Aries (constellation)

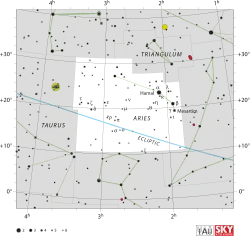

Aries is one of the constellations of the zodiac. It is located in the Northern celestial hemisphere between Pisces to the west and Taurus to the east. The name Aries is Latin for ram. Its old astronomical symbol is ![]() (♈︎). It is one of the 48 constellations described by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. It is a mid-sized constellation ranking 39th in overall size, with an area of 441 square degrees (1.1% of the celestial sphere).

(♈︎). It is one of the 48 constellations described by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. It is a mid-sized constellation ranking 39th in overall size, with an area of 441 square degrees (1.1% of the celestial sphere).

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Ari[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Arietis |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɛəriːz/, genitive /əˈraɪətəs/, /ˌæriˈɛtəs/ |

| Symbolism | the Ram |

| Right ascension | 01h 46m 37.3761s–03h 29m 42.4003s[2] |

| Declination | 31.2213154°–10.3632069°[2] |

| Area | 441[3] sq. deg. (39th) |

| Main stars | 4, 9 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 61 |

| Stars with planets | 6 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 2 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 2[lower-alpha 1] |

| Brightest star | Hamal (α Ari) (2.01m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers |

|

| Bordering constellations | |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −60°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of December. | |

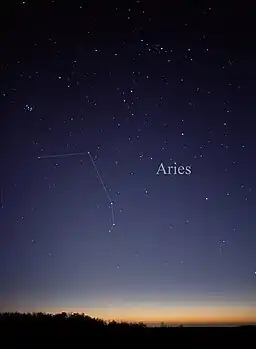

Aries has represented a ram since late Babylonian times. Before that, the stars of Aries formed a farmhand. Different cultures have incorporated the stars of Aries into different constellations including twin inspectors in China and a porpoise in the Marshall Islands. Aries is a relatively dim constellation, possessing only four bright stars: Hamal (Alpha Arietis, second magnitude), Sheratan (Beta Arietis, third magnitude), Mesarthim (Gamma Arietis, fourth magnitude), and 41 Arietis (also fourth magnitude). The few deep-sky objects within the constellation are quite faint and include several pairs of interacting galaxies. Several meteor showers appear to radiate from Aries, including the Daytime Arietids and the Epsilon Arietids.

History and mythology

Aries is now recognized as an official constellation, albeit as a specific region of the sky, by the International Astronomical Union. It was originally defined in ancient texts as a specific pattern of stars, and has remained a constellation since ancient times; it now includes the ancient pattern and the surrounding stars.[4] In the description of the Babylonian zodiac given in the clay tablets known as the MUL.APIN, the constellation, now known as Aries, was the final station along the ecliptic. The MUL.APIN was a comprehensive table of the rising and settings of stars, which likely served as an agricultural calendar. Modern-day Aries was known as MULLÚ.ḪUN.GÁ, "The Agrarian Worker" or "The Hired Man".[5] Although likely compiled in the 12th or 11th century BC, the MUL.APIN reflects a tradition that marks the Pleiades as the vernal equinox, which was the case with some precision at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age. The earliest identifiable reference to Aries as a distinct constellation comes from the boundary stones that date from 1350 to 1000 BC. On several boundary stones, a zodiacal ram figure is distinct from the other characters. The shift in identification from the constellation as the Agrarian Worker to the Ram likely occurred in later Babylonian tradition because of its growing association with Dumuzi the Shepherd. By the time the MUL.APIN was created—in 1000 BC—modern Aries was identified with both Dumuzi's ram and a hired labourer. The exact timing of this shift is difficult to determine due to the lack of images of Aries or other ram figures. [6]

In ancient Egyptian astronomy, Aries was associated with the god Amun-Ra, who was depicted as a man with a ram's head and represented fertility and creativity. Because it was the location of the vernal equinox, it was called the "Indicator of the Reborn Sun".[7] During the times of the year when Aries was prominent, priests would process statues of Amon-Ra to temples, a practice that was modified by Persian astronomers centuries later. Aries acquired the title of "Lord of the Head" in Egypt, referring to its symbolic and mythological importance.[8]

