Orion (constellation)

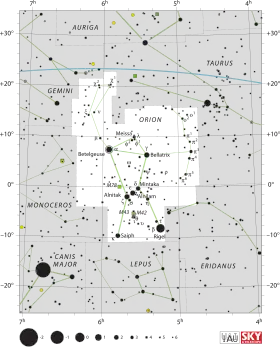

Orion is a prominent set of stars visible during winter in the northern celestial hemisphere. It is one of the 88 modern constellations; it was among the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. It is named for a hunter in Greek mythology.

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Ori |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Orionis |

| Pronunciation | /ɒˈraɪ.ən/ |

| Symbolism | Orion, the Hunter |

| Right ascension | 5h |

| Declination | +5° |

| Quadrant | NQ1 |

| Area | 594 sq. deg. (26th) |

| Main stars | 7 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 81 |

| Stars with planets | 10 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 8 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 8 |

| Brightest star | Rigel (β Ori) (0.12m) |

| Messier objects | 3 |

| Meteor showers | Orionids Chi Orionids |

| Bordering constellations | Gemini Taurus Eridanus Lepus Monoceros |

| Visible at latitudes between +85° and −75°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of January.  Click on to see large image. | |

Orion is most prominent during winter evenings in the Northern Hemisphere, as are five other constellations that have stars in the Winter Hexagon asterism. Orion's two brightest stars, Rigel (β) and Betelgeuse (α), are both among the brightest stars in the night sky; both are supergiants and slightly variable. There are a further six stars brighter than magnitude 3.0, including three making the short straight line of the Orion's Belt asterism. Orion also hosts the Orionids, the strongest meteor shower associated with Halley's Comet, and the Orion Nebula, one of the brightest nebula in the sky.

Characteristics

Orion is bordered by Taurus to the northwest, Eridanus to the southwest, Lepus to the south, Monoceros to the east, and Gemini to the northeast. Covering 594 square degrees, Orion ranks twenty-sixth of the 88 constellations in size. The constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 26 sides. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 04h 43.3m and 06h 25.5m , while the declination coordinates are between 22.87° and −10.97°.[1] The constellation's three-letter abbreviation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is "Ori".[2]

Orion is most visible in the evening sky from January to April,[3] winter in the Northern Hemisphere, and summer in the Southern Hemisphere. In the tropics (less than about 8° from the equator), the constellation transits at the zenith.

In the period May–July (summer in the Northern Hemisphere, winter in the Southern Hemisphere), Orion is in the daytime sky and thus invisible at most latitudes. However, for much of Antarctica in the Southern Hemisphere's winter months, the Sun is below the horizon even at midday. Stars (and thus Orion, but only the brightest stars) are then visible at twilight for a few hours around local noon, just in the brightest section of the sky low in the North where the Sun is just below the horizon. At the same time of day at the South Pole itself (Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station), Rigel is only 8° above the horizon, and the Belt sweeps just along it. In the Southern Hemisphere's summer months, when Orion is normally visible in the night sky, the constellation is actually not visible in Antarctica because the sun does not set at that time of year south of the Antarctic Circle.[4][5]

In countries close to the equator (e.g., Kenya, Indonesia, Colombia, Ecuador), Orion appears overhead in December around midnight and in the February evening sky.

Navigational aid

Orion is very useful as an aid to locating other stars. By extending the line of the Belt southeastward, Sirius (α CMa) can be found; northwestward, Aldebaran (α Tau). A line eastward across the two shoulders indicates the direction of Procyon (α CMi). A line from Rigel through Betelgeuse points to Castor and Pollux (α Gem and β Gem). Additionally, Rigel is part of the Winter Circle asterism. Sirius and Procyon, which may be located from Orion by following imaginary lines (see map), also are points in both the Winter Triangle and the Circle.[6]

Features

.jpg.webp)

Orion's seven brightest stars form a distinctive hourglass-shaped asterism, or pattern, in the night sky. Four stars—Rigel, Betelgeuse, Bellatrix, and Saiph—form a large roughly rectangular shape, at the center of which lies the three stars of Orion's Belt—Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka. His head is marked by an additional 8th star called Meissa, which is fairly bright to the observer. Descending from the "belt" is a smaller line of three stars, Orion's Sword (the middle of which is in fact not a star but the Orion Nebula), also known as the hunter's sword.

