Dusun people

Dusun is the collective name of an indigenous ethnic group to the Malaysian state of Sabah of North Borneo. Collectively, they form the largest ethnic group in Sabah. The Dusun people have been internationally recognised as indigenous to Borneo since 2004 as per the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).[1]

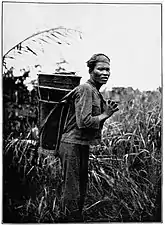

Dusun Tindal of Kota Belud | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 1,100,283 | |

| Languages | |

| Dusun, Sabah Malay and English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Majority), Islam, Momolianism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Orang Sungai, Ida'an, Bisaya, Murut, Idaanic people, Lun Bawang/Lundayeh other Austronesian peoples | |

Other similarly named, yet unrelated groups can also be found in Brunei and the Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Bruneian Dusuns (Sang Jati Dusun) are directly related to the Dusun people of Sabah, both belong to the same Dusunic Family group. Bruneian Dusuns share a common origin, language and identity with the Bisaya people of Brunei, northern Sarawak and southwestern Sabah. In Indonesia, the Barito Dusun groups that can be found throughout the Barito River system belonged to the Ot Danum Dayak people instead.

Etymology

The Dusuns do not have the word 'Dusun' in their vocabulary.[2] It has been suggested that the term 'Dusun' was a term used by the Sultan of Brunei to refer to the ethnic groups of inland farmers in present-day Sabah.[2] 'Dusun' means 'orchard' in Malay. Since most of the west coast of North Borneo was under the influence of the Sultan of Brunei, taxes called 'Duis' (also referred to as the 'River Tax' in the area southeast of North Borneo) were collected by the sultanate from the 'Orang Dusun', or 'Dusun people'. Hence, since 1881, after the establishment of the British North Borneo Company, the British administration categorised the linguistically-similar, 12 main and 33 sub-tribes collectively as 'Dusun'.[2] The Buludupih and Idahan, who had converted to Islam, had preferred to be called "Sungei" and "Idaan" respectively although they come from the same sub-tribes.[3]

Genetic Studies

According to a Genome-wide SNP genotypic data studies by human genetics research team from University Malaysia Sabah (2018),[4] the Northern Borneon Dusun (Sonsogon, Rungus, Lingkabau and Murut) are closely related to Taiwan natives (Ami, Atayal) and non–Austro-Melanesian Filipinos (Visayan, Tagalog, Ilocano, Minanubu), rather than populations from other parts of Borneo.

Introduction

The Dusun ethnic group at one time made up almost 40% of the population of Sabah and is broken down into more than 30 sub-ethnic, or dialect groups, or tribes, each speaking a slightly different dialect of the Dusunic and Paitanic family language. They are mostly mutually understandable. The name 'Dusun' was popularised by the British colonial masters who borrowed the term from the Brunei Malays.

Most Dusuns have converted to mainstream religions such as Christianity (both Roman Catholic and Protestant) and Sunni Islam, although animism is still being practised by a minority of Dusun.

The Dusun of old traded with the coastal people by bringing their agricultural and forest produce (such as rice and amber 'damar') to exchange for salt, salted fish and other products. The Dusun has a special term to describe this type of trading activity, i.e. mongimbadi. This was before the development of the railroad and road network connecting the interior with the coastal regions of Sabah. The present Tambunan-Penampang road was largely constructed based on the trading route used by the Bundu-Liwan Dusun to cross the Crocker Range on their mongimbadi.

The vast majority of Dusuns live in the hills and upland valleys and have a reputation for peacefulness, hospitality, hard work, frugality, drinking and aversion to violence. They are now modernised and well-integrated into the larger framework of Malaysian society, taking up various occupations as government servants and employees in the private sector, as well as becoming business owners. Many have completed tertiary education both locally and overseas (in America, England, Australia, and New Zealand).

In their old traditional setting, they use various methods of fishing, including using the juice called "tuba" derived from the roots of the "surinit" plant to momentarily stun fish in rivers.

