Iban people

The Ibans or Sea Dayaks are an Austronesian ethnic group indigenous to the state of Sarawak and some parts of Brunei and West Kalimantan, Indonesia. The Ibans are also known as Sea Dayaks and the title Dayak was given by the British and the Dutch to various ethnic groups in Borneo island. It is believed that the term "Iban" was originally an exonym used by the Kayans, who – when they initially came into contact with them – referred to the Sea Dayaks in the upper Rajang river region as the "Hivan".

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approximately 1,500,000+ | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Borneo: | |

| 964,885[1] | |

| 23,500[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Iban (predominantly), English, the Malay language dialect of Sarawak Malay | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Catholicism and Mainly Anglicanism), Animism, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kantu, Mualang, Semberuang, Bugau, Sebaru | |

Ibans were renowned for practicing headhunting and territorial migration, and had a fearsome reputation as a strong and successfully warring tribe. Since the arrival for Europeans and the subsequent colonisation of the area, headhunting gradually faded out of practice, although many other tribal customs and practices as well as the Iban language continue to thrive. The Iban population is concentrated in the state of Sarawak in Malaysia, Brunei, and the Indonesian province of West Kalimantan. They traditionally live in longhouses called rumah panjai or betang (trunk) in West Kalimantan.[3][4]

History

Early origins

The Iban people of Borneo possess an indigenous account of their history, mostly in oral literature,[5] partly in writing in papan turai (wooden records),[6] and partly in common cultural customary practices.[7]

According to native myths and legend, they historically came from Batang Lupar river in Sarawak (Malaysian Borneo). Batang Lupar is their first settlement known as Tembawai Satu based on their legends. They slowly moved to all parts of western and northern Borneo due to tribal migration. Their last migration was Kapuas River in Indonesia which is known as Tembawai Tujoh.[8][9][10]

The Iban migrations from Kapuas to Sarawak

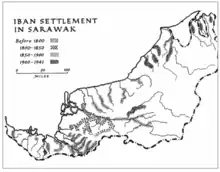

Based on the research conducted by Benedict Sandin (1968). The period of Iban migrations from the Kapuas Hulu Range were determined to commenced from the 1750s.[11] These settlers were identified to enter Batang Lupar and established settlement adjacent to the Undop River. In the period of five generations, they expanded towards west, east and north, founding new settlements within the tributaries of Batang Lupar, Batang Sadong, Saribas and Batang Layar.

By the 19th century during the Brooke administration, the Ibans started to migrate towards the basin of Rejang via the upper reach of Katibas River, Batang Lupar and Saribas River. From 1870s, it was recorded that a huge populations of Ibans have established near Mukah and Oya River. The settlers arrived to Tatau, Kemena (Bintulu) and Balingan by the 1900s. In the turn of twentieth century, the Iban expanded to the Limbang River and Baram valley in the northern Sarawak.

Based on the colonial accounts, the migrations during the Brooke rule has generated several complications in the state, as the Ibans can easily exceeded the other pre-existing tribes and caused an unfavorable environmental impact on the land areas originally designated for swidden agriculture. Thus, they were prohibited by the authorities to emigrate towards other river systems. The tension between the Brooke administration and the Ibans were recorded in Balleh Valley.[12]

Despite the fact that the early migration has had created challengers for Brooke administration, it conversely have introduced a favorable circumstances. The Ibans and their wide knowledge on the land and forest produce were promoted by Brooke to explore to the new areas to seek rattans, camphor, damar, wild rubber and other natural products. The authority also support perpetual Iban settlements in the newly ceded areas of Sarawak. This can be seen during the 1890 annexation of Limbang where the Sarawak government trusting on the Ibans to aid its authority. A similar process was also took place in Baram.[13]

By the end of 1800s, several areas in Sarawak including Batang Lupar, Skrang Valley and Batang Ai were experiencing an overpopulation. With several conditions, the Sarawakian government opened several territories for the Iban community. For instance, the government granted the Simanggang Ibans an unlimited migrations towards Bintulu, Baram and Balingan. While in the early 20th century, the Ibans from the Second Division of Sarawak was allowed to emigrate to Limbang, and the government additionally helped the movement of Ibans to Lundu from Batang Lupar.[14]

The government sponsored policy has left a positive impact on the spread of Iban language and culture throughout Sarawak. Nonetheless, the migrations also have effected other groups as well, as in the case of the Bukitans in Batang Lupar, where the process of intermarriage by the Bukitan leaders has slowly stimulated the whole Batang Lupar Bukitan populations to adopt the Iban way of life, thus assimilating the ethnic into the Iban community. There are also some other groups having a more hostile relationship, as in the case of Ukits, Seru, Miriek and Biliun where the populations were almost totally replaced by the Ibans.[15]

18th–19th century

The colonial accounts and reports of Dayak activity in Borneo detail carefully cultivated economic and political relationships with other communities as well as an ample body of research and study concerning the history of Dayak migrations.[16] In particular, the Iban or the Sea Dayak exploits in the South China Seas are documented, owing to their ferocity and aggressive culture of war against sea-dwelling groups and emerging Western trade interests in the 18th and 19th centuries.[17]

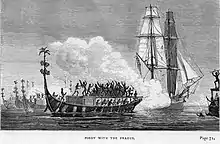

In 1838, adventurer James Brooke arrived in the region to find the Sultan of Brunei in a desperate attempt to suppress a rebellion against his rule. Brooke aided the Sultan in putting down the rebellion, for which he was made Governor of Sarawak in 1841, being granted the title of Rajah. Brooke undertook operations to suppress Dayak piracy, establishing a secondary objective to put an end to their custom of headhunting as well. During his tenure as Governor, Brooke's most well-known Dayak opponent was the military commander Rentap; Brooke led three expeditions against him and finally defeated him at the Battle of Sadok Hill. During the expeditions, Brooke employed numerous Dayak troops, quipping that "only Dayaks can kill Dayaks".[18] Brooke became embroiled in controversy in 1851 when accusations against him of excessive usage of force against the Dayaks, under the guise of anti-piracy operations, ultimately led to the appointment of a Commission of Inquiry in Singapore in 1854. After an investigation, the Commission dismissed the charges.[19] Brooke employed his Dayak troops during other military expeditions, such as those against the Chinese Sarawakian insurgent Liu Shan Bang and Malay Sarawakian Sharif Masahor.[20][21]

After mass conversions to Christianity and anti-headhunting legislation by the European administrations was passed, the practice was banned and appeared to have disappeared. However, the Brooke-led Sarawak government, although banning unauthorized headhunting, allowed "ngayau" headhunting practices by the Brooke-supporting natives during military expeditions against rebellions throughout the state, thereby never really extinguishing the spirit of headhunting especially among the Iban natives. The state-sanctioned troops were allowed to take heads, properties like jars and brassware, burn houses and farms, exempted from paying door taxes, and in some cases, granted new territories to migrate into. This Brooke's practice was in remarkable contrast to the practice by the Dutch in the neighbouring West Kalimantan who prohibited any native participation in its punitive expeditions. Initially, James Brooke (the first Rajah of Sarawak) did engage his small navy in the Battle of Beting Maru against the Iban and Malay of the Saribas region and the Iban of Skrang under Rentap's charge but this resulted in the Public Inquiry by the colonial government in Singapore. Thereafter, the Brooke government gathered a local troop who were its allies.