Many of the stars are luminous hot blue supergiants, with the stars of the belt and sword forming the Orion OB1 association. Standing out by its red hue, Betelgeuse may nevertheless be a runaway member of the same group.

Bright stars

- Betelgeuse, also designated Alpha Orionis, is a massive M-type red supergiant star nearing the end of its life. It is the second brightest star in Orion, and is a semiregular variable star.[7] It serves as the "right shoulder" of the hunter (assuming that he is facing the observer). It is generally the eleventh brightest star in the night sky, but this has varied between being the tenth brightest to the 23rd brightest by the end of 2019.[8][9] The end of its life is expected to result in a supernova explosion that will be highly visible from Earth, possibly outshining the Earth's moon and being visible during the day. This is most likely to occur within the next 100,000 years.[10]

- Rigel, also known as Beta Orionis, is a B-type blue supergiant that is the sixth brightest star in the night sky. Similar to Betelgeuse, Rigel is fusing heavy elements in its core and will pass its supergiant stage soon (on an astronomical timescale), either collapsing in the case of a supernova or shedding its outer layers and turning into a white dwarf. It serves as the left foot of the hunter.[11]

- Bellatrix is designated Gamma Orionis by Johann Bayer. It is the twenty-seventh brightest star in the night sky. Bellatrix is considered a B-type blue giant, though it is too small to explode in a supernova. Bellatrix's luminosity is derived from its high temperature rather than a large radius.[12] Bellatrix marks Orion's left shoulder and it means the "female warrior", and is sometimes known colloquially as the "Amazon Star".[13] It is the closest major star in Orion at only 244.6 light years from our solar system.

- Mintaka is designated Delta Orionis, despite being the faintest of the three stars in Orion's Belt. Its name means "the belt". It is a multiple star system, composed of a large B-type blue giant and a more massive O-type main-sequence star. The Mintaka system constitutes an eclipsing binary variable star, where the eclipse of one star over the other creates a dip in brightness. Mintaka is the westernmost of the three stars of Orion's Belt, as well as the northernmost.[6]

- Alnilam is designated Epsilon Orionis and is named for the Arabic phrase meaning "string of pearls".[6] It is the middle and brightest of the three stars of Orion's Belt. Alnilam is a B-type blue supergiant; despite being nearly twice as far from the Sun as the other two belt stars, its luminosity makes it nearly equal in magnitude. Alnilam is losing mass quickly, a consequence of its size. It is the farthest major star in Orion at 1,344 light years.

- Alnitak, meaning "the girdle", is designated Zeta Orionis, and is the easternmost star in Orion's Belt. It is a triple star system, with the primary star being a hot blue supergiant and the brightest class O star in the night sky.

- Saiph is designated Kappa Orionis by Bayer, and serves as Orion's right foot. It is of a similar distance and size to Rigel, but appears much fainter. It means the "sword of the giant"

- Meissa is designated Lambda Orionis, forms Orion's head, and is a multiple star with a combined apparent magnitude of 3.33. Its name means the "shining one".

| Proper name |

Bayer designation | Light years | Apparent magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betelgeuse | α Orionis | 548 | 0.50 |

| Rigel | β Orionis | 863 | 0.13 |

| Bellatrix | γ Orionis | 250 | 1.64 |

| Mintaka | δ Orionis | 1,200 | 2.23 |

| Alnilam | ε Orionis | 1,344 | 1.69 |

| Alnitak | ζ Orionis | 1,260 | 1.77 |

| Saiph | κ Orionis | 650 | 2.09 |

| Meissa | λ Orionis | 1,320 | 3.33 |

Belt

Orion's Belt or The Belt of Orion is an asterism within the constellation. It consists of the three bright stars Zeta (Alnitak), Epsilon (Alnilam), and Delta (Mintaka). Alnitak is around 800 light years away from earth and is 100,000 times more luminous than the Sun and shines with magnitude 1.8; much of its radiation is in the ultraviolet range, which the human eye cannot see.[14] Alnilam is approximately 2,000 light years away from Earth, shines with magnitude 1.70, and with ultraviolet light is 375,000 times more luminous than the Sun.[15] Mintaka is 915 light years away and shines with magnitude 2.21. It is 90,000 times more luminous than the Sun and is a double star: the two orbit each other every 5.73 days.[16] In the Northern Hemisphere, Orion's Belt is best visible in the night sky during the month of January around 9:00 pm, when it is approximately around the local meridian.[17]

Just southwest of Alnitak lies Sigma Orionis, a multiple star system composed of five stars that have a combined apparent magnitude of 3.7 and lying 1150 light years distant. Southwest of Mintaka lies the quadruple star Eta Orionis.

