Spiranthes spiralis

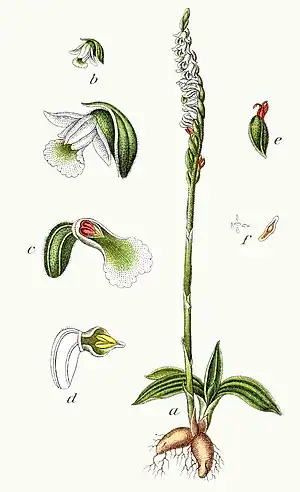

Spiranthes spiralis, commonly known as autumn lady's-tresses,[1] is an orchid that grows in Europe and adjacent North Africa and Asia. It is a small grey-green plant. It forms a rosette of four to five pointed, sessile, ovate leaves about 3 cm (1.2 in) in length. In late summer an unbranched stem of about 10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in) tall is produced with approximately four sheath-shaped leaves. The white flowers are about 5 mm (0.20 in) long and have a green spot on the lower lip. They are arranged in a helix around the upper half of the stalk. The species is listed in Appendix II of CITES as a species that is not currently threatened with extinction but that may become so. Autumn lady's-tresses are legally protected in Belgium and the Netherlands.

| Autumn lady's-tresses | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Orchidaceae |

| Subfamily: | Orchidoideae |

| Tribe: | Cranichideae |

| Genus: | Spiranthes |

| Species: | S. spiralis |

| Binomial name | |

| Spiranthes spiralis | |

Description

Autumn lady's tresses is a polycarp, perennial, herbaceous plant that remains underground during its dormancy in summer with tubers. The species has thirty chromosomes (2n=30).[2]

Root

Underground there are two to four (or exceptionally six), egg-shaped or ovate-oblong, hard tubers which are usually 1–3 cm (0.39–1.18 in) long and ¾–1½ cm (0.3–0.59 in) in diameter, slightly tapering towards the tip. They are pale brown and smooth with short transparent hairs on the outside. These tubers, as in many orchids, have an earthy musty smell, originating from the mycorrhiza. There are no thick filamentous secondary roots as in many other orchids.[2]

Stem

The plant needs many years to grow large enough (eight years) to produce above-ground parts, and to produce a flowering stalk (another three years). Even then, it mostly flowers once every few years, and will during hard times not surface at all. The stem is greyish green, usually 7–20 cm (2.8–7.9 in) (in Southern Europe exceptionally 40 cm) high, unbranched, erect, and terete. Especially further up, the stem is covered with short transparent glandular hairs. Below the flowers stand three to seven grayish green, acute leaves that envelop the stem, with membranous edges and three to five veins. Sometimes the withered leaf remains of the rosette of the previous year are still visible at the base of the stem.[2]

Leaf

The new leaves, which appear at the same time or after the flower stem, stand with four to five together in a rosette beside the stem. They are 2–4 cm (0.79–1.57 in) (exceptionally 5½ cm) long and ¾-1¾ cm (0.3-0.69 in) wide, blue-green, very glossy, sessile, oval and have a pointed tip and translucent entire edges. They have three to five keeled veins. Plants in the Mediterranean can be considerably more robust than those in Western and Central Europe.[2]

Inflorescence

The inflorescence is a slender spike of 3–12 cm (1.2–4.7 in) (exceptionally 20 cm) long, with usually ten to twenty-five (rarely as few as six or as many as thirty) flowers. They are set in a single row, usually in a clockwise or counterclockwise spiral winding around the axis, or rarely all to one side.[2]

Flower

Each flower is subtended by a pale green, lanceolate bract. This shelters the base of the flower, tapers, bends toward the tip, has white edges and scattered glandular hairs at the base. They are usually 9–13 mm (0.35–0.51 in) long and 3–5 mm (0.12–0.20 in) wide. The flowers are very small, ± ½ cm (0.2 in), white, and spread a fragrance that is said to by reminiscent of lily of the valley, vanilla or almonds. The flowers produce nectar unlike in many other orchids. The flower has no spur.[3]

Perianth

Outer tepals are oblong-ovate, slightly tapering to a blunt tip, 6–7 mm (0.24–0.28 in) long, white with a light green vein, have a ciliate or very finely serrated edge, and on the outside with little glandular hairs. Inner perianth leaves are white, elongate with a blunt tip, a vein and adhere with the slightly longer upper outer perianth leaf, thereby forming an upward decurved upper lip. The lower lip is pale green with a wide irregular jagged edge of crystal-like transparent white growths, oblong, approximately 4–5 cm (1.6–2.0 in) long and 2½–3 mm (0.10–0.12 in) wide, trough-shaped, rounded and without lobes and at its top bending down. Both lips give the flower as a whole a trumpet shape. The lower lip encloses the column (merger of the stamen and style) at the base, and there are also two white, glossy, round, nectar-secreting glands, each with a ring of papillae around their base. The small column is green.[2]