Aries was not fully accepted as a constellation until classical times.[9] In Hellenistic astrology, the constellation of Aries is associated with the golden ram of Greek mythology that rescued Phrixus and Helle on orders from Hermes, taking Phrixus to the land of Colchis.[10][11][12] Phrixus and Helle were the son and daughter of King Athamas and his first wife Nephele. The king's second wife, Ino, was jealous and wished to kill his children. To accomplish this, she induced famine in Boeotia, then falsified a message from the Oracle of Delphi that said Phrixus must be sacrificed to end the famine. Athamas was about to sacrifice his son atop Mount Laphystium when Aries, sent by Nephele, arrived.[13] Helle fell off of Aries's back in flight and drowned in the Dardanelles, also called the Hellespont in her honour. [3][10] [12]

Historically, Aries has been depicted as a crouched, wingless ram with its head turned towards Taurus. Ptolemy asserted in his Almagest that Hipparchus depicted Alpha Arietis as the ram's muzzle, though Ptolemy did not include it in his constellation figure. Instead, it was listed as an "unformed star", and denoted as "the star over the head". John Flamsteed, in his Atlas Coelestis, followed Ptolemy's description by mapping it above the figure's head.[13][14] Flamsteed followed the general convention of maps by depicting Aries lying down.[7] Astrologically, Aries has been associated with the head and its humors.[15] It was strongly associated with Mars, both the planet and the god. It was considered to govern Western Europe and Syria and to indicate a strong temper in a person.[16]

The First Point of Aries, the location of the vernal equinox, is named for the constellation. This is because the Sun crossed the celestial equator from south to north in Aries more than two millennia ago. Hipparchus defined it in 130 BC. as a point south of Gamma Arietis. Because of the precession of the equinoxes, the First Point of Aries has since moved into Pisces and will move into Aquarius by around 2600 AD. The Sun now appears in Aries from late April through mid-May, though the constellation is still associated with the beginning of spring.[11][13][17]

Medieval Muslim astronomers depicted Aries in various ways. Astronomers like al-Sufi saw the constellation as a ram, modelled on the precedent of Ptolemy. However, some Islamic celestial globes depicted Aries as a nondescript four-legged animal with what may be antlers instead of horns.[18] Some early Bedouin observers saw a ram elsewhere in the sky; this constellation featured the Pleiades as the ram's tail.[19] The generally accepted Arabic formation of Aries consisted of thirteen stars in a figure along with five "unformed" stars, four of which were over the animal's hindquarters and one of which was the disputed star over Aries's head.[20] Al-Sufi's depiction differed from both other Arab astronomers' and Flamsteed's, in that his Aries was running and looking behind itself.[7]

The obsolete constellations of Aries (Apes/Vespa/Lilium/Musca (Borealis)) all centred on the same the northern stars.[21] In 1612, Petrus Plancius introduced Apes, a constellation representing a bee. In 1624, the same stars were used by Jakob Bartsch as for Vespa, representing a wasp. In 1679, Augustin Royer used these stars for his constellation Lilium, representing the fleur-de-lis. None of these constellations became widely accepted. Johann Hevelius renamed the constellation "Musca" in 1690 in his Firmamentum Sobiescianum. To differentiate it from Musca, the southern fly, it was later renamed Musca Borealis but it did not gain acceptance and its stars were ultimately officially reabsorbed into Aries.[22] The asterism involved was 33, 35, 39, and 41 Arietis.[22]

In 1922, the International Astronomical Union defined its recommended three-letter abbreviation, "Ari".[1] The official boundaries of Aries were defined in 1930 by Eugène Delporte as a polygon of 12 segments. Its right ascension is between 1h 46.4m and 3h 29.4m and its declination is between 10.36° and 31.22° in the equatorial coordinate system.[23]

In non-Western astronomy

In traditional Chinese astronomy, stars from Aries were used in several constellations. The brightest stars—Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Arietis—formed a constellation called Lou (婁), variously translated as "bond", "lasso", and "sickle", which was associated with the ritual sacrifice of cattle. This name was shared by the 16th lunar mansion, the location of the full moon closest to the autumnal equinox. [13] This constellation has also been associated with harvest-time as it could represent a woman carrying a basket of food on her head.[7] 35, 39, and 41 Arietis were part of a constellation called Wei (胃), which represented a fat abdomen and was the namesake of the 17th lunar mansion, which represented granaries. Delta and Zeta Arietis were a part of the constellation Tianyin (天陰), thought to represent the Emperor's hunting partner. Zuogeng (左更), a constellation depicting a marsh and pond inspector, was composed of Mu, Nu, Omicron, Pi, and Sigma Arietis.[7][13] He was accompanied by Yeou-kang, a constellation depicting an official in charge of pasture distribution.[7]

