Arado Ar 196

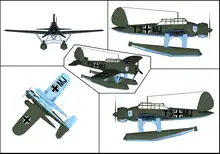

The Arado Ar 196 was a shipboard reconnaissance low-wing monoplane aircraft designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Arado. It was the standard observation floatplane of the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) throughout the Second World War, and was the only German seaplane to serve throughout the conflict.[1]

| Ar 196 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Luftwaffe Arado Ar 196A-2 (OU+AR) taxiing | |

| Role | Reconnaissance |

| Manufacturer | Arado |

| Designer | Walter Blume |

| First flight | May 1937 |

| Introduction | November, 1938 |

| Primary users | Kriegsmarine Bulgarian Air Force Finnish Air Force |

| Produced | 1938–44 |

| Number built | 541 |

The Ar 196 was designed in response to the Kriegsmarine's requirement to replace the Heinkel He 60 biplane after the intended successor, the He 114, had proved to be unsatisfactory. Arado submitted a monoplane design to the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (German Air Ministry, RLM) while all competing bids were for biplanes; the RLM decided to order four prototypes of the Ar 196 in late 1936. Testing of these prototypes during late 1937 revealed their favourable performance characteristics, leading to production being authorised and formal service tests commencing in the opening weeks of 1939. Starting in November 1939, production switched to the heavier land-based Ar 196 A-2 model; it would be followed by several more models until production of the type was terminated during August 1944.

All capital ships of the Kriegsmarine were equipped with Ar 196s. The aircraft was commonly used by numerous coastal squadrons, and as such continued to perform reconnaissance missions and submarine hunts into late 1944 across the Mediterranean, Aegean, and Black Seas. Perhaps their most noteworthy engagement was the involvement of two Ar 196s in the detection and capture of HMS Seal.[2] In addition to Germany, the Ar 196 was exported to the Bulgarian Air Force. Numerous examples were captured by the Allies, some of which were operated as late as 1955. Several Ar 196s have survived through to the twenty-first century, preserved for static display; none are known to be in an airworthy condition.

Design and development

Background

In 1933, the Kriegsmarine looked for a standardized shipboard observation floatplane. After a brief selection period, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (German Air Ministry, RLM) decided on the Heinkel He 60 biplane. This was one of a line of developments of a basic biplane airframe that appeared as a number of floatplanes, trainers, and fighters. Deliveries started in a matter of months.[3]

By early 1935, it was determined that the He 60's performance was lacking,[4] thus the RLM requested that Heinkel design a replacement aircraft, resulting in the He 114. The first prototype was powered by the Daimler-Benz DB 600 inline engine, but it was clear that supplies of this engine would be limited and the production versions turned to the BMW 132 radial engine instead. However, the aircraft proved to have only slightly better performance than the He 60 while its sea-handling was deemed to be poor and it did not meet strength requirements for catapult launches.[5] Rushed modifications resulted in a series of nine prototypes in an attempt to solve some of the problems, but they did not help much.[6] The Navy gave up, and the planes were eventually sold off to Romania, Spain and Sweden.

Submission and selection

During October 1936, the RLM requested for a He 114 replacement; the corresponding specification stipulated that the aircraft would use the BMW 132, and requested prototypes in both twin-float and single-float configurations.[5][6] Responses were received from Dornier, Gotha, Arado and Focke-Wulf. Heinkel declined to tender, contending that the He 114 could still be made to work.[7] With the exception of the Arado low-wing monoplane design, all submissions received were conventional biplanes. The Ar 196 was a semi-cantilever low-wing aircraft.[8] The design of its fuselage was reminiscent of the Arado Ar 95 maritime patrol biplane. The wings and forward fuselage were metal skinned, while a fabric covering was used for the empennage and rear fuselage.[8] Hydronalium, an alloy known for its resistance to corrosion in maritime environments, was extensively used throughout the aircraft The interior space of the floats was used to house fuel.[9]

Deeming Arado's submission to be the most modern and capable aircraft, the RLM placed an initial order for four prototypes.[7] These prototypes included a seaplane configured for catapult launches and stressed to perform diving bombing attacks.[5] The RLM was conservative by nature, thus they also ordered two of the Focke-Wulf Fw 62 designs as a backup measure. It quickly became clear that the Arado was performing effectively,[5] while also being easier to manufacture,[10] as such, only four prototypes of the Fw 62 were built.

