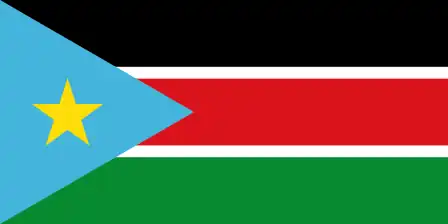

Culture of South Sudan

The culture of South Sudan encompasses the religions, languages, ethnic groups, foods, and other traditions of peoples of the modern state of South Sudan, as well as of the inhabitants of the historical regions of southern Sudan.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of South Sudan |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Languages

The official language of South Sudan is English.[1]

There are over 60 indigenous languages, most classified under the Nilo-Saharan Language family. Collectively, they represent two of the first order divisions of Nile Sudanic and Central Sudanic.

In the border region between Western Bahr Al Ghazal state and Sudan are an indeterminate number of people from West African countries who settled here on their way back from Mecca—who have assumed a traditionally nomadic life—that reside either seasonally or permanently. They primarily speak Chadian languages and their traditional territories are in the southern portions of the Sudanese regions of Northern Kordofan and Darfur.

In the capital Juba, there are several thousand people who use dialect forms of Arabic, usually called Juba Arabic, but South Sudan's ambassador to Kenya said on 2 August 2011 that Swahili will be introduced in South Sudan with the goal of supplanting Arabic as a lingua franca, in keeping with the country's intention of orientation toward the East African Community, rather than toward Sudan and the Arab League.[2]

Religion

While the northern parts of Sudan have been predominantly Muslim, South Sudan is predominantly Christian or African traditional animist, and a small number of citizens are Muslims.[3]

National holidays

2017 Public holidays[4]

- January 1, New Year's Day

- January 9, Peace Agreement Day

- April 1, Easter Day

- May 1, May Day

- May 16, SPLA Day

- June 15, Eid al-Fitr

- July 9, Independence Day

- July 30, Martyrs Day

- August 11, Eid al-Adha

- December 25, Christmas Day

- December 28, Republic Days

- December 31, New Year's Eve

Ethnic groups

Ethnic groups in South Sudan include the Nuer, Dinka, Shilluk, Murle, Dongotono, Anuak, Atuot, Burun, Jur Beli, Moru, Pojulu, Otuho, Thuri, Jur Chol or Luwo, Didinga, Avukaya, Mundu, Ketebo, Balanda, Morokodo, Ndogo, Acholi, Lulubo, Lokoya, Kichepo, Baka, Lango, Lopit, Nyangwara, Tennet, Jur Mananger, Kuku, Boya, Lugbara and Sere, among others.[5]

Between 1926 and 1936, the British anthropologist E.E. Evans-Pritchard, the author of several books on culture and lifestyles in southern Sudan,[6] also took thousands of photographs during his anthropological fieldwork. About 2500 of his images, mainly showing the life of the Azande, Moro, Ingessana, Nuer and Bongo peoples are in the collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum, the University of Oxford's museum of anthropology, with many of them published online.[7]

Further, the Pitt Rivers Museum's webpage offers a detailed catalogue of the museum's collections from southern Sudan. These collections comprise more than 1300 artefacts and 5000 photographs. Both the artefacts and photographs serve as a research tool for studying the cultural and visual history of southern Sudan. The site also "provides a map; annotated lists of cultural groups, collectors, photographers, and people portrayed in the photographs; and a set of further resources (relevant literature, websites, and a site bibliography)."[8]

Society

Most South Sudanese keep up the core of their local culture, even while in exile or diaspora. Traditional culture is highly upheld and a great focus is given to knowing one's ethnic origins and language. Although the common languages spoken are Juba Arabic and English, there are plans to introduce Kiswahili to the population to improve the country's relations with its East African neighbors.

Music

South Sudan has a rich tradition of folk music that reflects its diverse indigenous cultures. For example, the folk music of the Dinka people include highly appreciated poetry, while the Azande are especially known for their storytelling. The drummers of the record Wayo[9] combine spiritual chanting with interlocking grooves. The mesmerizing music, centered around the kpaningbo, a large wooden xylophone played by three people, is completed by the rest of the village, who rotate through a series of bells and percussive instruments.

Due to geographic location and the many years of civil war, the musical culture is heavily influenced by the countries neighboring South Sudan. Many South Sudanese fled to Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda, where they interacted with the nationals and learned their languages and culture. Many of those who remained in the country, while it was still part of Sudan, or went North to live in Sudan or Egypt, assimilated the Arabic culture and language of their neighbors.

Many music artists from South Sudan use English, Kiswahili, Juba Arabic, their local language, or a mix of languages. During the 1970s and 1980s, Juba was home to a thriving nightlife. Top local bands included the Skylarks and Rejaf Jazz. Popular artist Emmanuel Kembe sings folk, reggae, and Afrobeat. Yaba Angelosi, who emigrated to the United States in 2000, sings Afrobeat, R&B and Zouk. Dynamiq is popular for his reggae releases, and Emmanuel Jal is a hip hop artist of international fame. - There are also a few female artists that South Sudan has produced so far.

Literature

Apart from traditional oral literature of its different ethnic groups, there are modern literary writers of South Sudan, such as the short story writer Stella Gaitano, who writes in Arabic since her beginnings as a student at the University of Khartoum.[10]

Taban Lo Liyong, who was born in southern Sudan in 1939 and studied in the United States during the 1960s, is one of Africa's well-known poets and writers of fiction and literary criticism.

Alephonsion Deng and his brother Benson Deng have become known as refugees, who first fled from war and starvation to neighboring Kenya, and later emigrated to the United States. There, they co-wrote their account as the Lost Boys of Sudan.[11]

Sport

- South Sudanese Wrestling is the most popular traditional sport across all the three regions. It brings thousands of people together occasionally.

- South Sudan Football Association

- South Sudan national football team

- South Sudan national basketball team

See also

References

- "The Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan, 2011". Government of South Sudan. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011. Part One, 6(2). "English shall be the official working language in the Republic of South Sudan".

- "South Sudanese still in Kenya despite new state". Xinhua. 2 August 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- "SustainabiliTank: The animist culture of South Sudan (Juba) clashed with Islamic North and the Divide & Rule Brits. Now they prepare for a January 2011 vote for Independence and the first break-away African State will be born. Many more should be allowed to follow. But this particular case is specifically hard as most people are still centuries behind. About 65% of the people are Christians. 32.9% believe in the traditional African religion. About 6.2% are Islam. The last 0.4% believe in another Religion". Sustainabilitank.info. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "Holidays in South Sudan in 2017". TimeAndDate.com. 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Mary Douglas (1981). Edward Evans-Pritchard. Kingsport: Penguin Books.

- "Biography information for Pritchard at the Southern Sudan Project". southernsudan.prm.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- "Southern Sudan Photo and Object Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum". southernsudan.prm.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Network, World Music. "Trance Percussion Masters of South Sudan". World Music Network. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Kushkush, Isma’il (25 December 2015). "Telling South Sudan's Tales in a Language Not Its Own". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "'Lost Boys of Sudan' Finally Find a Home". NPR.org. Retrieved 20 June 2020.