Annunciation in Christian art

The Annunciation has been one of the most frequent subjects of Christian art.[1][2] Depictions of the Annunciation go back to early Christianity, with the Priscilla catacomb in Rome including the oldest known fresco of the Annunciation, dating to the 4th century.[3]

Scenes depicting the Annunciation represent the perpetual virginity of Mary via the announcement by the angel Gabriel that Mary would conceive a child to be born the son of God.

The scene is an invariable one in cycles of the Life of the Virgin, and often included as the initial scene in those of the Life of Christ. Frescos depicting this scene have appeared in Roman Catholic Marian churches for centuries, and it has been a topic addressed by many artists in multiple media, ranging from stained glass to mosaic, to relief, to sculpture to oil painting.[4]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Particularly popular during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, it appears in the work of almost all of the great masters. The figures of the Virgin Mary and the archangel Gabriel, were favorite subjects of Roman Catholic Marian art. Works on the subject have been created by Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, Duccio di Buoninsegna, Jan van Eyck, Murillo, and thousands of other artists. The mosaics of Pietro Cavallini in Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome (1291), the frescos of Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (1303), Domenico Ghirlandaio's fresco at the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence (1486), and Donatello's gilded sculpture at the church of Santa Croce, Florence (1435) are famous examples.

The composition of depictions is very consistent, with Gabriel, normally standing on the left, facing the Virgin, who is generally seated or kneeling, at least in later depictions. Typically, Gabriel is shown in near-profile, while the Virgin faces more to the front. She is usually shown indoors, or in a porch of some kind, in which case Gabriel may be outside the building entirely, in the Renaissance often in a garden, which refers to the hortus conclusus, sometimes an explicit setting for Annunciations. The building is sometimes clearly the Virgin's home, but is also often intended to represent the Jerusalem Temple, as some legendary accounts placed the scene there. The Virgin may be shown reading, as medieval legend dating back to at least the time of the Church Fathers in Ambrose represented her as a considerable scholar,[5] or engaged in a domestic task, often reflecting another legend that she was one of a number of virgins asked to weave a new Veil of the Temple.[6] Late medieval commentators distinguished several phases of the Virgin's reaction to the appearance of Gabriel and the news, from initial alarm at the sudden vision, followed by reluctance to fulfill the role, to a final acceptance. These are reflected in art by the Virgin's posture and expression.

In Late Medieval and Early Renaissance, the grace of the Virgin in God's sight may be indicated by rays falling on her, typically through a window, as light passing through a window was a frequent metaphor in devotional writing for her virginal conception of Jesus. Sometimes a small figure of God the Father or the Holy Spirit as a dove is seen in the air, as the source of the rays. Less common examples feature other biblical figures in the scene. Gabriel, especially in northern Europe, is often shown wearing the vestments of a deacon on a grand feast day, with a cope fastened at the centre with a large morse (brooch). Especially in Early Netherlandish painting, images may contain very complex programmes of visual references, with a number of domestic objects having significance in reinforcing the theology of the event. Well-known examples are the Mérode Altarpiece of Robert Campin, and the Annunciation by Jan van Eyck in Washington.

Byzantine Rite

Byzantine Rite icons display, as is usual, even more consistent compositions than medieval Western images. The Virgin is nearly always on the right, normally either standing or seated on a throne with a building behind her; there are also often buildings visible behind Gabriel. These styles were generally copied in the West until a surprisingly late date, around the 13th century; more varied Western depictions were slower to develop than with other standard religious subjects.

Because of the natural composition of the scene as two figures facing each other, the subject was often employed in the decoration of a diptych or tympaneum (decorated arch above a doorway). In churches of the Byzantine Rite, the Annunciation is typically depicted on the Holy Doors (decorative doorway leading from the nave into the sanctuary), and in the West the two figures are also found on different surfaces, in the outer panels of polyptychs that have an open and closed view, the doors of tabernacles, or simply on facing pages in illuminated manuscripts or different compartments of large altarpieces.

Gallery of artworks

Annunciation of Ustyug, 12th century

Annunciation of Ustyug, 12th century 13th-century Byzantine icon, Saint Catherine's Monastery

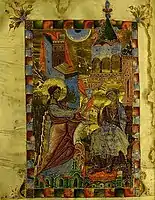

13th-century Byzantine icon, Saint Catherine's Monastery Armenian illumination from the Gospel (1287, Matenadaran).

