Antonio da Correggio

Antonio Allegri da Correggio (August 1489 – 5 March 1534), usually known as just Correggio (/kəˈrɛdʒioʊ/, also UK: /kɒˈ-/, US: /-dʒoʊ/,[1][2][3] Italian: [korˈreddʒo]), was the foremost painter of the Parma school of the High Italian Renaissance, who was responsible for some of the most vigorous and sensuous works of the sixteenth century. In his use of dynamic composition, illusionistic perspective and dramatic foreshortening, Correggio prefigured the Baroque art of the seventeenth century and the Rococo art of the eighteenth century. He is considered a master of chiaroscuro.

Antonio da Correggio | |

|---|---|

Antonio Allegri da Correggio | |

| Born | Antonio Allegri August 1489 |

| Died | 5 March 1534 (aged 44) Correggio, Duchy of Modena and Reggio |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Fresco, painting |

| Notable work | Jupiter and Io Assumption of the Virgin |

| Movement | High Renaissance Mannerism |

Early life

Antonio Allegri was born in Correggio, a small town near Reggio Emilia. His date of birth is uncertain (around 1489). His father was a merchant.[4] Otherwise little is known about Correggio's early life or training. It is, however, often assumed that he had his first artistic education from his father's brother, the painter Lorenzo Allegri.[5]

In 1503–1505, he was apprenticed to Francesco Bianchi Ferrara in Modena, where he probably became familiar with the classicism of artists like Lorenzo Costa and Francesco Francia, evidence of which can be found in his first works. After a trip to Mantua in 1506, he returned to Correggio, where he stayed until 1510. To this period is assigned the Adoration of the Child with St. Elizabeth and John, which shows clear influences from Costa and Mantegna. In 1514, he probably finished three tondos for the entrance of the church of Sant'Andrea in Mantua, and then returned to Correggio, where, as an independent and increasingly renowned artist, he signed a contract for the Madonna altarpiece in the local monastery of St. Francis (now in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie).

One of his sons, Pomponio Allegri, became an undistinguished painter. Both father and son occasionally referred to themselves using the Latinized form of the family name, Laeti.[6]

Works in Parma

By 1516, Correggio was in Parma, where he spent most of the remainder of his career. Here, he befriended Michelangelo Anselmi, a prominent Mannerist painter. In 1519 he married Girolama Francesca di Braghetis, also of Correggio, who died in 1529.[7] From this period are the Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John, Christ Leaving His Mother and the lost Madonna of Albinea.

Correggio's first major commission (February–September 1519) was the ceiling decoration of a private chamber of the mother-superior (abbess Giovanna Piacenza) of the convent of St. Paul in Parma, now known as Camera di San Paolo. Here he painted an arbor pierced by oculi opening to glimpses of playful cherubs. Below the oculi are lunettes with images of statues in feigned monochromic marble. The fireplace is frescoed with an image of Diana. The iconography of the scheme is complex, combining images of classical marbles with whimsical colorful bambini.

He then painted the illusionistic Vision of St. John on Patmos (1520–21) for the dome of the church of San Giovanni Evangelista. Three years later he decorated the dome of the Cathedral of Parma with a startling Assumption of the Virgin, crowded with layers of receding figures in Melozzo's perspective (sotto in su, from down to up).[7] These two works represented a highly novel illusionistic sotto in su treatment of dome decoration that would exert a profound influence upon future fresco artists, from Carlo Cignani in his fresco Assumption of the Virgin, in the cathedral church of Forlì, to Gaudenzio Ferrari in his frescoes for the cupola of Santa Maria dei Miracoli in Saronno, to Pordenone in his now-lost fresco from Treviso, and to the baroque elaborations of Lanfranco and Baciccio in Roman churches. The massing of spectators in a vortex, creating both narrative and decoration, the illusionistic obliteration of the architectural roof-plane, and the thrusting perspective toward divine infinity, were devices without precedent, and which depended on the extrapolation of the mechanics of perspective. The recession and movement implied by the figures presage the dynamism that would characterize Baroque painting.

Other masterpieces include The Lamentation and The Martyrdom of Four Saints, both at the Galleria Nazionale of Parma. The Lamentation is haunted by a lambency rarely seen in Italian painting prior to this time.[8] The Martyrdom is also remarkable for resembling later Baroque compositions such as Bernini's Truth and Ercole Ferrata's Death of Saint Agnes, showing a gleeful saint entering martyrdom.[8]

Mythological series

Aside from his religious output, Correggio conceived a now-famous set of paintings depicting the Loves of Jupiter as described in Ovid's Metamorphoses. The voluptuous series was commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga of Mantua, probably to decorate his private Ovid Room in the Palazzo Te. However, they were given to the visiting Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and thus left Italy within years of their completion.

