Arab Indonesians

Arab Indonesians (Arabic: عربٌ إندونيسيون) or, colloquially known as Jama'ah,[3] and until the 20th century was also called Codjas or Kodjas,[4][5] are Indonesian citizens of mixed Arab – mainly Hadhrami – and Indonesian descent. The ethnic group generally also includes those of Arab descent from other Middle Eastern Arabic speaking nations. Restricted under Dutch East Indies law until 1919, the community elites later gained economic power through real estate investment and trading. Currently found mainly in Java, especially West Java and South Sumatra, they are almost all Muslims.[6]

Orang Arab Indonesia عرب إندونيسيا | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Aceh, North Sumatra, West Sumatra, South Sumatra, Banten, Jakarta, West Java, Central Java, East Java, South Kalimantan, West Kalimantan, South Sulawesi, Maluku Islands | |

| Languages | |

| Indonesian, Arabic, Various Indonesian regional languages | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hadhramis, Arab Malaysians, Arab Singaporeans, Arab diaspora |

The official number of Arab and part-Arab descent in Indonesia was recorded since 19th century. The census of 1870 recorded a total of 12,412 Arab Indonesians (7,495 living in Java and Madura and the rest in other islands). By 1900, the total number of Arabs citizens increased to 27,399, then 44,902 by 1920, and 71,335 by 1930.[7]

History

Indonesia has had contact with the Arab world prior to the emergence of Islam in Indonesia as well as since pre-Islamic times. The earliest Arabs to arrive in Indonesia were traders who came from Southern Arabia and other Arab states of the Persian Gulf.[8] Arab traders helped bring the spices of Indonesia, such as nutmeg, to Europe as early as the 8th century.[9] However, Arab settlements mostly began only in the early Islamic era.[10][11] These traders helped to connect the spice and silk markets of South East Asia and far east Asia with the Arabian kingdoms, Persian Empire and the Roman Empire. Some later founded dynasties, including the Sultanate of Pontianak, while others intermingled with existing kingdoms. These early communities adopted much of the local culture, and some disappeared entirely while others formed ethnically distinct communities.[12]

More Arabs visited Malay Archipelago when Islam began to spread. Islam was brought to the region directly from Arabia (as well as Persia and Gujarat), first to Aceh.[13] One of travelers who had visited Indonesia was the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta who visited Samudra Pasai in 1345-1346 CE. According to Muslim Chinese writer Ma Huan who visited north coast of Java in 1413–15, he noted three kinds of people there: Chinese, local people and Muslims from foreign kingdoms in the West (Mideast) who have migrated to the country as merchants.[10]

Modern Arab Indonesians are generally descended of Hadhrami immigrants,[14] although there are also communities coming from Arabs of Egypt, Sudan, Oman, and Arab States of the Persian Gulf area as well as non-Arab Muslims from Turkey or Iran. The Arabs and some of non-Arabs arrived during the Ottoman expedition to Aceh, which consisted of Egyptians, Swahili, Somalis from Mogadishu, and Indians from various cities, and states. They were generally from upper strata and classified as "foreign orientals" (Vreemde Oosterlingen) along with Chinese Indonesians by the Dutch colonists, which led to them being unable to attend certain schools and restricted from travelling, and having to settle in special Arab districts, or Kampung Arab. These laws were repealed in 1919.[15] As liaison and to lead the community, the Dutch government appointed some Kapitan Arabs in the districts.

The community elites began to build economic power through trade and real estate acquisition, buying large amounts of real estate in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta), Singapore and other parts of the archipelago. Through charity work and "conspicuous consumption", they built and protected their social capital; eventually, some Arab Indonesians joined the Volksraad, the people's council of the Dutch East Indies.[16]

During the Indonesian National Awakening, an Indonesian nationalist movement, Persatuan Arab Indonesia, founded by Abdurrahman Baswedan in 1934, promoted the idea of gradual cultural assimilation of Arab Indonesians into wider Indonesian society, which Baswedan referred to as "cultural reorientation".[17]

Identity

First generation immigrants are referred to as wulayātī or totok. They are a small minority of the Arab Indonesian population. The majority, muwallad, were born in Indonesia and may be of mixed heritage.[18]