20th century

During the Second World War, Japanese forces occupied Borneo and treated all of the indigenous peoples poorly – massacres of the Malay and Dayak peoples were common, especially among the Dayaks of the Kapit Division.[22] In response, the Dayaks formed a special force to assist the Allied forces. Eleven US airmen and a few dozen Australian special operatives trained a thousand Dayaks from the Kapit Division in guerrilla warfare. This army of tribesmen killed or captured some 1,500 Japanese soldiers and provided the Allies with vital intelligence about Japanese-held oil fields.[23]

During the Malayan Emergency, the British Army employed Iban headhunters against the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA). Typically two would be attached to each infantry patrol as trackers and general assistants, acting as the platoon commander's eyes and ears in this deeply alien environment.[24] News of this was exposed to the public 1952 when the British communist newspaper called The Daily Worker published multiple photographs of Ibans and British soldiers posing with the severed heads of suspected MNLA members.[25] Initially, the British government denied allowing Iban troops to practise headhunting against the MNLA, until Colonial Secretary Oliver Lyttleton confirmed to Parliament that the Ibans were indeed granted such a right to do so. All Dayak troops were disbanded upon the end of the conflict.[26]

Ibanic Dayak regional groups

Although Ibans generally speak various dialects which are mutually intelligible, they can be divided into different branches which are named after the geographical areas where they reside.

| Sub-ethnic group | Regions with significant population | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Kantu’ | Upper Kapuas, West Kalimantan[27] | |

| Ketungau (Sebaru’, Demam) | Ketungau River, West Kalimantan | |

| Mualang | Belitang River, West Kalimantan | |

| Seberuang | Seberuang and Suhaid Rivers, West Kalimantan | |

| Desa | Sintang, West Kalimantan | |

| Iban | Lake Sentarum, West Kalimantan | |

| Bugau | Kalimantan–Sarawak border | |

| Ulu Ai/batang ai | Lubok Antu, Sarawak | The first region settled by the Ibans in Sarawak after their migration from Kapuas, West Kalimantan.[28] |

| Remuns | Serian, Sarawak | |

| Sebuyaus | Lundu and Samarahan, Sarawak | |

| Balaus | Sri Aman, Sarawak | |

| Saribas | Betong, Saratok and parts of Sarikei, Sarawak | |

| Undup | Undup, Sarawak | |

| Rajang/Bilak Sedik | Rajang River, Sibu, Kapit, Belaga, Kanowit, Song, Sarikei, Bintangor, Bintulu, Limbang, Lawas and Miri, Sarawak Belait and Temburong, Brunei |

The largest Iban sub-ethnic group |

| Merotai | Tawau, Sabah |

Language and oral literature

The Iban language (jaku Iban) is spoken by the Iban, a branch of the Dayak ethnic group formerly known as "Sea Dayak". The language belongs to Malayic languages, which is a Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. It is thought that the homeland of the Malayic languages is in western Borneo, where the Ibanic languages remain. The Malayic branch represents a secondary dispersal, probably from central Sumatra but possibly also from Borneo.[29]

The Iban people speak basically one language with regional dialects that vary in intonation. They have a rich oral literature, as noted by Vincent Sutlive when meeting Derek Freeman, a professor of anthropology at the Australian National University who stated: Derek Freeman told me that Iban folklore "probably exceeds in sheer volume the literature of the Greeks. At that time, I thought Freeman excessive. Today, I suspect he may have been conservative in his estimate (Sutlive 1988: 73)." There is a body of oral poetry which is recited by the Iban depending on the occasion.

Nowadays, the Iban language is mostly taught at schools with Iban students in town and rural areas in Indonesia and Malaysia. The Iban language is included in Malaysian public school examinations for Form 3 and Form 5 students. Students comment that questions from these exams can be daunting, since they mostly cover the classic Iban language, while students are more fluent in the contemporary tongue.

Iban ritual festivals and rites

Significant traditional festivals, or gawai, to propitiate the gods, can be grouped into seven categories according to the main ritual activities:

- Farming-related festivals for the deity of agriculture, Sempulang Gana

- War-related festivals to honour the deity of war, Sengalang Burong

- Fortune-related festivals dedicated to the deity of fortune, Anda Mara

- Procreation-related festival (Gawai Melah Pinang) for the deity of creation, Selampandai

- Health-related festivals for the gods of Shamanism, Menjaya and Ini Andan

- Death-related festival (Gawai Antu or Ngelumbong), including rituals to invite dead souls to their final separation from the living

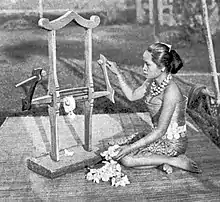

- Weaving-related festival (Gawai Ngar) for patrons of weaving

For simplicity and cost savings, some of the gawai have been relegated into the medium category of propitiation called gawa. These include Gawai Tuah into Nimang Tuah, Gawai Benih into Nimang Benih and Gawa Beintu-intu into their respective nimang category, wherein the key activity is the timang incantation by the bards. Gawai Matah can be relegated into a minor rite simply called matah. The first dibbling (nugal) session is normally preceded by a medium-sized offering ceremony in which kibong padi (a paddy's net) is erected with three flags. The paddy's net is erected by splitting a bamboo trunk lengthwise into four pieces with the tips inserted into the ground. Underneath the paddy's net, baskets or gunny sacks hold all the paddy seeds. Then men distribute the seeds to a line of ladies who place them into dibbled holes.

Often festivals are celebrated by the Iban today based on needs and economy. These include Sandau Ari (Mid-Day Rite), Gawai Kalingkang (Bamboo Receptacle Festival), Gawai Batu (Whetstone Festival), Gawai Tuah (Fortune Festival) and Gawai Antu (Festival for the Dead Relatives), which can be celebrated without the timang jalong (ceremonial cup chanting), reducing its size and cost.

Commonly, all those festivals are celebrated after rice harvesting near the end of May. At harvest time, there is plenty of food for feasting. Not only is rice plentiful, but also poultry, pigs, chickens, fish, and jungle meats around this time. Therefore, it is fitting to collectively call this festive season among Dayak as the Gawai Dayak festival. It is celebrated every year on 1 and 2 June, at the end of the harvest season, to worship the Lord Sempulang Gana and other gods. On this day, the Iban visit family and friends and gather to celebrate. It is the right timing for a new year resolution, turn around, adventures, projects or sojourns. These new endeavours and undertakings are initiatives or activities under a popular practice known as 'bejalai', 'belelang' or 'pegi'.

Iban Religion

Iban or Sea Dayaks have its own traditional religious system called "pengarap Iban". The Encyclopedia of Iban Studies (2001) states that:

“The Iban lexeme petara or betara is a loan from Sanskrit, ‘pitr, ‘ancestors” (Richards 1981:281) [q.q]) or pitarah, the name of a Hindu deity. There are at least two, possibly three, categories of gods under the pantheon of the Iban religion. First, there are creator gods, beings who in the beginning brought into being land, sky, water, and human beings. Second, there are principal gods whose functions are crucially important to human activities and survival. Finally, there are the mythic culture heroes or spirit heroes, whose adventures involve and influence the affairs of Iban men and women. These categories of deities illustrate difficulties in achieving consensus regarding projected beings.

The unified pantheon of the Iban religion is headed by Petara who is the supreme deity or principal God, Raja petara, also known as Entala or Keri Raja petara. This supreme God heads the creator gods who are Seragindah who creates land, Seragindi who creates water and Seragindit who creates the sky.

According to Benedict Sandin his book of Iban Adat and Augury, under the same supreme God, there are then seven gods of specific purpose including two sisters who are Pantan Ini’ Andan (of the sky as the god of justice) and Biku Indu’ Antu (of the earth as the god of worshipping)” (p. 1458) and five brothers namely Sengalang Burong (god of war), Sempulang Gana (god of agriculture), Selampandai Selampeta Selampetoh (god of smithing), Menjaya (god of shamanism) and Anda Mara (god of fortune). These seven gods are known as the Orang Raja Durong who descended from Raja Chananum Raja Chanuda. Among others, the famous cultural heroes and heroines of the Orang Panggau and Gelong who descended from Tambai Chiri are Keling, Laja and Sempurai and Kumang, Lulong and Indai Abang. These gods and heroes appear to human beings in dreams and in augury bird, animal and snake forms in this world.

James Jemut Masing in his PhD thesis of The Coming Of Gods states that to worship this pantheon, there are three categories of propitiatory ceremonies under the Iban religion i.e. bedara (offerings of ascending order), gawa (chanting of various kinds) and gawai (elaborate ritual festival of ascending degrees). Derek Freeman in his paper of Iban Augury states that divination among Iban can be achieved via five methods: dream, pig liver commentary, deliberate augury seeking, chance augury encounter and solitude. Clifford Sather in his article of Iban Longhouse: Posts and Hearths states that the longhouse acts as both accommodation and ritual space.

Culture and customs

Kinship in Dayak society is traced in both lines of genealogy (tusut). Although in Dayak Iban society, men and women possess equal rights in status and property ownership, the political office has strictly been the occupation of the traditional Iban patriarch. There is a council of elders in each longhouse.

Overall, Dayak leadership in any given region is marked by titles, a Penghulu for instance would have invested authority on behalf of a network of Tuai Rumah's and so on to a Pemancha, Pengarah to Temenggung in the ascending order while Panglima or Orang Kaya (Rekaya) are titles given by Malays to some Dayaks.

Individual Dayak groups have their social and hierarchy systems defined internally, and these differ widely from Ibans to Ngajus and Benuaqs to Kayans.

