Aortic valve

The aortic valve is a valve in the heart of humans and most other animals, located between the left ventricle and the aorta. It is one of the four valves of the heart and one of the two semilunar valves, the other being the pulmonary valve. The aortic valve normally has three cusps or leaflets, although in 1–2% of the population it is found to congenitally have two leaflets.[1] The aortic valve is the last structure in the heart the blood travels through before stopping the flow through the systemic circulation.

| Aortic valve | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Frontal view of the Aortic valve | |

Aortic valve | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | valva aortae |

| MeSH | D001021 |

| TA98 | A12.1.04.012 |

| TA2 | 3993 |

| FMA | 7236 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

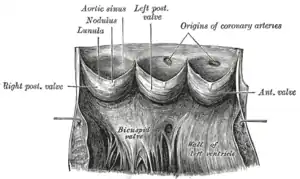

The aortic valve normally has three cusps however there is some discrepancy in their naming.[2] They may be called the left coronary, right coronary and non-coronary cusp.[2] Some sources also advocate they be named as a left, right and posterior cusp.[3][4] Anatomists have traditionally named them the left posterior (origin of left coronary), anterior (origin of the right coronary) and right posterior.[2]

The three cusps, when the valve is closed, contain a sinus called an aortic sinus or sinus of Valsalva. In two of these cusps, the origin of the coronary arteries are found. The width of the sinuses in cross-section is wider than the left ventricular outflow tract as well as wider than the ascending aorta. The junction of the sinuses with the aorta is called the sinotubular junction. The aortic valve is located posterior to the pulmonary valve and the commissure where the anterior two cusps join together points toward the pulmonary valve. It is these two sinuses that contain the origin of the coronary arteries. In the congenital disease known as transposition of the great arteries, these two valves are reversed (the anterior valve is the aortic valve) and the origin of the coronaries still follows this "rule" that the origins are in the sinuses facing the pulmonary valve.

.jpg.webp)

The term "semilunar" refers to an approximate half-moon shape of the valve leaflets.[5]

Function

When the left ventricle contracts (systole), pressure rises in the left ventricle. When the pressure in the left ventricle rises above the pressure in the aorta, the aortic valve opens, allowing blood to exit the left ventricle into the aorta. When ventricular systole ends, pressure in the left ventricle rapidly drops. When the pressure in the left ventricle decreases, the momentum of the vortex at the outlet of the valve forces the aortic valve to close. The closure of the aortic valve contributes the A2 component of the second heart sound (S2).

Insufficiency

Closure of the aortic valve permits maintaining high pressures in the systemic circulation while reducing pressure in the left ventricle to permit blood flow from the lungs to fill the left ventricle. Abrupt loss of function of the aortic valve results in acute aortic insufficiency and loss in the normal diastolic blood pressure resulting in a wide pulse pressure and bounding pulses. The endocardium perfuses during diastole and so acute aortic insufficiency (also known as aortic regurgitation) can reduce perfusion of the heart. Consequently, heart failure and pulmonary edema can develop.

Slowly worsening aortic insufficiency results in a chronic insufficiency which permits the heart to compensate (unlike acute insufficiency). This compensation is through hypertrophy of the left ventricle and return to normal filling pressures.

Stenosis

Inadequate opening of the aortic valve, often through calcification, results in higher flow velocities through the valve and larger pressure gradients. Diagnosis of aortic stenosis is contingent upon quantification of this gradient. This condition also results in hypertrophy of the left ventricle.

Clinical significance

A normally functioning valve permits normal physiology and dysfunction of the valve results in left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure. Dysfunctional aortic valves often present as heart failure by non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, low energy, and shortness of breath with exertion. Common causes of aortic regurgitation include vasodilation of the aorta, previous rheumatic fever, infection such as infective endocarditis, degeneration of the aortic valve, and Marfan's syndrome. Aortic stenosis can also be caused by rheumatic fever and degenerative calcification.[6] The most common congenital heart defect is the bicuspid aortic valve (fusion of two cusps together) commonly found in Turner syndrome. Once diagnosed, the two options are to repair or replace the valve.