In a similar system to the Chinese, the first lunar mansion in Hindu astronomy was called "Aswini", after the traditional names for Beta and Gamma Arietis, the Aswins. Because the Hindu new year began with the vernal equinox, the Rig Veda contains over 50 new-year's related hymns to the twins, making them some of the most prominent characters in the work. Aries itself was known as "Aja" and "Mesha".[16] In Hebrew astronomy Aries was named "Taleh"; it signified either Simeon or Gad, and generally symbolizes the "Lamb of the World". The neighboring Syrians named the constellation "Amru", and the bordering Turks named it "Kuzi".[16] Half a world away, in the Marshall Islands, several stars from Aries were incorporated into a constellation depicting a porpoise, along with stars from Cassiopeia, Andromeda, and Triangulum. Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Arietis formed the head of the porpoise, while stars from Andromeda formed the body and the bright stars of Cassiopeia formed the tail.[24] Other Polynesian peoples recognized Aries as a constellation. The Marquesas islanders called it Na-pai-ka; the Māori constellation Pipiri may correspond to modern Aries as well.[25] In indigenous Peruvian astronomy, a constellation with most of the same stars as Aries existed. It was called the "Market Moon" and the "Kneeling Terrace", as a reminder of when to hold the annual harvest festival, Ayri Huay. [16]

Features

Stars

Aries has three prominent stars forming an asterism, designated Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Arietis by Johann Bayer. Alpha (Hamal) and Beta (Sheratan) are commonly used for navigation.[26] There is also one other star above the fourth magnitude, 41 Arietis (Bharani[27]). α Arietis, called Hamal, is the brightest star in Aries. Its traditional name is derived from the Arabic word for "lamb" or "head of the ram" (ras al-hamal), which references Aries's mythological background.[17] With a spectral class of K2[12] and a luminosity class of III, it is an orange giant with an apparent visual magnitude of 2.00, which lies 66 light-years from Earth.[11][28] Hamal has a luminosity of 96 L☉ and its absolute magnitude is −0.1.[29]

β Arietis, also known as Sheratan, is a blue-white star with an apparent visual magnitude of 2.64. Its traditional name is derived from "sharatayn", the Arabic word for "the two signs", referring to both Beta and Gamma Arietis in their position as heralds of the vernal equinox. The two stars were known to the Bedouin as "qarna al-hamal", "horns of the ram".[30] It is 59 light-years from Earth.[31] It has a luminosity of 11 L☉ and its absolute magnitude is 2.1.[29] It is a spectroscopic binary star, one in which the companion star is only known through analysis of the spectra.[32] The spectral class of the primary is A5.[12] Hermann Carl Vogel determined that Sheratan was a spectroscopic binary in 1903; its orbit was determined by Hans Ludendorff in 1907. It has since been studied for its eccentric orbit.[32]

γ Arietis, with a common name of Mesarthim, is a binary star with two white-hued components, located in a rich field of magnitude 8–12 stars. Its traditional name has conflicting derivations. It may be derived from a corruption of "al-sharatan", the Arabic word meaning "pair" or a word for "fat ram".[13][17][33] However, it may also come from the Sanskrit for "first star of Aries" or the Hebrew for "ministerial servants", both of which are unusual languages of origin for star names.[17] Along with Beta Arietis, it was known to the Bedouin as "qarna al-hamal".[30] The primary is of magnitude 4.59 and the secondary is of magnitude 4.68.[29] The system is 164 light-years from Earth.[34] The two components are separated by 7.8 arcseconds,[3] and the system as a whole has an apparent magnitude of 3.9.[12] The primary has a luminosity of 60 L☉ and the secondary has a luminosity of 56 L☉; the primary is an A-type star with an absolute magnitude of 0.2 and the secondary is a B9-type star with an absolute magnitude of 0.4.[29] The angle between the two components is 1°.[3] Mesarthim was discovered to be a double star by Robert Hooke in 1664, one of the earliest such telescopic discoveries. The primary, γ1 Arietis, is an Alpha² Canum Venaticorum variable star that has a range of 0.02 magnitudes and a period of 2.607 days. It is unusual because of its strong silicon emission lines.[32]

The constellation is home to several double stars, including Epsilon, Lambda, and Pi Arietis. ε Arietis is a binary star with two white components. The primary is of magnitude 5.2 and the secondary is of magnitude 5.5. The system is 290 light-years from Earth.[11] Its overall magnitude is 4.63, and the primary has an absolute magnitude of 1.4. Its spectral class is A2. The two components are separated by 1.5 arcseconds.[29] λ Arietis is a wide double star with a white-hued primary and a yellow-hued secondary. The primary is of magnitude 4.8 and the secondary is of magnitude 7.3.[11] The primary is 129 light-years from Earth.[35] It has an absolute magnitude of 1.7 and a spectral class of F0.[29] The two components are separated by 36 arcseconds at an angle of 50°; the two stars are located 0.5° east of 7 Arietis.[3] π Arietis is a close binary star with a blue-white primary and a white secondary. The primary is of magnitude 5.3 and the secondary is of magnitude 8.5.[11] The primary is 776 light-years from Earth.[36] The primary itself is a wide double star with a separation of 25.2 arcseconds; the tertiary has a magnitude of 10.8. The primary and secondary are separated by 3.2 arcseconds.[29]

Most of the other stars in Aries visible to the naked eye have magnitudes between 3 and 5. δ Ari, called Boteïn, is a star of magnitude 4.35, 170 light-years away. It has an absolute magnitude of −0.1 and a spectral class of K2.[29][37] ζ Arietis is a star of magnitude 4.89, 263 light-years away. Its spectral class is A0 and its absolute magnitude is 0.0.[29][38] 14 Arietis is a star of magnitude 4.98, 288 light-years away. Its spectral class is F2 and its absolute magnitude is 0.6.[29][39] 39 Arietis (Lilii Borea[27]) is a similar star of magnitude 4.51, 172 light-years away. Its spectral class is K1 and its absolute magnitude is 0.0.[29][40] 35 Arietis is a dim star of magnitude 4.55, 343 light-years away. Its spectral class is B3 and its absolute magnitude is −1.7.[29][41] 41 Arietis, known both as c Arietis and Nair al Butain, is a brighter star of magnitude 3.63, 165 light-years away. Its spectral class is B8 and it has a luminosity of 105 L☉. Its absolute magnitude is −0.2.[29][42] 53 Arietis is a runaway star of magnitude 6.09, 815 light-years away.[32][43] Its spectral class is B2. It was likely ejected from the Orion Nebula approximately five million years ago, possibly due to supernovae.[32] Finally, Teegarden's Star is the closest star to Earth in Aries. It is a red dwarf of magnitude 15.14 and spectral class M6.5V. With a proper motion of 5.1 arcseconds per year, it is the 24th closest star to Earth overall.[44]

Aries has its share of variable stars, including R and U Arietis, Mira-type variable stars, and T Arietis, a semi-regular variable star. R Arietis is a Mira variable star that ranges in magnitude from a minimum of 13.7 to a maximum of 7.4 with a period of 186.8 days.[29] It is 4,080 light-years away.[45] U Arietis is another Mira variable star that ranges in magnitude from a minimum of 15.2 to a maximum of 7.2 with a period of 371.1 days.[29] T Arietis is a semiregular variable star that ranges in magnitude from a minimum of 11.3 to a maximum of 7.5 with a period of 317 days.[29] It is 1,630 light-years away.[46] One particularly interesting variable in Aries is SX Arietis, a rotating variable star considered to be the prototype of its class, helium variable stars. SX Arietis stars have very prominent emission lines of Helium I and Silicon III. They are normally main-sequence B0p—B9p stars, and their variations are not usually visible to the naked eye. Therefore, they are observed photometrically, usually having periods that fit in the course of one night. Similar to Alpha² Canum Venaticorum variables, SX Arietis stars have periodic changes in their light and magnetic field, which correspond to the periodic rotation; they differ from the Alpha² Canum Venaticorum variables in their higher temperature. There are between 39 and 49 SX Arietis variable stars currently known; ten are noted as being "uncertain" in the General Catalog of Variable Stars.[47]