Sword

Orion's Sword contains the Orion Nebula, the Messier 43 nebula, the Running Man Nebula, and the stars Theta Orionis, Iota Orionis, and 42 Orionis.

Head

Three stars comprise a small triangle that marks the head. The apex is marked by Meissa (Lambda Orionis), a hot blue giant of spectral type O8 III and apparent magnitude 3.54, which lies some 1100 light years distant. Phi-1 and Phi-2 Orionis make up the base. Also nearby is the very young star FU Orionis.

Club

Stretching north from Betelgeuse are the stars that make up Orion's club. Mu Orionis marks the elbow, Nu and Xi mark the handle of the club, and Chi1 and Chi2 mark the end of the club. Just east of Chi1 is the Mira-type variable red giant U Orionis.

Shield

West from Bellatrix lie six stars all designated Pi Orionis (π1 Ori, π2 Ori, π3 Ori, π4 Ori, π5 Ori and π6 Ori) which make up Orion's shield.

Meteor showers

Around 20 October each year the Orionid meteor shower (Orionids) reaches its peak. Coming from the border with the constellation Gemini as many as 20 meteors per hour can be seen. The shower's parent body is Halley's Comet.[18]

Deep-sky objects

Hanging from Orion's belt is his sword, consisting of the multiple stars θ1 and θ2 Orionis, called the Trapezium and the Orion Nebula (M42). This is a spectacular object that can be clearly identified with the naked eye as something other than a star. Using binoculars, its clouds of nascent stars, luminous gas, and dust can be observed. The Trapezium cluster has many newborn stars, including several brown dwarfs, all of which are at an approximate distance of 1,500 light-years. Named for the four bright stars that form a trapezoid, it is largely illuminated by the brightest stars, which are only a few hundred thousand years old. Observations by the Chandra X-ray Observatory show both the extreme temperatures of the main stars—up to 60,000 kelvins—and the star forming regions still extant in the surrounding nebula.[19]

M78 (NGC 2068) is a nebula in Orion. With an overall magnitude of 8.0, it is significantly dimmer than the Great Orion Nebula that lies to its south; however, it is at approximately the same distance, at 1600 light-years from Earth. It can easily be mistaken for a comet in the eyepiece of a telescope. M78 is associated with the variable star V351 Orionis, whose magnitude changes are visible in very short periods of time.[20] Another fairly bright nebula in Orion is NGC 1999, also close to the Great Orion Nebula. It has an integrated magnitude of 10.5 and is 1500 light-years from Earth. The variable star V380 Orionis is embedded in NGC 1999.[21]

Another famous nebula is IC 434, the Horsehead Nebula, near ζ Orionis. It contains a dark dust cloud whose shape gives the nebula its name.

NGC 2174 is an emission nebula located 6400 light-years from Earth.

Besides these nebulae, surveying Orion with a small telescope will reveal a wealth of interesting deep-sky objects, including M43, M78, as well as multiple stars including Iota Orionis and Sigma Orionis. A larger telescope may reveal objects such as the Flame Nebula (NGC 2024), as well as fainter and tighter multiple stars and nebulae. Barnard's Loop can be seen on very dark nights or using long-exposure photography.

All of these nebulae are part of the larger Orion molecular cloud complex, which is located approximately 1,500 light-years away and is hundreds of light-years across. It is one of the most intense regions of stellar formation visible within our galaxy.

History and mythology

The distinctive pattern of Orion is recognized in numerous cultures around the world, and many myths are associated with it. Orion is used as a symbol in the modern world.

Ancient Near East

_Art.svg.png.webp)

The Babylonian star catalogues of the Late Bronze Age name Orion MULSIPA.ZI.AN.NA,[note 1] "The Heavenly Shepherd" or "True Shepherd of Anu" – Anu being the chief god of the heavenly realms.[22] The Babylonian constellation is sacred to Papshukal and Ninshubur, both minor gods fulfilling the role of 'messenger to the gods'. Papshukal is closely associated with the figure of a walking bird on Babylonian boundary stones, and on the star map the figure of the Rooster is located below and behind the figure of the True Shepherd—both constellations represent the herald of the gods, in his bird and human forms respectively.[23]