In Sarawak, Temenggong Koh Anak Jubang was the first paramount chief of Dayaks in Sarawak and was followed by Tun Temenggong Jugah Anak Barieng who was one of the main signatories for the formation of the Federation of Malaysia between Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak with Singapore expelled later on. He was said to be the "bridge between Malaya and East Malaysia".[18] The latter was fondly called "Apai" by others, which means father. He received no western or formal education.

The most salient feature of Dayak social organisation is the practice of Longhouse domicile. This is a structure supported by hardwood posts that can be hundreds of metres long, usually located along a terraced river bank. At one side is a long communal platform, from which the individual households can be reached.

The Iban of the Kapuas and Sarawak have organised their Longhouse settlements in response to their migratory patterns. Iban longhouses vary in size, from those slightly over 100 metres in length to large settlements over 500 metres in length. Longhouses have a door and apartment for every family living in the longhouse. For example, a longhouse of 200 doors is equivalent to a settlement of 200 families.

The tuai rumah (longhouse chief) can be aided by a tuai burong (bird leader), tuai umai (farming leader), and a manang (shaman). Nowadays, each longhouse will have a Security and Development Committee and ad hoc committee will be formed as and when necessary for example during festivals such as Gawai Dayak.

The Dayaks are peace-loving people who live based on customary rules or adat asal which govern each of their main activities. The adat is administered by the tuai rumah aided by the Council of Elders in the longhouse so that any dispute can be settled amicably among the dwellers themselves via berandau (discussion). If no settlement can be reached at the longhouse chief level, then the dispute will escalate to a more senior leader in the region or pengulu (district chief) level in modern times and so on.

Among the main sections of customary adat of the Iban Dayaks are as follows:

- Adat berumah (House building rule)

- Adat melah pinang, butang ngau sarak (Marriage, adultery, and divorce rule)

- Adat beranak (Childbearing and raising rule)

- Adat bumai and beguna tanah (Agricultural and land use rule)

- Adat ngayau (Headhunting rule) and adapt ngintu anti Pala (head skull keeping)

- Adat ngasu, berikan, ngembuah and napang (Hunting, fishing, fruit and honey collection rule)

- Adat tebalu, ngetas ulit ngau beserarak bungai (Widow/widower, mourning and soul separation rule)

- Adat begawai (festival rule)

- Adat idup di rumah panjai (Order of life in the longhouse rule)

- Adat betenun, main lama, kajat ngau taboh (Weaving, past times, dance and music rule)

- Adat beburong, bemimpi ngau becenaga ati babi (Bird and animal omen, dream and pig liver rule)

- Adat belelang (Journey rule)[30]

The Dayak life centres on the paddy planting activity every year. The Iban Dayak has their own year-long calendar with 12 consecutive months which are one month later than the Roman calendar. The months are named in accordance with the paddy farming activities and the activities in between. Other than paddy, also planted in the farm are vegetables like ensabi, pumpkin, round brinjal, cucumber, corn, lingkau and other food sources like tapioca, sugarcane, sweet potatoes and finally after the paddy has been harvested, cotton is planted which takes about two months to complete its cycle. The cotton is used for weaving before commercial cotton is traded.

Fresh lands cleared by each Dayak family will belong to that family and the longhouse community can also use the land with permission from the owning family. Usually, in one riverine system, a special tract of land is reserved for the use by the community itself to get natural supplies of wood, rattan, and other wild plants which are necessary for building houses, boats, coffins, and other living purposes, and also to leave living space for wild animals which is a source of meat.

Besides farming, Dayaks plant fruit trees like kepayang, dabai, rambutan, langsat, durian, isu, nyekak, and mangosteen near their longhouses or on their land plots to mark their ownership of the land. They also grow plants that produce dyes for colouring their cotton treads if not taken from the wild forest. Major fishing using the tuba root is normally done by the whole longhouse as the river may take some time to recover. Any wild meat obtained will be distributed according to a certain customary law which specifies the game catcher will the head or horn and several portions of the game while others would get an equally divided portion each. This rule allows every family a chance to supply meat which is the main source of protein.

Headhunting was an important part of the Dayak culture, in particular to the Iban and Kenyah. The origin of headhunting in Iban Dayaks can be traced to the story of a chief name Serapoh who was asked by a spirit to obtain a fresh head to open a mourning jar but unfortunately killed a Kantu boy which he got by exchanging with a jar for this purpose for which the Kantu retaliated and thus starting the headhunting practice.[31] There used to be a tradition of retaliation for old headhunts, which kept the practice alive. External interference by the reign of the Brooke Rajahs in Sarawak via "bebanchak babi" (peacemaking) in Kapit and the Dutch in Kalimantan Borneo via peacemaking at Tumbang Anoi curtailed and limited this tradition.

Apart from mass raids, the practice of headhunting was then limited to individual retaliation attacks or the result of chance encounters. Early Brooke Government reports describing Dayak Iban and Kenyah War parties with captured enemy heads. At various times, there have been massive coordinated raids in the interior and throughout coastal Borneo before and after the arrival of the Raj during Brooke's reign in Sarawak.

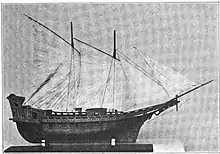

The Ibans' journey along the coastal regions using a large boat called "bandong" with sails made of leaves or cloths may have given rise to the term, Sea Dayak, although, throughout the 19th century, Sarawak Government raids and independent expeditions appeared to have been carried out as far as Brunei, Mindanao, East coast Malaya, Jawa and Celebes.

Tandem diplomatic relations between the Sarawak Government (Brooke Rajah) and Britain (East India Company and the Royal Navy) acted as a pivot and a deterrence to the former's territorial ambitions, against the Dutch administration in the Kalimantan regions and client sultanates.

Religion and belief

For hundreds of years, the Iban's ancestors practiced their own traditional custom and pagan religious system. European Christian colonial invaders, after the arrival of James Brooke, led to the influence of European missionaries and conversions to Christianity. Although the majority are now Christian; many continue to observe both Christian and traditional pagan ceremonies, particularly during marriages or festivals, although some ancestral practices such as 'Miring' are still prohibited by certain churches. After being Christianized, the majority of Iban people have changed their traditional name to a Hebrew-based "Christian name" followed by the Ibanese name such as David Dunggau, Joseph Jelenggai, Mary Mayang, etc.

For the majority of Ibans who are Christians, some Christian festivals such as Christmas, Good Friday, Easter are also celebrated. Some Ibans are devout Christians and follow the Christian faith strictly. Since conversion to Christianity, some Iban people celebrate their ancestors' pagan festivals using Christian ways and the majority still observe Gawai Dayak (the Dayak Festival), which is a generic celebration in nature unless a gawai proper is held and thereby preserves their ancestors' culture and tradition.

In Brunei, 1,503 Ibans have converted to Islam from 2009 to 2019 according to official statistics. Many Bruneian Ibans intermarry with Malays and convert to Islam as a result. Nevertheless, most Iban in Brunei are devout Christians similar to the Iban in Malaysia. Bruneian Ibans also often intermarry with the Murut or Christian Chinese due to their shared faith.[33][34]

Despite the difference in faiths, Ibans of different faiths do live and help each other regardless of faith but some do split their longhouses due to different faiths or even political affiliations. The Ibans believe in helping and having fun together. Some elder Ibans are worried that among most of the younger Iban generation, their culture has faded since the conversion to Christianity and the adoption of a more modern life style. Nevertheless, most Iban embrace modern progress and development.

Many Christian Dayaks have adopted European names, but some continue to maintain their ancestors' traditional names. Since the conversion of most Iban people to Christianity, some have generally abandoned their ancestors' beliefs such as 'Miring' or the celebration of 'Gawai Antu', and many celebrate only Christianized traditional festivals.

Numerous local people and certain missionaries have sought to document and preserve traditional Dayak religious practices. For example, Reverend William Howell contributed numerous articles on the Iban language, lore, and culture between 1909 and 1910 to the Sarawak Gazette. The articles were later compiled in a book in 1963 entitled, The Sea Dayaks and Other Races of Sarawak.[35]

Cuisine

Pansoh or lulun is a dish of rice or other food cooked in cylindrical bamboo sections (ruas) with the top end cut open to insert the food while the bottom end remains uncut to act as a container. A middle-aged bamboo tree is normally chosen to make containers because its wall still contains water; old, mature bamboo trees are dryer and are burned by fire more readily. The bamboo also imparts the famous and addictive, special bamboo taste or flavour to the cooked food or rice. Glutinous rice is often cooked in bamboo for the routine diet or during celebrations. It is believed in the old days, bamboo cylinders were used to cook food in the absence of metal pots.

