firing 138 mm guns were also installed in place of their older versions. Her light battery was revised to a pair of 65 mm (2.6 in) guns, twenty 47 mm guns, six 37 mm guns, and six 37 mm revolver cannon. The light guns were placed in fighting tops on the masts and on the superstructure. Both ships had two of their torpedo tubes removed during the refit.[13][18] The original light conning towers were replaced with armored structures that had 60 mm (2.4 in) of chrome steel on 20 mm of plating and 80 mm of armor on the fronts.[16]

Many of the French ironclads had excessively heavy superstructures that needed to be reduced, but the minimalist structures of the Amiral Baudins received only minor alterations, including enlarged bridge structures; Amiral Baudin had an enclosed bridge installed. Their light, pole fore masts were replaced with heavier military masts to support the additional light guns, while Amiral Baudin had her main mast shortened; Formidable retained her original main mast. They also received new water-tube boilers that improved performance. As a result of the alterations, the ships' crews increased slightly to 650 officers and enlisted men.[13][18]

Ships

| Name | Builder[13] | Laid down[16] | Launched[16] | Commissioned[16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiral Baudin | Brest | 1 February 1879 | 5 June 1883 | 12 January 1889 |

| Formidable | Lorient | 10 January 1879 | 16 April 1885 | 25 May 1889 |

Service history

Amiral Baudin and Formidable had relatively uneventful careers. They spent the bulk of their time in active service with the Mediterranean Fleet, where they were occupied with routine training exercises, typically in the western Mediterranean Sea and occasionally in the Atlantic in company with the Northern Squadron. In 1891, Formidable was involved in testing tethered observation balloons for use at sea. Through the early 1890s, Formidable served as the fleet flagship.[19][20][21] During exercises in 1895, Formidable accidentally led the fleet into shallow water, running aground herself and causing Amiral Baudin to become stranded as well; a third vessel struck the sea floor but did not become stuck. Formidable was pulled free easily, but Amiral Baudin had to be lightened considerably before she could be refloated. None of the ships were damaged in the accident.[22] Amiral Baudin was withdrawn from service in 1896 to be modernized and Formidable joined her the following year. Both ships were returned to active duty by 1898.[18]

As more modern pre-dreadnought battleships began to enter the fleet by the late 1890s, Amiral Baudin and Formidable were transferred from the Mediterranean Fleet—the main French naval force—to the less strategically significant Northern Squadron in 1899.[23] There, the normal routine of training exercises continued as in earlier years, including joint maneuvers with the Mediterranean Fleet. They both remained in service until 1902, when Amiral Baudin was transferred to the Reserve Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet. Formidable lingered on with the Northern Squadron that year, but was demobilized as well in 1903.[24][25][26] Formidable was briefly reactivated in 1904 to temporarily replace another vessel, but quickly returned to reserve;[27] neither vessel saw further active service and Amiral Baudin was converted into a hulk in 1909. Formidable was stricken from the naval register in 1911 and broken up, but Amiral Baudin's fate is unknown.[13]

Notes

- Ropp, pp. 92–93.

- Roberts, p. 50.

- Ropp, pp. 93–95.

- Ropp, pp. 95–96.

- Roberts, pp. 50–51.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 16.

- Roberts, p. 51.

- Ropp, pp. 95–100.

- Ropp, pp. 100–101.

- Brassey 1890, p. 179.

- Campbell, pp. 32, 291.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 22–23.

- Campbell, p. 291.

- Brassey 1890, pp. 179–180.

- Brassey 1890, p. 180.

- Roberts, p. 53.

- Roberts, p. 52.

- Weyl 1898, p. 29.

- Brassey 1891, pp. 33–40.

- Thursfield 1894, pp. 72–77.

- Masson, pp. 311–314.

- Weyl 1896, pp. 19–20.

- Leyland 1899, pp. 33, 40.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 217–218.

- Brassey 1902, pp. 47–48.

- Brassey 1903, pp. 57–58.

- Brassey 1904, pp. 88–89.

References

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1890). "Ships Lately Completed and in Progress: The Formidable". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 179–180. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1891). "Foreign Maneouvres: I—France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 33–40. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1902). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 47–55. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1903). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 57–68. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1904). "Chapter IV: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 86–107. OCLC 496786828.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "France". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 283–333. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Leyland, John (1899). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 32–69. OCLC 496786828.

- Masson, G., ed. (1890). "Les Áerostats Captifs" [The Captive Aerostats]. La Nature (in French). Paris: Libraire de L'Académie de Médecine. OCLC 1108911748.

- Roberts, Stephen (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914. Barnsley: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-5267-4533-0.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1894). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Foreign Maneouvres: I—France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 71–102. OCLC 496786828.

- Weyl, E. (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 17–60. OCLC 496786828.

- Weyl, E. (1898). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 19–55. OCLC 496786828.