Deep sky objects

NGC 772 is a spiral galaxy with an integrated magnitude of 10.3, located southeast of β Arietis and 15 arcminutes west of 15 Arietis.[12] It is a relatively bright galaxy and shows obvious nebulosity and ellipticity in an amateur telescope. It is 7.2 by 4.2 arcminutes, meaning that its surface brightness, magnitude 13.6, is significantly lower than its integrated magnitude. NGC 772 is a class SA(s)b galaxy, which means that it is an unbarred spiral galaxy without a ring that possesses a somewhat prominent bulge and spiral arms that are wound somewhat tightly.[3] The main arm, on the northwest side of the galaxy,[32] is home to many star forming regions; this is due to previous gravitational interactions with other galaxies. NGC 772 has a small companion galaxy, NGC 770, that is about 113,000 light-years away from the larger galaxy. The two galaxies together are also classified as Arp 78 in the Arp peculiar galaxy catalog. NGC 772 has a diameter of 240,000 light-years and the system is 114 million light-years from Earth.[48] Another spiral galaxy in Aries is NGC 673, a face-on class SAB(s)c galaxy. It is a weakly barred spiral galaxy with loosely wound arms. It has no ring and a faint bulge and is 2.5 by 1.9 arcminutes. It has two primary arms with fragments located farther from the core. 171,000 light-years in diameter, NGC 673 is 235 million light-years from Earth.[48]

NGC 678 and NGC 680 are a pair of galaxies in Aries that are only about 200,000 light-years apart. Part of the NGC 691 group of galaxies, both are at a distance of approximately 130 million light-years. NGC 678 is an edge-on spiral galaxy that is 4.5 by 0.8 arcminutes. NGC 680, an elliptical galaxy with an asymmetrical boundary, is the brighter of the two at magnitude 12.9; NGC 678 has a magnitude of 13.35. Both galaxies have bright cores, but NGC 678 is the larger galaxy at a diameter of 171,000 light-years; NGC 680 has a diameter of 72,000 light-years. NGC 678 is further distinguished by its prominent dust lane. NGC 691 itself is a spiral galaxy slightly inclined to our line of sight. It has multiple spiral arms and a bright core. Because it is so diffuse, it has a low surface brightness. It has a diameter of 126,000 light-years and is 124 million light-years away.[48] NGC 877 is the brightest member of an 8-galaxy group that also includes NGC 870, NGC 871, and NGC 876, with a magnitude of 12.53. It is 2.4 by 1.8 arcminutes and is 178 million light-years away with a diameter of 124,000 light-years. Its companion is NGC 876, which is about 103,000 light-years from the core of NGC 877. They are interacting gravitationally, as they are connected by a faint stream of gas and dust.[48] Arp 276 is a different pair of interacting galaxies in Aries, consisting of NGC 935 and IC 1801.[49]

NGC 821 is an E6 elliptical galaxy. It is unusual because it has hints of an early spiral structure, which is normally only found in lenticular and spiral galaxies. NGC 821 is 2.6 by 2.0 arcminutes and has a visual magnitude of 11.3. Its diameter is 61,000 light-years and it is 80 million light-years away.[48] Another unusual galaxy in Aries is Segue 2, a dwarf and satellite galaxy of the Milky Way, recently discovered to be a potential relic of the epoch of reionization.[50]

Meteor showers

Aries is home to several meteor showers. The Daytime Arietid meteor shower is one of the strongest meteor showers that occurs during the day, lasting from 22 May to 2 July. It is an annual shower associated with the Marsden group of comets that peaks on 7 June with a maximum zenithal hourly rate of 54 meteors.[51][52] Its parent body may be the asteroid Icarus. The meteors are sometimes visible before dawn, because the radiant is 32 degrees away from the Sun. They usually appear at a rate of 1–2 per hour as "earthgrazers", meteors that last several seconds and often begin at the horizon. Because most of the Daytime Arietids are not visible to the naked eye, they are observed in the radio spectrum. This is possible because of the ionized gas they leave in their wake.[53][54] Other meteor showers radiate from Aries during the day; these include the Daytime Epsilon Arietids and the Northern and Southern Daytime May Arietids.[55] The Jodrell Bank Observatory discovered the Daytime Arietids in 1947 when James Hey and G. S. Stewart adapted the World War II-era radar systems for meteor observations.[54]

The Delta Arietids are another meteor shower radiating from Aries. Peaking on 9 December with a low peak rate, the shower lasts from 8 December to 14 January, with the highest rates visible from 8 to 14 December. The average Delta Arietid meteor is very slow, with an average velocity of 13.2 kilometres (8.2 mi) per second. However, this shower sometimes produces bright fireballs.[56] This meteor shower has northern and southern components, both of which are likely associated with 1990 HA, a near-Earth asteroid.[57]

