Automotive industry in the United States

In the United States, the automotive industry began in the 1890s and, as a result of the size of the domestic market and the use of mass production, rapidly evolved into the largest in the world. The United States was the first country in the world to have a mass market for vehicle production and sales and is a pioneer of the automotive industry[1] and mass market production process.[2][3] During the 20th century, global competitors emerged, especially in the second half of the century primarily across European and Asian markets, such as Germany, France, Italy, Japan and South Korea. The U.S. is currently second among the largest manufacturers in the world by volume.

| Automotive industry in the United States | |

|---|---|

A Ford Model T, built in 1927. Originally released in 1908, it was the first affordable automobile and dominated sales for years. |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Economy of the United States |

|---|

|

American manufacturers produce approximately 10 million units annually.[4] Notable exceptions were 5.7 million automobiles manufactured in 2009 (due to crisis), and more recently 8.8 million units in 2020 due to the global COVID-19 pandemic.[4][5] Production peaked during the 1970s and early 2000s at 13–15 million units.[6][7][8]

Starting with Duryea in 1895, at least 1,900 different companies have been formed, producing over 3,000 makes of American automobiles.[9] World War I (1917–1918) and the Great Depression in the United States (1929–1939) combined to drastically reduce the number of both major and minor producers. During World War II, all the auto companies switched to making military equipment and weapons. By the end of the 1950s the remaining smaller producers disappeared or merged into amalgamated corporations. The industry was dominated by three large companies: General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler, all based in Metro Detroit. Those "Big Three" continued to prosper, and the U.S. produced three-quarters of all automobiles in the world by 1950, 8.0 million out of 10.6 million produced. In 1908, 1 percent of U.S. households owned at least one automobile, while 50 percent did in 1948 and 75 percent did in 1960.[10][11] Imports from abroad were a minor factor before the 1960s.[7][8]

Beginning in the 1970s, a combination of high oil prices and increased competition from foreign auto manufacturers severely affected the US companies. In the ensuing years, the US companies periodically bounced back, but by 2008 the industry was in turmoil due to the aforementioned crisis. As a result, General Motors and Chrysler filed for bankruptcy reorganization and were bailed out with loans and investments from the federal government. June 2014 seasonally adjusted annualized sales were the biggest in history, with 16.98 million vehicles and toppled the previous record of July 2006.[12] Chrysler later merged into Fiat as Fiat Chrysler and is today a part of the multinational Stellantis group. American electric automaker Tesla emerged onto the scene in 2009 and has since grown to be one of the world's most valuable companies, producing around 1/4th of the world's fully-electric passenger cars.

Prior to the 1980s, most manufacturing facilities were owned by the Big Three (GM, Ford, Chrysler) and AMC. Their U.S. market share has dropped steadily as numerous foreign-owned car companies have built factories in the U.S. As of 2012, Toyota had 31,000 U.S. employees, compared to Ford's 80,000 and Chrysler's 71,100.[13]

History

Production

The development of self-powered vehicles was accompanied by numerous technologies and components giving rise to numerous supplier firms and associated industries. Various types of energy sources were employed by early automobiles including steam, electric, and gasoline. Thousands of entrepreneurs were involved in developing, assembling, and marketing of early automobles on a small and local scale. Increasing sales facilitated production on a larger scale in factories with broader market distribution. Ransom E. Olds and Thomas B. Jeffery began mass production of their automobiles. Henry Ford focused on producing an automobile that many middle class Americans could afford.

A patent filed by George B. Selden on 8 May 1879 covered not only his engine but its use in a four-wheeled car. Selden filed a series of amendments to his application which stretched out the legal process, resulting in a delay of 16 years before the patent was granted on 5 November 1895.[15] Selden licensed his patent to most major American automakers, collecting a fee on each car they produced and creating the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers. The Ford Motor Company fought this patent in court, and eventually won on appeal. Henry Ford testified that the patent did more to hinder than encourage development of autos in the United States.[16]

Originally purchased by wealthy individuals, by 1916 cars began selling at $875. Soon, the market widened with the mechanical betterment of the cars, the reduction in prices, as well as the introduction of installment sales and payment plans. During the period from 1917 to 1926, the annual rate of increase in sales was considerably less than from 1903 to 1916. In the years 1918, 1919, 1921, and 1924 there were absolute declines in automotive production. The automotive industry caused a massive shift in the industrial revolution because it accelerated growth by a rate never before seen in the U.S. economy. The combined efforts of innovation and industrialization allowed the automotive industry to take off during this period and it proved to be the backbone of United States manufacturing during the 20th century.[17]

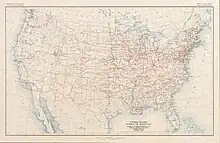

American road system

The practicality of the automobile was initially limited because of the lack of suitable roads. Travel between cities was mostly done by railroad, waterways, or carriages. Roads were mostly dirt and hard to travel, particularly in bad weather. The League of American Wheelmen maintained and improved roads as it was viewed as a local responsibility with limited government assistance. During this time, there was an increase in production of automobiles coupled with a swell of auto dealerships, marking their growth in popularity.

State involvement

State governments began to use the corvee system to maintain roads, an implementation of required physical labor on a public project on the local citizens. Part of their motivation was the needs of farmers in rural areas attempting to transport their goods across rough, barely functioning roads.

The other reason was the weight of the wartime vehicles. The materials involved altered during World War I to accommodate the heavier trucks on the road and were responsible for widespread shift to macadam highways and roadways. However, rural roads were still a problem for military vehicles, so four wheel drive was developed by automobile manufacturers to assist in powering through. As the prevalence of automobiles grew, it became clear funding would need to improve as well, and the addition of government financing reflected that change.

Federal involvement

The Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 allocated $75 million for building roads. It was also responsible for approving a refocusing of military vehicles to road maintenance equipment. It was followed by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, which provided additional funding for road construction. By 1924, there were 31,000 miles of paved road in the U.S.[19]

International trade

|

|

The Big Three automakers

About 3,000 automobile companies have existed in the United States.[20] In the early 1900s, the U.S. saw the rise of the Big Three automakers, Ford, GM, and Chrysler. The industry became centered around Detroit, in Michigan, and adjacent states and in nearby Ontario, Canada. Historian John Rae summarizes the explanations provided by historians: a central geographic location, water access, and an established industrial base with many skilled engineers. The key factor was that Detroit was the base for highly talented entrepreneurs who saw the potential of the automobile: Henry Ford, Ransom E. Olds, Roy D. Chapin, Henry Joy, William C. Durant, Howard E. Coffin, John Dodge and Horace Dodge, and Benjamin Briscoe and Frank Briscoe. From 1900 to 1915 these men transformed the fledgling industry into an international business.[21]

Henry Ford began building cars in 1896 and started his own company in 1903. The Ford Motor Company improved mass-production with the first conveyor belt-based assembly line in 1913, producing the Model T, which had been introduced in 1908. These assembly lines significantly reduced costs. The first models were priced at $850, but by 1924 had dropped to $290. The Model T sold extremely well and Ford became the largest automobile company in the U.S. By the time it was retired in 1927, more than 15 million Model Ts had been sold.