In ancient Egypt, the stars of Orion were regarded as a god, called Sah. Because Orion rises before Sirius, the star whose heliacal rising was the basis for the Solar Egyptian calendar, Sah was closely linked with Sopdet, the goddess who personified Sirius. The god Sopdu is said to be the son of Sah and Sopdet. Sah is syncretized with Osiris, while Sopdet is syncretized with Osiris' mythological wife, Isis. In the Pyramid Texts, from the 24th and 23rd centuries BC, Sah is one of many gods whose form the dead pharaoh is said to take in the afterlife.[24]

The Armenians identified their legendary patriarch and founder Hayk with Orion. Hayk is also the name of the Orion constellation in the Armenian translation of the Bible.[25]

The Bible mentions Orion three times, naming it "Kesil" (כסיל, literally – fool). Though, this name perhaps is etymologically connected with "Kislev", the name for the ninth month of the Hebrew calendar (i.e. November–December), which, in turn, may derive from the Hebrew root K-S-L as in the words "kesel, kisla" (כֵּסֶל, כִּסְלָה, hope, positiveness), i.e. hope for winter rains.: Job 9:9 ("He is the maker of the Bear and Orion"), Job 38:31 ("Can you loosen Orion's belt?"), and Amos 5:8 ("He who made the Pleiades and Orion").

In ancient Aram, the constellation was known as Nephîlā′, the Nephilim are said to be Orion's descendants.[26]

Greco-Roman antiquity

In Greek mythology, Orion was a gigantic, supernaturally strong hunter,[27] born to Euryale, a Gorgon, and Poseidon (Neptune), god of the sea. One myth recounts Gaia's rage at Orion, who dared to say that he would kill every animal on Earth. The angry goddess tried to dispatch Orion with a scorpion. This is given as the reason that the constellations of Scorpius and Orion are never in the sky at the same time. However, Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer, revived Orion with an antidote. This is said to be the reason that the constellation of Ophiuchus stands midway between the Scorpion and the Hunter in the sky.[28]

The constellation is mentioned in Horace's Odes (Ode 3.27.18), Homer's Odyssey (Book 5, line 283) and Iliad, and Virgil's Aeneid (Book 1, line 535)

Middle East

In medieval Muslim astronomy, Orion was known as al-jabbar, "the giant".[29] Orion's sixth brightest star, Saiph, is named from the Arabic, saif al-jabbar, meaning "sword of the giant".[30]

China

In China, Orion was one of the 28 lunar mansions Sieu (Xiù) (宿). It is known as Shen (參), literally meaning "three", for the stars of Orion's Belt. (See Chinese constellations)

The Chinese character 參 (pinyin shēn) originally meant the constellation Orion (Chinese: 參宿; pinyin: shēnxiù); its Shang dynasty version, over three millennia old, contains at the top a representation of the three stars of Orion's belt atop a man's head (the bottom portion representing the sound of the word was added later).[31]

India

The Rigveda refers to the Orion Constellation as Mriga (The Deer).[32]

Nataraja, 'the cosmic dancer', is often interpreted as the representation of Orion. Rudra, the Rigvedic form of Shiva, is the presiding deity of Ardra nakshatra (Betelgeuse) of Hindu astrology.[33]

The Jain Symbol carved in Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves, India in 1st century BCE[34] has striking resemblance with Orion.

Bugis sailors identified the three stars in Orion's Belt as tanra tellué, meaning "sign of three".[35]

European folklore

In old Hungarian tradition, Orion is known as "Archer" (Íjász), or "Reaper" (Kaszás). In recently rediscovered myths, he is called Nimrod (Hungarian: Nimród), the greatest hunter, father of the twins Hunor and Magor. The π and o stars (on upper right) form together the reflex bow or the lifted scythe. In other Hungarian traditions, Orion's belt is known as "Judge's stick" (Bírópálca).[36]

In Scandinavian tradition, Orion's belt was known as "Frigg's Distaff" (friggerock) or "Freyja's distaff".[37]

The Finns call Orion's belt and the stars below it "Väinämöinen's scythe" (Väinämöisen viikate).[38] Another name for the asterism of Alnilam, Alnitak and Mintaka is "Väinämöinen's Belt" (Väinämöisen vyö) and the stars "hanging" from the belt as "Kaleva's sword" (Kalevanmiekka).

