Culture of Morocco

The culture of Morocco is a blend of Arab, Amazighs, Andalusian cultures, with African, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences.[1][2][3][4] It represents and is shaped by a convergence of influences throughout history. This sphere may include, among others, the fields of personal or collective behaviors, language, customs, knowledge, beliefs, arts, legislation, gastronomy, music, poetry, architecture, etc. While Morocco started to be stably predominantly Sunni Muslim starting from 9th–10th century AD, in the Almoravids empire period, a very significant Andalusian culture was imported and contributed to the shaping of Moroccan culture.[5] Another major influx of Andalusian culture was brought by Andalusians with them following their expulsion from Al-andalus to North Africa after the Reconquista.[3] In antiquity, starting from the second century A.D and up to the seventh, a rural Donatist Christianity was present, along an urban still-in-the-making Roman Catholicism.[6][7] All of the cultural super strata tend to rely on a multi-millennial aboriginal Berber substratum still strongly present and dating back to prehistoric times.

.jpg.webp)

The linguistic landscape of Morocco is complex. It generally tends to be horizontally diverse and vertically stratified. It is though possible to broadly classify it into two main components: Arab and Berber. It is hardly possible to speculate about the origin of Berber languages as it is traced back to low antiquity and prehistoric times.[8] The Semitic influence, on the contrary, can be fairly documented by archaeological evidence.[9] It came in two waves: Canaanite, in its Punic, Carthaginian and Hebrew historic varieties, from the ninth century B.C and up to high antiquity, and Arabic, during the low Middle Ages, starting from the seventh century A.D. The two Semitic languages being close, both in syntax and vocabulary it is hard to tell them apart as to who influenced more the structure of the modern Moroccan Arabic dialect.[10] The Arab conquerors having certainly encountered large romanized urban Punic population as they advanced.[11] In any case, the linguistic and cultural identity of Morocco, just as its geography would predict, is the result of the encounter of three main circles: Arab, Berber, and Western Mediterranean European.

While the two official languages of Morocco are Standard Arabic and Standard Moroccan Berber, according to the 2014 general census, 92% of Moroccans speak Moroccan Arabic (Darija) as a native language.[12] About 26%[12] of the population speaks a Berber language, in its Tarifit, Tamazight, or Tashelhit varieties.[13][14]

Language

Modern Standard Arabic and Standard Moroccan Berber are the official languages of Morocco,[15] while Moroccan Arabic is the national vernacular dialect;[16] Berber languages are spoken in some mountain areas, such as Tarifit, spoken by 1.2 million,[17] Central Atlas Tamazight, spoken by 2.3 million,[17] and Tashelhit, spoken by 3 to 4.7 million.[17] Varieties of Judeo-Arabic have also traditionally been spoken in Morocco.[18] Foreign languages, particularly French, English, and Spanish, are also spoken in urban centers such as Tangier or Casablanca. With all of these languages, code-switching is an omnipresent phenomenon in Moroccan speech and media.[19]

Darija

Classical Arabic, a formal rather than natural language, is used primarily in formal, academic, and religious settings.[20] Moroccan Arabic, in its various regional and contextual forms, is used more often in casual situations, at home, and on the street.[21] Hassaniya is another dialect of Arabic spoken in the south of Morocco.[22]

Berber languages

There are three main varieties of Berber languages spoken in Morocco. Tashelhit (also known locally as Soussia) is spoken in southwest Morocco, including the High Atlas and the Sous valley. Central Atlas Tamazight is spoken in the Middle Atlas and southeast Morocco; for example, around Khenifra and Midelt. Tarifit is spoken in the Rif area of northern Morocco in towns like Nador, Al Hoceima, and Ajdir.[23][24]

Literature

Moroccan literature is the literature produced by people who lived in or were culturally connected to Morocco and the historical states that have existed partially or entirely within the geographical area that is now Morocco. Most of what is known as Moroccan literature was created since the arrival of Islam in the 8th century.[25] Moroccan literature was historically and mainly written in Arabic.[26]

Music

Moroccan music is characterized by its great diversity from one region to another. It includes Arabic music genres, such as chaâbi and aita in the Atlantic plains (Doukkala-Abda, Chaouia-Ouardigha, Rehamna), melhoun in the cities associated with al-Andalus (Meknes, Fes, Salé, Tetouan, Oujda...), and Hassani in the Moroccan Sahara. There is also Berber music such as the Rif reggada, the ahidus of the Middle Atlas and the Souss ahwash. In the South there is also deqqa Marrakshia and gnawa. In addition, young people synthesize the Moroccan spirit with influences from around the world (blues, rock, metal, reggae, Moroccan rap, etc.).