Ford introduced the Model A in 1927, after a six-month production stoppage to convert from the Model T, and produced it to 1931. While the Model A was successful, Ford lost ground to GM and eventually Chrysler, as auto buyers looked to more upscale cars and newer styling. Ford was a pioneer in establishing foreign manufacturing facilities, with production facilities created in England in 1911, and Germany and Australia in 1925. Ford purchased the luxury Lincoln automaker in 1922 and established the Mercury division in 1939.

General Motors Corporation (GM), the company that soon became the world's largest automaker, was founded in 1908 by William Durant. Durant had previously been a carriage maker, and had taken control of Buick in 1904. In 1908, the company initially acquired Buick, Oldsmobile and Oakland (later to become Pontiac). In 1909, GM acquired Cadillac, along with a number of other car companies and parts suppliers. Durant was interested in acquiring Ford, but after initial merger talks, Henry Ford decided to keep his company independent.

In 1910, Durant lost control of GM after over-extending the company with its acquisitions. A group of banks took over control of GM and ousted Durant. Durant and Louis Chevrolet founded Chevrolet in 1913 and it quickly became very successful. Durant began acquiring stock in GM and by 1915 had majority control. Chevrolet was acquired by GM in 1917 and Durant was back in charge of GM. In 1921, Durant was again forced out of the company. During the late 1920s, General Motors overtook Ford to become the largest automaker.

Under the leadership of Alfred P. Sloan, General Motors instituted decentralized management and separate divisions for each price class. They introduced annual model changes. GM became an innovator in technology under the leadership of Charles F. Kettering. GM followed Ford by expanding overseas, including purchasing England's Vauxhall Motors in 1925, Germany's Opel in 1929, and Australia's Holden in 1931. GM established GMAC, now Ally Financial, in 1919 to provide credit for buyers of its cars.

Walter Chrysler was formerly president of Buick and an executive of GM. After leaving GM in 1920, he took control of the Maxwell Motor Company, revitalized the company and, in 1925, reorganized it into Chrysler Corporation. In 1927, he acquired Dodge. The acquisition of Dodge gave Chrysler the manufacturing facilities and dealer network that it needed to significantly expand production and sales. In 1928, Chrysler introduced the Plymouth and DeSoto brands. Chrysler overtook Ford to become the second largest auto maker by the 1930s, following similar strategies as General Motors.

General Motors wanted automobiles to be not just utilitarian devices, which Ford emphasized, but status symbols that were highly visible indicators of an individual's wealth. Through offering different makes and models, they offered different levels in social status, meeting the demands of consumers needing to display wealth. Ford and General Motors each had their own impact on social status and the type of market they were targeting. Henry Ford focused on delivering one inexpensive, efficient product for the masses. Ford's offer was one car, one color, for one price. He manufactured a product for the masses, and provided a $5 daily wage so that there was a local market to buy this product. By contrast, General Motors offered a product that catered to those looking to gain status by having that sense of individualism and offering different make, models, and quality.[22]

Great Depression and World War II

The 1930s saw the demise of many auto makers due to the economic effects of the Great Depression, stiff competition from the Big Three, and/or mismanagement. Luxury car makers were particularly affected by the economy, with companies like Stutz Motor Company, Pierce-Arrow Motor Car Company, Peerless Motor Company, Cunningham, and the Marmon Motor Car Company going out of business.

The 1930s also saw several companies with innovative engineering, such as the Doble Steam Motors Corporation (advanced steam engines) and Franklin Automobile Company (air-cooled aluminium engines) going out of business. Errett Lobban Cord, who controlled the Auburn Automobile Company (which also sold the Cord) and the Duesenberg Motor Company, was under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Internal Revenue Service. His auto empire collapsed in 1937 and production ceased.

Major technological innovations were introduced or were widely adopted during the 1930s, such as synchromesh manual transmissions, semi-automatic transmissions, automatic transmissions, hydraulic brakes, independent front suspension, and overhead-valve engines. The Cord 810 used front-wheel drive, had hidden headlights, and was offered with a supercharger. Exterior styling designs were more flowing, as shown most noticeably on the Auburn Speedster and the Cord 810/812. Radical air-streamed design was introduced on the Chrysler Airflow, a sales flop, and the Lincoln-Zephyr (both of which used unit-body construction). Packard introduced their "Air Cool-ditioned" car in 1940.

After the United States entered World War II in December 1941, all auto plants were converted to war production, including jeeps, trucks, tanks, and aircraft engines. All passenger automobile production ceased by February 1942. The industry received $10 billion in war-related orders by that month, compared to $4 billion before the attack on Pearl Harbor. All factories were enlarged and converted, many new ones such as Ford's Willow Run and Chrysler's Detroit Arsenal Tank Plant were built, and hundreds of thousands more workers were hired.[23]

Many workers were new arrivals from Appalachia. The most distinctive new product was the Jeep, with Willys making 352,000 and Ford another 295,000. The industry produced an astonishing amount of material, including 5.9 million weapons, 2.8 million tanks and trucks, and 27,000 aircraft. This production was a major factor in the victory of the allies.[24] Experts anticipated that Detroit would learn advanced engineering methods from the aviation industry that would result in great improvements for postwar civilian automobiles.[23]

Unionization of the auto manufacturers workforce

Due to the difficult working conditions in the auto production plants, auto workers began to seek representation to help improve conditions and ensure fair pay. The United Automobile Workers union won recognition from GM and Chrysler in 1937, and Ford in 1941. In 1950, the automakers granted workers a company-paid pension to those 65 years old and with 30 years seniority.

In the mid-1950s, the automakers agreed to set up a trust fund for unemployed auto workers. In 1973, the automakers agreed to offer pensions to any worker with 30 years seniority, regardless of age. By then the automakers had also agreed to cover the entire health insurance bill for its employees, survivors, and retirees.

Decline of the independent automakers

The only major auto companies to survive the Great Depression were General Motors Corporation, Ford Motor Company, Chrysler Corporation, Hudson Motor Car Company, Nash-Kelvinator Corporation, Packard Motor Car Company, Studebaker Corporation, and Crosley Motors. The former three companies, known as the Big Three, enjoyed significant advantages over the smaller independent auto companies due to their financial strength, which gave them a big edge in marketing, production, and technological innovation. Most of the Big Three's competitors ended production by the 1960s, and their last major domestic competitor was acquired in the 1980s.