Kasam is preserved meat, fish or vegetable. In the absence of refrigerators, jungle meat from wild game, river fish or vegetable are preserved by cutting them into small pieces and mixing them with salt before placing them in a ceramic jar or today, glass jars. Ceramic jars were precious in the old days as food, tuak or general containers. Meat preserved in this manner can last for at least several months. Preserved meats are mixed with 'daun and buah kepayang' (local leaf and nut).

.jpg.webp)

Tuak is an Iban wine traditionally made from cooked glutinous rice (asi pulut) mixed with home-made yeast (ciping) containing herbs for fermentation. It is used to serve guests, especially as a welcoming drink when entering a longhouse. However, these raw materials are rarely used unless available in large quantities. Tuak and other types of drinks (both alcoholic and non-alcoholic) can be served in several rounds during a ceremony called nyibur temuai (serving drinks to guests) as a ai aus (thirst quenching drink), a ai basu kaki (foot washing drink), a ai basa (respect drink) and a ai untong (profit drink).

Another type of stronger alcoholic drink is called langkau (hut) or arak pandok (cooked spirit). It contains a higher alcohol content because it is actually made of tuak which has been distilled over fire to boil off the alcohol, cooled and collected into containers.

Besides, the Iban like to preserve foods by smoking them over the hearth. Smoked foods are called 'salai'. These can be eaten directly or cooked, perhaps with vegetables.

The Iban traditional cakes are called 'penganan', and 'tumpi' (deep fried but not hardened) and chuwan' and 'sarang semut' (deep fried to harden and to last long).

The Iban will cook glutinous rice in bamboo containers or wrapped in leaves called 'daun long'.

During the early rice harvesting, the Iban like to make 'kemping padi' (something like oat).

Music

Iban music is percussion-oriented. The Iban have a musical heritage consisting of various types of agung ensembles – percussion ensembles composed of large hanging, suspended or held, bossed/knobbed gongs which act as drums without any accompanying melodic instrument. The typical Iban agung ensemble will include a set of engkerumung (small gongs arranged together side by side and played like a xylophone), a tawak (the so-called "bass gong"), a bebendai (which acts as a snare) and also a ketebung or bedup (a single sided drum/percussion instrument).

One example of Iban traditional music is the taboh.[36] There are various kinds of taboh (music), depending the purpose and types of ngajat, like alun lundai (slow tempo). The gendang can be played in some distinctive types corresponding to the purpose and type of each ceremony. The most popular ones are called gendang rayah (swinging blow) and gendang pampat (sweeping blow).

Sape is originally a traditional music by Orang Ulu (Kayan, Kenyah and Kelabit). Nowadays, both the Iban as well as the Orang Ulu Kayan, Kenyah and Kelabit play an instrument resembling the guitar called the sape. Datun Jalut and nganjak lansan are the most common traditional dances performed accompanied by a sape tune. The sape is the official musical instrument of the Malaysian state of Sarawak. It is played similarly to the way rock guitarists play guitar solos, albeit a little slower, but not as slow as the blues.[37]

Handicrafts

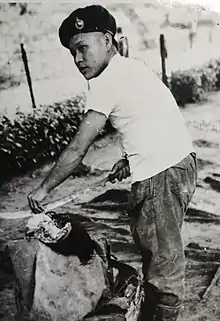

Traditional carvings (ukir) include: hornbill effigy carving, the terabai shield, the engkeramba (ghost statue), the knife handle, normally made of deer horn, the knife scabbard, decorative carving on the metal blade itself during ngamboh blacksmithing e.g. butoh kunding, bamboo stoves, bamboo containers and frightening masks. Another related category is designing motives either by engraving or drawing with paints on wooden planks, walls or house posts. Even traditional coffins may be beautifully decorated using both carving and ukir-painting. The Iban plaits good armlets or calvelets called 'simpai'.

The Ibans like to tattoo themselves all over their bodies. There are motifs for each part of the body. The purpose of the tattoos is to protect the tattoo bearer or to signify certain events in their life. Some motifs are based on marine lives such as the crayfish (rengguang), prawn (undang) and crab (ketam), while other motifs are based on dangerous creatures like the cobra (tedong), scorpion (kala), ghost dog (pasun) and dragon (naga).

Other important motifs of body tattoo include items or events which are worth commemorating and experienced or encountered by Iban during a sojourn or adventure such as an aeroplane which may be tattooed on the chest. Some Ibans call this art of tattooing kalingai or ukir. To signify that an individual has killed an enemy (udah bedengah), he is entitled to tattoo his throat (engkatak) or his upper-side fingers (tegulun). Some traditional Iban do have piercings of the penis (called palang) or the ear lobes. The Iban will tattoo their body as a whole in a holistic design, not item by item in an uncoordinated manner.

Woven products are known as betenun. Several types of woven blankets made by the Ibans are pua kumbu, pua ikat, kain karap and kain sungkit.[38] Using weaving, the Iban make blankets, bird shirts (baju burong), kain kebat, kain betating and selampai. Weaving is the women's warpath while kayau (headhunting) is the men's warpath. The pua kumbu blanket do have conventional or ritual motives depending on the purpose of the woven item. Those who finish the weaving lessons are called tembu kayu (finish the wood) [[39]]. Among well-known ritual motifs are Gajah Meram (Brooding Elephant), Tiang Sandong (Ritual Pole), Meligai (Shrine) and Tiang Ranyai.[40]

The Iban call this skill pandai beranyam — plaiting various items namely mats (tikai), baskets and hats. The Ibans weave mats of numerous types namely tikai anyam dua tauka tiga, tikai bebuah (motive mat),[41] tikai lampit made of rattan and tikai peradani made of rattan and tekalong bark. Materials to make mats are beban to make the normal mat or the patterned mat, rattan to make tikai rotan, lampit when the rattan splits sewn using a thread or peradani when criss-crossed with the tekalong bark, senggang to make perampan used for drying and daun biruto make a normal tikai or kajang (canvas) which is very light when dry.

The names of Iban baskets are bakak (medium-sized container for transferring, lifting or medium-term storage), sintong (a basket worn at the waist for carrying harvested paddy stocks), raga (small wedge-shaped basket hung over one shoulder), tubang (cylindrical backpack), lanji (tall cylindrical backpack with four strong spines) and selabit (cuboid-shaped backpack). The height of the tubang basket fits the height of the human backside while the height of the lanji basket will extend between the bottom and head of the human. Thus, the lanji can carry twice as much as the tubang, making the latter more versatile than the former. The selabit backpack is used to carry uneven shaped bulk items e.g. the game obtained from the forest.

Another category of plaiting which is normally carried out by men is to make fish traps called bubu gali, bubu dudok, engsegak and abau using betong bamboo splits except bubu dudok which is made from ridan which can be bent without breaking.

The Iban also make special baskets called garong for the dead during Gawai Antu with numerous feet to denote the rank and status of the deceased which indicates his ultimate achievement during his lifetime. The Iban also make pukat (rectangular net) and jala (conical net) after nylon ropes became available.

Iban have their own hunting apparatus which includes making panjuk (rope and spring trap), peti (bamboo blade trap) and jarin (deer net). Nowadays, they use shotguns and dogs for animal hunting. Dogs were reared by the Ibans in longhouses, especially in the past, for hunting (ngasu) purposes and warning the Iban of any approaching danger. Shotguns could and were purchased from the Brooke administration. The Ibans make their own blowpipes, and obtain honey from the tapang tree.

The Ibans can also make boats. Canoes for normal use are called perau, but big war boats are called bangkong or bong. A canoe is usually fitted with long paddles and a sail made of kajang canvas. It is said that bangkong is used to sail along the coasts of northern Borneo or even to travel across the sea, for example, to Singapore.

Besides that, the Ibans make various blades called nyabur (curved blade for slashing), ilang (triangular shaped, straight blade), pedang (long curved sword of equal with along its length), duku chandong (short knife for chopping), duku penebas (slashing blade), lungga (small blade for intricate handworks), sangkoh (spear), jerepang (multipointed hook), and sumpit (blowpipe) with poisonous laja tips. Seligi is a spear made of a natural strong and sharp material like aping palm. Some Iban are in blacksmithing although steel is bought through contact with the outside world.

Although silversmithing originates from the Embaloh, some Iban became skilled in this trade and made silverware for body ornaments. The Iban buy brass ware such as tawak (gong), bendai (snare) and engkerumong tabak (tray) and baku (small box) from other people because they do not have brass-smithing skills. The Iban make their own kacit pinang to split the areca nut and pengusok pinang to grind the split pieces of the areca nut. They also make ketap(finger-held blade) to harvest ripened paddy stalks and iluk (hand-held blade) to weed.