Tarab al-āla (طرب الآلة lit. "joy of the instrument") is a celebrated musical style in Morocco, a result of a large migration of Muslims from Valencia to Moroccan cities and especially Fes.[27] The Fessi āla style uses the Moroccan forms of the Andalusi nubah melodical arrangements.[28] While this musical style is sometimes popularly referred to as Andalusi music, specialists prefer the name āla (آلة "instrument") to differentiate it from the Sufi tradition of samā', which is purely vocal, and to deëmphasize its relationship with Europe.[29] Mohammed al-Haik's 18th century songbook Kunnash al-Haik, is a seminal text of the āla tradition.[29] Traditional songs such as "Shams al-'Ashiya" are still played at celebrations and formal events.[30] Dar ul-Aala in Casablanca is a museum and conservatory dedicated to this musical heritage. Another style of music derived from the musical traditions of al-Andalus is Gharnati music.[31][32]

A genre known as Contemporary Andalusian Music and art is the brainchild of Morisco visual artist/composer/oudist Tarik Banzi, founder of the Al-Andalus Ensemble.

Chaabi ("popular") is a music consisting of numerous varieties which are descended from the multifarious forms of Moroccan folk music. Chaabi was originally performed in markets, but is now found at any celebration or meeting.

Popular Western forms of music are becoming increasingly popular in Morocco, such as fusion, rock, country, metal and, in particular, hip hop.

Morocco participated in the 1980 Eurovision Song Contest, where it finished in the penultimate position.

Visual arts

The decorative arts have a long and important history in Morocco. One of the traditional elements of artistic expression in Morocco is Maghrebi-Andalusian art and architecture.[33] Carved plaster Arabesques, zellige tilework, carved wood, and other expressions of Islamic geometric patterns are typical features of this style.[34]

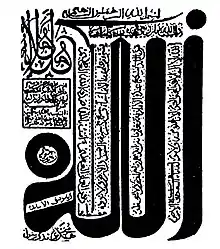

Maghrebi Arabic script is an important feature of the history of visual art in Morocco.[35] While some aspects of Maghrebi script are codified and prescribed, there have also been innovations, such as those by the 19th century calligrapher Muhammad al-Qandusi.[36] Muhammad Ben Ali Rabati was one of the first Moroccans to paint in a European style.[37]

Modern art

Hamid Irbouh identifies three groups within Moroccan modernism: the Populists, the Nativists, and the Bipictorialists. Among the Populists—usually self-trained artists who received support from French and American patrons and depicted everyday vernacular life—were artists such as Ahmed Louardighi, Hassan El Glaoui, Ahmed Drissi, and Fatima Hassan El Farouj.[38] The Nativists—active in the 1960s and led by Farid Belkahia and other members of the Casablanca School, such as Mohamed Melehi and Mohamed Chabâa—sought to break entirely with the West in general and with France in particular.[38][39] The Bipictorialists, including Ahmed Cherkaoui and Jilali Gharbaoui, entered in dialog with Moroccan, French, and Western influences, working toward a reconciliation of the various dimensions of postcolonial Moroccan identity.[38]

Contemporary art

Contemporary art in Morocco is still developing. with considerable potential for growth. Since the 1990s–2000s Moroccan cities have welcomed institutions that contribute to the diffusion of contemporary art and the visual arts: L'appartement 22 and Radio Apartment 22 in Rabat,[40][41] the Cinémathèque de Tanger in Tangier, La Source du Lion in Casablanca, Dar Al-Ma'mûn residency and center, the Marrakech Art Fair, and the Marrakech Biennale, all in Marrakech.

Local art galleries such as Galerie Villa Delaporte, Atelier 21, Galerie Matisse and Galerie FJ are also platforms showing contemporary artwork and contributing to its development.[42]

The global art market also influences the development and visibility of contemporary art in Morocco; international exhibitions such as "Africa Remix" (2004) and "Uneven Geographies" (2010) featured contemporary artists from North Africa, including Moroccan ones. Regional events such as the Dakar Biennale (or Dak'Art – Biennale de l'Art Africain Contemporain), a major contemporary African art exhibition, gives greater visibility to artists from the African continent.

Moroccan artists and their initiatives

Artists born in Morocco or with Moroccan origins include Mounir Fatmi, Latifa Echackhch, Mohamed El Baz, Bouchra Khalili, Majida Khattari, Mehdi-Georges Lahlou, and Younes Baba-Ali.[44]

Moroccan artists have devised several initiatives to help develop a contemporary art market in the country. For example, Hassan Darsi created La Source du Lion in 1995, an art studio that welcomes artists-in-residence, and Bouchra Khalili and Yto Barrada founded the Cinémathèque de Tanger in 2003, which is dedicated to promoting Moroccan cinematographic culture.[45] A group of seven Moroccan artists, among them Amina Benbouchta, Hassan Echair, Jamila Lamrani, Safâa Erruas and Younès Rahmoun, formed "Collectif 212" to exhibit their work at Le Cube, an independent art room. Their first major show was in 2006 at the exhibition Un Siècle de peinture au Maroc [A century of painting in Morocco] when the new premises of the French Institute of Rabat (L'Institut Français de Rabat) were officially opened.[46] They committed to creating artistic experiences in the context of Moroccan culture, as well as collaborating with other artists such as Hicham Benohoud.

The young local artists Batoul Shim and Karim Rafi participated in the "Working for Change" project, which aims to create art expressive of Moroccan culture, during the 2011 Venice Biennale.[47]

Art market

There is a burgeoning market for modern & contemporary art. The art movement began over 50 years ago at the center of Marrakech, in the bustling market place of Jemaa el-Fna, when a group of abstract artists[48] got together and exhibited their work. The exhibit lasted for 10 days and is considered the beginning of a movement in modern and contemporary art. It has been gaining recognition throughout the African continent and globally ever since.

Marrakech has emerged as the "art capital" of Morocco. It houses numerous art museums including the Farid Belkahia Museum, named after one of the leading Jemaa el-Fna artists who died in 2014. Marrakech is home to the Yves Saint Laurent Museum and hosts the annual Marrakech International Film Festival.

Tangier is another center for art, producing renowned artists like Ahmed Yacoubi and Abdellatif Zine and Mohamed Hamri whose works are displayed around the world.

Cuisine

Moroccan cuisine is generally a mix of Arab, Andalusi,[50] Berber and Mediterranean cuisines with slight European and sub-Saharan influences. Berbers had food staples such as figs, olives and dates and prepared lamb and poultry dishes frequently. This has heavily influenced Moroccan cuisine as all of these are used in abundance. Morocco is known for dishes such as couscous, tajine, and pastilla. Moroccan cuisine uses many herbs, including cilantro, parsley, and mint; spices such as cinnamon, turmeric, ginger, cumin, and saffron; and produce such as tomatoes, onions, garlic, zucchini, bell peppers, and eggplant. One of the defining features of Moroccan cuisine is the interplay between sweet and savory flavors, as exemplified by tfaya, a mix of caramelized onions, butter, cinnamon, sugar, and raisins often served with meat.[51]

Historically, couscous has been the staple of the Moroccan diet. On special occasions, more complex meals like the traditional Moroccan pastilla and some special pastries such as gazelle ankles and briwates are served for guests.[52] Mint tea, called atay in Morocco, is commonly regarded as the national beverages. Coffee is also universally enjoyed from espresso to cappuccinos.

Celebrations and holidays

Islamic holidays

Morocco' official religion is Islam. The rhythm of life for Moroccans is dictated by religious celebrations throughout the year, such as Ramadan and Eid Al Adha. During these celebrations, most of them being public holidays, Moroccans focus on praying and spending time with their family. Moroccans also celebrate al-Mawlid al-Nabawi, the birthday of Muhammad, and the Islamic New Year.

Other religious celebrations include the Friday weekly prayer where most Moroccans go to the mosque for the Friday mid-day prayer.[53]

Jewish holidays

Morocco has long had a significant Jewish population, distinguished by traditions particular to Moroccan Jews. For example, Mimouna is a characteristically Maghrebi holiday celebrated the day after Passover.[54] Mahia is traditionally associated with Moroccan Purim celebrations.[55]

Folk celebrations

Yennayer, the Amazigh new year, has been celebrated from January 12 to January 13, the beginning of the Julian calendar, since antiquity.[56]

Other celebrations include Ashura, the tenth day of the Islamic year, and Bujlood, a folk carnival celebrated after Eid al-Adha.

Festivals

Taburida, or mawsam or fantasia, is a traditional exhibition of horsemanship in the Maghreb performed during cultural festivals and for Maghrebi wedding celebrations.[57] There are also several annual festivals that take place in Morocco, such as the Betrothal Festival in Imilshil, the rose festival in Qalaat Megouna, or the saffron festival in Taliween.

Carpets, dress and jewellery

Carpet weaving

Carpet weaving is a traditional craft in Morocco. Styles vary dramatically from region to region and from tribe to tribe. Among the more popular varieties there are:

- Azilal, High Atlas[58]

- Bujad, near Khenifra[58]

- Beni Warain, Middle Atlas[58]

- Beni M'guild, Middle Atlas[58]

- Bousherwiit[58]

- Kilim[58]

- Marmusha[59]

- Zanafi[59]

- Zemmour[59]

Some Atlas tribes, such as the Beni Ouarain, also weave hendiras, which are ornate woven cloaks for use in the winter. When it is snowing, they can be overturned and the loose loops of wool help snow fall off to keep the cloak dry.[59]

Traditional clothing

.jpg.webp)

The traditional dress for men and women[60] is called djellaba (جلابة); a long, loose, hooded garment with full sleeves. The djellaba has a hood that comes to a point called a qob. The qob protects the wearer from the sun or in colder climates, like the mountains, the qob keeps in body heat and protects the face from falling snow. For special occasions, men also wear a red cap called a bernousse, more commonly referred to as a Fez. Women wear kaftans (قفطان) decorated with ornaments. Nearly all men, and most women, wear balgha (بلغة) —- soft leather slippers with no heel, often dyed yellow. Women also wear high-heeled sandals, often with silver or gold tinsel.

The distinction between a djellaba and a kaftan is the hood on the djellaba, which a kaftan lacks. Most women's djellabas are brightly colored and have ornate patterns, stitching, or beading, while men's djellabas are usually plainer and colored neutrally.

Berber jewellery

Among other cultural and artistic traditions, jewellery of the Berber cultures worn by Berber women and made of silver, beads and other applications was a common trait of Berber identities in large areas of the Maghreb up to the second half of the 20th century.[61]

Media

Cinema

In the first half of the 20th century, Casablanca had many movie theaters, such as Cinema Rialto, Cinema Lynx and Cinema Vox—the largest in Africa at the time it was built.[62][63][64]

The 1942 American film Casablanca is supposedly set in Casablanca and has had a lasting impact on the city's image, though it was filmed entirely in California and doesn't feature a single Moroccan character with a speaking role.[65] Salut Casa! was a propaganda film brandishing France's purported colonial triumph in its civilizing mission in the city.[66]

Mostafa Derkaoui's 1973 film About Some Meaningless Events (Arabic: أحداث بلا دلالة) was screened twice in Morocco before it was banned under Hassan II.[67]

Love in Casablanca (1991), starring Abdelkarim Derqaoui and Muna Fettou, was one of the first Moroccan films to deal with Morocco's complex realities and depict life in Casablanca with verisimilitude. Bouchra Ijork's 2007 made-for-TV film Bitter Orange achieved wide support among Moroccan viewers.[68] Nour-Eddine Lakhmari's Casanegra (2008) depicts the harsh realities of Casablanca's working classes.[69][70] The films Ali Zaoua (2000), Horses of God (2012), Much Loved (2015), and Ghazzia (2017) of Nabil Ayouch—a French director of Moroccan heritage—deal with street crime, terrorism, and social issues in Casablanca, respectively.[71] The events in Meryem Benm'Barek-Aloïsi's 2018 film Sofia revolve around an illegitimate pregnancy in Casablanca.[72] Hicham Lasri and Said Naciri also from Casablanca.