Crosley Motors ceased auto production in 1952. Packard and Studebaker merged in 1954, but ended production of Packard-branded cars in 1958 and ceased all auto production in 1966.

Kaiser-Frazer Corporation was started in 1945 and acquired Willys-Overland Motors (maker of the Jeep) in 1953. Production of passenger cars was discontinued in 1955. In 1970, the company was sold to American Motors Corporation.

In 1954, Nash-Kelvinator and Hudson merged to form American Motors Corporation (AMC). The company introduced numerous product and marketing innovations, but its small size made it difficult to compete with the Big Three and struggled financially. The French auto maker Renault took control of AMC in the early 1980s, but financial difficulties continued and AMC was purchased by Chrysler Corporation in 1987.

Periodically, other entrepreneurs would found automobile companies, but most would soon fail and none achieved major sales success. Some of the best known included Preston Tucker's 1948 sedan, Earl Muntz's Muntz Car Company, Malcolm Bricklin's Bricklin SV-1, the modern Stutz Blackhawk, Clénet Coachworks, Zimmer, Excalibur, and John DeLorean's DeLorean.

Post-war years

Initial auto production after World War II was slowed by the retooling process, shortages of materials, and labor unrest. However, the American auto industry reflected the post-war prosperity of the late-1940s and the 1950s. Cars grew in overall size, as well as engine size during the 1950s. The Overhead valve V-8 engine developed by GM in the late-1940s proved to be very successful and helped ignite the horsepower race, the second salvo of which was Chrysler's 1951 Hemi engine.

Longer, lower, and wider tended to be the general trend. Exterior styling was influenced by jets and rockets as the space-age dawned. Rear fins were popular and continued to grow larger, and front bumpers and taillights were sometimes designed in the shape of rockets. Chrome plating was very popular, as was two-tone paint. The most extreme version of these styling trends were found in the 1959 Cadillac Eldorado and Chrysler Corporation's 1957 Imperial.

The Chevrolet Corvette and the Ford Thunderbird, introduced in 1953 and 1955 respectively, were designed to capture the sports car market. The Thunderbird grew in size in 1958 and evolved into a personal luxury car. The 1950s were also noted for perhaps one of the biggest miscues in auto marketing with the Ford Edsel, which was the result of unpopular styling and being introduced during an economic recession.

The introduction of the Interstate Highway System[25] and the suburbanization of America made automobiles more necessary[26] and helped change the landscape and culture in the United States. Individuals began to see the automobile as an extension of themselves.[27]

1960s

Big changes were taking place in automobile development in the 1960s, with the Big Three dominating the industry. Meanwhile, with the passage of the $33 billion Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, a network of regional and interstate roads continued to enhance transportation. As urban areas became more congested, more families migrated to the suburbs. Between 1960 and 1970, 70 percent of the population's growth occurred in the suburbs.[28]

Imported vehicles grew during the 1950s and 1960s – from a very low base. In 1966, the Big Three (GM, Ford, Chrysler) had market share of 89.6% (44.5% in 2014).[29] From 1966 to 1969, net imports increased at an average annual rate of 84%.[30] The Volkswagen Beetle was the biggest seller.

The compact Nash Rambler had been around since 1950, and American Motors Corporation (AMC) expanded into a range of smaller cars than were offered by the Big Three. By 1960, Rambler was the third most popular brand of automobile in the United States, behind Ford and Chevrolet.[31] In response to this the domestic auto makers developed compact-sized cars, such as the Ford Falcon, Chevrolet Corvair, Studebaker Lark, and Plymouth Valiant.

The four-seat 1958 Ford Thunderbird (second generation) was arguably the first personal luxury car, which became a large market segment.[32]

Pony cars were introduced with the Ford Mustang in 1964. This car combined sporty looks with a long hood, small rear deck, and a small rear seat. The car proved highly successful and imitators soon arose, including the Chevrolet Camaro, Pontiac Firebird, Plymouth Barracuda (actually introduced two weeks prior to the Mustang), AMC Javelin, and the two-seat AMX, as well as the "luxury" version of the Mustang, the Mercury Cougar.

Muscle cars were introduced in 1964 with the Pontiac GTO. These combined an intermediate-sized body with a large high-output engine. Competitors were quickly introduced, including the Chevrolet Chevelle SS, Dodge R/T (Coronet and Charger), Plymouth Road Runner/GTX, Ford Torino, and AMC's compact SC/Rambler. Muscle cars reached their peak in the late-1960s, but soon fell out of favor due to high insurance premiums along with the combination of emission controls and high gas prices in the early 1970s.

While the personal luxury, pony, and muscle cars got most of the attention, the full sized cars formed the bulk of auto sales in the 1960s, helped by low oil prices. The styling excesses and technological gimmicks (such as the retractable hardtop and the pushbutton automatic transmission) of the 1950s were de-emphasized. The rear fins were downsized and largely gone by the mid-1960s, as was the excessive chrome.

Federal regulation of the auto industry

Safety and environmental issues during the 1960s led to stricter government regulation of the auto industry, spurred in part by Ralph Nader and his book: Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-in Dangers of the American Automobile. This resulted in higher costs and eventually to weaker performance for cars in the 1970s, a period known as the Malaise Era of auto design [33] during which American cars suffered from very poor performance.[34]

Seat lap belts were mandated by many states effective in 1962. Under the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966, Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards required shoulder belts for front passengers, front head restraints, energy-absorbing steering columns, ignition-key warning systems, anti-theft steering column/transmission locks, side marker lights and padded interiors starting in 1968.

Beginning in 1972, bumpers were required to be reinforced to meet 5-mph impact standards, a decision that was revised in 1982.[35]

With the Clean Air Act (United States) of 1963 and the Vehicle Air Pollution and Control Act of 1965, emission controls began being instituted in 1968. The use of leaded gasoline began being curtailed in the early 1970s, which resulted in lower-compression engines being used, and thus reducing horsepower and performance. Catalytic converters began being widely used by the mid-1970s.

During his first term as EPA Administrator, William Ruckelshaus spent 60% of his time on the automobile industry, whose emissions were to be reduced 90% under the 1970 Clean Air Act after senators became frustrated at the industry's failure to cut emissions under previous, weaker air laws.[36]

1970s

As bold and confident as the Big Three automakers were in the 1950s and 1960s, the American auto makers in the 1970s and 1980s stumbled badly, going from one engineering, manufacturing, or marketing disaster to another, and this time is often referred to as the Malaise era of American auto design.[34]

By 1969, imports had increased their share of the U.S. auto market with smaller, inexpensive vehicles. Volkswagen sold over 500,000 vehicles, followed by Toyota with over 100,000. In 1986 South Korea entered the American market.[37] In response to this, the domestic auto makers introduced new compact and sub-compact cars, such as the Ford Pinto and Maverick, the Chevrolet Vega, and the AMC Gremlin, Hornet and Pacer. (Chrysler had to make do with importing the Dodge Colt from Mitsubishi Motors and the Plymouth Cricket from their affiliated Rootes Group.) However, design and manufacturing problems plagued a number of these cars, leading to unfavorable consumer perceptions.