Longhouse

The traditional Iban live in longhouses (rumah panjang or rumah panjai).[42] The architecture of a longhouse along the longitude (length) is designed to imitate a standing tree with a trunk (symbolized by the central tiang pemun being erected first) in the middle point of the longhouse with a branch on the left and right hand size. The tree log or trunk used in the construction must be correctly jointed from their base to the tip. This sequence of base-tip is repeated along the left and right branches. At each joint, the trunk will be cut on the lower side at its base and on the upper side at its tip. So this sequence of lower-upper cut will be repeated at subsequent trunks until the end. On the side view of a longhouse, the architecture also imitates the standing tree design i.e. each central post of each family room has left and right branches. Therefore, each part of the longhouse must be maintained if the longhouse is to remain healthy like a natural tree living healthily.

The layout of a traditional longhouse of the Iban Dayak could be described as follows:

- A central wall runs along the length of the building approximately down the longitudinal axis of the building. The space along one side of the wall serves as a corridor running the length of the building while the other side is blocked from public view by the wall and serves as private areas.

- Behind this wall lie the private units, bilik, each with a single door for each family. These are separated from each other by walls of their own and contain the living and sleeping spaces for each family. The kitchens, dapor, may be situated within this private space but are nowadays often situated in rooms of their own, added to the back of a bilik or even in a building standing a little away from the longhouse and accessed by a small bridge. This separation prevents cooking fires from spreading to the living spaces, should they spread out of control, as well as reducing smoke and insects attracted to cooking from gathering in living quarters.[43] The kitchen room also contains the dining room. Between the family apartment and kitchen, there can be an adjoining room where heirlooms like jars and brasswares are displayed. Behind the kitchen may be the bathroom and toilets. Further to this can be built another open-back end veranda called pelaboh. A louvre is made in the roof to allow sunlight to permeate into the living and kitchen areas. A window opening is made between kitchens to allow exchange or sharing of food.

- The corridor itself is divided into three parts. The space in front of the door, the tempuan, belongs to each bilik unit and is used privately but the dwellers will walk along this path as well. This is where rice can be pounded or other domestic work can be done. A public corridor, a ruai, runs the length of the building in this open space. The ruai, is used by people in the longhouse to get together, and sometimes to make handicrafts like mats, baskets, and pua kumbu. Along the outer wall is the space where guests can sleep, the pantar. Above the upper ruai, a panggau (hung suite) is built for young bachelors of the respective families to live and sleep. For maidens, a meligai is built over the upper main room, hung from the roof structure which is used for secluding maidens if the parents decide to do so, especially by the few aristocratic families. On this side a large veranda, a tanju, is built in front of the building where the rice (padi) is dried and other outdoor activities can take place. The sadau, a sort of attic, runs along under the peak of the roof and serves as storage of paddy and other family possessions. Sometimes the sadau has a sort of gallery from which the life in the ruai can be observed. The pigs and chicken live underneath the house between the stilts.[43]

A basic design of the inner side of each family house consists of an open room (bilek), a covered gallery (ruai), an open verandah (tanju) and a loft (sadau). The covered gallery has three areas called tempuan (highway), the lower ruai and the upper sitting area (pantal) after which is the open verandah. An upper palace (meligai) is built dedicated for children especially if they are raised as princess or prince (anak umbong) with servants to attend to them and thus protected from encounters with unsolicited suitors especially for the maidens in view of the "ngayap" (literally dating) culture. An opening between family rooms is normally provided to allow direct communication and easy sharing between families. The backside of a longhouse can also have a smaller open verandah called 'pelaboh' built. Due to its design, the longhouse is fit for residency, accommodation and a place of worship.

The front side of each longhouse shall be constructed towards the sunrise (east) and hence its backside is on the sunset. This provides enough sunlight for drying activities at the open verandah and to the inner side of the longhouse. The Iban normally design a window on the roof of each family room which is to be opened during daylight to allow sunlight coming in and thus provides sunlight into the inner side of the family room.

Another key factor in determining the right location for building a longhouse is the source of water, either from a river or a natural source of water (mata ai) if it is located on a hill or mount. The access to the sunrise is the overriding factor over the easy access to the river bank. The most ideal orientation of a longhouse is thus facing the sunrise and the river bank.

One more aspect considered when arranging the families in a row along the longhouse is that senior families will be arranged in descending order from the main central post. However, the families on the right hand side will be more senior than the families on the left-hand side. This is to follow the arrangement of the family arrangement in the Sengalang Burong's longhouse where Ketupong's room is situated on the right-hand side while Bejampong's room is on the left-hand side.

A longhouse will be abandoned once it is too far to reach the paddy farms of its inhabitants such as once the walk takes more than half a day to reach the farm. Each family must lighten and use their kitchen twice a month based on the rule not to leave the kitchen cold for an extended period of time, failing which they will be fined which is to be avoided at almost any cost. The inhabitants will then move to nearer to their farms. Normally, the Iban will continue to locate their farms upriver to open new virgin forests that are fertile and thus ensure a good yield. At the same time, the purpose is to have a lot of games from virgin forests, which is a source of protein to supplement the carbohydrate from the rice or wild sago. Nowadays, however, most longhouses are permanently constructed using modern materials like terraced houses in town areas. There are no more new areas to migrate to, anyway. So, the Iban dwell at one place almost permanently unless a new longhouse is being built to replace the old one.

Land ownership

Traditionally, Iban agriculture was based on actual integrated indigenous farming system. Iban Dayaks tend to plant paddy on hill slopes. Agricultural Land in this sense was used and defined primarily in terms of hill rice farming, ladang (garden), and hutan (forest). According to Prof Derek Freeman in his Report on Iban Agriculture, Iban Dayaks used to practice twenty-seven stages of hill rice farming once a year and their shifting cultivation practices allow the forest to regenerate itself rather than to damage the forest, thereby to ensure the continuity and sustainability of forest use and/or survival of the Iban community itself.[44][45] The Iban Dayaks love virgin forests for their dependency on forests but that is for migration, territorial expansion, and/or fleeing enemies.

Once the Iban migrated into a riverine area, they will divide the area into three basic areas i.e. farming area, territorial domain (pemakai menoa) and forest reserve (pulau galau). The farming area is distributed accordingly to each family based on consensus. The chief and elders are responsible to settle any disputes and claims amicably. The territorial domain is a common area where the families of each longhouse are allowed to source for foods and confined themselves without encroachment into domains of other longhouses. The forest reserve is for common use, as a source of natural materials for building longhouse (ramu), boat making, plaiting, etc.

The whole riverine region can consist of many longhouses and thus the entire region belongs to all of them and they shall defend it against encroachment and attack by outsiders. Those longhouses sharing and living in the same riverine region call themselves shared owners (sepemakai).

Each track of virgin forest cleared by each family (rimba) will automatically belong to that family and inherited by its descendants as heirloom (pesaka) unless they migrate to other regions and relinquish their ownership of their land, which is symbolized by a token payment using a simple item in exchange for the land.

Piracy

The Sea Dayaks, as their name implies, are a maritime set of tribes, and fight chiefly in canoes and boats. One of their favorite tactics is to conceal some of their larger boats, and then to send some small and badly manned canoes forward to attack the enemy to lure them. The canoes then retreat, followed by the enemy, and as soon as they pass the spot where the larger boats are hidden, they are attacked by them in the rear, while the smaller canoes, which have acted as decoys, turn and join in the fight. The rivers arc are chosen for this kind of attack, the overhanging branches of trees and the dense foliage of the bank affording excellent hiding places for the boats.[46]

Many of the sea dayaks were also pirates. In the 19th century there was a great deal of piracy, and it was secretly encouraged by the native rulers, who obtained a share of the spoil, and also by the Malays who knew well how to handle a boat. The Malay fleet consisted of a large number of long war boats or prahu, each about 90 feet (27 m) long or more, and carrying a brass gun in the bow, the pirates being armed with swords, spears and muskets. Each boat was paddled by from 60 to 80 men. These boats skulked about in the sheltered coves waiting for their prey, and attacked merchant vessels making the passage between China and Singapore. The Malay pirates and their Dayak allies would wreck and destroy every trading vessel they came across, murder most of the crew who offered any resistance, and the rest were made as slaves. The Dayak would cut off the heads of those who were slain, smoke them over the fire to dry them, and then take them home to treasure as valued possessions.[47]