In Siberia, the Chukchi people see Orion as a hunter; an arrow he has shot is represented by Aldebaran (Alpha Tauri), with the same figure as other Western depictions.[39]

There are claims in popular media that the Adorant from the Geißenklösterle cave, an ivory carving estimated to be 35,000 to 40,000 years old, is the first known depiction of the constellation. Scholars dismiss such interpretations, saying that perceived details such as a belt and sword derive from preexisting features in the grain structure of the ivory.[40][41][42][43]

Americas

The Seri people of northwestern Mexico call the three stars in the belt of Orion Hapj (a name denoting a hunter) which consists of three stars: Hap (mule deer), Haamoja (pronghorn), and Mojet (bighorn sheep). Hap is in the middle and has been shot by the hunter; its blood has dripped onto Tiburón Island.[44]

The same three stars are known in Spain and most of Latin America as "Las tres Marías" (Spanish for "The Three Marys"). In Puerto Rico, the three stars are known as the "Los Tres Reyes Magos" (Spanish for The three Wise Men).[45]

The Ojibwa (Chippewa) Native Americans call this constellation Kabibona'kan, the Winter Maker, as its presence in the night sky heralds winter.

To the Lakota Native Americans, Tayamnicankhu (Orion's Belt) is the spine of a bison. The great rectangle of Orion is the bison's ribs; the Pleiades star cluster in nearby Taurus is the bison's head; and Sirius in Canis Major, known as Tayamnisinte, is its tail. Another Lakota myth mentions that the bottom half of Orion, the Constellation of the Hand, represented the arm of a chief that was ripped off by the Thunder People as a punishment from the gods for his selfishness. His daughter offered to marry the person who can retrieve his arm from the sky, so the young warrior Fallen Star (whose father was a star and whose mother was human) returned his arm and married his daughter, symbolizing harmony between the gods and humanity with the help of the younger generation. The index finger is represented by Rigel; the Orion Nebula is the thumb; the Belt of Orion is the wrist; and the star Beta Eridani is the pinky finger.[46]

Austronesian

The seven primary stars of Orion make up the Polynesian constellation Heiheionakeiki which represents a child's string figure similar to a cat's cradle.[47] Several precolonial Filipinos referred to the belt region in particular as "balatik" (ballista) as it resembles a trap of the same name which fires arrows by itself and is usually used for catching pigs from the bush.[48][49][50][51] Spanish colonization later led to some ethnic groups referring to Orion's belt as "Tres Marias" or "Tatlong Maria."[52]

In Māori tradition, the star Rigel (known as Puanga or Puaka) is closely connected with the celebration of Matariki. The rising of Matariki (the Pleiades) and Rigel before sunrise in midwinter marks the start of the Māori year.[53]

Contemporary symbolism

The imagery of the belt and sword has found its way into popular western culture, for example in the form of the shoulder insignia of the 27th Infantry Division of the United States Army during both World Wars, probably owing to a pun on the name of the division's first commander, Major General John F. O'Ryan.[54][55]

The film distribution company Orion Pictures used the constellation as its logo.[56]

Depictions

In artistic renderings, the surrounding constellations are sometimes related to Orion: he is depicted standing next to the river Eridanus with his two hunting dogs Canis Major and Canis Minor, fighting Taurus. He is sometimes depicted hunting Lepus the hare. He sometimes is depicted to have a lion's hide in his hand.

There are alternative ways to visualise Orion. From the Southern Hemisphere, Orion is oriented south-upward, and the belt and sword are sometimes called the saucepan or pot in Australia and New Zealand. Orion's Belt is called Drie Konings (Three Kings) or the Drie Susters (Three Sisters) by Afrikaans speakers in South Africa[57] and are referred to as les Trois Rois (the Three Kings) in Daudet's Lettres de Mon Moulin (1866). The appellation Driekoningen (the Three Kings) is also often found in 17th- and 18th-century Dutch star charts and seaman's guides. The same three stars are known in Spain, Latin America, and the Philippines as "Las Tres Marías" (The Three Marys), and as "Los Tres Reyes Magos" (The three Wise Men) in Puerto Rico.[45]

