Model (art)

An art model poses, often nude, for visual artists as part of the creative process, providing a reference for the human body in a work of art. As an occupation, modeling requires the often strenuous 'physical work' of holding poses for the required length of time, the 'aesthetic work' of performing a variety of interesting poses, and the 'emotional work' of maintaining a socially ambiguous role. While the role of nude models is well-established as a necessary part of artistic practice, public nudity remains transgressive, and models may be vulnerable to stigmatization or exploitation.[1]: 1 Artists may also have family and friends pose for them, in particular for works with costumed figures.

Much of the public perception of art models and their role in the production of artworks is based upon mythology, the conflation of art modeling with fashion modeling or erotic performances, and representations of art models in popular media.[2]: 15–18 One of the perennial tropes is that in addition to providing a subject for an artwork, models may be thought of as muses, or sources of inspiration without whom the art would not exist.[3]: 68–79, 102–115 Another popular narrative is the female model as a male artist's mistress, some of whom become wives.[4]: 3 None of these public perceptions include the professional model's own experience of modelling as work,[4]: 44–45 the performance of which has little to do with sexuality.[4]: Ch. 10

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_130_x_88.8_cm%252C_Mus%C3%A9e_Picasso%252C_Paris%252C_France.jpg.webp)

Beginning with the Renaissance, drawing the human figure has been considered the most effective way to develop the skills of drawing. In the modern era it became established that it is best to draw from life, rather than from plaster casts or copying two dimensional images such as photographs.[5] In addition, an artist has an emotional[6]: 32 or empathic[7]: 4 connection to drawing another human being that cannot exist with any other subject. What is called the life class became an essential part of the curriculum at art colleges. In the classroom setting, where the purpose is to learn how to draw or paint the human form in all the different shapes, ages and ethnicity, anyone who can hold a pose may be a model.

Role of the model

Although artists may also rely on friends and family to pose, art models are most often paid professionals with skill and experience. Rarely employed full-time, they must be gig workers or independent contractors if modeling is to be a major source of income. Paid art models are usually anonymous and unacknowledged subjects of the work.[8] Models are most frequently employed by art schools or by informal groups of artists that gather to share the expense of a model. Models are also employed privately by professional artists. Although commercial motives dominate over aesthetics in illustration, its artwork commonly employs models. For example, Norman Rockwell employed his friends and neighbors as models for both his commercial and fine art work.[9]

In the second half of the 20th century, the dominance of abstraction in the art world reduced the need for models by professional artists except for the remaining figurative artists. However, in art schools drawing from life remained part of the training needed for a complete visual arts education.[4]: 8–9 In recent years, art modeling has expanded from educational settings to non-traditional art spaces and sometimes bars, blurring the line between art and entertainment.[1]: 9 With the increasing presence of sexual imagery in popular culture, effort is required to maintain the desexualized context of nude modeling in studio classes.[1]: 21–22

Training and selection

In some countries there are figure model guilds that concern themselves with the competence, conduct and reliability of their members. An example is the Register of Artists' Models (RAM) in the United Kingdom. Some basic training is offered to beginners and membership is by audition – to test competence, not to discriminate on grounds of physical characteristics. RAM also acts as an important employment exchange for models and publishes the 'RAM Guidelines', which are widely referred to by models and employers.[10] A similar organization in the United States, the Bay Area Models Guild in California, was founded in 1946 by Florence Wysinger Allen.[11] Groups also exist in Australia[12] and Sweden.[13] These groups may also attempt to establish minimum rates of pay and working conditions, but only rarely have models been sufficiently organized to go on strike.[14][15][16]

Appearance/age/gender

Unlike commercial modeling, modeling in an art school classroom is for the purpose of teaching students of art how to draw humans of all physical types, genders, ages, and ethnicity.[17]: 11, 77, 81

Children are generally excluded from modeling nude for classes. The minimum age can vary, but is often 15 to 18. Despite being nonsexual in nature, this may be influenced by the age of consent (i.e. at or slightly below). Younger children are not good candidates for art modeling since they lack the ability to hold still.[4]: 9

Sally Mann published the book Immediate Family, in which 13 of the 65 images are of her children nude.[18] Mary Gordon characterized many of these images as sexualizing children regardless of artistic merit.[19] Mann's response to this criticism has been that the images were spontaneous and natural, having no sexual connotations other than those supplied by the viewer.[20] Less well-known photographers have been charged, but not convicted, for suspected child abuse for similar photographs of their own children.[21] Jock Sturges photographed entire families of naturists[22] which led to an FBI investigation when a photo lab employee reported the images, however, no charges were made.[23]

_01.jpg.webp)

Gender roles and stereotypes in society are reflected in different experiences for male and female art models, and different responses when those not in the arts learn that someone is a nude model. However, both male and female models tend to keep their modeling careers distinct from their other social interactions, if for different reasons. Attitudes toward male nudity, issues of homosexuality when male artists work with male models, and some bias in favor of the female form in art may lead to less opportunity for male models.[4] Works of art that include male nudity are much less marketable.[24] However, historically this has not been the case (See below).