Because of the lack of information, a few Indonesian scholars have mistaken the Arabs of Indonesia as Wahhabism agents, as Azyumardi Azra depicts Indonesians of Arab descent as wishing to purge Indonesian Islam of its indigenous religious elements. Indonesian critics of Arab influence in Indonesia point to the founding of the radical group Jemaah Islamiah (JI) and leadership of Laskar Jihad (LJ) and Front Pembela Islam by Indonesian Arabs.[19][20]

Distribution

The majority of Arab Indonesians live in Java and Madura, usually in cities or relatively big towns such as Jakarta, Pekalongan, Solo, Gresik or Surabaya. A sizeable population is also found in Sumatra (primarily in Palembang, and some in West Sumatra, North Sumatra, Riau, and Aceh),[21] Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Maluku. The earliest census figures that indicate the number of Hadhramis living in Dutch East Indies date from 1859, when it was found that there were 4,992 Arab Indonesians living in Java and Madura.[22] The census of 1870 recorded a total of 12,412 Arab Indonesians (7,495 living in Java and Madura and the rest in other islands). In 1900, total number of Arab population 27,399, 44,902 in 1920, and 71,335 in 1930.[22] Census data shows 87,066 people in 2000, and 87,227 people in 2005, who identified themselves as being of Arab ethnicity, representing 0.040% of the population.[23] The number of Indonesians with partial Arab ancestry, who do not identify as Arab, is unknown. It has been speculated to be several million.[24]

Religion

.png.webp)

Arab Indonesians are almost all Muslim; according to the 2000 census. Historically, most have lived in so called Kauman villages, in the areas around mosques, but this has changed in recent years.[25] The majority are Sunni, following the Shafi'i school of Islamic law with Ba 'Alawi sada families usually follow Ba 'Alawiyya tariqa.[26]

The Islam practiced by Arab Indonesians tends to be more orthodox than the local, indigenous-influenced forms like abangan who do not follow some of the more restrictive Islamic practices. Children are generally sent to madrasahs,[27] but many later advanced their education to secular schools.

Traditions

Music

Gambus is a popular musical genre among Arab-Indonesians, usually during weddings or other special events. The music is played by a music ensemble consisting of Lute, violins, Marawis, Dumbuk, Bongo drum, Tambourine, Suling (Indonesian version of Ney),[28] and sometimes accompanied with Accordion, Electronic keyboard, Electric guitars, even drum kit. The Lute (Gambus) player (commonly called Muthrib) usually sings while playing the Lute. The music is very similar to Yemeni music with lyrics mainly in Arabic, similar to Khaliji music, where the rhythm is categorized as either Dahife, Sarh or Zafin.[29] In the events, sometimes male-only dancers go to the middle in a group of two or three persons and each group takes turn in the middle of the song being played.

Cuisine

Just like the Chinese and the Indians, the Arabs also brought their own culinary traditions as well as cuisine to Indonesia.

The influence of Hadhrami immigrants in the Indonesian cuisine can be seen in the presence of Yemeni cuisine in Indonesia, such as Nasi kebuli, Mandi rice, Ka'ak cookie,[30] Murtabak, or lamb Maraq (lamb soup or stew).[31][32]

Ancestry

As common among Middle-Eastern societies, genealogies are mainly patrilineal.[33] Patrilinearity is even stronger in Sayyid families, where an offspring of non-Hadhrami man and Hadhrami woman is not considered a Sayyid.[28] Many of the Hadhrami migrants came from places in Hadhramaut, such as Seiyun, Tarim, Mukalla, Shibam, Mukalla or other places in Hadhramaut.

DNA

Very few researches and DNA samples, if any, have been done on Arab-Indonesians. It has been guessed that the DNA haplogroups found among Arab Indonesians are J, L and R[34] with higher possibility of J-M267 traces.[35] Haplogroup G-PF3296 is also common, especially among descents of Sayyids of Hadhramaut.[36] It is predicted the presence of mtDNA R9 haplogroups among Arab Indonesians due to mixed marriage between Indonesians and Yemenis.