Even traditional depictions of Orion have varied greatly. Cicero drew Orion in a similar fashion to the modern depiction. The Hunter held an unidentified animal skin aloft in his right hand; his hand was represented by Omicron2 Orionis and the skin was represented by the 5 stars designated Pi Orionis. Kappa and Beta Orionis represented his left and right knees, while Eta and Lambda Leporis were his left and right feet, respectively. As in the modern depiction, Delta, Epsilon, and Zeta represented his belt. His left shoulder was represented by Alpha Orionis, and Mu Orionis made up his left arm. Lambda Orionis was his head and Gamma, his right shoulder. The depiction of Hyginus was similar to that of Cicero, though the two differed in a few important areas. Cicero's animal skin became Hyginus's shield (Omicron and Pi Orionis), and instead of an arm marked out by Mu Orionis, he holds a club (Chi Orionis). His right leg is represented by Theta Orionis and his left leg is represented by Lambda, Mu, and Epsilon Leporis. Further Western European and Arabic depictions have followed these two models.[39]

Future

Orion is located on the celestial equator, but it will not always be so located due to the effects of precession of the Earth's axis. Orion lies well south of the ecliptic, and it only happens to lie on the celestial equator because the point on the ecliptic that corresponds to the June solstice is close to the border of Gemini and Taurus, to the north of Orion. Precession will eventually carry Orion further south, and by AD 14000, Orion will be far enough south that it will no longer be visible from the latitude of Great Britain.[58]

Further in the future, Orion's stars will gradually move away from the constellation due to proper motion. However, Orion's brightest stars all lie at a large distance from the Earth on an astronomical scale—much farther away than Sirius, for example. Orion will still be recognizable long after most of the other constellations—composed of relatively nearby stars—have distorted into new configurations, with the exception of a few of its stars eventually exploding as supernovae, for example Betelgeuse, which is predicted to explode sometime in the next million years.[59]

See also

- EURion constellation

- Hubble 3D (2010), IMAX film with an elaborate CGI "fly-through" of the Orion Nebula

- Orion (Chinese astronomy)

- Orion correlation theory

- Orvandil

- Urania

- Winter Hexagon

References

Explanatory notes

- The determiner glyph for "constellation" or "star" in these lists is MUL (𒀯). See Babylonian star catalogues.

Citations

- "Orion, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. Vol. 30. pp. 469–71. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- Ellyard, David; Tirion, Wil (2008) [1993]. The Southern Sky Guide (3rd ed.). Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-71405-1.

- "A Beginner's Guide to the Heavens in the Southern Hemisphere". dibonsmith.com.

- "The Evening Sky Map Southern Hemisphere Edition". skymaps.com.

- Staal 1988, p. 61.

- "Variable Star of the Month, Alpha Ori". Variable Star of the Season. American Association of Variable Star Observers. 2000. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- "Waiting for Betelgeuse: What's Up with the Tempestuous Star?". December 26, 2019.

- Dolan, Chris. "Betelgeuse". Archived from the original on 2011-11-24. Retrieved 2023-08-06.

- Prior, Ryan (26 December 2019). "A giant red star is acting weird and scientists think it may be about to explode". CNN.

- "Rigel". Jim Kaler's Stars. University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. 2009. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- "Bellatrix". Jim Kaler's Stars. University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. 2009. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- Dolan, Chris. "Bellatrix". Archived from the original on 2011-11-30. Retrieved 2023-08-06.

- "Alnitak". Stars.astro.illinois.edu. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- "Alnilam". Jim Kaler's Stars. University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-11-24. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- "Mintaka". Jim Kaler's Stars. University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-11-24. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- Dolan, Chris. "Orion". Archived from the original on 2011-12-07. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- Jenniskens, Peter (September 2012). "Mapping Meteoroid Orbits: New Meteor Showers Discovered". Sky & Telescope. p. 22.

- Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe (1st ed.). Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

- Levy 2005, pp. 99–100.

- Levy 2005, p. 107.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108: 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- Babylonian Star-lore by Gavin White, Solaria Pubs, 2008, page 218ff & 170

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 127, 211

- Kurkjian, Vahan (1968). "History of Armenia". uchicago.edu. Michigan. 8.

- Peake's commentary on the Bible, 1962, page 260 section 221f.

- "Star Tales – Orion". www.ianridpath.com.

- Staal 1988, pp. 61–62.

- Metlitzki, Dorothee (1977). The Matter of Araby in Medieval England. United States: Yale University Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-300-11410-9.