The arrival of Christian Missionaries in the 1880s brought to the Dayaks and the Dusuns of Borneo the ability to read, write and converse in English. This opened their minds and stimulated them to get involved in community development. The tribes who were first exposed to this modernisation were the Tangaa or Tangara who dwelt in the Papar and Penampang coastal plains and who were responsible for the spread of nationalist sentiments to the other tribes.

The first attempt to translate the Bible was in Tangaa Dusun, also referred to as the "z" dialect. This was followed by a Tangaa Dusun Dictionary. The first registered Native friendly Society was the Kadazan Society and the political party «»registered in North Borneo was the United National Kadazan Organization under the leadership of Donald Stevens, who was made the first Huguan Siou of the Dusun aka Kadazan Nation of 12 main and 33 sub-tribes. When Sabah became independent on 31 August 1963, Donald Stevens became the Prime/Chief Minister, a position he continued to hold after Sabah joined Malaysia on 16 September 1963.

Culture and society

Harvest Festival

Harvest Festival or Pesta Kaamatan is an annual celebration by the people of Kadazandusun in Sabah. It is a one-month celebration from 1 to 31 May. In modern-day Kaamatan Festival celebrations, 30 and 31 May are the climax for the state-level celebration that happens at the place of the yearly Kaamatan Festival host. Today's Kaamatan celebration is synonymous with a beauty pageant competition known as Unduk Ngadau, a singing competition known as Sugandoi, Tamu, non-halal food and beverages stalls, and handicraft arts and cultural performances in traditional houses.[5]

During the old days, Kaamatan was celebrated to give thanks to ancient Gods and rice spirits for the bountiful harvesting to ensure continuous paddy yield for the next paddy plantation season. Nowadays, the majority of the Kadazan-dusun people have embraced Christianity and Islam. Although the Kaamatan is still celebrated as an annual tradition, it is no longer celebrated for the purpose of meeting the demands of the ancestral spiritual traditions and customs, but rather in honouring the customs and traditions of the ancestors. Today, Kaamatan is more symbolic as a reunion time with family and loved ones. Domestically, modern Kaamatan is celebrated as per individual personal aspiration with the option of whether or not to serve the Kadazandusun traditional food and drinks which are mostly non-halal.[6]

Traditional foods and drinks

A few of the most well known traditional foods of the Kadazandusun people are hinava, noonsom, pinaasakan, bosou, tuhau, kinoring pork soup (meat of a wild boar usually referred to by the locals as sinalau bakas) and rice wine chicken soup. Some of the well-known traditional drinks of Kadazandusun are tapai, tumpung or segantang, lihing, montoku and bahar.[7]

Traditional costumes

The traditional costume of the Kadazandusun is generally called the "Koubasanan costume", made out of black velvet fabric with various decorations using beads, flowers, coloured buttons, golden laces, linen, and unique embroidery designs.[8] The traditional costume that is commonly commercialised as the cultural icon of the Kadazandusun people is the Koubasanan costume from the Penampang district. The koubasanan costume from the Penampang district consists of 'Sinuangga' worn by women and 'Gaung' for men. 'Sinuangga' comes with a waistband called 'Himpogot' (made out of connected silver coins, also known as the money belt), 'Tangkong' (made out of copper loops or rings fastened by strings or threads), 'Gaung' (decorated with gold lace and silver buttons) and a hat that is called 'Siga' (made out of weaved dastar fabric). The decorations and designs of the koubasanan costume are usually varied by region.[8] For example, the koubasanan dress design for Kadazandusun women of Penampang usually comes in a set of sleeveless blouse combined with long skirts and no hats, while the koubasanan dress design for Kadazandusun women of Papar comes in a set of long sleeves blouse combined with knee-length skirts and wore with a siung hat. There are over 40 different designs of the Koubasanan costume across Sabah that belong to different tribes of the Kadazandusun community.[7]

.jpg.webp)

Traditional dance

Sumazau dance is the traditional dance of Kadazandusun. Usually, the sumazau dance is performed by a pair of men and women dancers wearing traditional costumes. Sumazau dance is usually accompanied by the beats and rhythms of seven to eight gongs. The opening movement for sumazau dance is the parallel swinging of the arms back and forth at the sides of the body, while the feet spring and move the body from left to right. Once the opening dance moves are integrated with the gong beats and rhythms, the male dancer will chant "heeeeee!", indicating that it is time to change the dance moves. Upon hearing this chant, dancers will raise their hands to the sides of their body and in line with their chest, and move their wrists and arms up and down resembling the movement of a flying bird. There is plenty of choreography of sumazau dance, but the signature dance move of the sumazau will always be the flying bird arms movement, parallel arms swinging back and forth at the sides of the body, and the springing feet.[7][9]

Traditional music

The Kadazandusun traditional music is usually orchestrated in the form of a band consisting of musicians using traditional musical instruments, such as the bamboo flute, sompoton, togunggak, gong, and kulintangan. Musical instruments in Sabah are classified into chordophones (tongkungon, gambus, sundatang or gagayan), aerophones (suling, turali or tuahi, bungkau, sompoton), ideophones (togunggak, gong, kulintangan), and membranophones (kompang, gendang or tontog). The most common musical instruments in Kadazandusun ceremonies are gong, and kulintangan. The gong beat usually varies by regions and districts, and the gong beat that is often played at the official Kaamatan celebration in KDCA is the gong beat from the Penampang district.[7][9]

Traditional handicrafts

Kadazandusun people use natural materials as resources in producing handicrafts, including bamboo, rattan, lias, calabash, and woods. Some of the many handicrafts that are identified with the Kadazandusun people are wakid, barait, sompoton, pinakol, siung hat, parang and gayang.

Before the mentioned handicrafts were promoted and commercialised to represent the Kadazandusun cultures, they were once tools that were used in daily lives. In fact, some of these handicrafts are still used for their original purpose to this day. Wakid and barait are used to carry harvested crops from farms. Sompoton is a musical instrument. Pinakol is an accessory used in ceremonials and rituals. Parang/machetes and gayang/swords are used as farming and hunting tools, as well as weapons in series of civil wars of the past, which indirectly made the Kadazandusun known as headhunters in the past.[7]

Religion

The mythology is that the Dusun originated from a place called Nunuk Ragang (whose name signifies ‘red-coloured Ficus/banyan tree’).[10][11] This was traditionally believed to be located where the Liwagu and Gelibang rivers met, east of the city of Ranau.[12] The quasi-governmental Kadazandusun Cultural Association claimed that this place was located at a village called Tampias in Ranau, renamed "Nunuk Ragang".[11]

Sub-ethnic groups

Dusun Lotud

The Dusun Lotud occupy the Tuaran district (including Tamparuli sub-district and also Kiulu and Tenghilan villages) as well as the suburb of Telipok in the city of Kota Kinabalu.

From the time before the spread of the major world religions in Southeast Asia and until the present day, the ethnic Lotud were animists.

Bruneians use the word 'Dusun' to identify farmers who have a piece of land planted with fruits or tend orchards. The term was adopted by the British during the period of North Borneo Chartered Company rule from 1881 to 1941.

According to researchers, the Lotud ethnic group was synonymous with the word 'Suang Lotud' and can be found in 35 villages in Tuaran district. The ethnic Dusun Lotud called Lotude were based on the anecdotes not written by their ancestors. The Lotud women were known to wear skirts below the knees only. The word 'otud' in Dusun Lotud dialect means 'Lutut' or knee.

A husband from ethnic Dusun Lotud can practice polygamy and can divorce.

The 'Adat' or Custom of 'Dusun Lotud' marriage processes is divided into 35 segments like Suruhan, (merisik or bilateral meeting), monunui (bertunang or engagement), popiodop ('bermalam' or stay a night atau ditidur or 'sleeping together'), Matod (kahwin or wedding) and mirapou ('adat' or custom).

Before the 1950s, the partners for Dusun Lotud children were chosen by their parents. The male's family will appoint an elderly person known as 'suruhan' qualified on the 'adat resam' and will visit the female's house for the purpose of 'merisik' or negotiating.