Fruit and seed

The capsule is 5½-7 mm (0.22-0.27 in) long, 2–4 mm (0.079–0.157 in) or occasionally up to 5 mm (0.20 in) thick, oval shaped, and filled with countless tiny and very lightweight seeds of 0.5–0.6 mm (0.020–0.024 in) long at 0.1 mm (0.0039 in) thick.[2]

Growth cycle

Around the end of August a rosette of leaves appears, which stays green over the winter and dies back in July at the latest. During the following weeks, a flower stalk emerges from the centre of the dead leaf rosette, and during flowering, one or two new rosettes are formed. Autumn lady's tresses blossoms after the summer (August–October). The species is not self-pollinating. The pollination is done by bees and bumblebees. In nature, less than half of the fruit capsules produce seeds. The very fine seeds are dispersed by the wind in October or November. Nevertheless, most seeds will not disperse more than a few dm from the mother plant since the vast majority of new plants are in close vicinity to an adult plant. Autumn lady's tresses spreads primarily through sexual reproduction. However, the plants to a limited extent also propagate vegetatively by the formation of side buds on the underground stem. The new plant forms its own tuber and leaf rosette, and if the old root dies, the connection between the two daughter plants is broken. The plants therefore often occur in small dense groups. An individual plant does not usually flower every year, apparently because the production of seeds takes a lot of effort. Plants do not necessarily appear above ground each year, so that after an absence mature plants suddenly seem to appear out of nowhere.[2]

Differences from other species

The genus Spiranthes contains about forty species, most of which are from North America. Some species are found in Central and South America, in temperate and tropical Asia southward to Australia and New Zealand. In Europe, three species occur in the wild. Besides the autumn lady's tresses, these are the summer lady's tresses S. aestivalis, and the Irish lady's tresses S. romanzoffiana, a mainly North American species that also occurs in Ireland and western Scotland.[2] The autumn lady's tresses is easily distinguished because the two other species have inflorescences that occur earlier during the year (May–July) from a living rosette, with lanceolate leaves rising at an angle and having cream-colored instead of greenish or greyish white flowers. The autumn lady's tresses also resembles the evergreen Goodyera repens (creeping lady's-tresses or dwarf rattlesnake plantain), which has a creeping rhizome rather than tubers. In G. repens the inflorescence emerges from the centre of a rosette of ovate leaves with a pointed tip, and has striking perpendicular connective veins. The flowers are covered in long hairs that are often tipped with tiny droplets.[4]

Taxonomy

In 1753, Carl Linnaeus was the first to correctly describe the species in his Species Plantarum, naming it Ophrys spiralis. In 1827, François Fulgis Chevallier moved it to the genus Spiranthes that had been erected by Louis Claude Richard in 1817. Synonyms include O. autumnalis, Epipactis spiralis, Serapias spiralis, Neottia spiralis, N. autumnalis, Ibidium spirale, Gyrostachys autumnalis, Spiranthes autumnalis and S. glauca.[2] Autumn lady's threshes belongs to a genus with many species in North-America, but only three species occur in Europe.

Phylogeny

Recent DNA-analysis showed that three Eurasian species of Spiranthes are most related to each other, with a clade consisting of S. sinensis and S. aestivalis being the sister group of S. spiralis.[5]

Etymology

The botanical name is derived from the ancient Greek σπεῖρα (speira) "spiral" and ἄνθος (anthos) "flower". The species name spiralis also refers to the placement of the flowers in a spiral.[6]