- Kaler, James B., "SAIPH (Kappa Orionis)", Stars, University of Illinois, retrieved 2012-01-27

- 漢語大字典 Hànyǔ Dàzìdiǎn (in Chinese), 1992 (p.163). 湖北辭書出版社和四川辭書出版社 Húbĕi Cishu Chūbǎnshè and Sìchuān Cishu Chūbǎnshè, re-published in traditional character form by 建宏出版社 Jiànhóng Publ. in Taipei, Taiwan; ISBN 957-813-478-9

- Holay, P. V. (1998). "Vedic astronomers". Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India. 26: 91–106. Bibcode:1998BASI...26...91H. doi:10.1080/1468936042000282726821. S2CID 26503807.

- Srinivasan, Sharada (1998). "Vedic astronomers". World Archaeology. 36: 432–50. Bibcode:1998BASI...26...91H. doi:10.1080/1468936042000282726821. S2CID 26503807.

- ""Must See" Indian Heritage". asimustsee.nic.in. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- Kelley, David H.; Milone, Eugene F.; Aveni, A.F. (2011). Exploring Ancient Skies: A Survey of Ancient and Cultural Astronomy. New York, New York: Springer. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-4419-7623-9.

- Toroczkai-Wigand Ede : Öreg csillagok ("Old stars"), Hungary (1915) reedited with Műszaki Könyvkiadó METRUM (1988).

- Schön, Ebbe. (2004). Asa-Tors hammare, Gudar och jättar i tro och tradition. Fält & Hässler, Värnamo. p. 228.

- Elo, Ismo. "Tähdet ja tähdistöt". Ursa.fi. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- Staal 1988, p. 63.

- The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines, ed. Timothy Insoll, 2017, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199675619, 9780199675616, google books

- Rappenglück, Michael (2001). "The Anthropoid in the Sky: Does a 32,000 Years Old Ivory Plate Show the Constellation Orion Combined with a Pregnancy Calendar". Symbols, Calendars and Orientations: Legacies of Astronomy in Culture. IXth Annual meeting of the European Society for Astronomy in Culture (SEAC). Uppsala Astronomical Observatory. pp. 51–55.

- "The Decorated Plate of the Geißenklösterle, Germany". UNESCO: Portal to the Heritage of Astronomy. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Whitehouse, David (January 21, 2003). "'Oldest star chart' found". BBC. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Moser, Mary B.; Marlett, Stephen A. (2005). Comcáac quih yaza quih hant ihíip hac: Diccionario seri-español-inglés (PDF) (in Spanish and English). Hermosillo, Sonora and Mexico City: Universidad de Sonora and Plaza y Valdés Editores.

- "Home – El Nuevo Día". Elnuevodia.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- "Windows to the Universe". Windows2universe.org. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- http://pvs.kcc.hawaii.edu/ike/hookele/hawaiian_star_lines.html#ke_ka_o_makalii

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City, Manila, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 124. ISBN 9789715501354.

- Encarnación, Juan Félix (1885). Diccionario bisaya español [Texto impreso] (in Spanish and Cebuano). p. 30.

- https://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/pssr/article/view/1287/1833#page=5

- https://www.flipscience.ph/space/pinoy-ethnoastronomy/

- https://philippineculturaleducation.com.ph/balatik/

- "Puanga: The star that heralds Matariki". Tertiary Education Union/Te Hautū Kahurangi. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Hart, Albert Bushnell (1920). Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume 5. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 358.

- Moss, James Alfred; Howland, Harry Samuel (1920). America in Battle: With Guide to the American Battlefields in France and Belgium. Menasha, Wisconsin: Geo. Banta Publishing Co. p. 555.

- Kim, Wook (2012-09-21). "Mountain to Moon: 10 Movie Studio Logos and the Stories Behind Them". Time.com. Retrieved 2015-09-22.

- "The Three Kings and the Cape Clouds: Two astronomical puzzles". psychohistorian.org. Archived from the original on 2010-01-29. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- "Precession". Myweb.tiscali.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- Wilkins, Alasdair (20 January 2011). "Earth may soon have a second sun". io9. Space Porn.

Bibliography

- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-361-0.

- Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (2007). Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London. ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9. Princeton Universitl Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

- Staal, Julius D. W. (1988), The New Patterns in the Sky, McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company, ISBN 0-939923-04-1

External links

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Orion

- Melbourne Planetarium: Orion Sky Tour

- Views of Orion from other places in our Galaxy

- The clickable Orion

- Ian Ridpath's Star Tales – Orion

- Deep Widefield image of Orion

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Orion: Head to Toe (23 October 2010)

- Beautiful Astrophoto: Zoom Into Orion

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Orion)