Atlas Studios in Warzazat is a large movie studio.[73]

Movies in Morocco

- 1944: Establishment of the "Moroccan Cinematographic Center" (CCM/the governing body). Studios were open in Rabat.

- 1958: Mohammed Ousfour creates the first Moroccan movie "Le fils maudit".

- 1982: The first national festival of cinema – Rabat.

- 1968: The first Mediterranean Film Festival was held in Tangier. The Mediterranean Film Festival in its new version is held in Tetouan.

- 2001: The first International Film Festival of Marrakech was held in Marrakech.

Some directors have set films in Morocco. In 1952 Orson Welles chose Essaouira as the setting for several scenes in his adaptation of Shakespeare's "Othello", which had won the Grand Prix du Festival International du Film at that year's Cannes Film Festival. In 1955, Alfred Hitchcock directed The Man Who Knew Too Much and in 1962, David Lean shot the Tafas Massacre scene of Lawrence of Arabia in the city of "Ouarzazate", which houses Atlas Studios. Aït Benhaddou has been the setting of many films. The film Hideous Kinky was filmed in Marrakech.

Architecture

Qsur

.jpg.webp)

A qsar (Arabic: قصر), (p. qsur) is a North African fortified village.[74] There are over 300 qsur and qasbas the Draa Valley, particularly in the area between Agdz and Zagora.[74]

Agadirs

An agadir, not to be confused with the city Agadir, is a communal granary traditionally found in Shilha communities in southern Morocco.[75][76]

Gardens

Andalusi gardens, inherited from Morisco refugees who settled in Morocco, are a prominent feature of Moroccan architecture.[77] These have been used in building palaces such as the Bahia Palace in Marrakesh. The Andalusi garden, which usually features a burbling fountain, has an important role in cooling riads: the evaporation of water is an endothermic chemical reaction, which absorbs heat from the area garden and surrounding rooms.

Morocco has many beautiful gardens, including the Majorelle Garden in Marrakech and the Andalusian Garden in the Kasbah of the Udayas in Rabat.

Domestic architecture

Dar (Arabic: دار), the name given to one of the most common types of domestic structures in Morocco, is a home found in a medina, or walled urban area of a city. Most Moroccan homes traditionally adhere to the Dar al-Islam, a series of tenets on Islamic domestic life.[78] Dar exteriors are typically devoid of ornamentation and windows, except occasional small openings in secondary quarters, such as stairways and service areas. These piercings provide light and ventilation.[79] Dars are typically composed of thick, high walls that protect inhabitants from thievery, animals, and other such hazards; however, they have a much more symbolic value from an Arabic perspective. In this culture the exterior represents a place of work, while the interior represents a place of refuge.[80] Thus, Moroccan interiors are often very lavish in decoration and craft.

Consistent with most Islamic architecture, dars are based around small open-air patios, surrounded by very tall thick walls, to block direct light and minimize heat.[79] Intermediary triple-arched porticos lead to usually two to four symmetrically located rooms. These rooms have to be long and narrow, creating very vertical spaces, because the regional resources and construction technology typically only allow for joists that are usually less than thirteen feet.[79]

Upon entering a dar, guests move through a zigzagging passageway that hides the central courtyard. The passageway opens to a staircase leading to an upstairs reception area called a dormiria, which often is the most lavish room in the home adorned with decorative tilework, painted furniture, and piles of embroidered pillows and Moroccan rugs. More affluent families also have greenhouses and a second dormiria, accessible from a street-level staircase. Service quarters and stairways were always at the corners of the structures.[79]