Leda and the Swan – acquired by Frederick the Great in 1753; now in Staatliche Museen of Berlin – is a tumult of incidents: in the centre Leda straddles a swan, and on the right, a shy but satisfied maiden. Danaë, now in Rome's Borghese Gallery, depicts the maiden as she is impregnated by a curtain of gilded divine rain. Her lower torso semi-obscured by sheets, Danae appears more demure and gleeful than Titian's 1545 version of the same topic, where the rain is more accurately numismatic. The picture once called Antiope and the Satyr is now correctly identified as Venus and Cupid with a Satyr.

Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle depicts the young man aloft in literal amorous flight. Some have interpreted the conjunction of man and eagle as a metaphor for the evangelist John; however, given the erotic context of this and other paintings, this seems unlikely. This painting and its partner, the masterpiece of Jupiter and Io, are in Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna. Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle, one of the four mythological paintings commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga, is a proto-Baroque work due to its depiction of movement, drama, and diagonal compositional arrangement.

Death

Returning to his home town in later years, Correggio died there suddenly on 5 March 1534. The following day he was buried in San Francesco in Correggio near his youthful masterpiece, the 'Madonna di San Francesco', housed today in Dresden. The precise location of his tomb is now unknown.

Evaluation

Correggio was remembered by his contemporaries as a shadowy, melancholic, and introverted character. An enigmatic and eclectic artist, he appears to have emerged from no major apprenticeship. In addition to the influence of Costa, there are echoes of Mantegna's style in his work, and a response to Leonardo da Vinci, as well. Correggio had little immediate influence in terms of apprenticed successors, but his works are now considered to have been revolutionary and influential on subsequent artists. A half-century after his death Correggio's work was well known to Vasari, who felt that he had not had enough "Roman" exposure to make him a better painter. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, his works were often noted in the diaries of foreign visitors to Italy, which led to a reevaluation of his art during the period of Romanticism. The flight of the Madonna in the vault of the cupola of the Cathedral of Parma inspired many scenographical decorations in lay and religious palaces during those centuries.

Correggio's illusionistic experiments, in which imaginary spaces replace the natural reality, seem to prefigure many elements of Mannerist, Baroque, and Rococo stylistic approaches. He appears to have fostered artistic grandchildren, for example, Giovannino di Pomponio Allegri (1521–1593).[9] Correggio had no direct disciples outside of Parma, where he was influential on the work of Giovanni Maria Francesco Rondani, Parmigianino, Bernardo Gatti, Francesco Madonnina, and Giorgio Gandini del Grano.

Selected works

_02.jpg.webp)

- Judith and the Servant (c. 1510)—Oil on canvas,Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg

- Holy Family with Saints Elizabeth and John the Baptist (c. 1510)—Oil on panel-Pavia Civic Museums, Pavia[10]

- The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (1510–1515)—National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Madonna (1512–14)—Oil on canvas, Castello Sforzesco, Milan

- Madonna and Child with St Francis (1514)—Oil on wood, 299 × 245 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- Madonna and Child (unknown, early 1500s)—Oil on canvas, National Gallery for Foreign Art, Sofia

- Madonna of Albinea (1514, lost)

- Madonna and Child with the infant Saint John the Baptist (1514–15)—Oil on wood panel, 45 × 35.5 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

- Madonna and Child with the Infant John the Baptist (c. 1515)—Oil on panel, 64.2 × 50.2 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

- The Holy Family with Saint Jerome (1515)–East Closet of Hampton Court Palace as part of the Royal Collection

- Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John (1516)—Oil on canvas, 48 × 37 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid[11]

- Adoration of the Magi (c. 1515–1518)–Oil on canvas, 84 × 108 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

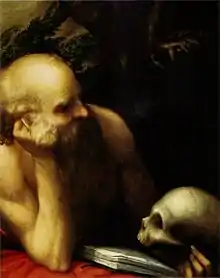

- Saint Jerome (c. 1515–1518)–Oil on Wood 64 x 51 cm, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid[12]

- Madonna and Child with the Infant John the Baptist (1518)–Oil on panel, 48 x 37 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Portrait of a Gentlewoman (1517–1519)—Oil on canvas, 103 × 87.5 cm, Hermitage, St. Petersburg

- Frescoes for Camera di San Paolo (1519)—Monastery of San Paolo, Parma

- The Rest on the Flight to Egypt with Saint Francis (c. 1520)—Oil on canvas, 123.5 × 106.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- Portrait of a man (c. 1520)–Oil on canvas, 55 x 40 cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen Bornemisza, Madrid[13].