Working as a model

Posing nude is physically and emotionally challenging, but models find the effort worthwhile and appreciate having a role in the creative arts.[25][26]

Physical work

While posing, a model is expected to remain essentially motionless, and return to the same pose after a break.[17]: 47–55 [4]: 111–113 While posing for a class models do not talk, and should not be spoken to by students, maintaining the serious atmosphere of the studio.[4]: 64–67 Poses can range in length from seconds to many hours—with appropriate breaks—but the shortest is usually one minute. Short dynamic poses are used for gesture drawing exercises or warm-ups, with the model taking strenuous or precarious positions that could not be sustained for a longer pose. Sessions proceed through groups of poses increasing in duration. Active, gestural, or challenging standing poses are often scheduled at the beginning of a session when the models' energy level is highest. Specific exercises or lesson plans may require a particular type of pose, but more often the model is expected to do a series of poses with little direction. The more a model knows about the types of exercises used to teach art, the better they become at posing.[24] Occasionally a pose will cause unexpected problems, such as constricting blood flow that could result in a model passing out.[27] While the first time posing may cause anxiety, most continue due to the relatively high pay. The most significant characteristic of the job mentioned by models is the physical exertion required.[28]

Poses fall into three basic categories: standing, seated and reclining. Within each of these, there are varying levels of difficulty, so one kind is not always easier than another. Artists and life drawing instructors will often prefer poses in which the body is being exerted, for a more dynamic and aesthetically interesting subject. Common poses such as standing twists, slouched seated poses and especially the classical contrapposto are difficult to sustain accurately for any amount of time, although it is often surprising what a skilled model can do. The model's level of experience and skill may be taken into account in determining the length of the posing session and the difficulty of the poses.

Models usually poses on a raised platform called the model stand or dais. When artists are working standing at easels, a model stand is essential to avoid a distorted perspective. If the model is posed standing on the floor, the artist should draw while seated.[7]: 14–15 In sculpture studios this platform may be built to rotate periodically through the session to allow for a 360° view for every artist.[29] Long poses are generally required for painting (hours) and sculpture (perhaps days). To aid in resuming a long pose after a break, chalk marks and/or masking tape are often placed on the model stand.

Aesthetic work

The most creative aspect of modeling is being able to think of an endless variety of new and interesting poses. One typical short-pose session may require five two-minute gestures, followed by two 5, two 10, and five 25 minute poses separated by five-minute breaks.[24]: 42 When modeling for the same group, new poses are expected at each session. Most models learn on the job, but many have experience in the performing arts, athletics, or yoga that provide a basis for posing, such as strength, flexibility, and a well-developed sense of body position.[17] Those that try modeling on a whim and find it to be a rewarding experience then seek to learn more about the job. Some may have previously taken an art class and seen other models, but others rely upon fine art museums and books for suggestions on how to pose.[4]: 103–104

Experienced models work for many employers, gaining a wider knowledge of methods and practices than most individual artists or art teachers. Many models are visual artists themselves, and come to think of modeling as part of their visual arts practice, or as a creative activity in its own right.[2]: 36

Emotional work

In social science terms, participants in the art world where the art model is recognized as having a valuable role are a sub-culture, with norms of behavior and a definition of the situation that ideally support models' being proud of their work. However, stereotypes and prejudices of the larger culture may threaten these norms and definitions.[1]: 8 Pride in being a model comes from identification with fine arts education and creativity as having social value, and is dependent on the quality of teaching, which models experience first-hand in a myriad of settings.[2]: 37

Sexuality is an issue in an art studio where naked models are present, and has become more so with the sexualization of the body in contemporary cultures. The traditional definition of the situation in art studios has been that the nudity of models is understood as functional, not sexual. The norms and behaviors the support this understanding included models being naked only while posing, quickly disrobing/robing and not interacting with others while naked. This understanding is less strict when student artists are also models, either in classes or posing for each other outside of class. The other aspect of sex in the arts is gender, including feminism critiques of the performance of gender in the classroom and representations of gender in figurative works.[2]: 127–131

A common experience for young first-time participants in a figure class, both models and students, is overcoming anxiety for the initial session due to preconceptions regarding public nudity.[30][31] Occasionally the class is the first time a student has seen someone of the opposite sex entirely nude in real life, but they quickly get used to it.[28]

Types of modeling

Models for art classes usually pose nude, though visually non-obstructive personal items such as small jewelry and eyeglasses may be worn. In a job advertisement seeking nude models, this may be referred to as being "undraped" or "disrobed." Art models who pose in the nude for life drawing are also called life models or figure models.

Academic modeling

Job descriptions posted by art schools list requirements that are generally limited to being able to hold poses up to 20 to 45 minutes (depending on the institution), and to follow cues from the instructor.[32][33]

At many public universities in the United States, including the City University of New York,[34] the University of Alaska,[35] the University of California,[36] the University of Utah,[37] Western Oregon University[38] and Western Washington University[39] Art Model is listed in the human resources system as would any part-time temporary job for students seeking financial aid. It is similar at Indiana University, however, current students at the Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design may not pose nude, but only clothed, while students in other departments may be nude.[40] At other institutions students cannot be models, even if they are not art students, to avoid any possibility of conflict of interest.[41][42][43]

Strict rules of conduct are observed to maintain decorum and emphasize the serious intent of figure studies.[44][45] Some schools have lists of guidelines, while others have extensive manuals that describe policies regarding both in-class and outside interaction by models, students, and faculty; with special consideration for issues of sexual harassment. The Columbus College of Art and Design guidelines specifically state that students are discouraged from forming any amorous relationship with models, and must report any existing relationship to avoid possible conflicts.

Admission to and visibility of the area where a nude model is posing is tightly controlled. Disrobing is done discreetly, and the model wears a robe when not posing.[4] Models may not be accompanied by non-class members.[46] It is generally prohibited for anyone (including the instructor) to touch a model. Very close examinations are only made with the permission of the model. Some institutions allow only the instructor to speak directly with a model. Experienced models avoid any sexually suggestive poses.[4] Art instructors and institutions may consider the incident of a male model gaining an erection while posing cause for termination, or grounds for not hiring him again.[47] Guidelines at St. Olaf College discourages students making comments on a model's appearance.[48] Photography is generally forbidden.[43]

Any of these policies may vary in different parts of the world. In Europe and South America attitudes are more relaxed than in the United States, while in China, Taiwan and Korea attitudes are more repressed.[17]: 39