Ziliij

Ziliij (Arabic: الزليج), colorful geometric mosaic tile work, is a decorative art and architectural element commonly found in Moroccan mosques, mausolea, homes, and palaces. These probably evolved from Greco-Roman mosaics, which have been found in cities such as Volubilis and Lixus.[81]

Modernist architecture

In the mid to late 20th century, architects such as Elie Azagury, Jean-François Zevaco, Abdeslam Faraoui, Patrice de Mazières, and Mourad Ben Embarek marked the architecture of Casablanca and other parts of Morocco with significant works of modernist and brutalist architecture.[82]

See also

References

- "Morocco: a rich blend of cultures". The Times & The Sunday Times. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- Travel, D. K. (2017-02-01). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Morocco. Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 978-0-241-30469-3.

- Kaʻʻāk, ʻUthmān; عثمان, كعاك، (1958). محاضرات في مراكز الثقافة في المغرب من القرن السادس عشر الى القرن التاسع عشر (in Arabic). Arab Research and Studies Institute.

- "Culture | Morocco Embassy". Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- مقلد, غنيمي، عبد الفتاح; Ghunaymī, ʻAbd al-Fattāḥ Miqlad (1994). موسوعة تاريخ المغرب العربي (in Arabic). مكتبة مدبولي،.

كما أن سيطرة المرابطين على الاندلس قد كانت سببا في ظهور حضارة مغربية أندلسية حيث اختلطت المؤثرات الاندلسية بالمؤثرات المغربية وساعد ذلك على تقدم الفن والثقافة والحضارة والعلوم في المغرب .

- Cantor, Norman F (1995), The Civilization of the Middle Ages, p. 51f

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 08 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 410, 411.

- "Evolution: Themes and actions – Dynamique Du Langage". 2013-10-04. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- Blench, Roger. "Reconciling archaeological and linguistic evidence for Berber prehistory".

- Benramdane, Farid (1998-12-31). "" Le maghribi, langue trois fois millénaire » de ELIMAM, Abdou (Ed. ANEP, Alger 1997)". Insaniyat / إنسانيات. Revue algérienne d'anthropologie et de sciences sociales (in French) (6): 129–130. doi:10.4000/insaniyat.12102. ISSN 1111-2050. S2CID 161182954.

- Merrils, A.H (2004). Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on late Antique North Africa. Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-4145-7.

- "RGPH 2014". rgphentableaux.hcp.ma. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- Yassir, Malahakch (January 2016). "Diglossic Situations in Morocco: Extended diglossia as a sociolinguistic situation in Er-rich". Academia.

- عصِيد: باحثُو الإحصاء يطرحون "سؤال الأمازيغيَّة" بطرق ملتويَة. Hespress هسبريس (in Arabic). 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- "دستور المملكة المغربية". Cour Constitutionnelle | المحكمة الدستورية (in Arabic). Retrieved 2019-10-20.

تظل العربية اللغة الرسمية للدولة. وتعمل الدولة على حمايتهاوتطويرها، وتنمية استعمالها. تعد الأمازيغية أيضا لغة رسمية للدولة، باعتبارها رصيدا مشتركا لجميع المغاربة بدون استثناء.

- Ricento, Thomas (2015). Language Policy and Political Economy: English in a Global Context. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-936339-1.

- Maaroufi, Youssef. "Recensement général de la population et de l'habitat 2004". Site institutionnel du Haut-Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc (in French). Archived from the original on 2011-07-05. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- Messaoudi, Leila, ed. (2013). Dynamique langagière au Maroc. Vol. 143. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. ISBN 978-2-7351-1425-2. OCLC 865506907.

- "Morocco: Code switching and its social functions". Morocco World News. 2014-02-12. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- Rouchdy, Aleya. (2012). Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic. Taylor and Francis. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-136-12218-7. OCLC 823389417.

- Ennaji, Moha (2005-12-05). Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-387-23980-4.

- "Morocco 2011 Constitution - Constitute". constituteproject.org. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- Boukous, Ahmed (1995). "La langue berbère: maintien et changement". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 112: 9–28. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1995.112.9. ISSN 1613-3668.