The 'Suruhan' is aimed at delivering a message to engage the daughter from the female's family. The girl's family requests for a duration of days before the 'Risikan' or negotiation could be accepted. Many matters have to be clearly made known like the family tree, character, the capability of the male's side, and to evaluate the meaning of a dream that occurred in the female's family. If the female's side had a bad dream, 'sogit mimpi' is done for 'perdamaian' or peace. Based on 'adat', when the males had no 'suruhan' or appointee, they can be fined on 'adat malu' by the girl's family.

Adat Monunui ('bertunang' or engagement) side the proposal of marriage or 'risikan' is accepted by the girl's side, both parties will discuss to fix the date for 'Adat Monunui'. They will find the suitable date and month in the Dusun Lotud calendar like the night of the 14th in a one-month cycle called 'tawang kopiah' or the 15th night called tolokud, to perform 'monunui'.

As a symbol of engagement, the man's side will give a ring to the woman only. 'Adat Monunui' can only be done in the morning before 1 pm. After completion of the ceremony, the man's family members have to leave the woman's home before 4 pm.

In the 'adat monunui', the head of the village and the appointee are the frontline people in the ceremony. Both parties of the families will be represented by the head of the village. At this time the girl proposed to be the fiancée must be in the bedroom or in another place not to be seen by the male's family. The man will not be allowed in the girl's living room before the 'monunui' ends.[13]

The most important elements in 'adat menunui' (engagement) are 'berian/mas kawin' (tinunui), 'belanja dapur' ('wang hangus' or kitchen expenses), 'hantaran tunang' or dowry, 'sogit' atau adat keluarga (jika ada or if family custom exist), tempoh bertunang (duration of engagement).

The list of valuables equivalent to dowry items delivered to the girl are 'karo aman tunggal', 'karo lawid', 'kalro inontilung', 'karo dsapau', 'kemagi lawid', 'kemagi 3 rondog', 'badil' or cannon, 'tajau' or vase, 'canyang tinukul', 'tatarapan', two pieces of 'rantakah', two pieces of 'sigar emas', 'simbong bersiput', 'pertina', 'tompok', gong (tawag-tawag), 'tutup panasatan' ('canyang'), 'kampil', 'kulintangan', two pieces of 'simbong bersiput'.

At the traditional pre-speech, 'adat berian' or dowry custom and belanja dapur or kitchen expenses, the heads of the villages from the man's and girl's sides will start the pre-discussion. They have prepared some pieces of 'kirai' or the mangrove palm shoot rolled, dried and turned to make cigarettes, or the match sticks as a symbol of notes equivalent to RM1,000 each. The girl's side will make some requests on the man's side. 'Berian' or 'Tinunui' or dowry is obligatory as the symbol of the value of the girl's personality and based on the tradition worth RM1,000. The period to perform a marriage ceremony is one year. The man's family will request an adjournment of the marriage if the man encounters a financial problem.[13]

The 'belanja dapur' or kitchen expenses are estimated above RM5,000 and a moderate-fat buffalo. 'Adat Berian Tanah' or the land grant custom dowry is obligatory for the ethnic Dusun Lotud called 'Pinolusadan Do Aluwid', with the approved land taxation of 0.25 cents. The purpose of land grant dowry is for the construction of a house when the married couple has children. Based on tradition, if the bridegroom does not have assets like land, the 'berian four binukul' (valuable archaic items) will be mentioned with the value of RM1,000.00 as 'adat berian' and has fulfilled the terms.[13][3]

Ranau Dusuns

The Ranau Dusuns can be considered as more closely representative of the original Dusun stock than other sub-ethnic Dusun. This is due to the area in which they reside, the area is generally considered as the birthplace of the Dusun population, Nunuk Ragang. Most of the Dusun Ranau embrace Islam (especially in Kundasang owing to mass Islamisation of the population from animism during the colonial as well as USNO rules) and also Christianity (in which the largest single denomination amongst them would be the Sidang Injil Borneo, with minorities belonging to other denominations such as Roman Catholicism, Anglicanism, Seventh-day Adventism and so on).[14][15]

Tambunan Dusuns

Ethnically and linguistically related to the other Dusun tribes of the Bundu-Liwan valleys of the Crocker Range, this sub-ethnic group are religiously Christians (most of them being Roman Catholics since the late 19th and early 20th centuries), owing to mass Christianisation done by the Mill Hill Missionaries in today's Diocese of Keningau especially in their home district of Tambunan after converting their fellow Kadazan kinsfolk in Penampang as well as Papar, both located in Sabah's West Coast and the Archdiocese of Kota Kinabalu into the said religion, with minorities of this tribe's Christian populace being Protestants belonging to churches such as Sidang Injil Borneo, Seventh-day Adventist and many more other denominations, whilst a large minority of them being Muslims especially those resident in the border villages surrounding the neighbouring district of Ranau, owing to intermarriages and assimilation factors.