- Death of St. John (1520–1524)—Fresco, San Giovanni Evangelista, Parma

- Madonna della Scala (c. 1523)—Fresco, 196 × 141.8 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

St. Jerome, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, c. 1515–1518

St. Jerome, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, c. 1515–1518 - Martyrdom of Four Saints (c. 1524)—Oil on canvas, 160 × 185 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Virgin and Child with an Angel (Madonna del Latte) (c. 1524)—Oil on wood, 68 × 56 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- Deposition from the Cross (1525)—Oil on canvas, 158.5 × 184.3 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Noli me Tangere (c. 1525)—Oil on canvas, 130 × 103 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid[14]

- Ecce Homo (1525–1530)—Oil on canvas, National Gallery, London

- Madonna della Scodella (1525–1530)—Oil on canvas, 216 × 137 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Adoration of the Child (c. 1526)—Oil on canvas, 81 × 67 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (mid-1520s)—Wood, 105 × 102 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Assumption of the Virgin (1526–1530)—Fresco, 1093 × 1195 cm, Cathedral of Parma

- Madonna of St. Jerome (1527–28)—Oil on canvas, 205.7 × 141 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Venus with Mercury and Cupid ('The School of Love') (c. 1528)—Oil on canvas, 155 × 91 cm, National Gallery, London

- Venus and Cupid with a Satyr (c. 1528)—Oil on canvas, 188 × 125 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Nativity (Adoration of the Shepherds, or Holy Night) (1528–1530)—Oil on canvas, 256.5 × 188 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- Madonna and Child with Saint George (1530–1532)—Oil on canvas, 285 × 190 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- Danaë (c. 1531)—Tempera on panel, 161 × 193 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle (1531–32)—Oil on canvas, 163.5 × 70.5 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Jupiter and Io (1531–32)—Oil on canvas, 164 × 71 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Leda with the Swan (1531–32)—Oil on canvas, 152 × 191 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

- Allegory of Virtue (c. 1531)—Oil on canvas, 149 × 88 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Allegory of Vice (c. 1531)—Oil on canvas, 149 × 88 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Selected works

The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine, c. 1526–27

The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine, c. 1526–27_(Italian)_-_Head_of_Christ_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Head of Christ (1525–1530)

Head of Christ (1525–1530)

Venus and Cupid (1525)

Venus and Cupid (1525) Assumption of the Virgin, Duomo, Parma, 1522–30

Assumption of the Virgin, Duomo, Parma, 1522–30

Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle (1531–32)

Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle (1531–32) Portrait of a Man (c. 1520), Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

Portrait of a Man (c. 1520), Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

References

- "Correggio". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- "Correggio" (US) and "Correggio". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020.

- "Correggio". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- "High Quality Reproductions Of Correggio (Antonio Allegri) paintings". www.antoniodacorreggio.org. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Ricci, Conrado (1896). Antonio Allegri da Correggio: His Life, his Friends, and his Time. London: William Heinemann. p. 43.

- Henry Fuseli, Aphorisms. A history of art in the schools of Italy, in The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli, Esq. M.A.R.A., Vol. III, p. 91

- Rossetti, William Michael (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Antonio Corregio Artwork Authentication & Art Appraisal". www.artexpertswebsite.com. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Guida al Museo il Correggio.

- "Sacra Famiglia con santa Elisabetta". La Pinacoteca Malaspina. Musei Civici di Pavia. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- "The Virgin and Child with Saint John - The Collection - Museo Nacional del Prado". www.museodelprado.es. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Fernando, Real Academia de BBAA de San. "Correggio, Antonio Allegri - San Jerónimo". Academia Colecciones (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Portrait of a Man". Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Noli me tangere - Colección - Museo Nacional del Prado". www.museodelprado.es. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

External links

![]() Media related to Antonio da Correggio at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Antonio da Correggio at Wikimedia Commons

- 66 artworks by or after Antonio da Correggio at the Art UK site

- Works by Correggio at Project Gutenberg

- http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/correggio/

- Freedberg, Sydney J. (1993). Pelican History of Art (ed.). Painting in Italy, 1500–600. Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 267–290, 412–416.

- Catholic Encyclopedia article It does not cite the mythological theme pictures.

- Correggio, by Estelle M. Hurll, 1901, from Project Gutenberg

- Works by Correggio at www.antoniodacorreggio.org

- Correggio exposition in Rome, Villa Borghese, 2008

- Video—Il Duomo di Parma, Assumption of the Virgin

- Dr. Julius Meyer, Antonio da Correggio

- More complete list of works by Correggio (with images)