GM had a string of miscues starting with the Chevrolet Vega, which developed a reputation for rapidly rusting and having major problems with the aluminium engine.[38]

The problems with Ford's Pinto became nationally famous and Ford's reputation was harmed after media accusations that its fuel system was prone to fire when the car was struck from behind. It was also alleged that Ford knew about this vulnerability but did not design any safeguards in order to save a few dollars per vehicle and that the company rationalized that the cost of lawsuits would be less than the cost of redesigning the car. Historical analysis of the facts don't support the "death trap" reputation attached to the Pinto but the damage to Ford's reputation had been done.[39][40]

Auto sales were hurt by the 1973 oil crisis Arab embargo as the price of gasoline soared. Small fuel-efficient cars from foreign automakers took a sharply higher share of the U.S. auto sales market. Under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act[41] the federal government initiated fuel efficiency standards (known as Corporate Average Fuel Economy, or CAFE) in 1975, effective as of 1978 for passenger cars, and as of 1979 for light trucks.[42][43] For passenger cars, the initial standard was 18 miles per gallon (mpg), and increased to 27.5 mpg by 1985.

General Motors began responding first to the high gas prices by downsizing most of their models by 1977, and lowering their performance. In 1979, the second oil price spike occurred, precipitated by political events in Iran, resulting in the 1979 energy crisis. By 1980, the economy slid into turmoil, with high inflation, high unemployment, and high interest rates. The automakers suffered large operating losses. Chrysler was hurt most severely and in 1979 received a bailout from the federal government in the form of $1.5 billion in loan guarantees. One quick fix was a Detroit-built version of their then-new French (Simca) economy car, the Horizon.[44] As a result of its financial difficulties, Chrysler sold its British and French subsidiaries, Rootes Group and Simca to the French automaker Groupe PSA for $1.

Cadillac damaged their reputation when the four-cylinder Cadillac Cimarron was introduced in 1981 (a gussied-up Chevrolet Cavalier at twice the price) and the "V8-6-4" engine didn't work as advertised.[45] GM's reputation was also damaged when it revealed in 1977 that they were installing Chevrolet engines in Oldsmobiles, and lawsuits from aggrieved Oldsmobile owners followed.[46] Likewise litigation ensued when a trio of diesel engines, designed from gasoline engines and used in GM cars from 1978 to 1985 suffered major problems. Class action lawsuits and efforts from the Federal Trade Commission resulted in buybacks of the cars from GM.[47] Chrysler also suffered damage to its reputation when its compact cars, the Plymouth Volaré and Dodge Aspen, were developed quickly and suffered from massive recalls and poor quality.[48]

1980s

In 1981, Japanese automakers entered into the "voluntary export restraint" limiting the number of autos that they could export to the U.S. to 1.68 million per year.[49] One side effect of this quota was that Japanese car companies opened new divisions through which they began developing luxury cars that had higher profit margins, such as with Toyota's Lexus, Honda's Acura, and Nissan's Infiniti. Another consequence was that the Japanese car makers began opening auto production plants in the U.S. The three largest Japanese auto manufacturers all opened production facilities by 1985. These facilities were opened primarily in the southern states because of financial incentives offered by state governments, access to the nation via the interstate highways, the availability of a large pool of cheaper labor, and the weakness of unions. The Southern states passed right-to-work laws and the UAW failed in its repeated union-organizing efforts at these plants.[50][51]

The Big Three began investing in and/or developing joint manufacturing facilities with several of the Japanese automakers. Ford invested in Mazda as well as setting up a joint facility with them called AutoAlliance International. Chrysler bought stock in Mitsubishi Motors and established a joint facility with them called Diamond-Star Motors. GM invested in Suzuki and Isuzu Motors, and set up a joint manufacturing facility with Toyota, called NUMMI (New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc.).[52]

Despite the financial and marketing upheavals during the 1970s and 1980s, these decades led to technological innovations and/or widespread use of such improvements as disc brakes, fuel injection, electronic engine control units, and electronic ignition. Front-wheel drive became the standard drive system by the late 1980s.

By the mid-1980s, oil prices had fallen sharply, helping lead to the revitalization of the American auto industry. Under the leadership of Lee Iacocca, Chrysler Corporation mounted a comeback after its flirtation with bankruptcy in 1979. The minivan was introduced in the 1984 model year by Chrysler with the Plymouth Voyager and Dodge Caravan, and proved very popular. These vehicles were built on a passenger-car chassis and seated up to seven people as well as being able to hold bulky loads. Chrysler introduced their "K-cars" in the 1980s, which came with front-wheel drive and fuel-efficient OHC engines.

In 1987, Chrysler bought American Motors Corporation, which produced the Jeep. This proved to be excellent timing to take advantage of the sport utility vehicle boom. Ford began a comeback after losses of $3.3 billion in the early 1980s. In 1985, the company introduced the very successful, aerodynamic Taurus. General Motors, under the leadership of Roger Smith, was not as successful as its competitors in turning itself around, and its market share fell significantly.

While Ford and Chrysler were cutting production costs, GM was investing heavily in new technology. The company's attempts at overhauling its management structure and using increased technology for manufacturing production were not successful. Several large acquisitions (Electronic Data Systems and Hughes Aircraft Company) diverted management attention away from their main industry. Ford and Chrysler joined in the acquisition and diversification trend, with Ford buying Jaguar Cars, Aston Martin, The Associates (a finance company), and First Nationwide Financial Corp, a savings and loan company.

Chrysler purchased Lamborghini, an interest in Maserati, and Gulfstream Aerospace jets. GM started the Saturn brand in the late 1980s as a way to retake sales from imported cars. While Saturn initially succeeded, GM later neglected to provide it much support. Around this time GM began development on the General Motors EV1 electric car, which debuted in 1996.

1990s

The 1990s began the decade in a recession, which resulted in weak auto sales and operating losses. The Invasion of Kuwait by Iraq caused a temporary jump in oil prices. The automakers recovered fairly quickly. In the mid-1990s, light truck sales, which included sport utility vehicles, pickup trucks and minivans, began to rise sharply.

Due to the Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards differentiating between passenger cars and light trucks, the automakers were able to sell large and heavy vehicles without fear of the CAFE fines. Low oil prices gave incentives for consumers to buy these gas-guzzling vehicles. The American automakers sold combined, and even separately, millions of pickup trucks and body-on-frame SUVs during this period. Imports such as the Toyota 4Runner, Land Cruiser, Tacoma, and Nissan Pathfinder and Frontier were also popular during this time period.

The automakers also continued their trend of purchasing or investing in foreign automakers. GM purchased a controlling interest in Saab in 1990, Isuzu in 1998 and Daewoo Motors in 2001, and invested in Subaru in 1999 and Fiat in 2000, and also purchased the Hummer name from AM General in 1998. Ford purchased a 33.4 % controlling-interest in Mazda in 1996 and acquired Volvo Cars in 1999 followed by Land Rover in May 2000. GM and Ford also established joint ventures with Chinese auto companies during this period. GM's joint ventures are with Shanghai GM, SAIC-GM-Wuling Automobile, and FAW-GM Light Duty Commercial Vehicle Co Ltd. Ford's joint ventures are with Chang'an Ford and Jiangling Ford.

While the American automakers were investing in or buying foreign competitors, the foreign automakers continued to establish more production facilities in the United States. In the 1990s, BMW and Daimler-Benz opened SUV factories in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, and Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, respectively. In the 2000s, assembly plants were opened by Honda in Lincoln, Alabama, Nissan in Canton, Mississippi, Hyundai in Montgomery, Alabama, and Kia in West Point, Georgia. Toyota opened an engine plant in Huntsville, Alabama, in 2003, along with a truck assembly plant in San Antonio, Texas, and is building an assembly plant in Blue Springs, Mississippi. Volkswagen has announced a new plant for Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Several of the Japanese auto manufacturers expanded or opened additional plants during this period. For example, while new, the Alabama Daimler-Benz and Honda plants have expanded several times since their original construction. The opening of Daimler-Benz plant in the 1990s had a cascade effect. It created a hub of new sub-assembly suppliers in the Alabama area. This hub of sub-assemblies suppliers helped in attracting several new assembly plants into Alabama plus new plants in nearby Mississippi, Georgia and Tennessee.

In 1998, Chrysler and the German automaker Daimler-Benz entered into a "merger of equals" although in reality it turned out be an acquisition by Daimler-Benz. Thus the Big Three American-owned automakers turned into the Big Two automakers. However, a culture clash emerged between the two divisions, and there was an exodus of engineering and manufacturing management from the Chrysler division. The Chrysler division struggled financially, with only a brief recovery when the Chrysler 300 was introduced. In 2007, Daimler-Benz sold the company to a private equity firm, Cerberus Capital Management, thus again making it American-owned.

2000s

The 2000s began with a recession in early 2001 and the effects of the September 11 attacks, significantly affecting auto industry sales and profitability. The stock market decline affected the pension fund levels of the automakers, requiring significant contributions to the funds by the automakers (with GM financing these contributions by raising debt). In 2001, Chrysler discontinued their Plymouth brand, and in 2004 GM ended their Oldsmobile division.

In 2005, oil prices began rising and peaked in 2008. With the American automakers heavily dependent upon the gas-guzzling light truck sales for their profits, their sales fell sharply. Additionally, the finance subsidiaries of the Big Three became of increasing importance to their overall profitability (and their eventual downfall). GMAC (now Ally Financial), began making home mortgage loans, especially subprime loans. With the subsequent collapse of the sub-prime mortgage industry, GM suffered heavy losses.

The Automotive industry crisis of 2008–10 happened when the Big Three were in weak financial condition and the beginning of an economic recession, and the financial crisis resulted in the automakers looking to the federal government for help. Ford was in the best position, as under new CEO Alan Mulally they had fortuitously raised $23 billion in cash in 2006 by mortgaging most of their assets. Chrysler, purchased in 2007 by a private equity firm, had weak financial backing, was the most heavily dependent on light truck sales, and had few new products in their pipeline. General Motors was highly leveraged, also heavily dependent on light truck sales, and burdened by high health care costs.[53]

The CEOs of the Big Three requested government aid in November 2008, but sentiment in Congress was against the automakers, especially after it was revealed that they had flown to Washington, D.C., on their private corporate jets. In December 2008, President Bush gave $17.4 billion to GM and Chrysler from the Troubled Asset Relief Program as temporary relief for their cash flow problems. Several months later, President Obama formed the Presidential Task Force on the Auto Industry to decide how to handle GM and Chrysler. Chrysler received a total of $12.5 billion in TARP funds and entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy in April 2009.

Automaker Fiat was given management control and a 20% ownership stake (adjusted to 35% under certain conditions), the U.S. and Canadian governments were given a 10% holding, and the remaining ownership was given to a Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association (VEBA), which was a trust fund established to administer employee health care benefits.

The Automotive Task Force requested that GM CEO Rick Wagoner resign, and he was replaced by another long-time GM executive, Frederick Henderson. GM received a total of $49.5 billion in TARP funds and entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy in June 2009. The U.S. and Canadian governments received a 72.5% ownership stake, a VEBA received 17.5%, and the unsecured creditors received 10%. As part of the bailout GM and Chrysler closed numerous production plants and eliminated hundreds of dealerships and thousands of jobs. They also required a number of major labor union concessions.[54]

GM sold off the Saab division and eliminated the Pontiac, Hummer, and Saturn Corporation brands. In addition to the $62 billion that the automakers received from TARP, their financing arms, Ally Financial and TD Auto Finance received an additional $17.8 billion.[55] In addition to the funding from the United States government, the Canadian government provided $10.8 billion to GM and $2.9 billion to Chrysler as incentives to maintain production facilities in Canada.[56]

Ford did not request any government assistance, but as part of their downsizing decided in 2009 to sell Volvo Cars, which was acquired by Chinese Geely in the summer of 2010, and phased out their Mercury division in 2011. (Ford had previously sold Aston Martin in 2007, and Land Rover and Jaguar Cars in early-June 2008 and its controlling-interest in Mazda in November 2008). Under the Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program Ford borrowed $5.9 billion to help their vehicles meet higher mileage requirements.

2010s

Ford went through 2012 having recovered to the point of having 80,000 total U.S. employees, supplying their 3,300 dealerships. In comparison, Chrysler had 71,100 U.S. employees supplying their 2,328 dealerships during that year.[13]

Data for the beginning of 2014 put the four companies of GM, Ford, Toyota, and Chrysler, in that order, at the top as having the most U.S. car sales. In terms of specific types of vehicles, the new decade has meant Chrysler having an emphasis on its Ram trucks and the Jeep Cherokee SUV, both of which had "hefty sales" for 2014 according to a news report.[57]

In 2014, Fiat, now named Fiat Chrysler, established full control of ownership of Chrysler and its divisions (Dodge, Jeep and Ram Trucks)

In 2017, it is reported that auto makers spent more on incentives, US$3,830 per vehicle sold, than labour, which is estimated to be less than US$2,500 per vehicle.[58]

In 2017, General Motors sold its European brands, Opel and Vauxhall, to Groupe PSA due to low profits.[59] It also announced the closure of the Holden plant in Australia, making Holden an import brand.[60]

In 2019, General Motors closed 5 plants.[61] It also pulled out of Uzbekistan.[62]

Near the end of the decade, it became clear that the market now has a preference for crossover SUVs over passenger cars.