Armenian illumination from the Gospel (1287, Matenadaran). Byzantine icon, early 14th century

Byzantine icon, early 14th century German miniature of c. 1275, still closely following Byzantine models

German miniature of c. 1275, still closely following Byzantine models.jpg.webp) Annunciation by Pedro Berruguete, 15th century

Annunciation by Pedro Berruguete, 15th century The Virgin Annunciate by Carlo Crivelli, 15th century; rays enter through the window

The Virgin Annunciate by Carlo Crivelli, 15th century; rays enter through the window Annunciation by Jan van Eyck, 1434; unsurpassed painting of texture.

Annunciation by Jan van Eyck, 1434; unsurpassed painting of texture. Rogier van der Weyden, 1435

Rogier van der Weyden, 1435 Annunciation by Filippo Lippi, 1443

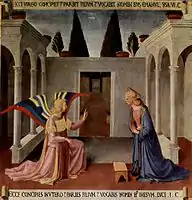

Annunciation by Filippo Lippi, 1443 Annunciation by Fra Angelico, 1450

Annunciation by Fra Angelico, 1450

Benvenuto di Giovanni, 1470

Benvenuto di Giovanni, 1470 Annunciation by Leonardo da Vinci, 1472–75

Annunciation by Leonardo da Vinci, 1472–75 Annunciation, Our Lady of Sorrows Triptych in Holy Cross Chapel in Wawel Cathedral, Kraków, Poland, 1475–1485

Annunciation, Our Lady of Sorrows Triptych in Holy Cross Chapel in Wawel Cathedral, Kraków, Poland, 1475–1485 Annunciation by Piermatteo Lauro de' Manfredi da Amelia at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, c. 1485

Annunciation by Piermatteo Lauro de' Manfredi da Amelia at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, c. 1485 Annunciation of Fano by Pietro Perugino, 1489

Annunciation of Fano by Pietro Perugino, 1489 Annunciation by Jean Hey, 1490

Annunciation by Jean Hey, 1490 Cestello Annunciation by Botticelli, 1490

Cestello Annunciation by Botticelli, 1490 Annunciation by Federico Barocci, 16th century

Annunciation by Federico Barocci, 16th century Panel from the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald, 1512–1516

Panel from the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald, 1512–1516 German Altarpiece, 1518

German Altarpiece, 1518 Recanati Annunciation by Lorenzo Lotto, c. 1534

Recanati Annunciation by Lorenzo Lotto, c. 1534 Annunciation by Eustache Le Sueur, 17th century

Annunciation by Eustache Le Sueur, 17th century.jpg.webp) Annunciation by Hans von Aachen, 1610

Annunciation by Hans von Aachen, 1610.jpg.webp) Annunciation, 1610, Mexico

Annunciation, 1610, Mexico Annunciation by Rubens, 1628

Annunciation by Rubens, 1628 Philippe de Champaigne, 1644

Philippe de Champaigne, 1644 Annunciation by Murillo, 1655

Annunciation by Murillo, 1655 Mikhail Nesterov, 19th century

Mikhail Nesterov, 19th century

Annunciation by John William Waterhouse, 1914

Annunciation by John William Waterhouse, 1914.jpg.webp) Annunciation window at Church of the Good Shepherd (Rosemont, Pennsylvania), c. 1910

Annunciation window at Church of the Good Shepherd (Rosemont, Pennsylvania), c. 1910

See also

References

- The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture by Peter Murray and Linda Murray 1996 ISBN 0-19-866165-7 page 23

- Images of the Mother of God: by Maria Vassilaki 2005 ISBN 0-7546-3603-8 pages 158–159

- The Annunciation To Mary by Eugene LaVerdiere 2007 ISBN 1-56854-557-6 page 29

- Annunciation Art, Phaidon Press, 2004, ISBN 0-7148-4447-0

- Miles, Laura Saetveit (July 2014). "The Origins and Development of the Virgin Mary's Book at the Annunciation". Speculum. 89 (3): 639. JSTOR 43577031.

- Stracke, Richard. "The Annunciation", Christian Iconography, Augusta University