Military

A Dayak war party in proas and canoes fought a battle with Murray Maxwell following the wreck of HMS Alceste in 1817 at the Gaspar Strait.[48]

The Iban Dayak's first direct encounter with the Brooke and his men was in 1843, during the attack by Brooke's forces on the Batang Saribas region i.e. Padeh, Paku, and Rimbas respectively. The finale of this battle was the conference at Nagna Sebuloh to sign a peace Saribas treaty to end piracy and headhunting but the natives refused to sign it, rendering the treaty moot.[49]

In 1844, Brooke's force attacked Batang Lupar, Batang Undop, and Batang Skrang to defeat the Malay sharifs and Dayak living in these regions. The Malay sharifs were easily defeated at Patusin in Batang Lupar, without a major fight despite their famous reputation and power over the native inlanders. However, during the battle of Batang Undop, one of Brooke's men, British Navy officer Mr. Charles Wade was killed in action at the battle of Ulu Undop while chasing the Malay sheriffs upriver. Subsequently, Brooke's Malay force headed by Datu Patinggi Ali and Mr. Steward was totally defeated by the Skrang Iban force at the battle of Kerangan Peris in the Batang Skrang region.[50]

In 1849, at the Battle of Beting Maru, a convoy of Dayak boats that were returning from a sojourn at the River Rajan spotted Brooke's man of war, the Nemesis. They then landed on the Beting Maru sandbar and retreated to their villages, with two Dayak boats acting as a diversion by sailing towards the Nemesis and engaging her, with the two boats managing to retreat safely after a few shots were exchanged. The next day, the Dayak ambushed Brooke's pursuing force, killing two of Brooke's Iban entourage before pulling back.[51]

Layang, the son-in-law of Libau "Rentap" was known as the first Iban slayer of a white man in the person of Mr. Alan Lee "Ti Mati Rugi" (died in vain) at the Battle of Lintang Batang in 1853, above the Skrang fort built by Brooke in 1850. The Brooke government had to launch three successive punitive expeditions against Libau Rentap to conquer his fortress known as Sadok Mount. In total, the Brooke government conducted 52 punitive expeditions against the Iban including one against the Kayan.[52]

The Iban attacked the Japanese force stationed at the Kapit fort at the end of the Second World War in 1945. The Sarawak Rangers which were mostly Dayak participated in the anti-communist insurgency during the Malayan Emergency between 1948 and 1960.[53] The Sarawak Rangers were despatched by the British to fight during the Brunei Rebellion in 1962.[54] Later, the Sarawak Rangers fought against the Indonesian forces during the Confrontation against the formation of the Federation of Malaysia along the border with Kalimantan in 1963.

Two highly decorated Iban Dayak soldiers from Sarawak in Malaysia are Temenggung Datuk Kanang anak Langkau and Sgt Ngaliguh (both awarded Seri Pahlawan Gagah Perkasa) and Awang anak Raweng of Skrang (awarded a George Cross).[55][56] So far, only one Dayak has reached the rank of a general in the Malaysian military: Brigadier-General Stephen Mundaw in the Malaysian Army, who was promoted on 1 November 2010.[57]

Malaysia's most decorated war hero is Kanang anak Langkau due to his military services helping to liberate Malaya (and later Malaysia) from the communists. The youngest of the PGB holder is ASP Wilfred Gomez of the Police Force.[58]

There were six holders of Sri Pahlawan (SP) Gagah Perkasa (the Gallantry Award) from Sarawak, and with the death of Kanang Anak Langkau, there is one SP holder in the person of Sgt. Ngalinuh.[59]

Attire

The ceremonial mandaus used for dances are as beautifully adorned with feathers, as are the costumes. There are various terms to describe different types of Dayak blades. The Nyabor is the traditional Iban Scimitar, Parang Ilang is common to Kayan and Kenyah Swordsmiths, pedang is a sword with a metallic handle and Duku is a multipurpose farm tool and machete of sorts.

Normally, the sword is accompanied by a wooden shield called a terabai which is decorated with a demon face to scare off the enemy. Other weapons are sangkoh (spear) and sumpit (blowpipe) with lethal poison at the tip of its laja. To protect the upper body during combat, a gagong (armour) which is made of animal hard skin such as leopards is worn over the shoulders via a hole made for the head to enter.[60]

Dayaks normally build their longhouses on high posts on high ground where possible for protection. They also may build kuta (fencing) and kubau (fort) where necessary to defend against enemy attacks. Dayaks also possess some brass and cast iron weaponry such as brass cannon (bedil) and iron cast cannon meriam. Furthermore, Dayaks are experienced in setting up animal traps (peti) which can be used for attacking the enemy as well. The agility and stamina of Dayaks in jungles give them advantages. However, at the end, Dayaks were defeated by handguns and disunity among themselves against the colonialists.

Most importantly, Dayaks will seek divine helps to grant them protection in the forms of good dreams or curses by spirits, charms such as pengaroh (normally poisonous), empelias (weapon straying away) and engkerabun (hidden from normal human eyes), animal omens, bird omens, good divination in the pig liver or by purposely seeking supernatural powers via nampok or betapa or menuntut ilmu (learning knowledge) especially kebal (weapon-proof).[61] During headhunting days, those going to farms will be protected by warriors themselves, and big agriculture is also carried out via labour exchange called bedurok (which means a large number of people working together) until completion of the agricultural activity. Kalingai or pantang (tattoo) is made unto bodies to protect from dangers and other signifying purposes such as travelling to certain places.[62]

The traditional Iban Dayak male attire consists of a sirat (loincloth) attached with a small mat for sitting), lelanjang (headgear with colourful bird feathers) or a turban (a long piece of cloth wrapped around the head), marik (chain) around the neck, engkerimok (ring on thigh) and simpai (ring on the upper arms).[63] The Iban Dayak female traditional attire comprises a short "kain tenun betating" (a woven cloth attached with coins and bells at the bottom end), a rattan or brass ring corset, selampai (long scarf) or marik empang (beaded top cover), sugu tinggi (high comb made of silver), simpai (bracelets on upper arms), tumpa (bracelets on lower arms) and buah pauh (fruits on hand).[64]

The Dayaks especially the Ibans appreciate and treasure very much the value of pua kumbu (woven or tied cloth) made by women while ceramic jars which they call tajau obtained by men. Pua kumbu has various motives for which some are considered sacred.[65] Tajau has various types with respective monetary values. The jar is a sign of good fortune and wealth. It can also be used to pay fines if some adat is broken in lieu of money which is hard to have in the old days. Beside the jar being used to contain rice or water, it is also used in ritual ceremonies or festivals and given as baya (provision) to the dead.[66]

The adat tebalu (widow or widower fee) for deceased women for Iban Dayaks will be paid according to her social standing and weaving skills and for the men according to his achievements in his lifetime.[67][68]

Dayaks being accustomed to living in jungles and hard terrains, and knowing the plants and animals are extremely good at following animals trails while hunting and of course tracking humans or enemies, thus some Dayaks became very good trackers in jungles in the military e.g. some Iban Dayaks were engaged as trackers during the anti-confrontation by Indonesia against the formation of Federation of Malaysia and anti-communism in Malaysia itself. No doubt, these survival skills are obtained while doing activities in the jungles, which are then utilised for headhunting in the old days.

Agriculture and economy

Traditionally, Iban agriculture was based on actual integrated indigenous farming system. Ibans plant hill rice paddies once a year in twenty-seven stages as described by Freeman in his report on Iban Agriculture. Agricultural Land in this sense was used and defined primarily in terms of hill rice farming, ladang (garden), and hutan (forest).[69][70] The main stages of the paddy cultivation is followed by the Iban lemambang bards to compose their ritual incantations. The bards also analogizes the headhunting expedition with the paddy cultivation stages. Other crops planted include ensabi, cucumber (rampu amat and rampu betu), brinjal, corn, lingkau, millet and cotton (tayak). Downriver Iban plant wet rice paddy at the low-lying riverine areas which are beyond the reach of the salt water tide.[71]

Dayaks organised their labour in terms of traditionally based landholding groups which determined who owned rights to land and how it was to be used. The Iban Dayaks practice a rotational and reciprocal labour exchange called bedurok to complete works on their farms own by all families within each longhouse. The "green revolution" in the 1950s, spurred on the planting of new varieties of wetland rice amongst Dayak tribes.