Into flight

On 1 June 1937, the first prototype, Ar 196 V1, performed its maiden flight from the Plauer See.[10] Once its use in the flight test programme had been completed, Arado begun rebuilding V1 with the intention of attempting to set a new air speed record in its category; alterations included the installation of a more powerful BMW 132SA radial engine, a new low-profile canopy, and various aerodynamic refinements to the airframe. However, the RLM learnt of the intention and forbade Arado from proceeding on the grounds of maintaining military secrecy.[9]

All of the prototypes were delivered by the end of summer 1937, V1 and V2 with twin floats as A models, and V3 and V4 on a single float as B models. By the end of the year, all four were participating in flight testing. Testing revealed that, in comparison to the Fw 62, the Ar 196 was the superior aircraft, possessing lighter handling qualities, higher loading, a more rugged design, and better flight characteristics.[8] Both versions demonstrated excellent water handling and there seemed to be little to decide, one over the other. It was noted that the twin-float version exerted greater stress upon the wings,[11] yet, since there was a possibility of the smaller outrigger floats on the B models "digging in", the twin-float A model was ordered into production. Nevertheless, the two different float arrangements were designed to be interchangeable, along with cushioned ice skis.[11][12] A single additional prototype, V5, was produced in November 1938 to test final changes.

Ten A-0s were delivered in November and December 1938, permitting service tests to commence in the opening weeks of 1939.[11] These aircraft were provisioned with a single 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 15 machine gun at the rear seat for defence. Five similarly equipped B-0s were also delivered to land-based squadrons, which were promptly followed by 20 A-1 production models starting in June 1939, which were deemed to be sufficient to equip the surface fleet.[13] While production had fallen behind schedule by mid-1939, the programme was considered to be back on schedule by the end of the year.[13]

Further development

Starting in November 1939, production switched to the heavier land-based A-2 model. Intended for the coastal patrol role, it added shackles for the carriage of two 50 kg (110 lb) bombs, two 20 mm MG FF cannon in the wings, and a 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17 machine gun in the cowling.[14] Armament had not been addressed by the original specification for the aircraft, thus early production aircraft had been outfitted largely for aerial reconnaissance missions, particularly for the detection of enemy submarines. The addition of various weapons was a result of operational experiences where the aircraft had encountered enemies and found the absence of such armaments to be less than satisfying.[14]

A small series of fifteen A-4 models commenced production in December 1940.[1] Intended to be exclusively operated from the Kriegsmarine's capital ships, changes involved the strengthening of the airframe, the addition of another radio, and substituting propellers to a VDM model. The land-based A-3, which had additional strengthening of the airframe, was produced from the end of 1940 to autumn 1941. The final production version was the A-5 from late 1941, which changed radios and cockpit instruments, switched the rear gun to the much-improved MG 81Z with 2000 rounds of ammunition, retrofitted the existing cannon to the MG FF/M with extended 90 round magazines, added armour protection for the pilot and observer and strengthened the airframe. The A-5 also upgraded engine type to BMW 132W.[15][1]

To increase the rate of production to meet wartime demands, a license to produce the Ar 196 was arranged for the French aircraft manufacturer SNCASO; by 1942, 30 such aircraft were under construction by the company.[1] However, the quality of these aircraft was less than that of their German-built counterparts, which was believed to be due to the reluctance of SNCASO's French workforce.[16] Arado also adjusted their own manufacturing arrangements, intentionally decentralising and dispersing work wherever possible to minimise the impact of strategic bombing.[16] During 1940, Arado proposed an aerodynamically-refined model, referred to as the Ar 196C. Changes included the adoption of larger dual floats, which were to offset its greater all-up weight. While testing commenced in Hamburg and production was at one point scheduled to commence in 1942, quantity production of the Ar 196C never occurred.[1]

By the end of production in August 1944, a total of 541 Ar 196s (15 prototypes and 526 production models) had been constructed, about 100 of these being produced at SNCASO and Fokker plants.