The Autumn Arietids also radiate from Aries. The shower lasts from 7 September to 27 October and peaks on 9 October. Its peak rate is low.[58] The Epsilon Arietids appear from 12 to 23 October.[7] Other meteor showers radiating from Aries include the October Delta Arietids, Daytime Epsilon Arietids, Daytime May Arietids, Sigma Arietids, Nu Arietids, and Beta Arietids.[55] The Sigma Arietids, a class IV meteor shower, are visible from 12 to 19 October, with a maximum zenithal hourly rate of less than two meteors per hour on 19 October.[59]

Planetary systems

Aries contains several stars with extrasolar planets. HIP 14810, a G5 type star, is orbited by three giant planets (those more than ten times the mass of Earth).[60] HD 12661, like HIP 14810, is a G-type main sequence star, slightly larger than the Sun, with two orbiting planets. One planet is 2.3 times the mass of Jupiter, and the other is 1.57 times the mass of Jupiter.[61] HD 20367 is a G0 type star, approximately the size of the Sun, with one orbiting planet. The planet, discovered in 2002, has a mass 1.07 times that of Jupiter and orbits every 500 days.[62] In 2019, scientists conducting the CARMENES survey at the Calar Alto Observatory announced evidence of two Earth-mass exoplanets orbiting Teegarden's star, located in Aries, within its habitable zone.[63] The star is a small red dwarf with only around a tenth of the mass and radius of the Sun.[63] It has a large radial velocity.[64]

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- The nearby stars that are named or otherwise known are Teegarden's star and TZ Arietis. The distance can be calculated from their parallax, listed in SIMBAD, by taking the inverse of the parallax and multiplying by 3.26.

Citations

- Russell 1922, p. 469.

- "Aries, constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Thompson & Thompson 2007, pp. 90–91.

- Pasachoff 2000, pp. 128–189.

- Evans 1998, p. 6.

- Rogers, Mesopotamian Traditions 1998.

- Staal 1988, pp. 36–41.

- Olcott 2004, p. 56.

- Rogers, Mediterranean Traditions 1998.

- Pasachoff 2000, pp. 84–85.

- Ridpath 2001, pp. 84–85.

- Moore & Tirion 1997, pp. 128–129.

- Ridpath, Star Tales Aries: The Ram.

- Evans 1998, pp. 41–42.

- Winterburn 2008, p. 5.

- Olcott 2004, pp. 57–58.

- Winterburn 2008, pp. 230–231.

- Savage-Smith & Belloli 1985, p. 80.

- Savage-Smith & Belloli 1985, p. 123.

- Savage-Smith & Belloli 1985, pp. 162–164.

- Staal 1988, p. 248.

- Ridpath, Star Tales Musca Borealis.

- IAU, The Constellations, Aries.

- Staal 1988, pp. 17–18.

- Makemson 1941, p. 279.

- Ridpath, Popular Names of Stars.

- "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- SIMBAD Alpha Arietis.

- Moore 2000, pp. 337–338.

- Savage-Smith & Belloli 1985, p. 121.

- SIMBAD Beta Arietis.

- Burnham 1978, pp. 245–252.

- Davis 1944.

- SIMBAD Gamma Arietis.

- SIMBAD Lambda Arietis.

- SIMBAD Pi Arietis.

- SIMBAD Delta Arietis.

- SIMBAD Zeta Arietis.

- SIMBAD 14 Arietis.

- SIMBAD 39 Arietis.

- SIMBAD 35 Arietis.

- SIMBAD 41 Arietis.

- SIMBAD 53 Arietis.

- RECONS, The 100 Nearest Star Systems.

- SIMBAD R Arietis.

- SIMBAD T Arietis.

- Good 2003, pp. 136–137.

- Bratton 2011, pp. 63–66.

- SIMBAD Arp 276.

- Belokurov et al. 2009.

- Jopek, "Daytime Arietids".

- Bakich 1995, p. 60.

- NASA, "June's Invisible Meteors".

- Jenniskens 2006, pp. 427–428.

- Jopek, "Meteor List".

- Levy 2007, p. 122.

- Langbroek 2003.

- Levy 2007, p. 119.

- Lunsford, Showers.

- Wright et al. 2009.

- ExoPlanet HD 12661.

- ExoPlanet HD 20367.

- Zechmeister, M.; et al. (2019). "The CARMENES search for exoplanets around M dwarfs". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 627: A49. arXiv:1906.07196. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935460. S2CID 189999121.