In 2016, Fiat Chrysler announced that it would be discontinuing the Dodge Dart and Chrysler 200 sedans. CEO Sergio Marchionne said that, even though they were good cars, they were the least financially rewarding investments the company has made recently.[63]

Ford, in 2018, announced that it will be discontinuing all of its passenger cars save for the Ford Mustang, and the Ford Focus would come back as a crossover-hatchback vehicle known as the Ford Focus Active.[64] Ford later cancelled plans of selling the Ford Focus Active in the United States and Canada as a result of the Trump Administration imposing tariffs on all Chinese built vehicles due to China's human rights violations, leading to a China-United States Trade War as the Ford Focus Active for the US and Canadian markets would be imported from the Changan Ford factory in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province, China.[65] General Motors followed by saying it would not follow Ford, however, backtracked on that and announced that it would be discontinuing most of its passenger cars by 2022.

2020s

In 2020, General Motors announced the end of Holden and will leave Australia and New Zealand by 2021.[66] General Motors has also announced its exit from the Thai market and plans to sell their Rayong plant.[67] In August 2021, Ford announced that it would be shutting down its India production as it was not able to have sufficient demand to justify running 2 plants. In January 2021, Fiat Chrysler (FCA) merged with Groupe PSA hence making FCA's North American operations (including Dodge, Chrysler, Jeep and Ram) part of a brand new parent entity named Stellantis, which is headquartered in The Netherlands.

On January 28, 2021, General Motors announced that it will become 100% all-electric by 2035 in order to become compliant with the Biden Administration's tougher automotive emission standards and electric vehicle goals due to worsening climate change and air pollution.[68]

By 2021, the only non-SUV, truck, or van that Ford produced was the Mustang pony car, while GM only produced the Malibu midsized sedan, the Camaro pony car and the luxury Cadillac CT4 and CT5

The late 2010s and early 2020s also saw the rise of electric-only brand Tesla, which became the most valuable automaker in the world by market capitalization in January 2020, and produced over half a million cars in 2020.[69][70]

The decade has also seen the rise of electric cars in general, and in 2020 roughly 2 percent of all new cars sold were fully electric.[71]

According to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, by 2026, all new passenger vehicles sold must be equipped with systems that do not allow the vehicle to turn on if blood alcohol content level is above the amount permissible by law.[72] The legislation is not clear what form this detection would take, the wording states that the monitoring would be "passive" which will possibly require the use of cameras in order to properly track and monitor driver behavior. Proponents of this change state that it will reduce drunk driving deaths on the road while opponents argue that it is a violation of privacy of drivers and that drivers could experience technical difficulties while on the road.[73]

In December 2021, President Joe Biden imposed and signed Executive Order 14057, which states that by 2035, all new light duty vehicles sold in the United States must be 100% all-electric vehicles due to climate change and air pollution issues in the US. The order will also ban new car sales of fossil-fuel powered government-owned vehicles by 2027, new fossil-fuel buses by 2030, and new privately-owned and commercial-owned vehicles by 2035. The order also calls for all government fleets to replace their fossil fuel vehicles with 100% all-electric vehicles by 2035, for all fossil fuel buses to be replaced by 100% all-electric buses by 2040, and for all privately-owned and commercial-owned vehicles to be replaced by 100% all-electric vehicles by 2050.[74][75]

On April 12, 2023, the US Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan proposed tougher automotive emissions standards wherein that 67 percent of all new light-duty highway vehicles sold nationwide must have no tailpipe greenhouse gas emissions by 2032 in order to reduce the probability of severe climate change and its consequences.[76]

See also

- Automotive industry

- Big Three automobile manufacturers

- 1950s American automobile culture

- American automobile industry in the 1950s

- Canada–United States Automotive Products Agreement

- Effects of the 2008–10 automotive industry crisis on the United States

- Good Roads Movement

- History of Chrysler

- History of Ford Motor Company

- History of General Motors

- List of automobile manufacturers of the United States

- List of defunct automobile manufacturers of the United States

- List of automobiles manufactured in the United States

- Passenger vehicles in the United States

Negative effects

- Effects of the car on societies

- Air pollution

- Automobile dependency

- Automobile safety

- Car costs

- Car-free movement

- Compact City

- Congestion pricing

- Environmental impact of transport

- Externalities of automobiles

- Freeway and expressway revolts

- Jaywalking

- Motor vehicle fatality rate in U.S. by year

- New Urbanism

- Roadway noise

- Traffic collision

- Traffic congestion

- Urban decay

- Urban sprawl

Notes

- The Pit Boss (February 26, 2021). "The Pit Stop: The American Automotive Industry Is Packed With History". Rumble On. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- Rae, John Bell. "automotive industry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- "Automobile History". History.com. August 21, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- "Motor vehicle production of the United States and worldwide from 1999 to 2020". statista.com. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- IW Staff (March 26, 2021). "Global Auto Production Dropped 16% Last Year Thanks to COVID-19". Industry Week. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- "2013 production statistics". Oica.net. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- "2017 Production Statistics". International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- Ward's: World Motor Vehicle Data 2007. Wards Communications, Southfield MI 2007, ISBN 0910589534

- Rae(1986), p 6

- Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 217. ISBN 978-0684832838.

- Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1955 (PDF) (Report). Statistical Abstract of the United States (76 ed.). U.S. Census Bureau. 1955. p. 554. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- "U.S. June auto sales hit level not seen since July 2006". Reuters. July 1, 2014.

- O'Dell, John (June 19, 2013). "Foreign Cars Made in America: Where Does the Money Go?". Edmunds.com. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- "Highlights of the Automotive Trends Report". EPA.gov. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). December 12, 2022. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023.

- Selden Road Engine, U.S. patent 549160.pdf Archived 14 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Greenleaf, William. Monopoly on Wheels: Henry Ford and the Selden Automobile Patent. Wayne State University Press, 1951.

- Brungardt, A. O. Book Review:The Automobile Industry: Its Economic and Commercial Development. Ralph C. Epstein. Journal of Business of the University of Chicago, 1, 390–392.

- Bureau of Public Roads; American Association of State Highway Officials (November 11, 1926). United States System of Highways Adopted for Uniform Marking by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). 1:7,000,000. Washington, DC: United States Geological Survey. OCLC 32889555. Retrieved November 7, 2013 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- Hugill, P. J. (1982). "Good Roads and the Automobile in the United States 1880–1929". Geographical Review. 72 (3): 327–349. doi:10.2307/214531. JSTOR 214531.