Operational history

All capital ships of the Kriegsmarine were equipped with Ar 196s:

- The Bismarck-class battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz each carried four Ar 196s. The Bismarck had a very short operational career, the ship was lost during its first operation Rheinübung and did not have a chance to operate its aircraft. During the final stages of the operation, when Bismarck was surrounded by British forces close to the Atlantic coast of France, it was tried to launch an Ar 196 to bring the ships war diary and other reports to France. Only then it was discovered that the catapult was out of order because of battle damage sustained in the Battle of the Denmark Strait and thus the aircraft could not be launched.[17] The Tirpitz used one of her Ar 196s during Operation Sportpalast with limited success to attack shadowing British scout planes.[18]

- The Scharnhorst-class battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau initially had two catapults and three Ar 196s. Both ships operated together during the early stages of the war. During Operation Weserübung one of Scharnhorst's Ar 196s was launched at extreme range to Norway in order to convey reports and orders when the German ships had to keep radio silence at a crucial stage of the operation.[19] Similarly, one of Gneisenau's Arados brought reports to Norway after a first failed breakthrough attempt during Operation Berlin.[20]

- The Deutschland-class cruisers Deutschland, Admiral Scheer and Admiral Graf Spee were allocated two aircraft each, but during operations carried only one aircraft which was positioned on the catapult. These ships did not have an aircraft hangar. Admiral Graf Spee put its Ar 196 to good use during its raid on merchant shipping in the South Atlantic at the opening stage of the war.[21] The Ar 196 detected on 11 September the British heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland in time to avoid confrontation, and the airplane scouted successfully for British ships. But the aircraft broke down just before the Battle of the River Plate and was not able to warn Admiral Graf Spee of a patrolling British force, which eventually led to her scuttling at Montevideo.[22]

- The Admiral Hipper-class cruisers Admiral Hipper, Blücher and Prinz Eugen were equipped with one catapult and three Ar 196s.

The Ar 196 was a popular aircraft amongst pilots, who commonly found that it handled well both in the air and on the water. The aircraft became a staple of coastal squadrons, and as such continued to fly reconnaissance missions and submarine hunts into late 1944 across various theatres, including the Mediterranean, Aegean, and Black Seas.

The Ar 196 was involved in two particularly notable operations, these being the capture of HMS Seal and the interception of Royal Air Force Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley bombers. Although it was no match for a fighter, the aircraft was considerably better than its Allied counterparts and generally considered the best of its class. Despite this, it was apparent that floatplanes were at a disadvantage to most modern land-based aircraft.[16] Owing to its good handling on water, the Finnish Air Force used Ar 196 A-3s which were later upgraded to A-5s in mid-1944 for reconnaissance as well as supply runs, several troops could fit inside its fuselage.

Two Ar 196s were brought to Penang in Japanese-occupied Malaya. In March 1944, along with a Japanese Aichi E13A, these floatplanes formed the new East Asia Naval Special Service to assist both the German Monsun Gruppe and Japanese naval forces in the area. The aircraft were painted in Japanese livery and were operated by Luftwaffe pilots under the command of Oberleutnant Ulrich Horn.[23][24] On 18 February 1944, one of these Arados rescued thirtheen survivors of the German submarine UIT-23, by transferring them on its floats in several trips.[25]

Ar 196s in Allied hands

The first Ar 196 to be captured by the Allies was an example belonging to the German cruiser Admiral Hipper, which was captured in Lyngstad, Eide, by a Norwegian Marinens Flyvebaatfabrikk M.F.11 floatplane of the Trøndelag naval district on 8 April 1940, at the dawn of the Norwegian Campaign. After being towed to Kristiansund by the torpedo boat HNoMS Sild, it was used against its former owners, flying with Norwegian markings.[26] At 03:30 on 18 April, the Ar 196 was evacuated to the UK by a Royal Norwegian Navy Air Service pilot. The aircraft was shortly thereafter crashed by a British pilot while on transit to the Helensburgh naval air base for testing.[27] At the end of the conflict, at least one Ar 196 was left at a Norwegian airfield; it was kept in use as a liaison aircraft by the Royal Norwegian Air Force for roughly one year on the west coast.