Artist's groups

While otherwise similar to art school modeling, groups variously called "open studios" or "drop-in sessions" lack instruction. They may be sponsored by arts organizations or galleries; or meet in an artist's private studio or home. Generally the attendees are experienced artists who want to continue the practice of life drawing, and find an informal group easier and more economical, paying a fee for each session or a series.[24]: 18–19

In many locations there may be few opportunities for figure drawing, and also few that are willing to model. Those that do so seek an additional source of income, but also find validation in being able to hold poses and contributing to the artistic process. However, they are more likely to avoid letting it be known that they model, given the negative associations toward nudity. The Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma has been holding a weekly session for as long as anyone can remember. Otherwise a typical open session, a professor at the University of Tulsa offers instruction once each month. The models for these sessions tend to be middle age or older, and the artists are generally experienced drawing nude models with only the occasional new participant.[49]

Modeling for individual artists

In non-academic settings, models may pose as requested by artists within the limits of the law and their own comfort, including work that requires physical contact with other models, the artist, or the public. French artist Yves Klein applied paint to models' bodies which were then pressed into or dragged across canvas both as performance art and as painting technique.[50] In 2010 at the Museum of Modern Art, a retrospective of the work of Marina Abramović included two nude models, male and female, standing in a narrow doorway through which visitors passed, replicating a work performed by the artist and a partner in 1977.[51]

Models who work for individual artists in a private studio tend to observe art school norms in order to maintain the definition of modeling as serious artistic work. However, there are no longer strict rules, so a more informal working relationship may be established over time. This may include not undressing in another room, or not wearing a robe during breaks. In addition, silence is no longer necessary if the artist is comfortable working and conversing with the model. A more collegial relationship may develop where artist and model feel that they are collaborating. However, in a private studio environment, with an artist on a deadline or with commission guidelines, stricter work standards may apply regarding punctuality and holding longer, more demanding poses, but also higher rates of pay. However, private studio work is rare outside of major cities.[4]: 49–54

Chuck Close apologized in 2017 when several women accused him of making inappropriate comments when they came to his studio to pose, but initially denied any wrongdoing.[52] Following his death in 2021, it was revealed that Close suffered from a form of dementia, which could account for his behavior.[53]

Jan de Bray, The Banquet of Cleopatra, Royal Collection (1652)

Jan de Bray, The Banquet of Cleopatra, Royal Collection (1652) Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, better known as Whistler's Mother, a portrait of Anna McNeill Whistler by her son, James McNeill Whistler (1871)

Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, better known as Whistler's Mother, a portrait of Anna McNeill Whistler by her son, James McNeill Whistler (1871) The Woman with a Parasol (Suzanne Hoschedé) by Claude Monet (1886)

The Woman with a Parasol (Suzanne Hoschedé) by Claude Monet (1886) Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of the Artist's Mother, (October 1888)

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of the Artist's Mother, (October 1888) The Artist and His Family by Lovis Corinth (1909)

The Artist and His Family by Lovis Corinth (1909)

Artist Peter Graham in his studio with his mother as model (1952)

Artist Peter Graham in his studio with his mother as model (1952)

Family members, wives and life partners

Through history, artists use family members as models, both nude and otherwise, in creating their works. The Dutch Golden Age painter Jan de Bray specialized in the portrait historié, "portraits" of historical figures using contemporary figures as models, including himself and his family, as in two versions of The Banquet of Cleopatra (1652 and 1669).[54] Rose Beuret was the subject of several portrait sculptures by Auguste Rodin and his companion for 53 years, but his wife only in the final year of her life. Camille Doncieux, first wife of Claude Monet also posed for paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Édouard Manet. Hortense Fiquet, companion and later wife of Cézanne is rarely mentioned in art history.[55] Lucian Freud painted many of his 14 children, sometimes nude; the most controversial being his daughter Annie Freud in 1963 when she was 14.[56] However, she now looks back upon posing for her father as a positive experience.[57]

The relationship between male photographers and their wives as models is studied in Arthur Ollman's book, The Model Wife. It focuses on the photographers Baron Adolph de Meyer (whose wife was Olga de Meyer), Alfred Stieglitz (whose wife was Georgia O'Keeffe), Edward Weston and model Charis Wilson, Harry Callahan, Emmet Gowin, Lee Friedlander, Masahisa Fukase, Seiichi Furuya, and Nicholas Nixon.[58]

The Prodigal Son in the Tavern portrays two people identified as Rembrandt and his wife Saskia by Rembrandt van Rijn (c. 1635)

The Prodigal Son in the Tavern portrays two people identified as Rembrandt and his wife Saskia by Rembrandt van Rijn (c. 1635) The Startled Nymph (modeled by Suzanne Manet (née: Leenhoff)) by Édouard Manet (1859–1861)

The Startled Nymph (modeled by Suzanne Manet (née: Leenhoff)) by Édouard Manet (1859–1861) Marie-Hortense Fiquet Cézanne by Paul Cézanne (1877)

Marie-Hortense Fiquet Cézanne by Paul Cézanne (1877)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Paul Gauguin portrait of his young wife Tehamana, (1893)

Paul Gauguin portrait of his young wife Tehamana, (1893) Pierre Bonnards wife, Siesta (1900)

Pierre Bonnards wife, Siesta (1900)

Jeanne Hébuterne by Amedeo Modigliani (1918)

Jeanne Hébuterne by Amedeo Modigliani (1918) Alfred Stieglitz portrait of Georgia O'Keeffe, (1918)

Alfred Stieglitz portrait of Georgia O'Keeffe, (1918)

Clothed modeling

Painting classes, and artists doing historical themed works often require clothed or costumed models who take poses that may be sustained until the work is completed. This creates some demand for clothed models in those schools that continue to teach academic painting methods. Some models may promote their services based upon having interesting or varied costumes.[60] Clothing is required in public venues, such as Dr Sketchy's Anti-Art School,[61] but occurs in more traditional settings as well, such as the fund-raising marathons sponsored by the Bay Area Models Guild.[24]: 39 Other than costumes, the work requirements and conditions of clothed models for art are identical to that of nude models.

Usually an individual who is having their own portrait painted or sculpted is called a "sitter" rather than a model, when they are not being paid to pose, it is the artist who is being paid to create a likeness.[62] Modern portraits are done from photographs at least in part, although artists prefer to have at least some hours of live sitting at the beginning to better capture the personality, and at the end for final touches. In some cases, the sitter may reject a portrait as an unflattering, and destroy it.[63]

Photography

There has been controversy regarding the status of photography as a fine arts medium that is reflected in the unwillingness of some models to also pose nude for photography as they would for drawing or painting.[4]: 18–25 The experience of nude modeling for an amateur photographer is different from that of posing for figure drawing/painting.[29] Traditional media create a single image that is not a true likeness of the individual model, but photographs require a release in order to protect the model's right to privacy. The hourly rate of pay for models posing for fine art photography is much higher than for other media, although less than for commercial photography.[4]

Occasionally the distinction of participating in Fine Art may make a young amateur model willing to pose for a well-known photographer, examples being Vanessa Williams and Madonna. A signed print of one of the nude photographs of Madonna taken by Lee Friedlander in 1979 sold at auction in 2012 for $37,000.[64] Although largely a result of her fame, the model does not share in this increased value of the artwork.

Online modeling

During the COVID-19 pandemic, life drawing classes began to appear on online platforms, most frequently on Zoom. This shift to virtual spaces created new, global communities and increased access to artists who were able to join sessions from their homes.[65] Although remote sessions suffer from some difficulties, such as the flattening and distortion of the camera and the lack of direct communications, there has been an expansion of the community willing and able to participate, both as models and artists.[66][67]

Models at the Government College of Art & Craft in India for whom posing for classes is their only income do not have the online option, but have been supported by donations from artists.[68]

Nudity and body image

In recent years, a connection has been made between social issues of body image, sexualization and art modeling with some promoting wider participation in life drawing, including at a younger age, to provide an experience of real nude people as an alternative to social media representations of idealized bodies.[69] The social benefits of life drawing had been suggested by David B. Manzella in the 1970s while director of the Rhode Island School of Design. Nude models were introduced to the young people's classes with the permission of parents.[70] Models often cite acceptance of their bodies as one of the benefits of modeling.[71][72] While younger women continue to be the typical model, men and older models are welcomed in cities with an active arts community such as Glasgow, Scotland.[59] Figure On Diversity is one initiative which aims to increase representation in studio art and studio art education by creating resources in support of models who hold visible marginalized identities.[73]

Alternative views

All of the above is based upon a moderate position regarding the value of figure studies and nudity in art. There are also schools or studios that may be more conservative, or more liberal. Many art programs in Christian institutions consider nudity in any form to be in conflict with their beliefs, and therefore hire only clothed models for art classes.[74] None of the Protestant Evangelical colleges in the United States were found to include nude models in their arts and graphic design programs, citing it as an immodest practice; yet similar institutions in Australia held life drawing classes.[75] At Louisiana State University, there are rare objections to nudity by religious or conservative students, but the faculty assert that drawing the body is necessary training for art in general and to understand the structure underneath clothing. Models at LSU are full-time students who learn about modeling from other students or artists.[28] Brigham Young University does not allow nude models, describing their policy as self-censorship within the context of the school's honor code.[76]

Other institutions view the absence of figure studies as bringing into question the completeness of the art education offered.[77] Some recognize that an appreciation of the beauty of the human body is compatible with a Christian education.[78] Gordon College not only maintains the need for nude figure studies as part of a complete classical art education, but sees the use of models clad in swimwear or other revealing garments as placing the activity in the context of advertisement and sexual exploitation.[79]

James Elkins voices an alternative to classical "dispassionate" figure study by stating that the nude is never devoid of erotic meaning, and it is a fiction to pretend otherwise.[80] Even the staunch advocate of classical aesthetics Kenneth Clark recognized that "biological urges" were never absent even in the most chaste nude, nor should they be unless all life is drained from the work.[81] Most models maintain that posing nude need not be any more sexual than any other coed social situation as long as all participants maintain a mature attitude.[4] However, decorum is not always maintained when either a model or the students are not familiar with the often unspoken rules. Models may be apprehensive about posing for incoming freshmen who, having never encountered classroom nudity, respond immaturely.[17][29]

Acceptance of the erotic is apparent in the work and behavior of some artists, for example Picasso was also famous for having a series of model/muse/mistresses through his life: Marie-Thérèse Walter, Fernande Olivier, Dora Maar, and Françoise Gilot. The painter John Currin, whose work is often erotic, combines images from popular culture and references to his wife, Rachel Feinstein.

A feminist view is the male gaze, which asserts that nudes are inherently voyeuristic, with the viewer in the place of the powerful male gazing upon the passive female subject.[82]

History

The role of art models has changed through different eras as the meaning and importance of the human figure in art and society has changed.[81][83] Nude modeling, nude art and nudity in general have at times been the subject to social disapproval, at least by some elements in society.[1]: 3 When the nude in art was most popular, the models that made these artworks possible might be of low status and poorly paid. The stereotype of the female art model was part of bohemianism in the late 19th and early 20th century Europe. The combination of nakedness and the exchange of money led others to associate nude modeling with prostitution, particularly in the United States.[4]: 6–7

As the 20th century progressed, models gained more recognition and status, including forming the first organizations with some of the functions of labor unions thus becoming a professional occupation. It became possible for individuals to gain notoriety, such as Audrey Munson who was the model or inspiration for more than 15 statues in New York City in the 1910s.[84] Quentin Crisp began a thirty year career as a model in 1942.[1]: 20–21