For cash, the Ibans find jungle produce to sell at the market or town. Later, they planted rubber, pepper and cocoa. Nowadays, many Ibans work in towns to seek better sources of income.[72]

Trading is not a natural activity for the Iban. They did trade paddy for jars or salted fish coming from the sea in the old days but paddy lost its economic value a long time ago. Not much yield can be produced from repetitively replanted areas anyway because their planting relies on the natural source of fertilizer from the forest itself and the source of water for irrigation is from the rain, hence the cycle of the weather season is important and need to be correctly followed. Trading of sundries, jungle produce or agricultural produce is normally performed by the Chinese who commuted between the town and the location of the shop.[73]

Military

The Iban are famous for being fearsome warriors in the past in defence of homeland or for migration to virgin territories. Two highly decorated Iban Dayak soldiers from Sarawak in Malaysia are Temenggung Datuk and Kanang anak Langkau (awarded the Seri Pahlawan Gagah Perkasa or Grand Knight of Valour)[74] and Awang anak Raweng of Skrang (awarded a George Cross).[75][76] So far, only one Dayak has reached the rank of general in the military, Brigadier-General Stephen Mundaw in the Malaysian Army, who was promoted on 1 November 2010.[77]

Malaysia's most decorated war hero is Kanang Anak Langkau for his military service helping to liberate Malaya (and later Malaysia) from the communists, being the only soldier awarded both Seri Pahlawan (The Star of the Commander of Valour) and Panglima Gagah Berani (The Star of Valour). Among all the heroes are 21 holders of the Panglima Gagah Berani (PGB) including 2 recipients of the Seri Pahlawan. Of this total, there are 14 Ibans, two Chinese army officers, one Bidayuh, one Kayan and one Malay. But the majority of the Armed Forces are Malays, according to a book – Crimson Tide over Borneo. The youngest of the PGB holders is ASP Wilfred Gomez of the police force.[78]

There were six holders of Sri Pahlawan (SP) and Panglima Gagah Perkasa from Sarawak, and with the death of Kanang Anak Langkau, there is one SP holder in the person of Sgt. Ngalinuh (an Orang Ulu).

In popular culture

- The episode "Into the Jungle" from Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations included the appearance of Itam, a former Sarawak Ranger and one of the Iban people's last members with the entegulun (Iban traditional hand tattoos) signifying his taking of an enemy's head.

- The film The Sleeping Dictionary features Selima (Jessica Alba), an Anglo-Iban girl who falls in love with John Truscott (Hugh Dancy). The movie was filmed primarily in Sarawak, Malaysia.

- Malaysian singer Noraniza Idris recorded "Ngajat Tampi" in 2000 and followed by "Tandang Bermadah" in 2002, which are based on traditional Iban music compositions. Both songs became popular in Malaysia and neighbouring countries.

- Chinta Gadis Rimba (or Love of a Forest Maiden), a 1958 film directed by L. Krishnan based on the novel of the same name by Harun Aminurrashid, tells about an Iban girl, Bintang, who goes against the wishes of her parents and runs off to her Malay lover. The film is the first time a full-length feature film was shot in Sarawak and the first time an Iban woman played the lead character.[79]

- Bejalai is a 1987 film directed by Stephen Teo, notable for being the first film to be made in the Iban language and also the first Malaysian film to be selected for the Berlin International Film Festival. The film is an experimental feature about the custom among the Iban young men to do a "bejalai" (go on a journey) before attaining maturity.[80]

- In Farewell to the King, a 1969 novel by Pierre Schoendoerffer plus its subsequent 1989 film adaptation, American prisoner-of-war Learoyd escapes a Japanese firing squad by hiding in the wilds of Borneo, where he is adopted by an Iban community.

- In 2007, Malaysian company Maybank produced a wholly Iban-language commercial commemorating Malaysia's 50th anniversary of independence. The advert, directed by Yasmin Ahmad with help of the Leo Burnett agency, was shot in Bau and Kapit and used an all-Sarawakian cast.[81]

- A conflict between a proa of "sea-dyaks" and the shipwrecked Jack Aubrey and his crew forms much of the first part of The Nutmeg of Consolation (1991), Patrick O'Brian's fourteenth Aubrey-Maturin novel.

Notable people

- Bandi Anak Ragai, or well known as Apai Janggut, chief of Sungai Utik Iban longhouse and 2019 UN Equator Prize awardee.

- Rentap, Leader of a rebellion against the Brooke administration and used the title of Raja Ulu (king of the Interior).

- Datu Bandar Bawen, Bruneian political figure, a close friend to Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin.

- Temenggung Koh Anak Jubang, the first paramount chief of Dayak in Sarawak.

- Jugah anak Barieng, second Paramount Chief of the Dayak people and the key signatory on behalf of Sarawak to the Malaysia Agreement.

- Datu Tigai anak Bawen, (1946–2005), business tycoon and millionaire. Cousin of Jugah anak Barieng.

- Stephen Kalong Ningkan, the first Chief Minister of Sarawak.

- Tawi Sli, the second Chief Minister of Sarawak.

- Kanang anak Langkau, National hero of Malaysia. Awarded the medal of valour "Sri Pahlawan Gagah Berani" by the Malaysian Government.

- Awang Anak Raweng awarded the George Cross medal by the British Government.

- Henry Golding, actor; has an English father and Iban mother.

- Daniel Tajem Miri, former Deputy Chief Minister of Sarawak.

- Misha Minut Panggau, First International Award Winning Iban Lady Feature Film Director, Producer & Script Writer (Belaban Hidup-Infeksi Zombie).

- Cassidy Panggau, Iban Feature Film Actor.

- Ray Lee, Award Winning Film Director, Producer, Music Entrepreneur & Creative Activist.

- Haimie Anak Nyaring , Brunei Footballer player.

- Suhaimi Anak Sulau , Brunei Football player.

- Francisca Luhong James , Miss Universe Malaysia 2020; has an Orang Ulu father and Iban mother.

- Micheal Anak Garing, a Sarawakian murderer who was executed in Singapore

- Tony Anak Imba, a Sarawakian murderer sentenced to life imprisonment and caning by Singapore.

- Kho Jabing, a Sarawakian of mixed Chinese and Iban descent who was executed in Singapore for murder

See also

Citations

- "Launching of Report On The Key Findings Population and Housing Census of Malaysia 2020" (PDF). Department of Statistics Malaysia. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- "Iban of Brunei". People Groups. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- "Borneo trip planner: top five places to visit". News.com.au. 21 July 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Sutrisno, Leo (26 December 2015). "Rumah Betang". Pontianak Post. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Osup, Chemaline Anak (2006). "Puisi Rakyat Iban – Satu Analisis: Bentuk Dan Fungsi" [Iban Folk Poetry – An Analysis: Form and Function] (PDF). University of Science, Malaysia (in Indonesian).

- "Use of Papan Turai by Iban". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 29 May 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Mawar, Gregory Nyanggau (21 June 2006). "Gawai". Iban Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Early Iban Migration – Part 1". 26 March 2007.

- Simonson, T. S.; Xing, J.; Barrett, R.; Jerah, E.; Loa, P.; Zhang, Y.; Watkins, W. S.; Witherspoon, D. J.; Huff, C. D.; Woodward, S.; Mowry, B.; Jorde, L. B. (8 April 2023). "Ancestry of the Iban Is Predominantly Southeast Asian: Genetic Evidence from Autosomal, Mitochondrial, and Y Chromosomes". PLOS ONE. 6 (1): e16338. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016338. PMC 3031551. PMID 21305013.

- "Ngepan Batang Ai (Iban Women Traditional Attire)" (PDF). 8 April 2023.

- "Iban as a koine language in Sarawak". 1 May 2023.

- "Iban as a koine language in Sarawak". 1 May 2023.

- "Iban as a koine language in Sarawak". 1 May 2023.

- "Iban as a koine language in Sarawak". 1 May 2023.

- "Asal usul Melayu Sarawak: Menjejaki titik tak pasti". 1 May 2023.

- "Iban Migration – Peturun Iban". Iban Cultural Heritage. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "The Orang Kaya Pemancha Dana "Bayang" of Padeh". Ibanology. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Iban Heroes". Iban Customs & Traditions. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "The Rajahs of Sarawak". The Spectator. 29 January 1910.

- "Sir James Brooke's personal narrative of the insurrection at Sarawak". The Sydney Morning Herald. 31 July 1857. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Heidhues, MFS (2003). Golddiggers, farmers, and traders in the "Chinese Districts" of West Kalimantan, Indonesia. SEAP Ithaca, New York. p. 102.