Aortic valve repair

Aortic valve repair or aortic valve reconstruction describes the reconstruction of both form and function of the native and dysfunctioning aortic valve. Most frequently it is applied for the treatment of aortic regurgitation. It can also become necessary for the treatment of aortic aneurysm, or less frequently for congenital aortic stenosis.[7]

Aortic valve replacement

Replacement of the aortic valve is done by replacing the native valve with a prosthetic valve. Traditionally, this has been a surgical procedure (surgical AVR or SAVR) but a non-surgical option called transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) or TAVI transcatheter aortic valve implantation delivers a prosthetic valve through a catheter.[8] The choice between SAVR and TAVR often relies on the open-heart surgical risk and indications for other open heart surgeries (etc., coronary bypass, other valve dysfunction). The Bentall procedure is a type of surgical procedure when the aortic valve, aortic root, and ascending aorta are replaced in a single operation.

There are two basic types of artificial heart valve: mechanical and tissue.

- Mechanical valves are made of metal and have evolved over time ("ball and cage", "bileaflet"). Mechanical valves require lifelong anticoagulation to avoid forming blood clots on the valves that can lead to embolism often resulting in stroke. These tend to be favored in younger individuals as they typically last longer than tissue valves. The shape of these valves do not mimic normal heart valves.

- Tissue heart valves are usually made from animal tissues, either animal heart valve tissue or animal pericardial tissue, and commonly porcine. The tissue is pretreated by removing antigens to prevent rejection and to prevent calcification. These valves tend to model after normal valves by having leaflets that form cusps and sinuses.

There are alternatives to animal tissue valves. In some cases, a human aortic valve can be implanted. These are called homografts. Homograft valves are donated by patients and recovered after the patient expires. The durability of homograft valves is probably the same as for porcine tissue valves. Another procedure for aortic valve replacement is the Ross procedure (after Donald Ross) or pulmonary autograft. The Ross procedure involves going to surgery to have the aortic valve removed and replacing it with the patient's own pulmonary valve. A pulmonary homograft (a pulmonary valve taken from a cadaver) or a valvular prothesis is then used to replace the patient's own pulmonary valve.

The first minimally invasive aortic valve surgery took place at the Cleveland Clinic in 1996.

Endocarditis

Endocarditis is infection of the heart and this often results in vegetations growing on valves. While it is possible for it to affect the aortic valve, it is not the most likely spot.

Evaluation

Evaluation of the aortic valve can be done with several modalities. Auscultation with a stethoscope is quick and easy. It contributes the A2 component to the second heart sound and changes with inspiration ("splitting") Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is used as the first test because it is non-invasive. Using TTE, the degree of stenosis and insufficiency can be quantified to grade the valve dysfunction. Transesophageal echocardiography is less often used for aortic stenosis & insufficiency because the angle between the probe and the aortic valve is not optimal (the best window is a transgastric view). MRI and CT can be used to evaluate the valve, but much less commonly than TTE.

Quantification of the maximum velocity through the valve, the area of the opening of the valve, calcification, morphology (tricuspid, bicuspid, unicuspid), and size of the valve (annulus, sinuses, sinotubular junction) are common parameters when evaluating the aortic valve.

Invasive measurement of the aortic valve can be done during a cardiac catheterization in which the pressure in the left ventricle and aorta can be measured simultaneously.

Additional images

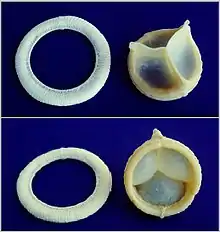

A replaceable model of Cardiac Biological Valve Prosthesis.

A replaceable model of Cardiac Biological Valve Prosthesis.

Aortic valve

Aortic valve

References

- Bayne, Edward J (8 January 2016). "Bicuspid Aortic Valve: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". Medscape. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Ho, SY (January 2009). "Structure and anatomy of the aortic root". European Journal of Echocardiography. 10 (1): i3-10. doi:10.1093/ejechocard/jen243. PMID 19131496.

- Anatomy photo:20:29-0104 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Heart: The Aortic Valve and Aortic Sinuses"

- Last's anatomy, regional and applied (9th. ed.). Churchill Livingstone. 1994. p. 268. ISBN 044304662X.

- "Anatomy of the Heart: Valves". 2019. Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- Aortic Valve, Bicuspid at eMedicine

- Hans-Joachim Schäfers: Current treatment of aortic regurgitation. UNI-MED Science, Bremen, London, Boston 2013, ISBN 978-3-8374-1406-6.

- "What is TAVR?". American Heart Association. 2014. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

External links

- Anatomy figure: 20:07-02 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center