Ancient and Post-classical

The Greeks, who had the naked body constantly before them in the exercises of the gymnasium, had far less need of professional models than the moderns; but it is scarcely likely that they could have attained the high level reached by their works without constant study from nature. It was probably in Ancient Greece that models were first used. The story told of Zeuxis by Valerius Maximus, who had five of the most beautiful virgins of the city of Crotone offered him as models for his picture of Helen, proves their occasional use. The remark of Eupompus, quoted by Pliny, who advised Lysippos, "Let nature be your model, not an artist", directing his attention to the crowd instead of to his own work, also suggests a use of models which the many portrait statues of Greek and Roman times show to have been not unknown.[85] The names of some of these models of the era are themselves known, such as the beautiful Phryne who modeled for many paintings and sculptures.[86]

The nude almost disappeared from Western art during the Middle Ages, largely due to the attitude of the early Christians,[87] although in Kenneth Clark's famous distinction "naked" figures were still required for some subjects, especially the Last Judgment. This changed with the Renaissance and the rediscovery of classical antiquity, when painters initially used their male apprentices (garzoni) as models, for figures of both genders, as is often clear from their drawings. Leon Battista Alberti recommends drawing from the nude in his De pictura of 1435; as remained usual until the end of the century, he seems only to mean using male models.[88]: 49–50

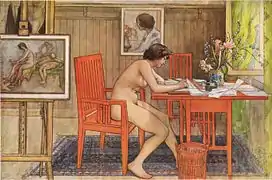

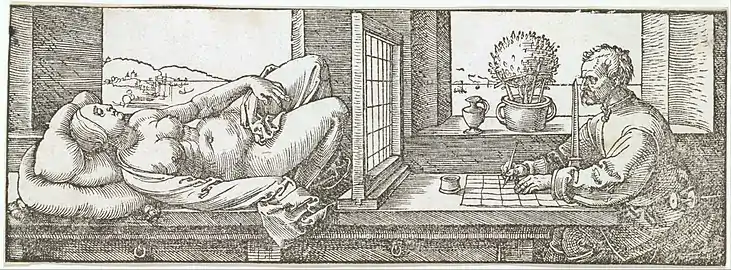

Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman, Albrecht Dürer (c. 1600)

Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman, Albrecht Dürer (c. 1600)

Early modern

Agnès Sorel was a favourite mistress of Charles VII of France. She was the subject of several works of art.

Agnès Sorel was a favourite mistress of Charles VII of France. She was the subject of several works of art. Olympe Pélissier was a French artists' model and the second wife of the Italian composer Gioachino Rossini.

Olympe Pélissier was a French artists' model and the second wife of the Italian composer Gioachino Rossini. Apollonie Sabatier, here shown in Woman Bitten by a Serpent (1847) was a French courtesan, artists' muse and bohémienne in 1850s Paris.

Apollonie Sabatier, here shown in Woman Bitten by a Serpent (1847) was a French courtesan, artists' muse and bohémienne in 1850s Paris. Victorine Meurent (left), known as the favourite model of Édouard Manet, was an artist in her own right. Laure, (right), was a model who regularly worked with Manet.

Victorine Meurent (left), known as the favourite model of Édouard Manet, was an artist in her own right. Laure, (right), was a model who regularly worked with Manet. Fanny Eaton, a Jamaican-born British art model known for her work with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Fanny Eaton, a Jamaican-born British art model known for her work with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Rosina Ferrara, an Italian girl from Capri, became the favorite muse of John Singer Sargent.

Rosina Ferrara, an Italian girl from Capri, became the favorite muse of John Singer Sargent.

Loie Fuller, Modern Dance pioneer, by Toulouse-Lautrec.

Loie Fuller, Modern Dance pioneer, by Toulouse-Lautrec. Misia Sert, a pianist of Polish descent; patron and friend of numerous artists, for whom she regularly posed.

Misia Sert, a pianist of Polish descent; patron and friend of numerous artists, for whom she regularly posed.

Possibly the first images of nude women done from the life are a number of drawings and prints by Albrecht Dürer from the 1490s, which were ahead of Italian practice.[88]: 51–55 The production of female nudes suddenly became important in Venetian painting in the decade after 1500, with works such as Giorgione's Dresden Venus of c. 1510. Venetian painters made relatively little use of drawings, and it has been thought that these works did not involve much use of live models, but this view has recently been challenged.[88]: 55–56 The first Italian artist to regularly use female models for studies is usually thought to have been Raphael, whose drawings of the female nude clearly do not use teenage boys.[88]: 56–60 Michelangelo's earlier Study of a Kneeling Nude Girl for The Entombment (c. 1500) may or may not have used a female model, but if it did this was not his normal practice.[89]

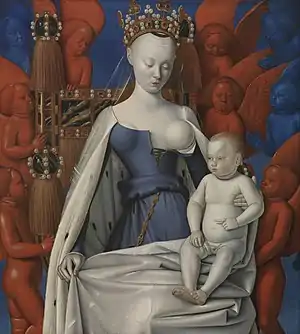

The story of the love between Raphael and his mistress-model Margarita Luti (La Fornarina) is "the archetypal artist-model relationship of Western tradition".[90] There was also a tradition of incorporating donor portraits as minor figures into religious narrative scenes, and several Virgin and Child compositions by court painters are thought to use princesses or other court figures as models for the Virgin Mary; these are sometimes called "disguised portraits".[91]: 3–4, 137 [92] The most notorious of these is the portrayal as the Virgo lactans (or just post-lactans) of Agnès Sorel (died 1450), the mistress of Charles VII of France, in a panel by Jean Fouquet.[91]: 3–4 [93]

Raphael's relationship was probably somewhat untypical, although the Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini records his use, in both Rome and Paris, of servant girls as model, mistress and maid. However, when he broke with one he had difficulty in finding another model, and was forced to rehire her just to pose.[88]: 60–61 Lorenzo Lotto records payments to prostitutes to pose in Venice in 1541, perhaps the earliest record of what long remained an option for artists.[88]: 60

Art modeling as an occupation appeared in the late Renaissance when the establishment of schools for the study of the human figure created a regular demand, and since that time the remuneration offered ensured a continual supply.[85] However, academy models were usually only men until the late 19th century, as were the students.[94] The Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture only allowed female models, clothed, from 1759,[88]: 61 and in London the students at the female branch of the Royal Academy of Art were only allowed to draw suits of armour to practise their figures until the later 19th century.

The status of nude models has fluctuated with the value and acceptance of nudity in art. Maintaining the classical ideals of Greece and Rome into the Christian Era, nudity was prominent in the decoration of Catholic churches in the Renaissance, only to be covered up with draperies or fig leaves by more prudish successors. The Protestant Reformation went even further, destroying many artworks. From being a possibly glamorous occupation celebrating beauty, being a nude model was at other times equivalent to prostitution, practiced by persons without the means to gain more respectable employment. The costumed models used to create historical paintings may not have been a distinct group, since nude studies were done in preparation for any figure painting.

.jpg.webp)

Late modern and contemporary

In 19th-century Paris, a number of models earned a place in art history. Victorine Meurent became a painter herself after posing for several works, including two of the most infamous: Manet's Olympia and Le déjeuner sur l'herbe. Joanna Hiffernan (c. 1843 – after 1903) was an Irish artists' model and muse who was romantically linked with American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler and French painter Gustave Courbet. She is the model for Whistler's painting Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl and is rumored to be the model for Courbet's painting L'Origine du monde. Suzanne Valadon, also a painter, modeled for Pierre-Auguste Renoir (most notably in Dance at Bougival), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and Edgar Degas. She was the mother of the painter Maurice Utrillo.

The second Bal des Quat'z'Arts held in 1893 was a costume ball featuring nude models among the crowd, blurring the distinction between the idealized images in works of art and the real people who posed for them. This was symbolic of other social changes that marked the fin de siècle. Four studio models were convicted of public indecency, which was followed by protests of censorship by students of the École des Beaux-Arts.[95][96]

When Victorian attitudes took hold in England, studies with a live model became more restrictive than they had been in the prior century, limited to advanced classes of students that had already proved their worthiness by copying old master paintings and drawing from plaster casts.[83]: 9 This is in part because many schools were publicly funded, so decisions were under the scrutiny of non-artists.[83]: 12 Modeling was not respectable, and even less so for women. During the same period, the French art atelier system allowed any art student to work from life in a less formal atmosphere, and also admitted women as students. In England, the life class became well established as a central element in art education only with the approach of the 20th century.[83]: 14–16

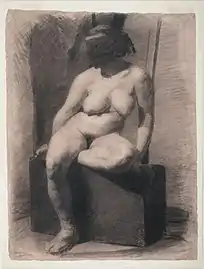

Masked nude, drawing by Thomas Eakins (c. 1863–66)

Masked nude, drawing by Thomas Eakins (c. 1863–66)_-_2_Boys_Boxing_in_atelier-GHP-445992.jpg.webp) Two Boys Boxing at the Art Students League of Philadelphia, by Thomas Eakins

Two Boys Boxing at the Art Students League of Philadelphia, by Thomas Eakins

In the United States, Victorian modesty sometimes required the female model to pose nude with her face draped (Masked Nude by Eakins, for example).[97]: 84 In 1886, Thomas Eakins was famously dismissed from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art for removing the loincloth from a male model in a mixed classroom.[98] European arts academies did not allow women to study the nude at all until the end of the nineteenth century. Even today there remain some schools where the employment of nude models is limited (male models wearing jockstraps) or prohibited, usually for religious reasons.

James Carroll Beckwith's c. 1901 portrait of Evelyn Nesbit, a popular American chorus girl and artists' model.

James Carroll Beckwith's c. 1901 portrait of Evelyn Nesbit, a popular American chorus girl and artists' model. Photograph of Evelyn Nesbit by Gertrude Käsebier, 1903

Photograph of Evelyn Nesbit by Gertrude Käsebier, 1903 Fountain of the Setting Sun (1915) by Adolph Alexander Weinman, modeled by Audrey Munson

Fountain of the Setting Sun (1915) by Adolph Alexander Weinman, modeled by Audrey Munson

In the postmodern era, the nude has returned to gain some acceptance in the art world, but not necessarily the art model. Figure drawing is offered in most art schools, but may not be required for a fine art degree. Peter Steinhart says that in trendy galleries, the nude has become passé,[24]: 21 while according to Wendy Steiner there has been a revival in the importance of the figure as a source of beauty in contemporary art.[99] Some established living artists work from models, but more work from photographs, or their imagination. Yet privately held open drawing sessions with a live model remain as popular as ever.[100]

In popular culture

Films

.jpg.webp)

While there have been a number of films that exploited the artist/model stereotype, a few have more accurately portrayed the working relationship.

- The Artist and the Model (2012) – Set during WWII, an elderly sculptor is prompted to resume working by the arrival of a beautiful Spanish refugee who is willing to pose.[101]

- Camille Claudel (1988) – Depicts Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel working in their studio with models.[102]

- La Belle Noiseuse (1991) — An aging artist is coaxed out of retirement by an aspiring young artist's suggestion that his girlfriend pose nude for a new painting.[103]

- Maze (2000) – The film opens with New York painter and sculptor Lyle Maze (Rob Morrow), who has Tourette syndrome, drawing from a model.[104] Later a friend Callie (Laura Linney), also poses for Maze.

- The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969) - One of Miss Brodie's teenage students, Sandy (Pamela Franklin) poses nude for the art instructor Mr. Lloyd (Robert Stephens).

- Renoir (2012) — Tells the story of Catherine Hessling, the last model of Pierre-Auguste Renoir and the first actress in the films of his son, Jean Renoir.[105]

References

- Bharali, Kannaki (2019). Nude in a Classroom: The Contemporary World of Life Modelling (PhD). City University of New York. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- Mayhew, Margaret (2010). Modelling Subjectivities: Life Drawing, Popular Culture and Contemporary Art Education (PhD). Sydney, Australia: University of Sydney. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- Annette and Luc Vizin (2003). The 20th Century Muse. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-9154-3.

- Phillips, Sarah R. (2006). Modeling Life: Art Models Speak about Nudity, Sexuality and the Creative Process. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6908-8.

- Nicolaides, Kimon (1975). The Natural Way to Draw. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 978-0-395-20548-8.

- Jacobs, Ted Seth (1986). Drawing with an Open Mind. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 978-0-8230-1464-4.

- Berry, William A. (1977). Drawing the Human Form: A Guide to Drawing from Life. New York: Van Nortrand Reinhold Co. ISBN 978-0-442-20717-5.

- Borzello, Frances (2010). The Artist's Model (2nd ed.). Faber & Faber Limited. ISBN 9780571269822.

- Denny, Diana (16 November 2012). "A Day in the Life of Norman Rockwell Model Chuck Marsh". Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- "Register of Artists' Models". Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- "Bay Area Models' Guild". Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- "Life Models Society". Lifemodelssociety.org. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- "KYO – Konstmodellernas yrkesorganisation". Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- "Model's Strike 1941". Trove. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- "Italian Model's Strike 2008". Fox News. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- "Paris Model's Strike 2008". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- Bullock, Linda (2005). Finding Human Form: Artists' Models in Studio and Classroom. Ashville: R.S. Press. ISBN 978-0-9613949-9-8.

- Mann, Sally; Price, Reynolds (1992). Immediate Family. Aperture. ISBN 978-0893815233.

- Gordon, Mary (1996). "Sexualizing Children: Thoughts on Sally Mann". Salmagundi. Skidmore College (111): 144–145. JSTOR 40535995.

- Mann, Sally; Gordon, Mary (1997). "An Exchange on "Sexualizing Children"". Salmagundi (114/115): 228–232. ISSN 0036-3529. JSTOR 40548981. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- Powell, Lynn (2010). Framing Innocence: A Mother's Photographs, a Prosecutor's Zeal, and a Small Town's Response. The New Press. ISBN 978-1595585516.

- "Jock Sturges Biography". Archived from the original on July 17, 2018.

- Harold Maass (July 5, 1990). "Photo Lab Sets Off FBI Probe : Art: Jock Sturges' photographs of nude families are at issue". Los Angeles Times.

- Steinhart, Peter (2004). The Undressed Art: Why We Draw. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4184-8.

- Leber, Holly (2012-02-24). "Art models disrobe to help immortalize the human form". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- Nesich, Hannah (2013-03-21). "Baring It All For Fine Art". The New Paltz Oracle. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

-

- Baker, Laura. "Models 'expose' students to nude art". The Daily Collegian. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- Ben Bourgeois (March 5, 2010). "Yes--They Do Use Nude Models For Art Class". WAFB. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- Rooney, Kathleen (2009). Live Nude Girl: My Life as an Object. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-891-2.

- Rocha, Kimberlina (February 2, 2005). "Art in the Nude". The Collegian. California State University, Fresno. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- Jenkins, Audrey (2014-03-21). "Attention: Will Strip for Art". The Cento. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Artist Model Ad" (PDF). Kansas City Art Institute. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Job Posting". Kishwaukee College. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "CUNY Art Model" (PDF). July 10, 2017. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Careers at UA - Jobs - Job Details - Art Model (Nude)". Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Art Model * | UCnet". Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "University of Utah Jobs - Art Model in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States". Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Make Money". Art & Design. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Students Financial Aid". Western Washington University. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Part-time Position Descriptions: Careers/Opportunities: About: Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design: Indiana University Bloomington". Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Opportunity for Contract Figure Models" (PDF). Art Academy of Cincinnati. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- "Classified Staff, Management and Other Opportunities". Coast Community College. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Amy K. Stewart (March 26, 2008). "UVSC drafts nude-modeling rules". Deseret News.

- "Figure Model Guidelines" (PDF). Ringling College of Art and Design. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Policy for the Study of Nude Models in SIUE Figure Drawing Classes". Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Model Handbook" (PDF). Columbus College of Art and Design. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "RAM Guidelines – Contentious Issues". Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Modeling Q&A" (PDF). St. Olaf College. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Zack Stoycoff (February 20, 2019). "For art's sake". Tulsa World. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Yves Klein, Anthropometries". Tate Modern. January 17, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- Randy Kennedy (March 19, 2010). "Who's Afraid of Marina?". The New York Times.

- Robin Pogrebin (December 20, 2017). "Chuck Close Apologizes After Accusations of Sexual Harassment". THe New York Times. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Johnson, Ken; Pogrebin, Robin (August 19, 2021). "Chuck Close, Artist of Outsized Reality, Dies at 81". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- Christopher Lloyd, Enchanting the Eye, Dutch Paintings of the Golden Age, pp. 49-52, Royal Collection Publications, 2004, ISBN 1-902163-90-7.

- Butler, Ruth (2008). Hidden in the Shadow of the Master: The Model-Wives of Cézanne, Monet, and Rodin. New Haven, United States: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14953-1. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- Geordie Greig (October 17, 2013). "A Daughter's Tale". Vanity Fair.

- Cunningham, Erin (22 October 2013). "New Book Gives A Rare Glimpse Into The Life of Lucian Freud". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Ollman, Arthur (1999). The Model Wife. Little, Brown. ISBN 9780821221709.

- "Life-modelling: the art of poise". Herald Scotland. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Kimono Model". Atelier Kanawa. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- Rachel Kramer Bussel. "Model Behavior". The Village Voice. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- "sitter". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- Pierce, Andrew (2008). "Lucian Freud portrait worth millions destroyed by sitter". Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- "Christie's: Nude (Madonna), 1979". Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "Covid Has Created a Virtual Renaissance for Life Drawing". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- Angelica Frey (May 26, 2020). "The Imperfect but Invaluable Experience of Virtual Figure-Drawing Classes". Artsy.

- "Clothing Not Optional: Fine Art Models Find New Ways To Sketch A Virtual Future". KUNC. NPR. 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- Bishwabijoy, Mitra (2021-03-31). "City artists pitch in to help lockdown-hit nude models". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Body Image and Mental Health: Leading a Life Art Class". Mental Health Foundation. April 26, 2019.

- Manzella, David B. (1973). "Nude in the Classroom". American Journal of Art Therapy. 12 (3).

- "London's Life Models: The Naked Truth". Londonist. 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- Holland, Maggie (2018-01-26). "Baring it all: Student models in nude modeling program at Lamar Dodd discuss art and body positivity". The Red and Black. University of Georgia, Athens. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Home | Figure On Diversity". Figureondiversity. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- Daniel Grant (2011-07-18). "Christian Colleges Struggle with Their Fine Art Programs". Huffington Post. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- Bower, Lorraine (2009-12-29). "Faith–Learning Interaction in Graphic Design Courses in Protestant Evangelical Colleges and Universities". Christian Higher Education. 9 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1080/15363750902973477. ISSN 1536-3759. S2CID 144153863. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- Katelyn Johns (October 19, 2012). "Honor Code and the visual arts". The Daily Universe. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- White, Jenny (March 1, 2012). "Nudity in art is professional, not sexual". Associated Students of Olivet Nazarene University. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- "Art Policy on Nude Models" (PDF). Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- "Policy on the Use of Nude Models in Art". Gordon College. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- Elkins, James (2001). Why Art Cannot Be Taught: A Handbook for Art Students. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-252-06950-5.

- Clark, Kenneth (1956). The Nude – A Study in Ideal Form: Chapter 1. The Naked and the Nude. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01788-4.

- Eaton, E.W. (September 2008). "Feminist philosophy of art". Philosophy Compass. 3 (5): 873–893. doi:10.1111/j.1747-9991.2008.00154.x.

- Postle, M.; Vaughn, W. (1999). The Artist's Model: from Etty to Spencer. London: Merrell Holberton. ISBN 978-1-85894-084-7.

- Rozas, Diana & Gottehrer Bourne, Anita (1999). American Venus: The Extraordinary Life of Audrey Munson, Model and Muse. Los Angeles: Balcony Press.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Models, Artists'". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 640.

- Cooper, Craig (1995). "Hyperides and the trial of Phryne". Phoenix. 49 (4): 303–318. doi:10.2307/1088883. JSTOR 1088883.

- Sorabella, Jean (January 2008). "The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Bernstein, Joanne G. (1992). "The Female Model and the Renaissance Nude: Dürer, Giorgione, and Raphael". Artibus et Historiae. 13 (26): 49–63. doi:10.2307/1483430. ISSN 0391-9064. JSTOR 1483430. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Dunkerton, 186

- Lathers, Marie (2001). Bodies of Art: French Literary Realism and the Artist's Model. University of Nebraska Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8032-2941-9.

- Campbell, Lorne (1990). Renaissance Portraits, European Portrait-Painting in the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04675-8.

- Ainsworth, Maryan W. (January 2008). "Intentional Alterations of Early Netherlandish Painting". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

- Ainsworth, Maryan Wynn et al., From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 192, 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009. ISBN 0-8709-9870-6, google books Archived 2021-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Lathers, Marie (1996). "The Social Construction and Deconstruction of the Female Model in 19th-Century France". Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal. 29 (2): 23–52. ISSN 0027-1276. JSTOR 44029745. Retrieved 2022-10-29.

- Felter-Kerley, Lela (2010). "The Art of Posing Nude: Models, Moralists, and the 1893 Bal Des Quat'z-Arts". French Historical Studies. 33 (1): 69–97. doi:10.1215/00161071-2009-021.

- Kerley, Lela F. (2017-06-07). Uncovering Paris: Scandals and Nude Spectacles in the Belle Époque. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-6634-5.

- Boime, Albert (1974). Strictly Academic: Life Drawing in the Nineteenth Century. Binghamton: State University of New York at Binghamton.OCLC 935594325

- Sewell, Darrel (2001). Thomas Eakins. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-87633-143-6.

- Wendy, Steiner (2001). Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in Twentieth-century Art. The Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-85781-7.

- Gail Gregg (2010-12-01). "Nothing Like the Real Thing". ArtNews.

- "The Artist and the Model (2012)". IMDB. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- "Camille Claudel (1988)". IMDB. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- "Festival de Cannes: La Belle Noiseuse". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Maze (2001)". rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- "A Forger's Impressions of Impressionism". The New York Times. 23 March 2013.

Further reading

- Lipton, Eunice (1992). Alias Olympia: A Woman's Search for Manet's Notorious Model and Her Own Desires. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8609-8.

- Meskimmon, Marsha; Desmarais, Jane; Postle, Martin; Vaughan, William; Vaughan, Martin; West, Shearer; Barringer, Tim (2006). Model and Supermodel: The Artists' Model in British Art and Culture. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6662-7.

- Steiner, Wendy (2010). The Real Thing: the Model in the Mirror of Art. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226772196.

- Waller, Susan (2006). The Invention of the Model: Artists and Models in Paris, 1830–1870. Burlington: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-3484-3.