Notable Arab Indonesians

- Abdurrahman Baswedan, diplomat, Indonesian freedom fighter and the founder of Persatoean Arab-Indonesia[12][37]

- Abu Bakar Bashir, suspected head of Jemaah Islamiyah[12]

- Ahmad Albar, rock singer[38]

- Ahmad Surkati of Sudan, founder of al-Irsyad.[22]

- Ali Alatas (half-Sundanese), former Minister of Foreign Affairs[12]

- Alwi Shihab (half-Buginese), special envoy for the Middle East[39][40]

- Anies Baswedan, educator, Minister of Education (2014–2016), Governor of Jakarta (2017–2022)

- Fadel Muhammad, former governor of Gorontalo and Deputy Speaker of People's Consultative Assembly

- Fuad Hassan, minister of education and culture

- Habib Ali Kwitang, Islamic cleric and founder of the Islamic Center of Indonesia[41]

- Usman bin Yahya, Mufti of Batavia[42]

- Habib Munzir Al-Musawa, preacher[43]

- Haddad Alwi, Nasheed singer[44]

- Haidar Bagir, scholar and businessman[45]

- Hamid Algadri, figure in the Indonesian National Revolution and member of parliament[46]

- Jafar Umar Thalib, founder of Laskar Jihad[47]

- Muhammad Rizieq Shihab, founder of FPI[48]

- Munir Said Thalib, Human Rights activist[49]

- Nurhayati Ali Assegaf, politician[50]

- Quraish Shihab (half-Buginese), Islamic scholar[39][40]

- Raden Saleh, painter in Dutch East Indies era[37]

- Said Naum, Kapitan Arab, a philanthropist[51]

- Syarif Hamid II of Pontianak, Sultan of Pontianak Sultanate

See also

Gallery

- Arab Indonesians

Indonesian Arab of Talise

Indonesian Arab of Talise_dan_HABIB_MUHAMAD_BIN_ALI_BIN_YAHYA.jpg.webp)

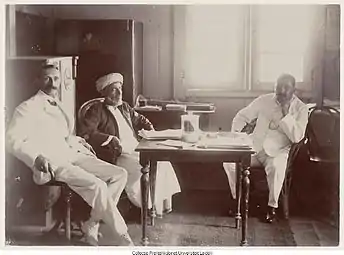

Kapten Arab of Tegal, Central Java

Kapten Arab of Tegal, Central Java Arab Indonesian from Surabaya

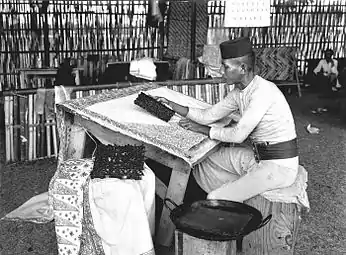

Arab Indonesian from Surabaya An Arab Indonesian working on batik wax stamps to work in Tanah Abang

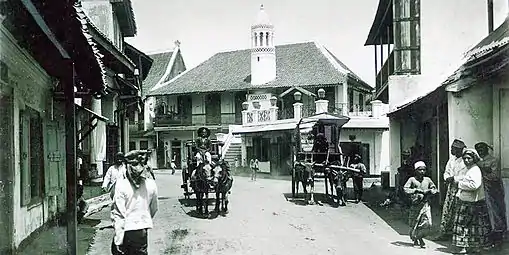

An Arab Indonesian working on batik wax stamps to work in Tanah Abang Hadhrami Arab neighborhood in Ampel, Surabaya, 1880

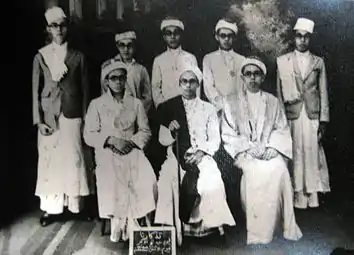

Hadhrami Arab neighborhood in Ampel, Surabaya, 1880 hadrami People on Eid al-Adha day in Palembang, February 1937 CE

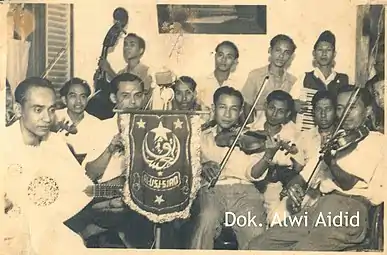

hadrami People on Eid al-Adha day in Palembang, February 1937 CE Arab-Indonesian musicians in Jakarta, 1949

Arab-Indonesian musicians in Jakarta, 1949

References

Footnotes

- Aris Ananta, Evi Nurvidya Arifin, M Sairi Hasbullah, Nur Budi Handayani, Agus Pramono (July 14, 2015). "Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity (Table 4.38 The 145 Ethnic Groups: Indonesia, 2010)". Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Leo Suryadinata (2008). Ethnic Chinese in Contemporary Indonesia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 29. ISBN 978-981-230-835-1.

- Shahab, Alwi (January 21, 1996). "Komunitas Arab Di Pekojan Dan Krukut: Dari mayoritas Menjadi Minoritas" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on August 9, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- Kartini, Raden Ajeng (1899). "Het Huwelijk bij de Kodjas". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). 50 (3/4, #6, part 6): 695–702. JSTOR 25738623.

- Rumphius, Georg Eberhard (1743). Burmanni, Joannis (ed.). Herbarium Amboinense (in Latin and Dutch). Vol. 3. Amsterdam: apud Fransicum Changuion, Joannem Catuffe, Hermannum Uytwerf. pp. 160–162, Tab.C. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.569. note the work was also published in the Hague and Utrecht simultaneously by others.

- Al Qurtuby, Sumanto (July 15, 2017). "Arabs and "Indo-Arabs" in Indonesia: Historical Dynamics, Social Relations and Contemporary Changes". International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies. 13 (2): 45–72. doi:10.21315/ijaps2017.13.2.3. ISSN 1823-6243.

- Suryadinata 2008.

- van der Kroef, Justus M. (1953). "The Arabs in Indonesia". Middle East Journal. 7 (3): 300–323. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322510.

- Hudson, Violet. "The hallucinatory history of nutmeg". Spectator life (Dictionary of food). Spectator life. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- Ricklefs, M. C.; Lockhart, Bruce; Lau, Albert; Reyes, Portia; Aung-Thwin, Maitrii (November 19, 2010). A New History of Southeast Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137015549.

- W.P. Groeneveldt, 1877, Notes on the Malay Archipelago and Malacca, Batavia : W. Bruining.

- Cribb & Kahin 2004, pp. 18–19.

- Graf, Arndt; Schroter, Susanne; Wieringa, Edwin (2010). Aceh: History, Politics and Culture. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814279123.

- Boxberger, Linda (February 1, 2012). On the Edge of Empire: Hadhramawt, Emigration, and the Indian Ocean, 1880s–1930s. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791489352.

- Jacobsen 2009, p. 54.

- Freitag 2003, pp. 237–239.

- Jacobsen 2009, pp. 54–55.

- Jacobsen 2009, pp. 21–22.

- Diederich 2005, p. 140.

- Fealy 2004, pp. 109–110.

- Suryadinata 2008, p. 32.

- Mobini-Kesheh, Natalie (1999). The Hadrami Awakening: Community and Identity in the Netherlands East Indies, 1900–1942 (illustrated ed.). EAP Publications. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-08772-77279.

- Suryadinata 2008, p. 29.

- Shihab, Alwi (December 21, 2003). "Hadramaut dan Para Kapiten Arab". Republika. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- Suryadinata 2008, pp. 29–30.

- Jacobsen 2009, p. 19.

- Jacobsen 2009, p. 21.

- Weintraub, Andrew N. (April 20, 2011). Islam and Popular Culture in Indonesia and Malaysia. Routledge. ISBN 9781136812286.

- World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia. Vol. 10. Marshall Cavendish. 2007. ISBN 9780761476436.

- "Ka'ak; Jamu Khas Arab". Antara. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

- "Maraq [Yemeni Soup]". January 16, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

- "Gulai ala Arab Sesegar Kuah Sup Buntut" (in Indonesian). August 7, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

- Jacobsen 2009.

- Karafet; et al. (March 5, 2010). "Major East–West Division Underlies Y Chromosome Stratification across Indonesia". Molecular Biology and Evolution. Oxford University Press. 27 (8): 1833–44. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq063. PMID 20207712.