During 1944–1945, Soviet forces captured many Arados along the Baltic coast of Poland and Germany. At Dassow, a spare parts depot was recovered also. After repairs, thirty-seven Ar 196s were fitted with Soviet radio equipment were integrated into the aviation element of the Soviet Border Guard. These were operated in the Baltic, Black Sea and Pacific coastal areas, serving until as late as 1955.[28] One Soviet 196 was re-engined with a Shvetsov ASh-62, in case of shortages of the BMW 132, but these shortages did not occur, and no more Ar 196s were re-engined.[29]

Operators

Norway – (captured)

Norway – (captured)

Aircraft on display

- Ar 196 A-5 (originally A-3) Werknummer 196 0219

- An aircraft operated by the Bulgarian Air Force is displayed at the Museum of Aviation, Plovdiv, Bulgaria.

- Ar 196 A-5, Werknummer 623 167

- An aircraft that formerly equipped the German cruiser Prinz Eugen is in storage at the Paul Garber Facility of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, and awaiting restoration.[30]

- Ar 196 A-5, Werknummer 623 183

- Another aircraft from the Prinz Eugen was displayed from 1949 to 1995 at the Naval Air Station Willow Grove, Pennsylvania and subsequently transferred to the National Naval Aviation Museum at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. The upper fuselage and canopy were damaged during transit, and it remained in storage awaiting restoration. In December 2012, it was packed into containers and shipped to Nordholz, Germany. Restoration began in August 2013, in time for that city's celebration for 100 years of German naval aviation. The plane, on long term loan from the National Naval Aviation Museum, will eventually be displayed at the Naval Air Wing 3 (Marinefliegergeschwader 3) headquarters at Nordholz Naval Airbase.[31][32]

- Arado Ar 196 A-2 Werknummer 196 0046 or 196 0048

The Aircraft Historical Museum, Sola, Norway, has on display an Ar 196 A-2 fuselage frame raised from the wreck of the German cruiser Blücher in Oslofjord.

Another aircraft is known to lie in the Jonsvatnet, a lake near Trondheim in Norway. A number of wartime German aircraft have been recovered from the lake, but the Ar 196 remains undisturbed as its crew were killed when it crashed there in 1940 and it has the status of a war grave.

A wrecked Ar 196 A-3, believed to be D1 + EH, was snagged by a fishing trawler off the island of Irakleia in 1982 at a depth of 91 meters. It was towed out of the fishing lanes to shallower waters (about 11 meters). The upside-down plane, with fuselage and wings mostly intact, has become a popular spot for scuba diving.[33]

Specifications (Ar 196 A-5)

Data from Arado Ar 196, Germany's Multi-Purpose Seaplane,[34] Arado, History of an Aircraft Company[35]

General characteristics

- Crew: two (pilot and observer)

- Length: 11 m (36 ft 1 in)

- Wingspan: 12.4 m (40 ft 8 in)

- Height: 4.45 m (14 ft 7 in)

- Wing area: 28.4 m2 (306 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 2,990 kg (6,592 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 3,720 kg (8,201 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × BMW 132W nine-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine, 782 kW (1,050 hp)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 332 km/h (206 mph, 179 kn)

- Range: 1,080 km (670 mi, 580 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 7,010 m (23,000 ft)

- Rate of climb: 6 m/s (1,200 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 98.2 kg/m2 (20.1 lb/sq ft)

- Power/mass: 0.235 kW/kg ( 0.143 hp/lb)

Armament

- Guns: * 1 × 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 81Z machine gun

- 1 × 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 17 machine gun

- 2 × 20 mm (0.787 in) MG FF/M cannon

- Bombs: * 2 × 50 kg (110.231 lb) bombs

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Aichi E13A

- Curtiss SC Seahawk

- Fairey Seafox

- IMAM Ro.43

- Nakajima A6M2-N

- Northrop N-3PB

- Supermarine Walrus

- Vought OS2U Kingfisher

Related lists

References

Citations

- Kranzhoff 1997, p. 84.

