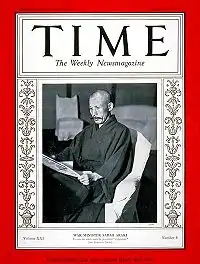

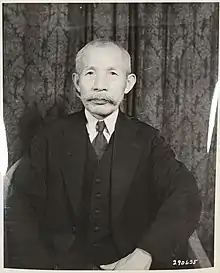

Sadao Araki

Baron Sadao Araki (荒木 貞夫, Araki Sadao, May 26, 1877 – November 2, 1966) was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War II. As one of the principal nationalist right-wing political theorists in the Empire of Japan, he was regarded as the leader of the radical faction within the politicized Imperial Japanese Army and served as Minister of War under Prime Minister Inukai. He later served as Minister of Education during the Konoe and Hiranuma administrations.

Sadao Araki | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | 荒木 貞夫 |

| Born | May 26, 1877 Komae, Tokyo, Empire of Japan |

| Died | November 2, 1966 (aged 89) Yoshino, Nara, Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1898–1936 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | 6th Division |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

| Other work | Minister of War, Minister of Education |

After World War II, he was convicted of war crimes and given a life sentence but was released in 1955.

Early life and career

Araki was born in Komae, Tokyo; his father was an ex-samurai retainer of the Hitotsubashi branch of the Tokugawa family. Araki graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in November 1897 and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in June of the following year.

Promoted to lieutenant in November 1900 and promoted to captain in June 1904, Araki served as company commander of the 1st Imperial Regiment during the Russo-Japanese War.

After the war, Araki returned to graduate from the Army Staff College at the head of his class. He served on the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff in April 1908 and served as a language officer stationed in Russia from November 1909 to May 1913, when he was made military attaché to Saint Petersburg during World War I. He was promoted to major in November 1909 and to lieutenant colonel in August 1915 and was assigned to the Kwantung Army.

Promoted to colonel on July 24, 1918, Araki served as a Staff Officer at Expeditionary Army Headquarters in Vladivostok in 1918 and 1919 during the Japanese Siberian Intervention against the Bolshevik Red Army, and was commander of the 23rd Infantry Regiment. During his time in Siberia, Araki carried out secret missions in the Russian Far East and in Lake Baikal.

Promoted to major general on March 17, 1923, Araki was made commander of the 8th Infantry Brigade. He served as Provost Marshal General from January 1924 to May 1925, wheby he rejoined the Army General Staff as a Bureau Chief. Araki was promoted to lieutenant general in July 1927 and became Commandant of the Army War College in August 1928.

Araki served as commander of the IJA 6th Division from 1929 through 1931, when he was appointed Deputy Inspector General of Military Training, one of the most prestigious posts within the army. He was promoted to the rank of full general in October 1933.[1]

Cabinet minister

On 31 December 1931, Araki was appointed Minister of War in the cabinet of Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai. However, in 1932, the May 15 Incident caused Inukai to be assassinated by ultranationalist navy officers for resisting the Army's war demands. Araki supported the assassins and called them "irrepressible patriots."[2] He also supported General Shiro Ishii and his biological warfare research project, Unit 731.

Prince Saionji, one of the emperor's closest and strongest advisors, attempted to stop the military takeover of the government. In a compromise, a naval officer, Admiral Makoto Saitō, became Prime Minister on 26 May. Araki remained as War Minister and made further demands on the new government. Later that month, Japan unveiled its new foreign policy, the Amau doctrine. The new policy became a blueprint for Japanese expansionism in Asia.

In September 1932, Araki started to become more outspoken in promoting totalitarianism, militarism, and expansionism. In a September 23 news conference, Araki first mentioned the philosophy of Kodoha ("The Imperial Way"), which linked the Emperor, the people, land, and morality as one indivisible entity, and he emphasized State Shinto. Araki also strongly promoted Seishin Kyoiku (spiritual training) for the army.

Araki became a member of the Supreme War Council but on 23 January 1934 resigned as War Minister because of ill health. He was ennobled with the title of baron (danshaku) in 1935 under the kazoku peerage system. In 1936, Kodoha-affiliated officers launched another rebellion in the February 26 Incident. The rebellion failed. However, unlike with previous rebellions, there were serious consequences. Nineteen of the rebel leaders were executed, and another 40 were imprisoned. Kodoha generals were purged from the Army, including Araki, who was forced to retire in March.