- http://pariwisata.kalbar.go.id/index.php?op=deskripsi&u1=1&u2=1&idkt=4

- Heimannov, Judith M. (9 November 2007). "'Guests' can succeed where occupiers fail". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Wen-Qing, Ngoei (2019). Arc of Containment: Britain, the United States, and Anticommunism in Southeast Asia. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1501716409.

- "This is the War in Malaya". The Daily Worker. 28 April 1952.

- Peng, Chin; Ward, Ian; Miraflor, Norma (2003). Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History. Singapore: Media Masters. pp. 302–303. ISBN 981-04-8693-6.

- "Iban as a koine language in Sarawak". 1 May 2023.

- "The Iban of Temburong: Migration, Adaptation and Identity in Brunei Darussalam" (PDF). 3 June 2023.

- The Austronesians: historical and comparative perspectives. Peter Bellwood, James J. Fox, Darrell Tryon. ANU E Press, 2006. ISBN 1-920942-85-8, ISBN 978-1-920942-85-4

- "Part 1: Iban Adat Law and Custom". Iban Cultural Heritage. 22 April 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Origin of Adat Iban: Part 3". Iban Cultural Heritage. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "2010 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia" (PDF) (in Malay and English). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2012. checked: yes. p. 108.

- "Population by Religion, Sex and Census Year".

- Tassim, Fatimah Az-Zahra. "Why is the Iban tribe excluded from the official 'tujuh puak Brunei' (seven tribes of Brunei) and what is their experience being born and raised in Bruneian society?".

- Sutlive, Vinson; Sutlive, Joanne, eds. (2001). The Encyclopaedia of Iban Studies: Iban History, Society, and Culture. Vol. 2: H-N. Kuching: The Tun Jugah Foundation. p. 697. ISBN 978-9-83405-130-3.

- Matusky, Patricia (1985). "An Introduction to the Major Instruments and Forms of Traditional Malay Music". Asian Music. 16 (2): 121–182. doi:10.2307/833774. JSTOR 833774.

- Mercurio, Philip Dominguez (2006). "Traditional Music of the Southern Philippines". PnoyAndTheCity: A center for Kulintang – A home for Pasikings. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- "Pua Kumbu – The Legends Of Weaving". Ibanology. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- "Pua Kumbu – The Legends Of Weaving". 8 April 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Restoring Panggau Libau: a reassessment of engkeramba' in Saribas Iban ritual textiles (pua' kumbu')". 23 April 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- See examples here https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.269499373193118.1073741835.101631109979946&type=3,

- "Ekspresi Cinta dan Kehidupan Orang Dayak Iban". Kompas.

- Paula, Harris; Bellingham, Katy; J Fox, James (September 2006). Inside Austronesian Houses: Perspectives on Domestic Designs for Living – Chapter 4. Posts, Hearths and Thresholds: The Iban Longhouse as a Ritual Structure Prev – Sources and Elders. Australia: Australian National University. pp. 70–71. ISBN 1-920942-84-X. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- J. D. Freeman, Report on the Iban.

- J. D. Freeman, Iban Agriculture.

- Wood, J. G (1878). The uncivilized races of men in all countries of the world: being a comprehensive account of their manners and customs, and of their physical, social, mental, moral and religious characteristics volume 2. J.B. Burr and Co. p. 1136. OCLC 681697209.

- Gomes, Edwin Herbert (1912). Children of Borneo. Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier. p. 12. OCLC 262467039.

- No. XV. Sir Murray Maxwell, Knight". The Annual Biography and Obituary. XVI: 220–255. 1832. Retrieved on 25 July 2008. Annual Biography and Obituary, 1832 Vol. XVI, p. 239

- Spencer St John: The Life of Sir James Brooke. Chapter IV, p. 51. 1843–1844. Available at https://archive.org/stream/lifesirjamesbro01johngoog/lifesirjamesbro01johngoog_djvu.txt

- Captain Henry Keppel: The Expedition to Borneo of HMS Dido, p.110. Available at https://archive.org/stream/expeditiontobor00kellgoog/expeditiontobor00kellgoog_djvu.txt

- Spencer St John: The Life of Sir James Brooke, The Battle of Beting Marau, Chapter IX, p.174, 1849. Available at https://archive.org/stream/lifesirjamesbro01johngoog/lifesirjamesbro01johngoog_djvu.txt

- Charles Brooke: Tens Year in Sarawak, Chapter I, p. 37. Available at http://www.archive.org/stream/tenyearsinsarwa03broogoog/tenyearsinsarwa03broogoog_djvu.txt

- A. J. Stockwell; University of London. Institute of Commonwealth Studies (2004). Malaysia. The Stationery Office. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-11-290581-3.

- Abdul Majid, Harun (2007). Rebellion In Brunei – The 1962 Revolt, Imperialism, Confrontation and Oil (PDF). London, New York: I.B.Tauris. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-84511-423-7.

- "Iban Trackers". Ibanology. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Iban Heroes Part 2". Iban Customs & Traditions. 21 January 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Stephen Mundaw Becomes First Iban Brigadier General". Borneo Post Online. 2 November 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- The Borneo Post (2013): PGB recipient Gomez dies battling cancer. Retrieved at https://www.theborneopost.com/2013/02/03/pgb-recipient-gomez-dies-battling-cancer/ (Accessed on 18/01/2020.

- New Sarawak Tribune (2018): Two Sarawak 'Bravehearts' who took on an Army of 100 CTs. Retrieved at https://www.newsarawaktribune.com.my/two-sarawak-bravehearts-who-took-on-an-army-of-100-cts/. Accessed on 18/01/2020.

- "Gagong perengka ke beguna ba bansa Iban". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 12 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Pengaroh dalam budaya Iban". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 29 May 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Welcome". Borneoheadhunter. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Iban Traditional Clothing and Attire". Iban Customs & Traditions. 7 June 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- http://www.miricommunity.net/viewtopic.php?f=13&t=35112

- Kedit, Vernon (2009). "Restoring Panggau Libau: A Reassessment of Engkeramba' in Saribas Iban Ritual Textiles (Pua' Kumbu')". Borneo Research Bulletin. 40: 221–248 – via Free Online Library.

- "Types of Tajau". Ibanology. 30 May 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Iban Customary Law for Tebalu (Widow and Widower)". Ibanology. 1 March 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Kayau Indu and Iban women social status (Ranking)". Ibanology. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Freeman, Derek (1955). Iban agriculture; a report on the shifting cultivation of hill rice by the Iban of Sarawak. H.M. Stationery Off. OCLC 2392813.

- Freeman, Derek (1955). Report on the Iban of Sarawak. G.P.O. OCLC 2417681.

- Malcolm Cairns, ed. (2017). Shifting Cultivation Policies: Balancing Environmental and Social Sustainability. CABI. p. 213. ISBN 978-17-863-9179-7.

- Jayum A. Jawan (1994). Iban Politics and Economic Development: Their Patterns and Change. Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. p. 41. ISBN 96-794-2284-4.

- Tagliacozzo, Eric; Chang, Wen-Chin, eds. (8 April 2011). Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia. Duke University Press. p. 11. doi:10.1215/9780822393573. hdl:20.500.12657/25791. ISBN 978-0-8223-9357-3.

- Ma Chee Seng & Daryll Law (6 August 2015). "Remembering Fallen Heroes on Hero Memorial Day". New Sarawak Tribune. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- Rintos Mail & Johnson K Saai (6 September 2015). "Ailing war hero may miss royal audience this year". The Borneo Post. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- "Sarawak (Malaysian) Rangers, Iban Trackers and Border Scouts". Winged Soldiers. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- "Stephen Mundaw becomes first Iban Brigadier General". The Borneo Post. 2 November 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- "PGB recipient Gomez dies battling cancer". The Borneo Post. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- "Wanted: a jungle belle who knows about love". The Straits Times. 3 September 1956. p. 7. Retrieved 28 March 2017 – via NewspaperSG.

- "Bejalai (1989)". IMDb. 25 March 1990. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- coconutice (4 September 2007), Maybank Advert in Iban, retrieved 27 March 2017

General bibliography

- Sir Steven Runciman, The White Rajahs: a history of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946 (1960).

- James Ritchie, The Life Story of Temenggong Koh (1999)

- Benedict Sandin, Gawai Burong: The chants and celebrations of the Iban Bird Festival (1977)

- Greg Verso, Blackboard in Borneo, (1989)

- Renang Anak Ansali, New Generation of Iban, (2000)

External links

Media related to Iban people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Iban people at Wikimedia Commons