- Roettger, Timo B. (2017). Tonal placement in Tashlhiyt: How an intonation system accommodates to adverse phonological environments. Language Science Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-3-944675-99-2.

- mlynxqualey (2020-04-29). "180+ Books: A Look at Moroccan Literature Available in English". ARABLIT & ARABLIT QUARTERLY. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- Parrilla, Gonzalo Fernández; Calderwood, Eric (2021-04-16). "What Is Moroccan Literature? History of an Object in Motion". Journal of Arabic Literature. 52 (1–2): 97–123. doi:10.1163/1570064x-12341421. ISSN 0085-2376. S2CID 235516663.

- "مالكة العاصمي: أنواع الأدب الشعبي بالمغرب – طرب الآلة – – وزارة الثقافة". 2021-10-08. Archived from the original on 2021-10-08. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- Dossier I, Musiques d'Algérie Dossier II, Algérie: histoire, société, cultures, arts. Vol. 47. Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Mirail. 2002. ISBN 2-85816-657-9. OCLC 496273089.

- "طرب الآلة.. ذلك الفن الباذخ". مغرس. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- "كيف صارت "شمس العشية" أغنية العيد في المغرب؟". BBC News Arabic (in Arabic). 2020-05-25. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- Sells, Professor Michael A. (2000-08-31). The Literature of Al-Andalus. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-521-47159-6.

- Ahmed Aydoun (2001–2002). "Anthologie de la Musique Marocaine". Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- "Discover Islamic Art Virtual Exhibitions | The Muslim West | Andalusian-Maghrebi Art |". Islamic Art Museum. 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Brigitte Hintzen-Bohlen (2000). Andalusia: Art & Architecture. Könemann. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-3-8290-2657-4.

- Kane, Ousmane (2016-06-07). Beyond Timbuktu: An Intellectual History of Muslim West Africa. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05082-2.

- Habibeh Rahim (1996). Inscription as Art in the World of Islam: Unity in Diversity: at the Emily Lowe Gallery, April 14 – May 24, 1996. Hofstra Museum, Hofstra University. p. 65.

- "محمد بن علي الرباطي .. أول رسام على الطريقة الأوروبية". مغرس. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- Irbouh, Hamid (2005). Art in the Service of Colonialism. I.B.Tauris. doi:10.5040/9780755607495. ISBN 978-1-85043-851-9.

- "Give us a swirl: How Mohamed Melehi became Morocco's modernist master". The Guardian. 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- Katarzyna Pieprzak (1 January 2010). Imagined Museums: Art and Modernity in Postcolonial Morocco. U of Minnesota Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4529-1520-3.

- "R22 Art Radio / Radio Apartment 22 راديو الشقة ٢٢ - L'appartement 22". appartement22.com. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Bérénice Saliou. . Contemporary Art Magazine, Issue 6

- "Tbourida" (PDF).

- "Surveillé(e)s" (PDF). L'appartement 22. 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Geraldine Pratt (23 June 2014). Film and Urban Space. Edinburgh University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7486-7814-3.

- Julia Barroso Villar (2 December 2016). Mujeres árabes en las artes visuales. Los países mediterráneos. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. p. 176. ISBN 978-84-16933-22-8.

- Alice Planel. Traveling Back to Ourselves: The Maghreb as an Art Destination, p. 4, higheratlas.org.

- Jaggi, Maya (2019-08-03). "Casablanca's Gift to Marrakech and the Birth of Morocco's Modern Art Movement". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Leu, Felix (2017). Berber tattooing in Morocco's Middle Atlas: tales of unexpected encounters in 1988. Kenmare, County Kerry, Ireland: SeedPress. ISBN 978-0-9551109-5-5. OCLC 1023521225.

- Yabiladi.com. "Moroccan cuisine, a melting pot of peoples and cultures [Interview]". en.yabiladi.com. Retrieved 2021-03-03.