- Chiaroni; et al. (October 14, 2009). "The emergence of Y-chromosome haplogroup J1e among Arabic-speaking populations". PMC 2987219.

- "Yemen Project مشروع اليمن – Y-DNA SNP".

- Algadri, Hamid (1994). Dutch Policy against Islam and Indonesians of Arab Descent in Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia: LP3ES. p. 187. ISBN 979-8391-31-4.

- Shahab, Alwi (2004). Saudar Baghdar dari Betawi (in Indonesian). Penerbit Republika. p. 25. ISBN 978-9793210308.

- Leifer, Michael (2001). Dictionary of the Modern Politics of South-East Asia (reprint, revised ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 243. ISBN 9780415238755.

- Backman, Michael (2004). The Asian Insider: Unconventional Wisdom for Asian Business. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 154. ISBN 9781403948403. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- bin Muhammad al-Habsyi, Abdurrahman (2010). Prasetyo Sudrajat (ed.). Sumur yang Tak Pernah Kering: Dari Kwitang Menjadi Ulama Besar: Riwayat Habib Ali Alhabsyi Kwitang (PDF) (in Indonesian). ICI. ISBN 978-6029668308. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- Syamsu As, Muhammad (1996). Ulama Pembawa Islam Di Indonesia Dan Sekitarnya. Seri Buku Sejarah Islam (in Indonesian). Vol. 4 (2 ed.). Lentera. ISBN 978-9798880162.

- Morimoto, Kazuo, ed. (2012). Sayyids and Sharifs in Muslim Societies: The Living Links to the Prophet. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136337383.

- Weintraub, Andrew N., ed. (2011). lam and Popular Culture in Indonesia and Malaysia. Routledge. ISBN 9781136812293. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- van der Velde, Paul; McKay, Alex, eds. (1998). New Developments in Asian Studies: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-710306067. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- Legge, J. D. (2010). Intellectuals and Nationalism in Indonesia: A Study of the Following Recruited by Sutan Sjahrir in Occupied Jakarta (reprint ed.). Equinox Publishing. p. 79. ISBN 978-6-028397230.

- Bunte, Marco; Ufen, Andreas, eds. (2008). Democratization in Post-Suharto Indonesia. Routledge. p. 286. ISBN 9781134070886. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- L. Berger, Peter; Redding, Gordon (2011). The Hidden Form of Capital: Spiritual Influences in Societal Progress (illustrated ed.). London, UK: Anthem Press. p. 195. ISBN 9780857284136.

- "Komisi Untuk Orang Hilang dan Tindak Kekerasan (Indonesia)". Bunuh Munir!: sebuah buku putih. Komisi Untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan. 2006 [October 14, 2008]. ISBN 9789799822567.

- "Dipanggil Arab, Nurhayati Perkarakan Ruhut ke Dewan Kehormatan PD". Merdeka Daily. June 24, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- "Ulama Hadhrami di Tanah Betawi Berdakwah dengan Sepenuh Hati" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

Bibliography

- Cribb, Robert; Kahin, Audrey (2004). Historical Dictionary of Indonesia. Historical dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4935-8.

- Diederich, Mathias (2005). "Indonesians in Saudi Arabia: Religious and Economic Connections". In Al-Rasheed, Madawi (ed.). Transnational Connections and the Arab Gulf. London: Rutledge. pp. 128–146. ISBN 978-0-203-39793-0.

- Fealy, Greg (2004). "Islamic Radicalism in Indonesia: The Faltering Revival?". Southeast Asian Affairs. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 2004: 104–124. doi:10.1355/SEAA04H. ISBN 9789812302397. ISSN 0377-5437. S2CID 154594043.

- Freitag, Ulrike (2003). Indian Ocean Migrants and State Formation in Hadhramaut: Reforming the Homeland. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12850-7.

- Jacobsen, Frode (2009). Hadrami Arabs in Present-day Indonesia : an Indonesia-oriented Group with an Arab Signature. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-48092-5.

- Suryadinata, Leo (2008). Ethnic Chinese in Contemporary Indonesia. Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centre and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-230-835-1.