Distribution and habitat

Range

Autumn lady's tresses occurs in Europe and small adjacent parts of North Africa and Asia. In the west, it occurs from Ireland to Portugal, in the south from Spain including the Balearic Islands, the coastal mountains of Algeria, Italy including Sicily, Greece including Crete, the Mediterranean, Aegean and Black Sea Coasts of Turkey and the Caucasus Mountains, North Iran eastwards to the Western Himalayas. To the North its limit is from northern England, the Netherlands, Denmark and the southern Baltic, Poland to western Ukraine. It is now considered regionally extinct in Denmark,[7] but it has been introduced to the Swedish island of Öland, where it now seems to be established.[8] In Switzerland the most recent locations are around Lake Lucerne, the Rhine Valley near Chur, in the area of Lake Walen and in Ticino. In Italy it is found in the north-east near the sea. In Great Britain and Ireland its northernmost occurrence is on the Isle of Man. It has never been found in Scotland. In Ireland it has a scattered southern distribution north to County Sligo,[9] with the only known colony in Northern Ireland discovered in 2023 in County Down.[10] In Germany, the plant is endangered in Bavaria (Franconian Heights and Franconian Jura) and Hesse, very endangered in Baden-Württemberg (Swabian Jura and foothills of the Alps) and Rhineland-Palatinate, and near extinction in Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. In France, it occurs across the country, except for the regions of Champagne-Ardenne and Lorraine, and the departments of Nord, Aisne, Eure, Bas-Rhin, Val d'Oise and Seine-et-Marne. It is relatively common on the coasts of Brittany and the Provence, and in the valley of the Orne.[11]

The original range of S. spiralis is probably Mediterranean. Only when man created the habitat for this orchid by settling and converting forests to agriculture and animal husbandry, the species could spread to the north (7000 to 4000 BC).

Habitat

It grows in dry grassy places such as meadows, garigue, heaths, and pine woodland, generally on calcareous soils.

Ecology

Autumn lady's tresses may be found on quite different substrates, from weathered chalk and limestone to sand and gravel in dunes and slightly acidic heathlands. Occasionally, it has also been found on clay on sloping sites. It sometimes occurs in lawns, and was reported from the top of a wall in Sicily. Soils need to be low in nitrogen and phosphorus and neither dry nor wet.

The species occurs in different plant communities, most commonly in highly diverse Festuca ovina–Avenula pratensis grasslands that exist because of intense grazing by sheep or rabbits. These grasslands contain grasses, dicots, and mosses in different mixtures. The turf is short, continuous and consist of very small individual plants. Characteristic species that may be abundant in these grasslands in the UK include the grasses Sheep's fescue Festuca ovina, red fescue F. rubra, Quaking-grass Briza media, crested hair-grass Koeleria macrantha and Crested dog's-tail Cynosurus cristatus, the dicots ribwort plantain Plantago lanceolata, Small burnet Poterium sanguisorba ssp. sanguisorba, Common Bird's-foot Trefoil Lotus corniculatus, Common Cat's-ear Hypochaeris radicata, Mouse-ear hawkweed Pilosella officinarum, Rough hawkbit Leontodon hispidus and Dwarf thistle Cirsium acaule, and the moss Pseudoscleropodium purum.

In the Netherlands, the remaining population in an old dune grassland occurs in a community akin to the Botrychio-Polygaletum, where it occurs with Briza media, Glaucous sedge Carex flacca, Broad-leaved thyme Thymus pulegioides, Common milkwort Polygala vulgaris and Fairy flax Linum catharticum.[2]

Root symbiosis

Like most other species of orchids, autumn lady's tresses needs a fungus (or mycorrhiza) to penetrate the seed to enable it to germinate, as the seeds contain no endosperm or other food reserves. After germination, the seed produces a protocorm and is feed by the symbiotic relationship that is formed with is mycorrhiza. The seedlings parasitize actually on the mycorrhiza, which provides both water, minerals and organic compounds. Mature plants also contain mycorrhiza most of the year, but the amount of hyphae fluctuates with a maximum during the fall and winter. Most deeply infiltrated hyphae are digested at the beginning of flowering time, though the outer cell layer of the tuber may still contain living hyphae. New tubers are colonized when they have reached their maximum size. Infiltrated cells contain coils of hyphae of Rhizoctonia-type.[2] Autumn lady's tresses can accommodate several types of fungus in its roots. Some of these mycorrhizal fungi are from genera that also occur in other orchids, such as Ceratobasidium and Rhizoctonia. But there are also fungi present in the tubers that were not known to enter into an endophytic relationship, such as the ascomycete genera Davidiella, Leptosphaeria and Alternaria and the basidiomycete Malassezia. Even fungi that are known to be pathogenic in other plants, such as Fusarium oxysporum and Bionectria ochroleuca can be found in healthy specimens of this orchid, suggesting that it is able to keep such fungi in check.[12]

Pollination

Pollination of autumn lady's tresses is little observed. In the Netherlands the common carder bee (Bombus pascuorum) and red-tailed bumblebee (Bombus lapidarius) are regular visitors. In southern France (Rhône Department) the honeybee also pollinates. The silver Y (Autographa gamma) is also seen to visits the flowers, but attached pollinia have not been observed.[2]