Dusun Tatana

The Dusun Tatana are different from all other Dusun people, their culture is similar to Chinese culture but mixed with some traditional Dusun customs and they are the only Dusun subethnic group who celebrate Lunar New Year as their predominant festival.[16][3] Kaamatan is less celebrated by them, but it is also widely celebrated once the month of May comes, since it is a statewide public holiday cum festival celebrated annually by the various tribes of the Kadazandusun and Murut group of peoples.

References

Citations

- Language: Kadazandusun, Malaysia. Discovery Channel. 2004. Retrieved 16 March 2022 – via UNESCO.

- Luering, H. L. E (1897). "A Vocabulary of the Dusun Language of Kimanis". Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (30): 1–29. JSTOR 41561584 – via Archive.org.

- "The Origin of Dusun Tribe in Sabah". TVOKM. 6 September 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- Yew, Chee Wei; Hoque, Mohd Zahirul; Pugh‐Kitingan, Jacqueline; et al. (2018). "Genetic Relatedness of Indigenous Ethnic Groups in Northern Borneo to Neighboring Populations from Southeast Asia, as Inferred from Genome‐Wide SNP Data". Annals of Human Genetics. 82 (4): 216–226. doi:10.1111/ahg.12246. PMID 29521412. S2CID 3780230.

- Estelle (29 May 2017). "Kaamatan: Tale of Harvest". AmazingBorneo. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Petronas (29 May 2017). "11 Things About Kaamatan and Gawai You Should Know Before Going to Sabah or Sarawak". Says. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Wayee, Crystal (1 May 2017). "Kadazandusun Food and Art". Padlet.com. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Traditional Costume of the Penampang Kadazan". Kadazandusun Cultural Association Sabah (KDCA). Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- "Kadazan Traditional Music and Dances". KadazanHomeland.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Evans (2012), p. 187.

- Tiwary, Shiv Shanker; Kumar, Rajeev, eds. (2009). "Nunuk Ragang". Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia and Its Tribes. Vol. 1. Anmol Publications. p. 224. ISBN 9788126138371.

- Reid (1997), p. 122.

- Murphy (29 March 2011). "Linangkit Cultural Village, Mysterious Past of Lotud People". MySabah.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- Jason George (1 June 2017). "Ranau Dusuns Hold Dearly to Their Tradition". New Sabah Times. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Masyarakat Dusun Ranau hidup harmoni walaupun berbeza agama". The Borneo Post. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- Tracy Patrick (18 February 2018). "Dusun Tribe Struggles to Keep Chinese New Year Tradition Alive". Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

Bibliography

- Evans, I. H. N. (2012) [1953]. "Introduction". The Religion of the Tempasuk Dusuns of North Borneo. Cambridge University Press. p. xxii. ISBN 9781107646032.

- Reid, Anthony (1997). "The Date and Provenance of the Franks Casket". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 28 (1): 120–136. doi:10.1017/S0022463400015204. JSTOR 20071905. S2CID 161168050.

Further reading

- Glyn-Jones, Monica (1953) The Dusun of the Penampang Plains, 2 vols. London.

- Gudgeon, L. W. W. (1913) British North Borneo, pp. 22 to 39. London: Adam and Charles Black.

- Hewett, Godfrey (1923) "The Dusuns of North Borneo" Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character Volume 95, Issue 666, pp. 157–163 Publication Date: 8/1923

- Ooi (2004) "Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East, Volume 1"

- Williams, Thomas Rhys (1966) The Dusun: A North Borneo Society NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

External links

![]() Media related to Dusun people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dusun people at Wikimedia Commons