- Nada Kiffa (27 October 2017). "T'faya in Moroccan Cooking". Taste of Maroc. Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Moroccan Traditional Cuisine | What to Eat in Morocco | MoroccanZest". Moroccan Zest. 2018-07-28. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- "Morocco Culture & Religion | MoroccanZest". Moroccan Zest. 2018-08-20. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- Jane S. Gerber (1995). "Integrating the Sephardic Experience into Teaching". In Jane S. Gerber; Michel Abitbol (eds.). Sephardic Studies in the University. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8386-3542-1.

- "Sous le figuier, l'alcool !". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 2020-03-17.

- Boudraa, Nabil. "Far From North Africa, Berbers In The U.S. Ring In A New Year". NPR. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- Steet, Linda (2000). Veils and Daggers: A Century of National Geographic's Representation of the Arab World. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 141.

- "Our guide to different types of Moroccan Rugs". A New Tribe. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- "THE VIEW FROM FEZ: Beginners' Guide to Moroccan Carpets". THE VIEW FROM FEZ. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- "Traditional Clothing | Kaftan and Djellaba | Morocco Guide".

- See, for example, Rabaté, Marie-Rose (2015). Les bijoux du Maroc: du Haut-Atlas à la vallée du Draa. Paris: ACR ed. and Rabaté, Marie-Rose; Jacques Rabaté; Dominique Champault (1996). Bijoux du Maroc: du Haut Atlas à la vallée du Draa. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud/Le Fennec, as well as Gargouri-Sethom, Samira (1986). Le bijou traditionnel en Tunisie: femmes parées, femmes enchaînées. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud.

- "LES CINÉMAS DE L'EPOQUE A CASABLANCA.6/6". Centerblog (in French). 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- "Cinéma: 245 salles fermées entre 1980 et 2017". La Vie éco (in French). 2019-02-16. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- Pennell, C. R. (2000). Morocco Since 1830: A History. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-426-1.

- "When Tangier Was Casablanca: Rick's Café & Dean's Bar". Tangier American Legation. 2011-10-21. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- Von Osten, Marion; Müller, Andreas. "Contact Zones". Pages. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- ""أحداث بلا دلالة".. إعادة النبش في تحديات السينما المغربية بعد نصف قرن". الجزيرة الوثائقية (in Arabic). 2020-12-28. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- "جدير بالمشاهدة: "البرتقالة المرة".. فيلم ذاق عبره المغاربة مرارة الحب (فيديو وصور)". al3omk.com (in Arabic). Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- "" Casa Negra " remporte la médaille de bronze". aujourdhui.ma. Aujourd'hui le Maroc. 9 November 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Karim Boukhari (12 December 2008). "Nari, nari, Casanegra". telquel-online.com. TelQuel. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- Goodman, Sarah (2019-03-17). "Behind the Silver Screen: A Conversation with Morocco's Nabil Ayouch". Morocco World News. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- "" Sofia ": le récit d'un délit de grossesse au Maroc" (in French). 2019-08-24. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- "Destination Ouarzazate, entre culture hollywoodienne et artisanat berbère". journaldesfemmes.fr (in French). Retrieved 2020-03-17.

- Pradines, Stéphane (2018-09-17). Earthen Architecture in Muslim Cultures: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-35633-7.

- "Greniers collectifs – Patrimoine de l'Anti Atlas au Maroc | Holidway Maroc". Holidway (in French). 2017-02-28. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- "Collective Granaries, Morocco". Global Heritage Fund. 12 May 2018. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- "الحدائق الأندلسية بالمغرب .. "جنان" من التاريخ". Hespress (in Arabic). 16 June 2013. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- Verner, p. 9

- Verner, pp. 41–42

- Verner, pp. 9–10

- Lesch-Middelton, Forrest (2019-10-01). Handmade Tile: Design, Create, and Install Custom Tiles. Quarry Books. ISBN 978-0-7603-6430-7.

- Dahmani, Iman; El moumni, Lahbib; Meslil, El mahdi (2019). Modern Casablanca Map. Translated by Borim, Ian. Casablanca: MAMMA Group. ISBN 978-9920-9339-0-2.

Bibliography

- Verner, Corince. (2004). The villas and riads of Morocco. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers

External links

- TRC Needles entry on Moroccan embroidery

- Traditional Moroccan music from Morocco's Ministry of Communication

- The Moroccan Souk