- Tanner, Angelle; et al. (November 2012). "Keck NIRSPEC Radial Velocity Observations of Late-M Dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 203 (1): 7. arXiv:1209.1772. Bibcode:2012ApJS..203...10T. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/203/1/10. S2CID 50864060.

Bibliography

- Bakich, Michael E. (1995). The Cambridge Guide to the Constellations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44921-2.

- Belokurov, V.; Walker, M. G.; Evans, N. W.; Gilmore, G.; Irwin, M. J.; Mateo, M.; Mayer, L.; Olszewski, E.; Bechtold, J.; Pickering, T. (August 2009). "The discovery of Segue 2: a prototype of the population of satellites of satellites". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 397 (4): 1748–1755. arXiv:0903.0818. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.397.1748B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15106.x. S2CID 20051174.

- Bratton, Mark (2011). The Complete Guide to the Herschel Objects: Sir William Herschel's Star Clusters, Nebulae, and Galaxies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76892-4.

- Burnham, Robert Jr. (1978). Burnham's Celestial Handbook (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-24063-3.

- Davis, George A. Jr. (1944). "The Pronunciations, Derivations, and Meanings of a Selected List of Star Names". Popular Science. 52: 8. Bibcode:1944PA.....52....8D.

- Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509539-5.

- Good, Gerry A. (2003). Observing Variable Stars. Springer. ISBN 978-1-85233-498-7.

- Jenniskens, Peter (2006). Meteor Showers and Their Parent Comets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85349-1.

- Langbroek, Marco (20 August 2003). "The November–December delta-Arietids and asteroid 1990 HA: On the trail of meteoroid stream with meteorite-sized members". WGN, Journal of the International Meteor Organization. 31 (6): 177–182. Bibcode:2003JIMO...31..177L.

- Levy, David H. (2007). David Levy's Guide to Observing Meteor Showers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69691-3.

- Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941). The Morning Star Rises: an account of Polynesian astronomy. Yale University Press. Bibcode:1941msra.book.....M.

- Moore, Patrick; Tirion, Wil (1997). Cambridge Guide to Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58582-8.

- Moore, Patrick (2000). The Data Book of Astronomy. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7503-0620-1.

- Olcott, William Tyler (2004). Star Lore: Myths, Legends, and Facts. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43581-7.

- Pasachoff, Jay M. (2000). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-93431-9.

- Ridpath, Ian (2001). Stars and Planets Guide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08913-3.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (1): 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: II. The Mediterranean Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (2): 79–89. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108...79R.

- Russell, Henry Norris (October 1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- Savage-Smith, Emilie; Belloli, Andrea P. A (1985). "Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their History, Construction, and Use". Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology. Smithsonian Institution Press (46): 1–354. doi:10.5479/si.00810258.46.1. hdl:10088/2445. S2CID 129450664.

- Staal, Julius D. W. (1988). The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars. The McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-04-5.

- Thompson, Robert Bruce; Thompson, Barbara Fritchman (2007). Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-52685-6.

- Winterburn, Emily (2008). The Stargazer's Guide: How to Read Our Night Sky. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-178969-4.

- Wright, J. T.; Fischer, D. A.; Ford, Eric B.; Veras, D.; Wang, J.; Henry, G. W.; Marcy, G. W.; Howard, A. W.; Johnson, John Asher (2009). "A Third Giant Planet Orbiting HIP 14810". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 699 (2): L97–L101. arXiv:0906.0567. Bibcode:2009ApJ...699L..97W. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/699/2/L97. S2CID 8075527.

Online sources

- "Aries Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Notes for star HD 12661". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Notes for star HD 20367". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Jopek, T. J. (3 March 2012). "Daytime Arietids". Meteor Data Center. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Jopek, T. J. (3 March 2012). "List of All Meteor Showers". Meteor Data Center. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Lunsford, Robert (16 January 2012). "2012 Meteor Shower List". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- "June's Invisible Meteors". NASA. 6 June 2000. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "The 100 Nearest Star Systems". Research Consortium on Nearby Stars. 1 January 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian. "Popular Names of Stars". Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Aries: The Ram". Star Tales. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Musca Borealis". Star Tales. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "Alpha Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Beta Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Gamma Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Lambda Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Pi Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Delta Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Zeta Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "14 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "39 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "35 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "41 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "53 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "R Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "T Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Arp 276". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

External links

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Aries

- The clickable Aries

- Star Tales – Aries

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Aries)