Archaeological forgery

Archaeological forgery is the manufacture of supposedly ancient items that are sold to the antiquities market and may even end up in the collections of museums. It is related to art forgery.

A string of archaeological forgeries have usually followed news of prominent archaeological excavations. Historically, famous excavations like those in Crete, the Valley of the Kings in Egypt and Pompeii have caused the appearance of a number of forgeries supposedly spirited away from the dig. Those have been usually presented in the open market but some have also ended up in museum collections and as objects of serious historical study.

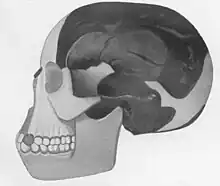

In recent times, forgeries of pre-Columbian pottery from South America have been very common. Other popular examples include Ancient Egyptian earthenware and supposed ancient Greek cheese. There have also been paleontological forgeries like the archaeoraptor or the Piltdown Man skull.

Motivations

Most archaeological forgeries are made for reasons similar to art forgeries – for financial gain. The monetary value of an item that is thought to be thousands of years old is higher than if the item were sold as a souvenir.

However, archaeological or paleontological forgers may have other motives; they may try to manufacture proof for their point of view or favorite theory (or against a point of view/theory they dislike), or to gain increased fame and prestige for themselves. If the intention is to create "proof" for religious history, it is considered pious fraud.

Detection

Investigators of archaeological forgery rely on the tools of archaeology in general. Since the age of the object is usually the most significant detail, they try to use radiocarbon dating or neutron activation analysis to find out the real age of the object.

Criticisms of antiquities trade

Some historians and archaeologists have strongly criticized the antiquities trade for putting profit and art collecting before scientific accuracy and veracity. This, in effect, favours the archaeological forgery. Allegedly, some of the items in prominent museum collections are of dubious or at least of unknown origin. Looters who rob archaeologically important places and supply the antiquities market are rarely concerned with exact dating and placement of the items. Antiquities dealers may also embellish a genuine item to make it more saleable. Sometimes traders may even sell items that are attributed to nonexistent cultures.

As is the case with art forgery, scholars and experts don't always agree on the authenticity of particular finds. Sometimes an entire research topic of a scholar may be based on finds that are later suspected as forgeries.

Known archaeological forgers

- Curzio Inghirami (1614—1655), 17th century Italian archaeologist and historian known as a forger of Etruscan artifacts.

- Alceo Dossena (1878–1937), 19th century Italian creator of many Archaic and Medieval statues

- Shinichi Fujimura (b. 1950), Japanese amateur archeologist who planted specimens on false layers to gain more prestige

- Brigido Lara (b. 1939-1940), Mexican forger of pre-Columbian antiquities

- Shaun Greenhalgh (b. 1961), a prolific and versatile British forger, who, with the help of his family, forged Ancient Egyptian statues, Roman silverware and Celtic gold jewelry among more modern artworks. Arrested in 2006 attempting to sell three Assyrian reliefs to the British Museum.

- Edward Simpson (b. 1815, fl. 1874), Victorian English forger of prehistoric flint tools. He sold forgeries to many British museums, including the Yorkshire Museum and the British Museum

- Moses Wilhelm Shapira (1830–1884), Ukrainian purveyor of fake biblical artifacts

- Tjerk Vermaning (1929–1986), Dutch amateur archaeologist whose Middle Paleolithic finds were declared forgeries

- James Mellaart (1925–2012), English archaeologist and author who is noted for his discovery of the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük in Turkey. After his death, it was discovered that he had forged many of his "finds", including murals and inscriptions used to discover the Çatalhöyük site.[1][2]

Known archaeological forgeries and hoaxes

- Calaveras Skull ("discovered" 1866), purported to prove that humans lived in North America as early as the Pliocene Epoch (5.33–2.58 MYA)

- Cardiff Giant ("discovered" 1869), carved gypsum statue presented as a petrified man, over 10 feet (3.0 m) tall

- Davenport Tablets (discovered 1877–1978), ornately carved slate tablets of purported Native American origin, but dubious authenticity

- Drake's Plate of Brass (discovered 1936), purported to have been left by Francis Drake after landing in Northern California in 1579

- "Egyptian mummy" ca. 1898, purchased from the estate of Confederate Colonel Breevoort Butler in the 1920s, the "mummy" was found to be a wooden frame covered with papier-mache; it is on display at the Old Capitol Museum in Jackson, Mississippi with its true nature openly revealed

- Etruscan terracotta warriors purchased by New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1915 to 1921; announced as forgeries in 1961

- Glozel tablets (archeological site discovered 1924), set of 100 inscribed ceramic tablets found in an authentic Medieval site among other artifacts of mixed authenticity and period

- Grave Creek Stone

- Japanese Paleolithic hoax

- Kinderhook plates

- Michigan relics

- Persian Princess, forged ancient mummy, possible murder victim[3]

- Piltdown Man

- Tiara of Saitaferne in Louvre

Cases generally believed by professional archaeologists to be forgeries or hoaxes

- America's Stonehenge

- Bat Creek inscription

- Bourne stone

- Burrows Cave

- Los Lunas Decalogue Stone

- Newark Holy Stones: Keystone tablet and the Newark Decalogue Stone

- Walam Olum

- Shroud of Turin

- Kensington Runestone

- Gosford Glyphs (discovered in the 1970s), Egyptian hieroglyphs carved into a pair of sandstone walls in New South Wales, Australia; widely acknowledged as modern forgeries, a minority of scholars use the glyphs as evidence of ancient Egyptian contact with Australia

Cases that several professional archaeologists believe to be forgeries or hoaxes

- James Ossuary

- Jehoash Inscription

- Ivory pomegranate

- The pieces discovered in 2005-2006 in Iruña-Veleia

Cases that some professional archaeologists believe to be forgeries or hoaxes

See also

References

- "James Mellaart: Pioneer…..and Forger" Popular Archaeology 11 Oct 2019

- http://www.talanta.nl/publications/previous-issues/2008-tm-201-%e2%97%8f-volume-xl-xlix/2018-%e2%97%8f-volume-50/ TALANTA, Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society 2018 - Volume L

- Romey, Kristin M.; Rose, Mark (January–February 2001). "Special Report: Saga of the Persian Princess". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 54 (1). Archived from the original on 2012-11-18. Retrieved 2019-06-08.