- Woutat, Donald (January 6, 1985). "High Tech: Auto Makers' History Revisited". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- John B. Rae, "Why Michigan?" Michigan History (1996) 89#2 pp 6–13.

- Katharine Mechler, General Motors: Innovations in American Social Class Structure (2007).

- "U.S. Auto Plants are Cleared for War". Life. February 16, 1942. p. 19. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- Charles K. Hyde, Arsenal of Democracy: The American Automobile Industry in World War II (2013).

- Weingroff, Richard F. (September–October 2000). "The Genie in the Bottle: The Interstate System and Urban Problems, 1939–1957". Public Roads. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. 64 (2). ISSN 0033-3735. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- Vebell, Ed (February 1958). "Popular Mechanics". Popular Mechanics Magazine. Hearst Magazines: 144. ISSN 0032-4558. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- "The Geography of Transport Systems – The Interstate Highway System". Hofstra University. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "1960s: Developing Critical Mass". Nacs50.com. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- Joel Cutcher-Gershenfeld; Dan Brooks; Martin Mulloy (May 6, 2015). "The Decline and Resurgence of the U.S. Auto Industry". Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- Okubo, Sumiye (November 1, 1970). "FOREIGN AUTOMOBILE SALES IN THE UNITED STATES". Economic Quarterly (Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond) : November 1970. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- Flory Jr., J. "Kelly" (2004). American Cars, 1960–1972: Every Model, Year by Year. McFarland. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-7864-1273-0.

- Genat, Robert (2006). Hemi Muscle. Motorbooks. p. 62. ISBN 9780760326787. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Rood, Eric (March 20, 2017). "Tonnage: 10 Gigantic Malaise-Era Land Yachts". Roadkill. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- Stewart, Ben (September 10, 2012). "Performance Pretenders: 10 Malaise-Era Muscle Cars". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- Solomon, Jack (March 1978). "Billion Dollar Bumpers". Reason.

- EPA Alumni Association: EPA Administrator William Ruckelshaus in a 2013 interview discusses his extensive engagement in regulating the U.S. automobile industry as he implemented the Clean Air Act of 1970, Video, Transcript (see pages 14–16).

- R. Y. Ebert, and M. Motoney, "Performance of the South Korean automobile industry in the domestic and United States markets." Journal of Research and Creative Studies 1.1 (2007): 12–24 online.

- Huffman, John Pearley (October 19, 2010). "How the Chevy Vega Nearly Destroyed GM". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- Schwartz, Gary T. (1991). "The Myth of the Ford Pinto Case" (PDF). Rutgers Law Review. 43: 1013–1068.

- Lee, Matthew T; Ermann, M. David (February 1999). "Pinto "Madness" as a Flawed Landmark Narrative: An Organizational and Network Analysis". Social Problems. 46 (1): 30–47. doi:10.1525/sp.1999.46.1.03x0240f.

- "Bill Summary & Status – 94th Congress (1975–1976) – S.622 – (Library of Congress)". Thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- Baruch Feigenbaum; Julian Morris. "CAFE Standards in Plain English" (PDF). Reason.

- "A Brief History of US Fuel Efficiency Standards Where we are—and where are we going?". The Union of Concerned Scientists is a national nonprofit organization founded more than 50 years ago by scientists and students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. July 25, 2006.

- Bickley, James M. (December 8, 2008). "Chrysler Corporation Loan Guarantee Acto of 1979: Background, Provisions, and Cost". Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- "The 50 Worst Cars Of All Time". Time. September 7, 2007. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007.

- "594 F.2d 1106". Archived from the original on May 14, 2010. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- "The Saga Of The G.M. Diesel: Lemons, Lawsuits And Soon An F.T.C.; Decision". The New York Times. March 27, 1983.

- Huffman, John Pearley (February 12, 2010). "5 Most Notorious Recalls of All Time". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- Barbara A. Sousa, Regulating Japanese Automobile Imports: Some Implications of the Voluntary Quota System, 5 British Columbia International and Comparative Law Review (1982) pp 431+.

- Thomas H. Klier, and James M. Rubenstein, "The changing geography of North American motor vehicle production." Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3.3 (2010): 335–347. online

- Kim Hill, and Emilio Brahmst, "The auto industry moving south: An examination of trends." Center for Automotive Research 15 (2003) online.

- Thomas W. Zeiler, "Business Is War in US-Japanese Economic Relations, 1977–2001." in Partnership: The United States and Japan 1951–2001 ed. by Akira Irike and Robert Wampler, (2001) pp: 223–48.

- Vlasic, Bill; Bunkley, Nick (October 25, 2008). "How the SUV boom drove GM down". HeraldTribune.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- www.gao.gov (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20120106024420/http://www.gao.gov/assets/320/318151.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 6, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - www.gao.gov (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20120106024420/http://www.gao.gov/assets/320/318151.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 6, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - McClearn, Matthew (June 9, 2011). "Autopilot bailout". Canadian Business. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- "Chrysler Shows 13 Percent Increase In March U.S. Auto Sales". Fox Business. April 1, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- Roberts, Adrienne (March 3, 2017). "Keeping the motor running is getting more expensive". The Australian. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- Snavely, Brent (March 6, 2017). "GM selling European brands Vauxhall-Opel to Peugeot". Toronto Star. Toronto Star. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Fabricatorian, Shant (December 12, 2013). "GM to Shutter Holden Production Operations in Australia by 2018". Car and Driver. Car and Driver.

- Putre, Laura. "GM to Close 4 U.S. Plants, 1 in Canada". Industry Week. Industry Week. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "General Motors completes pull out of GM Uzbekistan, company renamed UZAUTO". BNE Intellinews. BNE Intellinews. July 5, 2019. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Stocksdale, Joel. "Marchionne says the Chrysler 200 and Dodge Dart were terrible investments for FCA". Autoblog. Autoblog. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Boshouwers, Derek. "FORD TO STOP PRODUCING CARS HERE BY 2020, EXCEPT FOR MUSTANG AND UPCOMING FOCUS ACTIVE CROSSOVER WILL SURVIVE". auto123.com. auto123. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Ford Won't Build Now-Dead Focus Active Crossover in U.S. To Avoid Tariffs". September 10, 2018.

- Beresford, Colin (February 18, 2020). "Legendary Holden Brand Is Dead as GM Leaves Australia after 89 Years". Car and Driver. Car and Driver. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- MAIKAEW, PIYACHART. "GM to withdraw from Thailand this year". Bangkok Post. Bangkok Post. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Boudette, Neal E.; Davenport, Coral (January 28, 2021). "G.M. Will Sell Only Zero-Emission Vehicles by 2035". The New York Times.

- Isidore, Chris (January 10, 2020). "Tesla is now the most valuable US automaker ever". CNN.com. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- Boudette, Neal E. (January 2, 2021). "Tesla Says It Hit Goal of Delivering 500,000 Cars in 2020". The New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- Kusnetz, Nicholas (December 21, 2020). "Was 2020 The Year That EVs Hit it Big? Almost, But Not Quite". Inside Climate News. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- "H. R. 3684" (PDF). p. 1067. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- "Buried in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill: In-Car Breathalyzers". August 3, 2021.

- "Executive Order on Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal Sustainability". December 8, 2021.

- Shepardson, David; Klayman, Ben (December 8, 2021). "U.S. Government to end gas-powered vehicle purchases by 2035 under Biden order". Reuters.

- Newburger, Emma (April 12, 2023). "Biden proposes toughest auto emissions rules yet to dramatically boost EV sales". CNBC. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

References

- Burgess-Wise, David; Wright, Nicky (1980). Classic American Automobiles. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-454-7.

- Coffey, Frank; Layden, Joseph (1996). America on Wheels: The First 100 Years: 1896-1996. Los Angeles: General Pub. Group. ISBN 1-881649-80-6.

- Collier, James L. (2006). The Automobile. New York: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark. ISBN 0-7614-1877-6.

- Crabb, A. Richard (1969). Birth of a Giant: The Men and Incidents That Gave America the Motorcar. Philadelphia: Chilton Book Co. OCLC 567965259.

- Georgano, G. N.; Wright, Nicky (1992). The American Automobile: A Centenary, 1893–1993. New York: Smithmark. ISBN 0-8317-0286-9.

- Mechler, Katharine (2007) General Motors: Innovations in American Social Class Structure

- Peterson, J. S. (1987). Auto Work. American automobile workers, 1900-1933 (). Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Rae, John B. "Why Michigan?" Michigan History (1996) 89#2 pp 6–13. online pp 1–9

- Hugill, P. J. (1982). Good Roads and the Automobile in the United States 1880–1929. Geographical Review, 72 (3), 327–349.

- Brungardt, A. O. Book Review:The Automobile Industry: Its Economic and Commercial Development. Ralph C. Epstein. Journal of Business of the University of Chicago, 1, 390–392.

- Heitmann, John. The Automobile and American Life. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009

Further reading

- Berry, Steven, James Levinsohn, and Ariel Pakes. "Voluntary export restraints on automobiles: Evaluating a trade policy." American Economic Review 89.3 (1999): 400–430 online.

- Brown, George. "The U.S. Automobile Industry: Will It Survive Increasing International Competition" (U.S. Army War College, 1991) online

- Chandler, Alfred D. ed. Giant enterprise: Ford, General Motors, and the automobile industry; sources and readings (1964) online, includes primary sources.

- Crandall, Robert W. "The effects of US trade protection for autos and steel." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1987 (1987): 271–288 online.

- Feenstra, Robert C. "Voluntary export restraint in US autos, 1980–81: quality, employment, and welfare effects." in The structure and evolution of recent US trade policy (U of Chicago Press, 1984) pp. 35–66.

- Goldberg, Penny Koujianou. "Trade policies in the US automobile industry." in Japan and the World Economy 6.2 (1994): 175–208.

- Gustin, Lawrence R. "Sights and Sounds of Automotive History" Automotive History Review (2010+, Issue 52, pp 4–8. Guide to video and sound archives for clips of pioneers such as Henry Ford, Billy Durant, and Ransom Olds.

- Halberstam, David. The Reckoning (1986) detailed reporting on decline of the auto industry. online; also online review

- Hyde, Charles K. Arsenal of Democracy: The American Automobile Industry in World War II (2013) excerpt

- Ingrassia, Paul, and Joseph B. White. Comeback: the fall and rise of the American automobile industry (1994) online

- Jeal, M. "Mass confusion: The beginnings of the volume-production of motorcars." Automotive History Review 54 (2012): 34–47.

- Katz, Harry C. Shifting gears : changing labor relations in the U.S. automobile industry (1985) online

- Kennedy, Edward D. The automobile industry; the coming of age of capitalism's favorite child (1941) online

- May, George S. ed. The Automobile industry, 1920–1980 (1989) online

- Minchin, Timothy J. America's Other Automakers: A History of the Foreign-Owned Automotive Sector in the United States (University of Georgia Press, 2021)

- Rae, John B. The American automobile industry (1984), short scholarly survey online

- Rae, John B. The road and the car in American life (1971) online

- Rao, Hayagreeva. "Institutional activism in the early American automobile industry." Journal of Business Venturing 19.3 (2004): 359–384.

- Rubenstein, James M. The Changing U.S. Auto Industry: A Geographical Analysis (Routledge, 1992)

- Seltzer, Lawrence H. A financial history of the American automobile industry; a study of the ways in which the leading American producers of automobiles have met their capital requirements (1928; reprinted 1973) online

- Smitka, Michael. "Foreign policy and the US automotive industry: by virtue of necessity?." Business and Economic History 28.2 (1999): 277–285 online.

- White, Lawrence. The Automobile Industry since 1945 (Harvard UP, 1971) online.

- Wilkins, Mira, and Frank Ernest Hill. American business abroad: Ford on six continents (Cambridge UP, 2011).

- Yates, Brock W. The decline and fall of the American automobile industry (1983) online

Companies

- Cray, Ed. Chrome Colossus: General Motors and Its Time (1980) online detailed popular history.

- Drucker, Peter F. Concept of the corporation (1946, reprinted in 1964) online, based on General Motors

- Farber, David. Sloan Rules: Alfred P. Sloan and the Triumph of General Motors (U of CHicago Press, 2002)

- Hyde, Charles K. Riding the Roller Coaster: A History of the Chrysler Corporation (Wayne State UP, 2003).

- Hyde, Charles K. The Dodge Brothers: The Men, the Motor Cars, and the Legacy (Wayne State UP, 2005).

- Hyde, Charles K. Storied Independent Automakers: Nash, Hudson, and American Motors (Wayne State UP, 2009).

- Langworth, Richard M. The complete history of General Motors, 1908–1986 (1986) online

- Nevins, Allan. Ford: the Times, the Man, the Company (vol 1 1954) online

- Nevins, Allan, and Frank Hill. Ford: Expansion and Challenge 1915–1933 (vol 2, 1957) online

- Nevins, Allan. Ford: Decline and rebirth, 1933–1962 (vol 3, 1963) online

- Pound, Arthur. The turning wheel: The story of General Motors through twenty-five years, 1908–1933 (1934) online free

- Sloan, Alfred P. My Years with General Motors (1964) online

- Tedlow, Richard S. "The Struggle for Dominance in the Automobile Market: the Early Years of Ford and General Motors" Business and Economic History 1988 17: 49–62. Ford stressed low price based on efficient factories but GM did better in oligopolistic competition by including investment in manufacturing, marketing, and management