The pollinators land on the lower lip. On the rear part of the lip are two glands that secrete nectar which is collected in small cavities immediately below them. The access to the nectar is very narrow to by the protruding edge of the column and the glands, and will cause the tongue of the bumblebee or bee to tear a membrane that covers the base of the two pollinia. As a result, the bees tongue comes into contact with an adhesive which hardens directly when exposed to the air. When the tongue is retracted the pollinia cling to it. The lip of flowers that is a few day more matured has opened further making access to the nectar gland wider and making the tongue brush past the stigma and deliver the pollen. Such a flower which develops first to release the pollen, and is later adapted to be pollinated is called protandrous.[13]

In 52% of the plants the flowers are arranged counterclockwise, in 39% clockwise and in 9% of the plants the flowers are to one side of the inflorescence. The pollinators always land at bottom of the inflorescence and visit the flowers ever higher up. Most bumblebees have a strong preference for counterclockwise arrangement, fewer for clockwise. It seems that autumn lady's tresses responds to this preference by offering different inflorescence types and thus increases the chances of fertilization.[14]

Conservation

To conserve S. spiralis and improve the establishment of new habitats the hydrology must be just right: not too dry nor too moist. Because the species has little competitive strength, the soil must be moderate poor in nutrients and eutrophication, for example from adjacent farmland, should be avoided. Autumn lady's tresses grow best in a soil that is not acid. Therefore, acidification must be halted, on loamy soils for example by raising the ground watertable slightly, or by removing the acid humus layer. On sandy soil, it is important to retain or restore the small scale relief so that the optimal moisture is present both in dry and in wet years in the field. During flowering should not be mowed or grazed, but mowing and grazing by sheep or cattle outside this period is beneficial to keep the vegetation sufficiently short. Damaging the soil should be avoided. New locations can be created in the vicinity of existing habitats, possibly aided by scattering cuttings from existing locations to encourage establishment.[15]

References

- David Chapman (2008). Exploring the Cornish Coast. Penzance: Alison Hodge. p. 51. ISBN 9780906720561.

- Jacquemyn, Hans; Hutchings, Michael J. (2010). "Biological Flora of the British Isles: Spiranthes spiralis (L.) Chevall. No. 258, List Vasc. Pl. Br. Isles (1992) no. 162, 7, 1". Journal of Ecology. 98 (5): 1253–1267. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01701.x.

- Jaquemyn, Hans; Brys, Rein; Hermy, Martin (2003). "Bestuiving bij orchideeën: Over bloemen en bijen, verleiding en bedrog" (PDF). Natuur.focus (in Dutch). 2 (3): 109–114.

- Van der Meijden, Ruud (2005). Heukels' Flora van Nederland (in Dutch). Groningen/Houten: Wolters-Noordhoff. ISBN 978-90-01-58344-6.

- Dueck, Lucy A.; Aygoren, Deniz; Cameron, Kenneth M. (2014). "A molecular framework for understanding the phylogeny of Spiranthes (Orchidaceae), a cosmopolitan genus with a North American center of diversity". American Journal of Botany. 101 (9): 1551–1571. doi:10.3732/ajb.1400225. PMID 25253714.

- Klaas Dijkstra. "herfstschroeforchis". Wilde Planten in Nederland en België (in Dutch).

- "Skrueaks". Naturbasen (in Danish). Naturbasen APS. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- "Skruvax". Artfakta (in Swedish). SLU Artdatabanken. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- Cotton, D.C.F.; Dunleavy, J. (2009). "Spiranthes spiralis (L.) Chevall. (Autumn Lady's-tresses orchid), with notes on threats to its conservation status". Ir. Nat. J. 30: 70–73.

- "Northern Ireland first as orchid species autumn's lady's-tresses found". BBC News. 3 October 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- "Spiranthes spiralis (L.) Chevall". Tela Botanica.

- Tondello, A.; Vendramin, E.; Villani, M.; Baldan, B.; Squartini, A. (2012). "Fungi associated with the southern Eurasian orchid Spiranthes spiralis (L.) Chevall". Fungal Biology. 116 (4): 543–549. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2012.02.004. PMID 22483052.

- "Herfstschroeforchis - Spiranthes spiralis". Waarneming.nl (in Dutch).

- Gravendeel, Barbara (2009). "In de voetsporen van Charles Darwin" (PDF). FLORON Nieuws (in Dutch). 10: 1.

- STOWA. "Herfstschroeforchis" (PDF). soortprotocollen flora- en faunawet (in Dutch).