Fumimaro Konoe became Prime Minister in 1937. In 1938, Konoe appointed Araki as Education Minister, to offset the influence of the Toseiha ("Control Faction"). That placed him in an ideal position to promote militarism ideals through the national education system and in the general populace. Araki proposed the incorporation of the samurai code in the national education system. He promoted the use of the official academic text Kokutai no Hongi ("Japan's Fundamentals of National Policy"), and the "moral national bible" Shinmin no Michi ("The Path of Subjects"), an effective catechism on national, religious, cultural, social, and ideological topics. Araki continued to serve as Education Minister when Konoe was succeeded as Prime Minister by Hiranuma Kiichirō. He then continued to serve as an advisor to the government as a State Councillor.

Political career

In 1924, Araki founded the Kokuhonsha (Society for the Foundation of the State), a secret society containing some of the most powerful generals, admirals, and civilians dedicated to his statist philosophy that mixed totalitarianism, militarism, expansionism, and loyalty to the emperor. Araki was also theoretician of the even more radical Sakurakai (Cherry Blossom Society), which actively attempted to bring about a Showa Reformation by coups d'état.

As a colonel, Araki was the principal proponent of the Kodoha political faction (Imperial Benevolent Rule or Action Group) within the Japanese Army, together with Jinzaburo Mazaki, Heisuke Yanagawa, and Hideyoshi Obata. Their opposition was the Toseiha (Control Group), led by General Kazushige Ugaki. The Kodoha represented the radical and ultranationalist elements within the army. The Toseiha attempted to represent the more conservative moderates. Both groups had a common intellectual origin in the Double Leaf Society, a 1920s military thinking group supporting samurai ideals.

The groups were later to merge into the Imperial Way Faction (Kodoha) and incorporated a mixture of right-wing and national socialist ideas, particularly those of Kita Ikki and the pro-fascist philosophies of Nakano Seigo of which Araki was a leading member.

In January 1939, Araki became involved in the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement and revitalized it by having it sponsor public rallies, radio programs, printed propaganda, and discussion seminars at tonarigumi neighborhood associations.

Northern Expansion Doctrine

Within the Army, Araki was a supporter of the Northern Expansion Doctrine (Hokushin-ron), which proposed an attack on the Soviet Far East and Siberia.

An essential first step in the Hokushin-ron proposal was for Japan to seize control of Manchuria. Araki was a supporter of the unauthorized studies of China and the preparation of war scenarios by radical junior officer cliques within the Army. Through his connections with the Sakurakai, Araki intensified efforts to take the government away from civilian control, isolate the Emperor (Shōwa Reformation), unite the many secret societies, and appoint his close confidant Shigeru Honjō as commander of the Kwantung Army.

The Kwantung Army had 12,000 men available for the invasion of Manchuria at the time of the Mukden Incident but needed reinforcements. Araki arranged for another protégé, Chōsen Army commander Senjuro Hayashi, to be briefed to move his forces from Korea northward into Manchuria without permission from Tokyo in support of the Kwantung Army.

The plot to seize Manchuria proceeded as planned, and when presented by the fait accompli, all that Prime Minister Reijirō Wakatsuki could do was weakly protest and resign with his cabinet. When the new cabinet was formed, Araki, as War Minister, was the real power in Japan.

Postwar

After World War II, Araki was arrested by the American Occupation authorities and brought before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, where he was tried for Class A war crimes. He was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for conspiracy to wage aggressive war but was released from Sugamo Prison in 1955 for health reasons.[3] Like other Japanese peers, he was stripped of his hereditary peerage in 1947 upon the abolition of the Kazoku.

Araki died in 1966, and his grave is at Tama Cemetery, in Fuchū in Tokyo.

References

Citations

- Ammenthorp. The Generals of World War II

- Japan at War, Time-Life, 1980, p. 18

- Maga, Judgment at Tokyo: The Japanese War Crimes Trials

Sources

- Books

- Beasley, W.G. (2007). The Rise of Modern Japan, 3rd Edition: Political, Economic, and Social Change since 1850. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-23373-0.

- Samuels, Richard (2007). Securing Japan: Tokyo's Grand Strategy and the Future of East Asia. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4612-2.

- Maga, Timothy P. (2001). Judgment at Tokyo: The Japanese War Crimes Trials. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2177-9.

- Young, Louise (2001). Japan's Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism (Twentieth Century Japan: the Emergence of a World Power). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21934-1.

External links

- Ammenthorp, Steen. "Sadao, Araki". The Generals of World War II.

- National Diet Library. "Sadao, Araki". Portraits of Modern Historical Figures.

- Newspaper clippings about Sadao Araki in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW