Assata Shakur

Assata Olugbala Shakur (born JoAnne Deborah Byron; July 16, 1947[lower-alpha 1]) is an American political activist who was a member of the Black Liberation Army (BLA). In 1977, she was convicted in the first-degree murder of State Trooper Werner Foerster during a shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike in 1973. She escaped from prison in 1979 and is currently wanted by the FBI, with a $1 million FBI reward for information leading to her capture, and an additional $1 million reward offered by the Attorney General of New Jersey.[3]

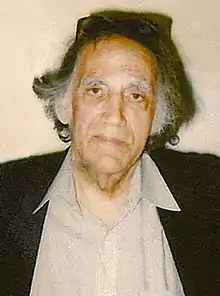

Assata Shakur | |

|---|---|

Photograph taken in 1977 | |

| Born | JoAnne Deborah Byron July 16, 1947[lower-alpha 1] New York City, U.S. |

| Known for | Convicted of murder, one of the FBI's "Most Wanted Terrorists", friend of Afeni Shakur and Mutulu Shakur and often described as their son Tupac Shakur's "godmother" or "step-aunt"[2] |

| Criminal status | Escaped/At large |

| Spouse |

Louis Chesimard

(m. 1967; div. 1970) |

| Children | 1 (Kakuya Shakur) |

| Allegiance | Black Liberation Army (1970/1–1981) Black Panther Party (1970) |

| Conviction(s) | 1977

|

| Criminal penalty | Life sentence |

Reward amount | $1,000,000 |

Capture status | Fugitive |

Wanted by | FBI |

| Escaped | November 2, 1979 |

| This article is part of a series about |

| Black power |

|---|

|

Born in Flushing, Queens, she grew up in New York City and Wilmington, North Carolina. After she ran away from home several times, her aunt, who would later act as one of her lawyers, took her in. She became involved in political activism at Borough of Manhattan Community College and City College of New York. After graduation, she began using the name Assata Shakur, and briefly joined the Black Panther Party. She then joined the BLA, a loosely knit offshoot of the Black Panthers, which engaged in an armed struggle against the US government through tactics including robbing banks and killing police officers and drug dealers.[4]

Between 1971 and 1973, she was charged with several crimes and was the subject of a multi-state manhunt. In May 1973, Shakur was arrested after being wounded in a shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike. Also involved in the shootout were New Jersey State Troopers Werner Foerster and James Harper and BLA members Sundiata Acoli and Zayd Malik Shakur. State Trooper Harper was wounded; Zayd Shakur was killed; State Trooper Foerster was killed. Between 1973 and 1977, Shakur was charged with murder, attempted murder, armed robbery, bank robbery, and kidnapping in relation to the shootout and six other incidents. She was acquitted on three of the charges and three were dismissed. In 1977, she was convicted of the murder of State Trooper Foerster and of seven other felonies related to the 1973 shootout. Her defense had argued medical evidence suggested her innocence since her arm was damaged in the shootout.

While serving a life sentence for murder, Shakur escaped in 1979, with assistance from the BLA and members of the May 19 Communist Organization, from the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women in Union Township, NJ, now the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women. She surfaced in Cuba in 1984, where she was granted political asylum. Shakur has lived in Cuba since, despite US government efforts to have her returned. She has been on the FBI Most Wanted Terrorists list since 2013 as Joanne Deborah Chesimard and was the first woman to be added to this list.[5][6]

Early life and education

Assata Shakur was born Joanne Deborah Byron, in Flushing, Queens, New York City, on July 16, 1947.[7] She lived for three years with her mother, school teacher Doris E. Johnson, and retired grandparents, Lula and Frank Hill.[8]

In 1950, Shakur's parents divorced and she moved with her grandparents to Wilmington, North Carolina. After elementary school, Shakur moved back to Queens to live with her mother and stepfather (her mother had remarried); she attended Parsons Junior High School. Shakur still frequently visited her grandparents in the south. Her family struggled financially and argued frequently; Shakur spent little time at home.[9]

She often ran away, staying with strangers and working for short periods of time, until she was taken in by her mother's sister, Evelyn A. Williams, a civil rights worker who lived in Manhattan.[10] Shakur has said that her aunt was the heroine of her childhood, as she was constantly introducing her to new things. She said that her aunt was "very sophisticated and knew all kinds of things. She was right up my alley because i [sic] was forever asking all kinds of questions. I wanted to know everything." Williams often took the girl to museums, theaters, and art galleries.[11]

Shakur converted to Catholicism as a child and attended the all-girls Cathedral High School, for six months before transferring to public high school.[12] She attended for a while before dropping out. Her aunt helped her to later earn a General Educational Development (GED) degree.[11] Often there were few or no other black students in her Catholic high school class.

Shakur later wrote that teachers seemed surprised when she answered a question in class, as if not expecting black people to be intelligent and engaged. She said she was taught a sugar-coated version of history that ignored the oppression suffered by people of color, especially in the United States. In her autobiography, she wrote: "I didn't know what a fool they had made out of me until I grew up and started to read real history".[13]

Shakur attended Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) and then the City College of New York (CCNY) in the mid-1960s, where she became involved in many political activities, civil rights protests, and sit-ins.[14]

She was arrested for the first time — with 100 other BMCC students — in 1967, on charges of trespassing. The students had chained and locked the entrance to a college building to protest the low numbers of black faculty and the lack of a black studies program.[15] In April 1967, she married Louis Chesimard, a fellow student-activist at CCNY. Their married life ended within a year; they divorced in December 1970. In her 320-page memoir, Shakur gave one paragraph to her marriage, saying that it ended over their differing views of gender roles.[16]

Black Panther Party and Black Liberation Army

After graduation from CCNY, Shakur moved to Oakland, California, where she joined the Black Panther Party (BPP).[17] In Oakland, Shakur worked with the BPP to organize protests and community education programs.[18]

After returning to New York City, Shakur led the BPP chapter in Harlem, coordinating the Free Breakfast Program for children, free clinics, and community outreach.[18] But she soon left the party, disliking the macho behavior of the men and believing that the BPP members and leaders lacked knowledge and understanding of United States black history.[19] Shakur joined the Black Liberation Army (BLA), an offshoot whose members were inspired by the Vietcong and the Algerian independence fighters of the Battle of Algiers. They mounted a campaign of guerilla activities against the U.S. government, using such tactics as planting bombs, holding up banks, and murdering drug dealers and police.[20][21][22]

She began using the name Assata Olugbala Shakur in 1971, rejecting Joanne Chesimard as a "slave name".[11][23] Assata is a West African name, derived from Aisha, said to mean "she who struggles", while Shakur means "thankful one" in Arabic. Olugbala means "savior" in Yoruba.[23] She identified as an African and felt her old name no longer fit: "It sounded so strange when people called me Joanne. It really had nothing to do with me. I didn't feel like no Joanne, or no negro, or no American. I felt like an African woman".[24]

Allegations and manhunt

Beginning in 1971, Shakur was allegedly involved in several incidents of assault and robbery, in which she was charged or identified as wanted for questioning, including attacks on New York City police and bank robberies in the area.

On April 6, 1971, Shakur was shot in the stomach during a struggle with a guest at the Statler Hilton Hotel in Midtown Manhattan. According to police, Shakur knocked on the door of a guest's room, asked "Is there a party going on here?", then displayed a revolver and demanded money.[25] In 1987, Shakur confirmed to a journalist that there was a drug connection in this incident but refused to elaborate.[12]

She was booked on charges of attempted robbery, felonious assault, reckless endangerment, and possession of a deadly weapon, then released on bail.[26] Shakur is alleged to have said that she was glad that she had been shot; afterward, she was no longer afraid to be shot again.[27]

Following an August 23, 1971, bank robbery in Queens, Shakur was sought for questioning. A photograph of a woman (who was later alleged to be Shakur) wearing thick-rimmed black glasses, with a high hairdo pulled tightly over her head, and pointing a gun, was widely displayed in banks. The New York Clearing House Association paid for full-page ads displaying material about Shakur.[28] In 1987, when asked in Cuba about police allegations that the BLA gained funds by conducting bank robberies and theft, Shakur responded, "There were expropriations, there were bank robberies."[12]

On December 21, 1971, Shakur was named by the New York City Police Department as one of four suspects in a hand grenade attack that destroyed a police car and injured two officers in Maspeth, Queens. When a witness identified Shakur and Andrew Jackson from Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) photographs, a 13-state alarm was issued three days after the attack.[29][30][31][32] Law enforcement officials in Atlanta, Georgia, said that Shakur and Jackson had lived together in Atlanta for several months in the summer of 1971.[33][34][35]

Shakur was wanted for questioning for wounding a police officer on January 26, 1972, who was attempting to serve a traffic summons in Brooklyn.[36] After an $89,000 Brooklyn bank robbery on March 1, 1972, a Daily News headline asked: "Was that JoAnne?" Shakur was identified as wanted for questioning after a September 1, 1972, bank robbery in the Bronx.[36] Based on FBI photographs, Monsignor John Powis alleged that Shakur was involved in an armed robbery at Our Lady of the Presentation Church in Brownsville, Brooklyn, on September 14, 1972.[37]

In 1972, Shakur became the subject of a nationwide manhunt after the FBI alleged that she led a Black Liberation Army cell that had conducted a "series of cold-blooded murders of New York City police officers".[38] The FBI said these included the "execution style murders" of New York City Police Officers Joseph Piagentini and Waverly Jones on May 21, 1971, and NYPD officers Gregory Foster and Rocco Laurie on January 28, 1972.[39][40] Shakur was alleged to have been directly involved with the Foster and Laurie murders, and involved tangentially with the Piagentini and Jones murders.[41]

Some sources identify Shakur as the de facto head of the BLA after the arrest of co-founder Dhoruba Moore.[42] Robert Daley, Deputy Commissioner of the New York City Police, for example, described Shakur as "the final wanted fugitive, the soul of the gang, the mother hen who kept them together, kept them moving, kept them shooting".[43] Years later, some police officers argued that her importance in the BLA had been exaggerated by the police. One officer said that they had created a "myth" to "demonize" Shakur because she was "educated", "young and pretty".[44]

As of February 17, 1972, when Shakur was identified as one of four BLA members on a short trip to Chattanooga, Tennessee, she was wanted for questioning (along with Robert Vickers, Twyman Meyers, Samuel Cooper, and Paul Stewart) in relation to police killings, a Queens bank robbery, and the grenade attack on police.[45][46][47] Shakur was reported as one of six suspects in the ambushing of four policemen—two in Jamaica, Queens, and two in Brooklyn—on January 28, 1973.[48]

On April 16, 1981, Shakur was allegedly in the back seat of a van connected with a burglary. After the vehicle was pulled over, two men stepped out of the vehicle and opened fire on NYPD officers John Scarangella and Richard Rainey. The two men were charged with the murder of Officer Scarangella and attempted murder of Officer Rainey.[49]

By June 1973, an apparatus that would become the FBI's Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF)[50] was issuing nearly daily briefings on Shakur's status and the allegations against her.[51][52]

According to Cleaver and Katsiaficas, the FBI and local police "initiated a national search-and-destroy mission for suspected BLA members, collaborating in stakeouts that were the products of intensive political repression and counterintelligence campaigns like NEWKILL". They "attempted to tie Assata to every suspected action of the BLA involving a woman".[53] The JTTF would later serve as the "coordinating body in the search for Assata and the renewed campaign to smash the BLA", after her escape from prison.[52] After her capture, however, Shakur was not charged with any of the crimes for which she was purportedly the subject of the manhunt.[38][54]

Shakur and others[38][54][55] claim that she was targeted by the FBI's COINTELPRO as a result of her involvement with the black liberation organizations.[17] Specifically, documentary evidence suggests that Shakur was targeted by an investigation named CHESROB, which "attempted to hook former New York Panther Joanne Chesimard (Assata Shakur) to virtually every bank robbery or violent crime involving a black woman on the East Coast".[56] Although named after Shakur, CHESROB (like its predecessor, NEWKILL) was not limited to Shakur.[57]

Years later when she was living in Cuba, Shakur was asked about the BLA's alleged involvement in the killings of police officers. She said, "In reality, armed struggle historically has been used by people to liberate themselves... But the question lies in when do people use armed struggle... There were people [in the BLA] who absolutely took the position that it was just time to resist, and if black people didn't start to fight back against police brutality and didn't start to wage armed resistance, we would be annihilated."[12]

New Jersey Turnpike shootout

On May 2, 1973, at about 12:45 a.m.,[58] Assata Shakur, along with Zayd Malik Shakur (born James F. Costan) and Sundiata Acoli (born Clark Squire), were stopped on the New Jersey Turnpike in East Brunswick for driving with a broken tail light by State Trooper James Harper, backed up by Trooper Werner Foerster in a second patrol vehicle.[59] The vehicle was "slightly" exceeding the speed limit.[58][60] Recordings of Trooper Harper calling the dispatcher were played at the trials of both Acoli and Assata Shakur.[59][61]

The stop occurred 200 yards (183 m) south of what was then the Turnpike Authority administration building.[58][61][62] Acoli was driving the two-door vehicle, Assata Shakur was seated in the right front seat, and Zayd Shakur was in the right rear seat.[63][lower-alpha 2] Trooper Harper asked the driver for identification, noticed a discrepancy, asked him to get out of the car, and questioned him at the rear of the vehicle.[58]

With the questioning of Acoli, accounts by participants of the confrontation begin to differ (see the witnesses section below).[64] A shootout ensued in which Trooper Foerster was shot twice in the head with his own gun and killed,[59][64] Zayd Shakur was killed, and Assata Shakur and Trooper Harper were wounded.

According to initial police statements, at this point one or more of the suspects had begun firing with semiautomatic handguns, and Trooper Foerster fired four times before falling mortally wounded.[58] At Acoli's trial, Harper testified that the gunfight started "seconds" after Foerster arrived at the scene.[63] At this trial, Harper said that Foerster reached into the vehicle, pulled out and held up a semi-automatic pistol and ammunition magazine, and said "Jim, look what I found",[63] while facing Harper at the rear of the vehicle.[65] The police ordered Assata Shakur and Zayd Shakur to put their hands on their laps and not to move; Harper said that Assata Shakur reached down to the right of her right leg, pulled out a pistol, and shot him in the shoulder, after which he retreated to behind his vehicle. Questioned by prosecutor C. Judson Hamlin, Harper said he saw Foerster shot just as Assata Shakur was hit by bullets from Harper's gun.[63] In his opening statement to a jury, Hamlin said that Acoli shot Foerster with a .38 caliber semiautomatic pistol and used Foerster's own gun to "execute him".[66] According to the testimony of State Police investigators, two jammed semi-automatic pistols were discovered near Foerster's body.[67]

Acoli drove the car (a white Pontiac LeMans with Vermont license plates)[62]—which contained Assata Shakur, who was wounded, and Zayd Shakur, who was dead or dying—5 miles (8 km) down the road.[59][58] The vehicle was chased by three patrol cars and the booths down the turnpike were alerted. Acoli stopped and exited the car and, after being ordered to halt by a trooper, fled into the woods as the trooper emptied his gun.[58] Assata Shakur walked toward the trooper with her bloodied arms raised in surrender.[58] Acoli was captured after a 36-hour manhunt—involving 400 people, state police helicopters, and bloodhounds.[58][68][69] Zayd Shakur's body was found in a nearby gully along the road.[58]

According to a New Jersey Police spokesperson, Assata Shakur was on her way to a "new hideout in Philadelphia" and "heading ultimately for Washington". A book in the vehicle was said to contain a list of potential BLA targets.[58] Assata Shakur testified she was on her way to Baltimore for a job as a bar waitress.[70]

With gunshot wounds in both arms and a shoulder, Assata Shakur was moved to Middlesex General Hospital under "heavy guard" and was reported to be in "serious condition". Trooper Harper was wounded in the left shoulder, reported in "good" condition, and given a protective guard at the hospital.[58][68] Assata Shakur was interrogated and arraigned from her hospital bed.[71]

Her defense team alleged that her medical care during this period was "substandard".[11][72][73][74]

She was transferred from Middlesex General Hospital in New Brunswick to Roosevelt Hospital in Edison after her lawyers obtained a court order from Judge John Bachman,[75] and then transferred to Middlesex County Workhouse a few weeks later.[76]

During an interview, Assata Shakur discussed her treatment by the police and medical staff at Middlesex General Hospital. She said that the police beat and choked her and were "doing everything that they could possibly do as soon as the doctors or nurses would go outside".[77]

Criminal charges and dispositions

Between 1973 and 1977, in New York and New Jersey, Shakur was indicted ten times, resulting in seven different criminal trials. Shakur was charged with two bank robberies, the kidnapping of a Brooklyn heroin dealer, the attempted murder of two Queens police officers stemming from a January 23, 1973, failed ambush, and eight other felonies related to the Turnpike shootout.[38][78] Of these trials, three resulted in acquittals, one in a hung jury, one in a change of venue, one in a mistrial due to pregnancy, and one in a conviction. Three indictments were dismissed without trial.[78]

| Criminal charge | Court | Arraignment | Proceedings | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attempted armed robbery at Statler Hilton Hotel April 5, 1971 |

New York Supreme Court, New York County | November 22, 1977 | None | Dismissed |

| Bank robbery in Queens August 23, 1971 |

United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York | July 20, 1973 | January 5–16, 1976 | Acquitted |

| Bank robbery in Bronx: Conspiracy, robbery, and assault with a deadly weapon September 1, 1972 |

United States District Court for the Southern District of New York | August 1, 1973 | December 3–14, 1973 | Hung jury |

| December 19–28, 1973 | Acquitted | |||

| Kidnapping of James E. Freeman December 28, 1972 |

N.Y. Supreme Court, Kings County | May 30, 1974 | September 6 – December 19, 1975 | Acquitted |

| Murder of Richard Nelson January 2, 1973 |

N.Y. Supreme Court, New York County | May 29, 1974 | None | Dismissed |

| Attempted murder of policemen Michael O'Reilly and Roy Polliana January 23, 1973 |

N.Y. Supreme Court, Queens County | May 11, 1974 | None | Dismissed |

| Turnpike shootout: First-degree murder, second-degree murder, atrocious assault and battery, assault and battery against a police officer, assault with a dangerous weapon, assault with intent to kill, illegal possession of a weapon, and armed robbery May 2, 1973 |

N.J. Superior Court, Middlesex County | May 3, 1973 | October 9–23, 1973 | Change of venue |

| January 1 – February 1, 1974 | Mistrial due to pregnancy | |||

| February 15 – March 25, 1977 | Convicted | |||

| Source: Shakur, 1987, p. xiv. | ||||

Turnpike shootout change of venue

On the charges related to the New Jersey Turnpike shootout, New Jersey Superior Court Judge Leon Gerofsky ordered a change of venue in 1973 from Middlesex to Morris County, New Jersey, saying "it was almost impossible to obtain a jury here comprising people willing to accept the responsibility of impartiality so that defendants will be protected from transitory passion and prejudice."[79] Polls of residents in Middlesex County, where Acoli had been convicted less than three years earlier,[80] showed that 83% knew Shakur's identity and 70% believed that she was guilty.[62]

Bronx bank robbery mistrial

In December 1973, Shakur was tried for a September 29, 1972, $3,700 robbery of the Manufacturer's Hanover Trust Company in the Bronx, along with co-defendant Kamau Sadiki (born Fred Hilton).[81][82] In light of the pending murder prosecution against Shakur in New Jersey state court, her lawyers requested that the trial be postponed for six months to permit further preparation. Judge Lee P. Gagliardi denied a postponement, and the Second Circuit denied Shakur's petition for mandamus.[83] In protest, the lawyers stayed mute, and Shakur and Sadiki conducted their own defense.[81][82] Seven other BLA members were indicted by District Attorney Eugene Gold in connection with the series of holdups and shootings on the same day,[84] who—according to Gold—represented the "top echelon" of the BLA as determined by a year-long investigation.[85]

The prosecution's case rested largely on the testimony of two men who had pleaded guilty to participating in the holdup.[86] The prosecution called four witnesses: Avon White and John Rivers (both of whom had already pled guilty to the robbery) and the manager and teller of the bank.[87] White and Rivers, although having pled guilty, had not yet been sentenced for the robbery and were promised that the charges would be dropped in exchange for their testimony.[87] White and Rivers testified that Shakur had guarded one of the doors with a .357 magnum pistol and that Sadiki had served as a lookout and drove the getaway truck during the robbery; neither White nor Rivers was cross-examined due to the defense attorney's refusal to participate in the trial.[87] Shakur's aunt and lawyer, Evelyn Williams, was cited for contempt after walking out of the courtroom after many of her attempted motions were denied.[81] The trial was delayed for a few days after Shakur was diagnosed with pleurisy.[88]

During the trial, the defendants were escorted to a "holding pen" outside the courtroom several times after shouting complaints and epithets at Judge Gagliardi.[89] While in the holding pen, they listened to the proceedings over loudspeakers.[90] Both defendants were repeatedly cited for contempt of court and eventually barred from the courtroom, where the trial continued in their absence.[81] A contemporary New York Times editorial criticized Williams for failing to maintain courtroom "decorum," comparing her actions to William Kunstler's recent contempt conviction for his actions during the "Chicago Seven" trial.[91]

Sadiki's lawyer, Robert Bloom, attempted to have the trial dismissed and then postponed due to new "revelations" regarding the credibility of White, a former co-defendant by then working for the prosecution.[92] Bloom had been assigned to defend Sadiki/Hilton over the summer, but White was not disclosed as a government witness until right before the trial.[93] Judge Gagliardi instructed both the prosecution and the defense not to bring up Shakur or Sadiki's connections to the BLA, saying they were "not relevant".[92] Gagliardi denied requests by the jurors to pose questions to the witnesses—either directly or through him—and declined to provide the jury with information they requested about how long the defense had been given to prepare, saying it was "none of their concern".[94] This trial resulted in a hung jury and then a mistrial, when the jury reported to Gagliardi that they were hopelessly deadlocked for the fourth time.[93]

Bronx bank robbery retrial

The retrial was delayed for one day to give the defendants more time to prepare.[95] The new jury selection was marked by attempts by Williams to be relieved of her duties, owing to disagreements with Shakur as well as with Hilton's attorney.[96] Judge Arnold Bauman denied the application, but directed another lawyer, Howard Jacobs, to defend Shakur while Williams remained the attorney of record.[96] Shakur was ejected following an argument with Williams, and Hilton left with her as jury selection continued.[97] After the selection of twelve jurors (60 were excused), Williams was allowed to retire from the case, with Shakur officially representing herself, assisted by lawyer Florynce Kennedy.[98] In the retrial, White testified that the six alleged robbers had saved their hair clippings to create disguises, and identified a partially obscured head and shoulder in a photo taken from a surveillance camera as Shakur's.[99] Kennedy objected to this identification on the grounds that the prosecutor, assistant United States attorney Peter Truebner, had offered to stipulate that Shakur was not depicted in any of the photographs.[99] Although both White and Rivers testified that Shakur was wearing overalls during the robbery, the person identified as Shakur in the photograph was wearing a jacket.[100] The defense attempted to discredit White on the grounds that he had spent eight months in Matteawan Hospital for the Criminally Insane in 1968, and White countered that he had faked insanity (by claiming to be Allah in front of three psychiatrists) to get transferred out of prison.[101]

Shakur personally cross-examined the witnesses, getting White to admit that he had once been in love with her; the same day, one juror (who had been frequently napping during the trial) was replaced with an alternate.[102] During the retrial, the defendants repeatedly left or were thrown out of the courtroom.[103] Both defendants were acquitted in the retrial; six jurors interviewed after the trial stated that they did not believe the two key prosecution witnesses.[100] Shakur was immediately returned to Morristown, New Jersey, under a heavy guard following the trial.[100] Louis Chesimard (Shakur's ex-husband) and Paul Stewart, the other two alleged robbers, had been acquitted in June.[104]

Turnpike shootout mistrial

The Turnpike shootout proceedings continued with Judge John E. Bachman in Middlesex County.[105] New Jersey Superior Court Judge Leon Gerofsky ordered a change of venue in 1973 from Middlesex to Morris County, New Jersey, saying "it was almost impossible to obtain a jury here comprising people willing to accept the responsibility of impartiality so that defendants will be protected from transitory passion and prejudice."[79] Morris County, had a far smaller black population than Middlesex County.[106] On this basis, Shakur unsuccessfully attempted to remove the trial to federal court.[107]

Before jury selection was complete, it was discovered that Shakur was pregnant. Due to the possibility of miscarriage, the prosecution successfully requested a mistrial for Shakur; Acoli's trial continued.[108][109][110]

Attempted murder dismissal

Shakur and four others (including Fred Hilton, Avon White, and Andrew Jackson) were indicted in the State Supreme Court in the Bronx on December 31, 1973, on charges of attempting to shoot and kill two policemen—Michael O'Reilly and Roy Polliana, who were wounded but had since returned to duty—in an ambush in St. Albans, Queens on January 28, 1973.[111] On March 5, 1974, two new defendants (Jeannette Jefferson and Robert Hayes) were named in an indictment involving the same charges.[112] On April 26, while Shakur was pregnant,[108] New Jersey Governor Brendan Byrne signed an extradition order to move Shakur to New Jersey to face two counts of attempted murder, attempted assault, and possession of dangerous weapons related to the alleged ambush; however, Shakur declined to waive her right to an extradition hearing, and asked for a full hearing before Middlesex County Court Judge John E. Bachman.[113]

Shakur was extradited to New York City on May 6,[114] arraigned on May 11 (pleading not guilty), and remanded to jail by Justice Albert S. McGrover of the State Supreme Court, pending a pretrial hearing on July 2.[115] In November 1974, New York State Supreme Court Justice Peter Farrell dismissed the attempted murder indictment because of insufficient evidence, declaring "The court can only note with disapproval that virtually a year has passed before counsel made an application for the most basic relief permitted by law, namely an attack on the sufficiency of the evidence submitted by the grand jury."[116]

Kidnapping trial

Shakur was indicted on May 30, 1974, on the charge of having robbed a Brooklyn bar and kidnapping bartender James E. Freeman for ransom.[115] Shakur and co-defendant Ronald Myers were accused of entering the bar with pistols and shotguns, taking $50 from the register, kidnapping the bartender, leaving a note demanding a $20,000 ransom from the bar owner, and fleeing in a rented truck.[117] Freeman was said to have later escaped unhurt.[117] The text of Shakur's opening statement in the trial is reproduced in her autobiography.[118] Shakur and co-defendant Ronald Myers were acquitted on December 19, 1975, after seven hours of jury deliberation, ending a three-month trial in front of Judge William Thompson.[117]

Queens bank robbery trial

In July 1973, after being indicted by a grand jury, Shakur pleaded not guilty in Federal Court in Brooklyn to an indictment related to a $7,700 robbery of the Bankers Trust Company bank in Queens on August 31, 1971.[119] Judge Jacob Mishlerset set a tentative trial date of November 5 that year.[120][121] The trial was delayed until 1976,[119] when Shakur was represented by Stanley Cohen and Evelyn Williams.[122] In this trial, Shakur acted as her own co-counsel and told the jury in her opening testimony:

I have decided to act as co-counsel, and to make this opening statement, not because I have any illusions about my legal abilities, but, rather, because there are things that I must say to you. I have spent many days and nights behind bars thinking about this trial, this outrage. And in my own mind, only someone who has been so intimately a victim of this madness as I have can do justice to what I have to say.[123]

One bank employee testified that Shakur was one of the bank robbers, but three other bank employees (including two tellers) testified that they were uncertain.[122] The prosecution showed surveillance photos of four of the six alleged robbers, contending that one of them was Shakur wearing a wig. Shakur was forcibly subdued and photographed by the FBI on the judge's order, after having refused to cooperate, believing that the FBI would use photo manipulation; a subsequent judge determined that the manners in which the photos were obtained violated Shakur's rights and ruled the new photos inadmissible.[81] In her autobiography, Shakur recounts being beaten, choked, and kicked on the courtroom floor by five marshals, as Williams narrated the events to ensure they would appear on the court record.[124] Shortly after deliberation began, the jury asked to see all the photographic exhibits taken from the surveillance footage.[122] The jury determined that a widely circulated FBI photo allegedly showing Shakur participating in the robbery was not her.[125]

Shakur was acquitted after seven hours of jury deliberation on January 16, 1976,[122] and was immediately remanded back to New Jersey for the Turnpike trial.[126] The actual transfer took place on January 29.[127] She was the only one of the six suspects in the robbery to be brought to trial.[122] Andrew Jackson and two others indicted for the same robbery pleaded guilty; Jackson was sentenced to five years in prison and five years' probation; another was shot and killed in a gunfight in Florida on December 31, 1971, and the last remained at large at the time of Shakur's acquittal.[119][122]

Turnpike shootout retrial

By the time she was retried in 1977, Acoli had already been convicted of shooting and murdering Foerster.[63] The prosecution argued that Assata had fired the bullets that had wounded Harper, while the defense argued that the now deceased Zayd had fired them.[128] Based on New Jersey law, if Shakur's presence at the scene could be considered as "aiding and abetting" the murder of Foerster, she could be convicted even if she had not fired the bullets which had killed him.[129]

A total of 289 articles had been published in the local press relating to the various crimes with which Shakur had been accused.[62] Shakur again attempted to remove the trial to federal court. The United States District Court for the District of New Jersey denied the petition and also denied Shakur an injunction against the holding of trial proceedings on Fridays.[59][130][131] An en banc panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit affirmed.[132]

The nine-week trial was widely publicized, and was even reported on by the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS).[62][133] During the trial, hundreds of civil rights campaigners demonstrated outside of the Middlesex County courthouse each day.[62]

Following the 13-minute opening statement by Edward J. Barone, the first assistant Middlesex County prosecutor (directing the case for the state), William Kunstler (the chief of Shakur's defense staff) moved immediately for a mistrial, calling the eight-count grand jury indictment "adversary proceeding solely and exclusively under the control of the prosecutor", whom Kunstler accused of "improper prejudicial remarks"; Judge Theodore Appleby, noting the frequent defense interruptions that had characterized the previous days' jury selection, denied the motion.[134]

On February 23, Shakur's attorneys filed papers asking Judge Appleby to subpoena FBI Director Clarence Kelley, Senator Frank Church and other federal and New York City law enforcement officials to testify about the Counter Intelligence Program, which they alleged was designed to harass and disrupt black activist organizations.[67] Kunstler had previously been successful in subpoenaing Kelley and Church for the trials of American Indian Movement (AIM) members charged with murdering FBI agents.[67] The motion (argued March 2)—which also asked the court to require the production of memos, tapes, documents, and photographs of alleged COINTELPRO involvement from 1970 to 1973—was denied.[67][135]

Shakur herself was called as a witness on March 15, the first witness called by the defense; she denied shooting either Harper or Foerster, and also denied handling a weapon during the incident. She was questioned by her own attorney, Stuart Ball, for under 40 minutes, and then cross-examined by Barone for less than two hours (see the Witnesses section below).[70] Ball's questioning ended with the following exchange:

On that night of May 2[n]d, did you shoot, kill, execute or have anything to do with the death of Trooper Werner Foerster?

No.

Did you shoot or assault Trooper James Harper?

No.[70]

Under cross-examination, Shakur was unable to explain how three magazines of ammunition and 16 live shells had gotten into her shoulder bag; she also admitted to knowing that Zayd Shakur carried a gun at times, and specifically to seeing a gun sticking out of Acoli's pocket while stopping for supper at a Howard Johnson's restaurant shortly before the shooting.[70] Shakur admitted to carrying an identification card with the name "Justine Henderson" in her billfold the night of the shootout, but denied using any of the aliases on the long list that Barone proceeded to read.[70]

Defense attorneys

Shakur's defense attorneys were William Kunstler (the chief of Shakur's defense staff),[134] Stuart Ball, Robert Bloom, Raymond A. Brown,[136] Stanley Cohen (who died of unknown causes early on in the Turnpike trial), Lennox Hinds, Florynce Kennedy, Louis Myers, Laurence Stern, and Evelyn Williams, Shakur's aunt.[78][134][137] Of these attorneys, Kunstler, Ball, Cohen, Myers, Stern and Williams appeared in court for the turnpike trial.[138][139] Kunstler became involved in Shakur's trials in 1975, when contacted by Williams, and commuted from New York City to New Brunswick every day with Stern.[140]

Her attorneys, in particular Lennox Hinds, were often held in contempt of court, which the National Conference of Black Lawyers cited as an example of systemic bias in the judicial system.[141] The New Jersey Legal Ethics Committee also investigated complaints against Hinds for comparing Shakur's murder trial to "legalized lynching"[142] undertaken by a "kangaroo court".[62][143] Hinds' disciplinary proceeding reached the U.S. Supreme Court in Middlesex County Ethics Committee v. Garden State Bar Ass'n (1982).[144] According to Kunstler's autobiography, the sizable contingent of New Jersey State Troopers guarding the courthouse were under strict orders from their commander, Col. Clinton Pagano, to completely shun Shakur's defense attorneys.[145]

Judge Appleby also threatened Kunstler with dismissal and contempt of court after he delivered an October 21, 1976, speech at nearby Rutgers University that in part discussed the upcoming trial,[146] but later ruled that Kunstler could represent Shakur.[147] Until obtaining a court order, Kunstler was forced to strip naked and undergo a body search before each visit with Shakur—during which Shakur was shackled to a bed by both ankles.[62] Judge Appleby also refused to investigate a burglary of her defense counsel's office that resulted in the disappearance of trial documents,[135] amounting to half of the legal papers related to her case.[148] Her lawyers also claimed that their offices were bugged.[81]

Witnesses

Sundiata Acoli, Assata Shakur, Trooper Harper, and a New Jersey Turnpike driver who saw part of the incident were the only surviving witnesses.[149] Acoli did not testify or make any pre-trial statements, nor did he testify in his own trial or give a statement to the police.[150] The driver traveling north on the turnpike testified that he had seen a State Trooper struggling with a Black man between a white vehicle and a State Trooper car, whose revolving lights illuminated the area.[149]

Shakur testified that Trooper Harper shot her after she raised her arms to comply with his demand. She said that the second shot hit her in the back as she turned to avoid it, and that she fell onto the road for the duration of the gunfight before crawling back into the backseat of the Pontiac—which Acoli drove 5 miles (8 km) down the road and parked. She testified that she remained there until State Troopers dragged her onto the road.[64][149]

Trooper Harper's official reports state that after he stopped the Pontiac, he ordered Acoli to the back of the vehicle for Trooper Foerster—who had arrived on the scene—to examine his driver's license.[149] The reports then state that after Acoli complied, and as Harper was looking inside the vehicle to examine the registration, Trooper Foerster yelled and held up an ammunition magazine as Shakur simultaneously reached into her red pocketbook, pulled out a 9mm handgun and fired at him.[149] Trooper Harper's reports then state that he ran to the rear of his car and shot at Shakur who had exited the vehicle and was firing from a crouched position next to the vehicle.[149]

Jury

A total of 408 potential jurors were questioned during the voir dire, which concluded on February 14.[134] All of the 15 jurors—ten women and five men—were white, and most were under thirty years old.[134][151] Five jurors had personal ties to State Troopers (one girlfriend, two nephews, and two friends).[135][152] A sixteenth female juror was removed before the trial formally opened, when it was determined that Sheriff Joseph DeMarino of Middlesex County, while a private detective several years earlier, had worked for a lawyer who represented the juror's husband.[134] Judge Appleby repeatedly denied Kunstler's requests for DeMarino to be removed from his responsibilities for the duration of the trial "because he did not divulge his association with the juror".[134]

One prospective juror was dismissed for reading Target Blue,[153] a book by Robert Daley, a former New York City Deputy Police Commander, which dealt in part with Shakur and had been left in the jury assembly room.[154] Before the jury entered the courtroom, Judge Appleby ordered Shakur's lawyers to remove a copy of Roots: The Saga of an American Family by Alex Haley from a position on the defense counsel table easily visible to jurors.[134] The Roots TV miniseries adapted from the book and shown shortly before the trial was believed to have evoked feelings of "guilt and sympathy" with many white viewers.[134]

Shakur's attorneys sought a new trial on the grounds that one jury member, John McGovern, had violated the jury's sequestration order.[155] Judge Appleby rejected Kunstler's claim that the juror had violated the order.[156] McGovern later sued Kunstler for defamation;[157] Kunstler eventually publicly apologized to McGovern and paid him a small settlement.[158] Additionally, in his autobiography, Kunstler alleged that he later learned from a law enforcement agent that a New Jersey State Assembly member had addressed the jury at the hotel where they were sequestered, urging them to convict Shakur.[158]

Medical evidence

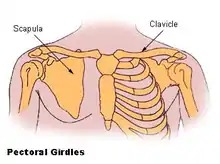

A key element of Shakur's defense was medical testimony meant to demonstrate that she was shot with her hands up and that she would have been subsequently unable to fire a weapon. A neurologist testified that the median nerve in Shakur's right arm was severed by the second bullet, making her unable to pull a trigger.[110] Neurosurgeon Dr. Arthur Turner Davidson, Associate Professor of Surgery at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, testified that the wounds in her upper arms, armpit and chest, and severed median nerve that instantly paralyzed her right arm, would only have been caused if both arms were raised, and that to sustain such injuries while crouching and firing a weapon (as described in Trooper Harper's testimony) "would be anatomically impossible".[62][159]

Davidson based his testimony on an August 4, 1976, examination of Shakur and on X-rays taken immediately after the shootout at Middlesex General Hospital.[159] Prosecutor Barone questioned whether Davidson was qualified to make such a judgment 39 months after the injury; Barone proceeded to suggest (while a female Sheriff's attendant acted out his suggestion) that Shakur was struck in the right arm and collar bone and "then spun around by the impact of the bullet so an immediate second shot entered the fleshy part of her upper left arm" to which Davidson replied "Impossible."[159]

Dr. David Spain, a pathologist from Brookdale Community College, testified that her bullet scars as well as X-rays supported her claim that her arms were raised, and that there was "no conceivable way" the first bullet could have hit Shakur's clavicle if her arm was down.[128][160]

Judge Appleby eventually cut off funds for any further expert defense testimony.[62] Shakur, in her autobiography, and Williams, in Inadmissible Evidence, both claim that it was difficult to find expert witnesses for the trial, because of the expense and because most forensic and ballistic specialists declined on the grounds of a conflict of interest when approached because they routinely performed such work for law enforcement officials.[161]

Other evidence

According to Angela Davis, neutron activation analysis that was administered after the shootout showed no gunpowder residue on Shakur's fingers and forensic analysis performed at the Trenton, New Jersey, crime lab and the FBI crime labs in Washington, D.C., did not find her fingerprints on any weapon at the scene.[162] According to tape recordings and police reports made several hours after the shoot-out, when Harper returned on foot to the administration building 200 yards (183 m) away, he did not report Foerster's presence at the scene; no one at headquarters knew of Foerster's involvement in the shoot-out until his body was discovered beside his patrol car, more than an hour later.[62][12]

Conviction and sentencing

On March 24, the jurors listened for 45 minutes to a rereading of testimony of the State Police chemist regarding the blood found at the scene, on the LeMans, and Shakur's clothing.[64] That night, the second night of jury deliberation, the jury asked Judge Appleby to repeat his instructions regarding the four assault charges 30 minutes before retiring for the night, which led to speculation that the jury had decided in Shakur's favor on the remaining charges, especially the two counts of murder.[64] Appleby reiterated that the jury must consider separately the four assault charges (atrocious assault and battery, assault on a police officer acting in the line of duty, assault with a deadly weapon, and assault with intent to kill), each of which carried a total maximum penalty of 33 years in prison.[64] The other charges were: first-degree murder (of Foerster), second-degree murder (of Zayd Shakur), illegal possession of a weapon, and armed robbery (related to Foerster's service revolver).[138] The jury also asked Appleby to repeat the definitions of "intent" and "reasonable doubt".[64]

Shakur was convicted on all eight counts: two murder charges, and six assault charges.[138] Upon hearing the verdict, Shakur said—in a barely audible voice— "I am ashamed that I have even taken part in this trial", and that the jury was racist and had "convicted a woman with her hands up".[138] When Judge Appleby told the court attendants to "remove the prisoner", Shakur herself replied: "the prisoner will walk away on her own feet".[138] After Joseph W. Lewis, the jury foreman, read the verdict, Kunstler asked that the jury be removed before alleging that one juror had violated the sequestration order (see above).[138]

At the post-trial press conference, Kunstler blamed the verdict on racism, stating that "the white element was there to destroy her". When asked by a reporter why, if that were the case, it took the jury 24 hours to reach a verdict, Kunstler replied, "That was just a pretense." A few minutes later the prosecutor Barone disagreed with Kunstler's assessment saying the trial's outcome was decided "completely on the facts".[138]

At Shakur's sentencing hearing on April 25, Appleby sentenced her to 26 to 33 years in state prison (10 to 12 for the four counts of assault, 12 to 15 for robbery, 2 to 3 for armed robbery, plus 2 to 3 for aiding and abetting the murder of Foerster), to be served consecutively with her mandatory life sentence. However, Appleby dismissed the second-degree murder of Zayd Shakur, as the New Jersey Supreme Court had recently narrowed the application of the law.[163] Appleby finally sentenced Shakur to 30 days in the Middlesex County Workhouse for contempt of court, concurrent with the other sentences, for refusing to rise when he entered the courtroom.[163] To become eligible for parole, Shakur would have had to serve a minimum of 25 years, which would have included her four years in custody during the trials.[163]

Nelson murder dismissal

In October 1977, New York State Superior Court Justice John Starkey dismissed murder and robbery charges against Shakur related to the death of Richard Nelson during a hold-up of a Brooklyn social club on December 28, 1972, ruling that the state had delayed too long in bringing her to trial. Judge Starkey said, "People have constitutional rights, and you can't shuffle them around."[164] The case was delayed in being brought to trial as a result of an agreement between the governors of New York and New Jersey as to the priority of the various charges against Shakur.[164] Three other defendants were indicted in relation to the same holdup: Melvin Kearney, who died in 1976 from an eight-floor fall while trying to escape from the Brooklyn House of Detention, Twymon Myers, who was killed by police while a fugitive, and Andrew Jackson, the charges against whom were dismissed when two prosecution witnesses could not identify him in a lineup.[164]

Attempted robbery dismissal

On November 22, 1977, Shakur pleaded not guilty to an attempted armed robbery indictment stemming from the 1971 incident at the Statler Hilton Hotel.[165] Shakur was accused of attempting to rob a Michigan man staying at the hotel of $250 of cash and personal property.[165] The prosecutor was C. Richard Gibbons.[165] The charges were dismissed without trial.[166]

Imprisonment

After the Turnpike shootings, Shakur was briefly held at the Garden State Youth Correctional Facility[167] in Yardville, Burlington County, New Jersey, and later moved to Rikers Island Correctional Institution for Women in New York City[10] where she was kept in solitary confinement[168][169] for 21 months. Shakur's only daughter, Kakuya Shakur, was conceived during her trial[108] and born on September 11, 1974, in the "fortified psychiatric ward" at Elmhurst General Hospital in Queens,[122][170] where Shakur stayed for a few days before being returned to Rikers Island. In her autobiography, Shakur claims that she was beaten and restrained by several large female officers after refusing a medical exam from a prison doctor shortly after giving birth.[124] After a bomb threat was made against Judge Appleby, Sheriff Joseph DeMarino lied to the press about the exact date of her transfer to Clinton Correctional Facility for Women; He later claimed the threat to be the cause of his falsification.[171] She was also transferred from the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women to a special area staffed by women guards at the Garden State Youth Correctional Facility, where she was the only female inmate,[172] for "security reasons".[173] When Kunstler first took on Shakur's case (before meeting her), he described her basement cell as "adequate", which nearly resulted in his dismissal as her attorney.[145] On May 6, 1977, Judge Clarkson Fisher, of the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey, denied Shakur's request for an injunction requiring her transfer from the all-male facility to Clinton Correctional Facility for Women; the Third Circuit affirmed.[169][174][175]

On April 8, 1978, Shakur was transferred to Alderson Federal Prison Camp in Alderson, West Virginia, where she met Puerto Rican nationalist Lolita Lebrón[10] and Mary Alice, a Catholic nun, who introduced Shakur to the concept of liberation theology.[176] At Alderson, Shakur was housed in the Maximum Security Unit, which also contained several members of the Aryan Sisterhood as well as Sandra Good and Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, followers of Charles Manson.[177]

On February 20, 1979,[178] after the Maximum Security Unit at Alderson was closed,[176] Shakur was transferred to the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women in New Jersey.[10] According to her attorney Lennox Hinds, Shakur "understates the awfulness of the condition in which she was incarcerated", which included vaginal and anal searches.[179] Hinds argues that "in the history of New Jersey, no woman pretrial detainee or prisoner has ever been treated as she was, continuously confined in a men's prison, under twenty-four-hour surveillance of her most intimate functions, without intellectual sustenance, adequate medical attention, and exercise, and without the company of other women for all the years she was in custody".[133]

Shakur was identified as a political prisoner as early as October 8, 1973, by Angela Davis,[180] and in an April 3, 1977, The New York Times advertisement purchased by the Easter Coalition for Human Rights.[181] An international panel of seven jurists were invited by Hinds to tour a number of U.S. prisons, and concluded in a report filed with the United Nations Commission on Human Rights that the conditions of her solitary confinement were "totally unbefitting any prisoner".[182][133] Their investigation, which focused on alleged human rights abuses of political prisoners, cited Shakur as "one of the worst cases" of such abuses and including her in "a class of victims of FBI misconduct through the COINTELPRO strategy and other forms of illegal government conduct who as political activists have been selectively targeted for provocation, false arrests, entrapment, fabrication of evidence, and spurious criminal prosecutions".[62][183] Amnesty International, however, did not regard Shakur as a former political prisoner.[184]

Escape

In early 1979, "the Family", a group of BLA members, began to plan Shakur's escape from prison. They financed this by stealing $105,000 from a Bamberger's store in Paramus, New Jersey.[185] On November 2, 1979, Shakur escaped the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women in New Jersey, when three members of the Black Liberation Army visiting her drew concealed .45-caliber pistols and a stick of dynamite, seized two correction officers as hostages, commandeered a van and (with the assistance of members of the May 19 Communist Organization) made their escape.[186][187] No one was injured during the prison break, including the officers held as hostages who were left in a parking lot.[38] According to later court testimony, Shakur lived in Pittsburgh until August 1980, when she flew to the Bahamas.[185] Mutulu Shakur, Silvia Baraldini, Sekou Odinga, and Marilyn Buck were charged with assisting in her escape; Ronald Boyd Hill was also held on charges related to the escape.[188][189] In part for his role in the event, Mutulu was named on July 23, 1982, as the 380th addition to the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list, where he remained for the next four years until his capture in 1986. State correction officials disclosed in November 1979 that they had not run identity checks on Shakur's visitors[190] and that the three men and one woman who assisted in her escape had presented false identification to enter the prison's visitor room,[191] before which they were not searched.[62] Mutulu Shakur and Marilyn Buck were convicted in 1988 of several robberies as well as the prison escape.[192]

At the time of the escape, Kunstler had just started to prepare her appeal.[158] After her escape, Shakur lived as a fugitive for several years. The FBI circulated wanted posters throughout the New York – New Jersey area; her supporters hung "Assata Shakur is Welcome Here" posters in response.[193] In New York, three days after her escape, more than 5,000 demonstrators organized by the National Black Human Rights Coalition carried signs with the same slogan. At the rally, a statement from Shakur was circulated condemning U.S. prison conditions and calling for an independent "New Afrikan" state.[189][194]

For years after Shakur's escape, the movements, activities and phone calls of her friends and relatives—including her daughter walking to school in upper Manhattan—were monitored by investigators in an attempt to ascertain her whereabouts.[195] In July 1980, FBI director William H. Webster said that the search for Shakur had been frustrated by residents' refusal to cooperate, and a New York Times editorial opined that the department's commitment to "enforce the law with vigor—but also with sensitivity for civil rights and civil liberties" had been "clouded" by an "apparently crude sweep" through a Harlem building in search of Shakur.[196] In particular, one pre-dawn April 20, 1980, raid on 92 Morningside Avenue, during which FBI agents armed with shotguns and machine guns broke down doors and searched through the building for several hours while preventing residents from leaving, was seen by residents as having "racist overtones".[197] In October 1980, New Jersey and New York City Police denied published reports that they had declined to raid a Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn building where Shakur was suspected to be hiding for fear of provoking a racial incident.[198] Since her escape, Shakur has been charged with unlawful flight to avoid imprisonment.[199]

Political asylum in Cuba

Shakur was in Cuba by 1984; in that year she was granted political asylum there.[193] The Cuban government paid approximately $13 a day toward her living expenses.[195][200] In 1985, her daughter, Kakuya, who had been raised by Shakur's mother in New York, came to live with her. In 1987, her presence in Cuba became widely known when she agreed to be interviewed by Newsday.[12][10][201]

In an open letter, Shakur has called Cuba "One of the Largest, Most Resistant and Most Courageous Palenques (Maroon Camps) that has ever existed on the Face of this Planet".[202] She has praised Fidel Castro as a "hero of the oppressed"[12] and referred to herself as a "20th century escaped slave".[202] Shakur is also known to have worked as an English-language editor for Radio Havana Cuba.[203]

Books

In 1987, she published Assata: An Autobiography, which was written in Cuba. Her autobiography has been cited in relation to critical legal studies[204] and critical race theory.[205] The book does not give a detailed account of her involvement in the BLA or the events on the New Jersey Turnpike, except to say that the jury "[c]onvicted a woman with her hands up!"[44][78] It gives an account of her life beginning with her youth in the South and New York. Shakur challenges traditional styles of literary autobiography and offers a perspective on her life that is not easily accessible to the public.[206][207] The book was published by Lawrence Hill & Company in the United States and Canada but the copyright is held by Zed Books Ltd. of London due to "Son of Sam" laws, which restrict who can receive profits from a book.[208] In the six months preceding the publications of the book, Evelyn Williams, Shakur's aunt and attorney, made several trips to Cuba and served as a go-between with Hill.[201] Her autobiography was republished in Britain in 2014[129] and a dramatized version performed on BBC Radio 4 in July 2017.[209]

In 1993, she published a second book, Still Black, Still Strong, with Dhoruba bin Wahad and Mumia Abu-Jamal.

In 2005, SUNY Press released The New Abolitionists (Neo)Slave Narratives and Contemporary Prison Writings, edited and with an added introduction by Joy James, in which Shakur's Women in Prison: How We Are 1978 is featured.[210]

Extradition attempts

In 1997, Carl Williams, the superintendent of the New Jersey State Police, wrote a letter to Pope John Paul II asking him to raise the issue of Shakur's extradition during his talks with President Fidel Castro.[211] During the pope's visit to Cuba in 1998, Shakur agreed to an interview with NBC journalist Ralph Penza.[212] Shakur later published an extensive criticism of the NBC segment, which inter-spliced footage of Trooper Foerster's grieving widow with an FBI photo connected to a bank robbery of which Shakur had been acquitted.[213] On March 10, 1998[214] New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman asked Attorney General Janet Reno to do whatever it would take to return Shakur from Cuba.[215] Later in 1998, U.S. media widely reported claims that the United States State Department had offered to lift the Cuban embargo in exchange for the return of 90 U.S. fugitives, including Shakur.[216]

The United States Congress passed a non-binding resolution in September 1998, asking Cuba for the return of Shakur as well as 90 fugitives believed by Congress to be residing in Cuba; House Concurrent Resolution 254 passed 371–0 in the House and by unanimous consent in the Senate.[217][218] The Resolution was due in no small part to the lobbying efforts of Governor Whitman and New Jersey Representative Bob Franks.[123] Before the passage of the Resolution, Franks stated: "This escaped murderer now lives a comfortable life in Cuba and has launched a public relations campaign in which she attempts to portray herself as an innocent victim rather than a cold-blooded murderer."[123]

In an open letter to Castro, chair of the Congressional Black Caucus Representative Maxine Waters of California later explained that many members of the Caucus (including herself) were against Shakur's extradition but had mistakenly voted for the bill, which was placed on the accelerated suspension calendar, generally reserved for non-controversial legislation.[219] In the letter, Waters explained her opposition, calling COINTELPRO "illegal, clandestine political persecution".[219]

On May 2, 2005, the 32nd anniversary of the Turnpike shootings, the FBI classified her as a domestic terrorist, increasing the reward for assistance in her capture to $1 million,[193][220] the largest reward placed on an individual in the history of New Jersey. New Jersey State Police superintendent Rick Fuentes said "she is now 120 pounds of money."[221] The bounty announcement reportedly caused Shakur to "drop out of sight" after having previously lived relatively openly (including having her home telephone number listed in her local telephone directory).[222]

New York City Councilman Charles Barron, a former Black Panther, has called for the bounty to be rescinded.[223] The New Jersey State Police and Federal Bureau of Investigation each still have an agent officially assigned to her case.[224] Calls for Shakur's extradition increased following Fidel Castro's transfer of presidential duties;[222] in a May 2005 television address, Castro had called Shakur a victim of racial persecution, saying "they wanted to portray her as a terrorist, something that was an injustice, a brutality, an infamous lie."[225] In 2013, the FBI announced it had added Shakur to its list of 'most wanted terrorists', the first time that a woman was so designated. The reward for her capture and return was also doubled to $2 million.[226]

In June 2017, President Donald Trump gave a speech "cancelling" the Cuban thaw policies of his predecessor Barack Obama. A condition of making a new deal between the United States and Cuba is the release of political prisoners and the return of fugitives from justice. Trump specifically called for the return of "the cop-killer Joanne Chesimard".[227]

Cultural influence

A documentary film about Shakur, Eyes of The Rainbow, written and directed by Cuban filmmaker Gloria Rolando, appeared in 1997.[10] The official premiere of the film in Havana in 2004 was promoted by Casa de las Américas, the main cultural forum of the Cuban government.[203] Assata aka Joanne Chesimard is a 2008 biographical film directed by Fred Baker. The film premiered at the San Diego Black Film Festival and starred Assata Shakur herself. The National Conference of Black Lawyers and Mos Def are among the professional organizations and entertainers to support Assata Shakur; the "Hands Off Assata" campaign is organized by Dream Hampton.[221]

Numerous musicians have composed and recorded songs about her or dedicated to her:

- Common recorded "A Song for Assata" on his album Like Water for Chocolate (2000) after traveling to Havana to meet with Shakur personally.[228]

- Nas listed her name in the booklet of his album Untitled, among important black figures who inspired the album.[229]

- Paris ("Assata's Song", in Sleeping with the Enemy, 1992)

- Public Enemy ("Rebel Without A Pause" in It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, 1988)

- 2Pac ("Words of Wisdom" in 2Pacalypse Now (1991)

- Digital Underground ("Heartbeat Props" in Sons of the P, 1991)

- The Roots ("The Adventures in Wonderland" in Illadelph Halflife, 1996)

- Piebald ("If Marcus Garvey Dies, Then Marcus Garvey Lives" in If It Weren't for Venetian Blinds, It Would Be Curtains for Us All, 1999)

- Asian Dub Foundation ("Committed to Life" in Community Music, 2000)

- Saul Williams ("Black Stacey" in Saul Williams, 2004)

- Rebel Diaz ("Which Side Are You On?" in Otro Guerrillero Mixtape Vol. 2, 2008)

- Lowkey ("Something Wonderful" in Soundtrack to the Struggle, 2011)

- Dead Prez ("I Have A Dream, Too" in RBG: Revolutionary But Gangsta, 2004)

- Murs ("Tale of Two Cities" in The Final Adventure, 2012)

- Jay Z ("Open Letter Part II" in 2013)

Digable Planets, The Underachievers and X-Clan have also recorded songs about Shakur.[189] Shakur has been described as a "rap music legend"[222] and a "minor cause celebre".[230]

On December 12, 2006, the Chancellor of the City University of New York, Matthew Goldstein, directed City College's president, Gregory H. Williams, to remove the "unauthorized and inappropriate" designation of the "Guillermo Morales/Assata Shakur Community and Student Center," which was named by students in 1989. A student group won the right to use the lounge after a campus shutdown over proposed tuition increases.[231] CUNY was sued by student and alumni groups after removing the plaque.[232] As of April 7, 2010, the presiding judge has ruled that the issues of students' free speech and administrators' immunity from suit "deserve a trial".[233]

Following controversy, in 1995, Borough of Manhattan Community College renamed a scholarship that had previously been named for Shakur.[234] In 2008, a Bucknell University professor included Shakur in a course on "African-American heroes"—along with figures such as Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, John Henry, Malcolm X, and Angela Davis.[235] Her autobiography is studied together with those of Angela Davis and Elaine Brown, the only women activists of the Black Power movement who have published book-length autobiographies.[236] Rutgers University professor H. Bruce Franklin, who excerpts Shakur's book in a class on 'Crime and Punishment in American Literature,' describes her as a "revolutionary fighter against imperialism".[237]

Black NJ State Trooper Anthony Reed (who has left the force) sued the police force because, among other things, persons had hung posters of Shakur, altered to include Reed's badge number, in a Newark barracks. He felt it was intended to insult him, as she had killed an officer, and was "racist in nature".[238] According to Dylan Rodriguez, to many "U.S. radicals and revolutionaries" Shakur represents a "venerated (if sometimes fetishized) signification of liberatory desire and possibility".[239]

The largely Internet-based "Hands Off Assata!" campaign is coordinated by Chicago-area Black Radical Congress activists.[240]

In 2015, New Jersey's Kean University dropped hip-hop artist Common as a commencement speaker because of police complaints. Members of the State Troopers Fraternal Association of New Jersey expressed their anger over Common's "A Song For Assata".[241]

In 2015, Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza writes: "When I use Assata's powerful demand in my organizing work, I always begin by sharing where it comes from, sharing about Assata's significance to the Black Liberation Movement, what its political purpose and message is, and why it's important in our context."[242]

The Chicago Black activist group Assata's Daughters is named in her honor.[243] In April 2017, former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick's foundation donated $25,000 to the group. [244]

In July 2017, the Women's March official Twitter feed celebrated Shakur's birthday, leading to criticism from some media outlets.[245][246][247]

In April 2018, a North Carolina court ordered that payment of $15,000 be made to Shakur's representative, her sister Beverly Goins, as part of a land deal.[248]

Notes

- The Federal Bureau of Investigation notes that Shakur has also used August 19, 1952, as her birthdate.[1]

- Note that the New York Times source given here reverses the roles of Zayd Shakur and Acoli.

References

- "Most Wanted Terrorists". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- "Cuba still harbors one of America's most wanted fugitives. What happens to Assata Shakur now? - The Washington Post". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- "Joanne Chesimard Reward Poster" (PDF). Official Site of the State of New Jersey.

- "Black Liberation Army: Understanding - Monitoring - Controlling". Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- "Joanne Chesimard First Woman Named to Most Wanted Terrorists List". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- "JOANNE DEBORAH CHESIMARD". Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- Mueller, Robert S. III. "Wanted by the FBI – Fugitive – Joanne Deborah Chesimard". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2008. According to the FBI, Shakur has also used August 19, 1952, as a birthdate.

- Castellucci, John (1986). The Big Dance: the untold story of Kathy Boudin and the terrorist family that committed the Brink's robbery murders. Dodd, Mead. ISBN 9780396087137.

- Eyes of the Rainbow. Dir. Gloria Roland. Perf. Asset Shakur. 1997. May 4, 2013. Accessed May 15, 2017.

- Scheffler, 2002, p. 203.

- Gates, Henry Louis; Anthony Appiah (1999). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Basic Civitas Books. pp. 1697–1698. ISBN 0-465-00071-1.

- Howell, Ron (October 11, 1987) "'On the Run With Assata Shakur' - Newsday.

- Shakur, Assata (1987). Assata: An Autobiography. Zed Books. ISBN 9781556520747.

- "Hands Off Assata Shakur: Angela Davis Calls for Radical Activism to Protect Activist Exiled in Cuba", Democracy Now! Accessed May 16, 2017.

- Williams, 1993, p. 7.

- Perkins, 2000, p. 103.

- James, Matthew Thomas; James, Joy James, eds. (2005). The New Abolitionists: (Neo)slave Narratives And Contemporary Prison Writings. SUNY Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-7914-6485-7.

- "Gale - Product Login". galeapps.galegroup.com. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- Shakur, 1987, p. 221-4.

- Finkelman, Paul (2009). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century Five-volume Set. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780195167795.

- Harris, Paul (May 3, 2013). "FBI makes Joanne Chesimard the first woman to appear on most-wanted list". The Guardian.

- James, Joy (2003). Imprisoned Intellectuals: America's Political Prisoners Write on Life, Liberation, and Rebellion. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 104. ISBN 0-7425-2027-7.

- Van Deburg; William L. (1997). Modern Black Nationalism: From Marcus Garvey to Louis Farrakhan. NYU Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-8147-8789-4.

- Shakur, Assata. Assata - an autobiography. London: Zed, 2014. Print.

- Waggoner, Walter H. (April 7, 1971). "Woman Shot in Struggle With Her Alleged Victim". The New York Times. p. 40. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- The New York Times (November 23, 1977), "Plea by Joanne Chesimard", p. 23.

- Seedman, Albert and Peter Hellman. (1975) Chief!. Avon ISBN 0-380-00358-9. pp. 451–452.

- Williams, 1993, pp. 4–5.

- "2 Suspects Named In Grenade Attack". The New York Times. December 22, 1971. p. 23.

- Pace, Eric (December 27, 1971). "Police See More Military Arms in Use", The New York Times, p. 10.

- The New York Times (January 1, 1972). "A Suspect in Panther's Death Here Is Slain by F.B.I. in South", p. 6.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (February 9, 1972), "9 in Black 'Army' Are Hunted in Police Assassinations", The New York Times, p. 1.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (January 30, 1973). "Police by Hundreds Comb 2 Boroughs for 6 Suspects in Ambush Shootings".

- The New York Times, p. 43.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (May 3, 1973), "Seized Woman Called Black Militants' 'Soul'". The New York Times, p. 47.

- Williams, 1993, p. 5.

- Daly, Michael (December 13, 2006). "The Msgr. & the Militant", New York Daily News.

- Churchill and Vander Wall, 2002, p. 308.

- Churchill and Vander Wall, 2002, p. 409.

- Seedman, Albert A. (1975). Chief!. New York: Avon Books.

- Jones, Robert A. (May 3, 1973), "2 Die in Shootout; Militant Seized", Los Angeles Times, p. 22.

- Camisa, Harry (2003). Inside Out: Fifty Years Behind the Walls of New Jersey's Trenton State Prison. Windsor Press and Publishing. ISBN 0-9726473-0-9, p. 197.

- Williams, 1993, p. 6.

- Burrough, Bryan (2016). Days of Rage: America's Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 9780143107972.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (February 17, 1972). "Evidence of 'Liberation Army' Said to Rise", The New York Times, p. 1.

- McFadden, Robert D. (February 19, 1972). "Warrant Issued In Police Slaying". The New York Times, p. 1.

- Montgomery, Paul L. (February 20, 1972), "3D Suspect Linked To Police Slayings", The New York Times, p. 43.

- Perlmutter, Emanuel (January 29, 1973), "Extra Duty Tours For Police Set Up After 2D Ambush", The New York Times, p. 61.

- McShane, Joseph Stepansky, Thomas Tracy, Larry (March 5, 2015). "Death of cop Richard Rainey could have been due to 1981 shooting, could mean life in jail for shooter Abdul Majid". New York Daily News. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - According to Churchill and Vander Wall (2002): "What had emerged in the 1980s was a formal amalgamation of FBI COINTELPRO specialists and New York City red squad detectives known as the Joint Terrorist Task Force (JTTF), consolidating the more ad hoc models of such an apparatus which had materialized in cities like Chicago and Los Angeles during the late 1960s" (p. 309); "JTTF: The Joint Terrorist Task Force, created in the late 1970s as an interlock between the FBI and New York City red squads to engage in COINTELPRO-type activities" (p. xiii).

- Williams, 1993, p. 3.

"It was the spring of 1973 and for the last two years the nationwide dragnet for her capture had intensified each time a young African American identified as a member of the BLA was arrested or wounded or killed. The Joint Terrorist Task Force, made up of the FBI and local police agencies across the country, issued daily bulletins predicting her imminent apprehension each time another bank had been robbed or another cop had been killed. Whenever there was a lull in such occurrences, they leaked information, allegedly classified as 'confidential,' to the media, repeating past accusations and flashing her face across television screens and newspapers with heartbeat regularity, lest the public forget." - Cleaver and Katsiaficas, 2001, p. 16.

- Cleaver and Katsiaficas, 2001, p. 13.

- Marable, Manning, and Mullings, Leith. (2003). Let Nobody Turn Us Around: Voices of Resistance, Reform, and Renewal: an African American Anthology. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-8346-X. pp. 529–530.

- Zinn, Howard, and Anthony Arnove (2004). Voices of a People's History of the United States. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1-58322-628-1, p. 470.

- O'Reilly, Kenneth (1989), Racial Matters: The FBI's Secret File on Black America, 1960–1972. Collier Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-923681-9.

- Wolf, Paul (2001). "COINTELPRO: The Untold American Story" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2016.

- Sullivan, Joseph F. (May 3 or 4th, 1973). "Panther, Trooper Slain in Shoot-Out", The New York Times, p. 1.

- Waggoner, Walter H. (February 14, 1977). "Jury in Chesimard Murder Trial Listens to State Police Radio Tapes", The New York Times, p. 83.

- Burrough, Bryan (2016). Days of Rage: America's Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 246. ISBN 9780143107972.

- Johnston, Richard J. (February 20, 1974). "Squires Jurors Hear Chase Tape". The New York Times, p. 78.

- Kirsta, Alix (May 29, 1999), "A black and white case – Investigation – Joanne Chesimard", The Times.

- Johnston, Richard J. (February 14, 1974). "Trooper Recalls Shooting on Pike", The New York Times, p. 86. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- Sullivan, Joseph E. (March 25, 1977). "Chesimard Jury Asks Clarification of Assault Charges", The New York Times, p. 50.

- Johnston, Richard J. H. (March 9, 1974). "Jury Deliberations Begin in Murder Trial of Squire", The New York Times, p. 64.

- Johnston, Richard H. (February 13, 1974). "Squire Charged With 'Execution'", The New York Times, p. 84.

- Sullivan, Joseph F. (February 24, 1977), "Chesimard Attorney Acts to Call Kelley; Wants F.B.I. Director and Others to Testify on Program Aimed at Harassing Activists", The New York Times, p. 76, column 1.

- Sullivan, Joseph F. (May 4, 1973). "Gunfight Suspect Caught in Jersey", The New York Times, p. 41.

- Kupendua, Marpessa (January 28, 1998), "Sundiata Acoli", Revolutionary Worker. No. 94. Retrieved on May 9, 2008.

- Sullivan, Joseph F. (March 16, 1977). "Mrs. Chesimard, on Stand, Denies Having Weapon in Turnpike Shooting", The New York Times, p. 57.

- Tomlinson, 1994, p. 144.

- Jones, 1998, p. 397.

- Davis, Angela Yvonne. 2003. Are Prisons Obsolete? Seven Stories Press; ISBN 1-58322-581-1, p. 62.

- Dandridge, Rita B. 1992. Black Women's Blues: A Literary Anthology, 1934–1988. Maxwell Macmillan International; ISBN 0-8161-9084-4, p. 113.

- The New York Times (May 15, 1973). "Miss Chesimard Transferred", p. 83.

- The New York Times (June 5, 1973). "Black Militant Transferred", p. 88.

- Wahad, Dhoruba Bin; et al. (1993). Still Black, Still Strong: Survivors of the U.S. War against Black Revolutionaries. Semiotext(e). pp. 205–206.