- Bekker. 1964 p. 91.

- de Jong 2021, pp. 6-7.

- de Jong 2021, pp. 7-8.

- Kranzhoff 1997, p. 81.

- de Jong 2021, pp. 8-9.

- de Jong 2021, p. 9.

- Kranzhoff 1997, pp. 81-82.

- de Jong 2021, p. 10.

- de Jong 2021, pp. 9-10.

- Kranzhoff 1997, p. 82.

- de Jong 2021, pp. 10-11.

- Kranzhoff 1997, p. 83.

- Kranzhoff 1997, pp. 83-84.

- Dabrowski 1997, .

- de Jong 2021, p. 13.

- Müllenheim-Rechberg 1980, pp. 148–149.

- Kemp 1998, p. 34.

- Bredemeier 1997, pp. 58–60.

- Bredemeier 1997, pp. 100–101.

- de Jong 2021, pp. 16-18.

- Stephen 1988, pp. 11–16.

- Horst H. Geerken (9 June 2017). Hitler's Asian Adventure. BoD – Books on Demand. pp. 375–376. ISBN 978-3-7386-3013-8.

- Brennecke 1996, p. 308.

- Brennecke 1996, p. 342.

- Sivertsen 1999, pp. 105, 115–122.

- Sivertsen 1999, p. 122.

- Kotelnikov, V. Stalin's Captives article in Fly Past magazine, February 2017, pp. 102-104.

- de Jong 2021, p. 88.

- "Arado Ar 196 A-5". Smithsonian: National Air and Space Museum: Arado Ar 196. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013.

- HCWinters (12 June 2013). "USA leihen Arado an das MFG aus". Cuxhavener Nachrichten. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "Kriegsflugzeug kehrt nach Deutschland zurück". Die Welt. 12 June 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Bardanis, Manolis; Lino, von Garzten. "Die Geschichte der Arado 196 von Herakleaia" (PDF). naxosdiving.com. Naxos Diving. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Dabrowski 1997, .

- Kranzhoff 1997, p. 85.

Bibliography

- Bredemeier, Heinrich (1997). Schlachtschiff Scharnhorst (in German) (5th ed.). Hamburg, Germany: Koehler. ISBN 3-7822-0592-8.

- Brennecke, Jochen (1996). Jäger-Gejagte. Deutsche U-Boote 1939-1945 (in German) (5th ed.). München: Wilhel Heyne Verlag. ISBN 3-453-02356-0.

- Dabrowski, Hans-Peter; Koos, Volker (1997). Arado Ar 196, Germany's Multi-Purpose Seaplane. Atglen, Pennsylvania, US: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 0-88740-481-2.

- de Jong, Peter (2021). Arado Ar 196 Units in Combat. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-47284-497-2.

- Kemp, Paul (1998). The Encyclopedia of 20th Century Conflict Sea Warfare. London, UK: Arms and Armour. ISBN 978-1-85409-221-2.

- Kranzhoff, Jörg Armin (1997). Arado, History of an Aircraft Company. Atglen, Pennsylvania, US: Schiffer Books. ISBN 0-7643-0293-0.

- Ledwoch, Janusz (1997). Arado 196 (Militaria 53) (in Polish). Warszawa, Poland: Wydawnictwo Militaria. ISBN 83-86209-87-9.

- Müllenheim-Rechberg, Burkhard von (1980). De ondergang van de Bismarck (in Dutch). De Boer Maritiem. ISBN 90-228-1836-5.

- Sivertsen, Svein Carl, ed. (1999). Jageren Sleipner i Romsdalsfjord sjøforsvarsdistrikt April 1940 (in Norwegian). Hundvåg, Norway: Sjømilitære Samfund ved Norsk Tidsskrift for Sjøvesen.

- Stephen, Martin (1988). Grove, Eric (ed.). Sea Battles in close-up : World War 2. London, UK: Ian Allan ltd. ISBN 0-7110-1596-1.