Constitution Avenue

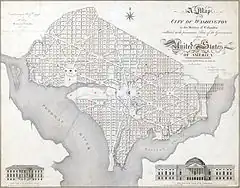

Constitution Avenue is a major east–west street in the northwest and northeast quadrants of the city of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was originally known as B Street, and its western section was greatly lengthened and widened between 1925 and 1933. It received its current name on February 26, 1931, though it was almost named Jefferson Avenue in honor of Thomas Jefferson.[1]

Signage on the 1900 block of Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. | |

| Former name(s) | B Street |

|---|---|

| Maintained by | DDOT |

| Width | 80 feet (24 m) (NW segment) 60 feet (18 m) (NE segment) |

| Location | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| West end | |

| Major junctions | Virginia Avenue NW Massachusetts Avenue NE |

| East end | 21st Street NE |

| Construction | |

| Commissioned | 1791 |

| Completion | 1933 |

Constitution Avenue's western half defines the northern border of the National Mall and extends from the United States Capitol to the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge. Its eastern half runs through the neighborhoods of Capitol Hill and Kingman Park before it terminates at Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. Many federal departmental headquarters, memorials, and museums line Constitution Avenue's western segment.

Creating B Street

When the District of Columbia was founded in 1790, the Potomac River was much wider than it currently is, and a major tidal estuary known as Tiber Creek flowed roughly from 6th Street NW to the shore of the river just south of the White House. In Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's original plan for the city in 1791, B Street NW[2] began at 6th Street NW,[3] and ended at the river's edge at 15th Street NW.[4] Its eastern segment, which was unimpeded by any water obstacles, ran straight to the Eastern Branch river, now known as the Anacostia River. Along its entire length, B Street was 60 feet (18 m) wide.[5]

L'Enfant proposed turning Tiber Creek into a canal. His plan included cutting a new canal south across the western side of the United States Capitol grounds and converting James Creek, which ran from the Capitol south-southwest through the city, into the canal's southern leg.[6] The Washington Canal Company was incorporated in 1802, and after several false starts substantial work began in 1810.[7] The Washington City Canal began operation in 1815.[8] The canal suffered from maintenance problems and economic competition almost immediately. Traffic on the canal was adversely affected by tidal forces, which the builders had not accounted for, which deposited large amounts of sediment in the canal. At low tide, portions of the canal were almost dry.[9] After the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built Washington Branch into the city in 1835,[10] competition from railroads left the canal economically unviable.[11]

Although the Washington City Canal remained in use after the coming of the railroad, by 1855 it had filled with silt and debris to the point where it was no longer functional.[12] It remained in this condition throughout the 1860s.[13] In 1871, Congress abolished the elected mayor and bicameral legislature of the District of Columbia, and established a territorial government. Territorial government only lasted until 1874 when Congress imposed an appointed three-member commission on the city. During this period. the D.C. Board of Public Works enclosed the canal and turned it into a sewer. B Street NW from 15th Street to Virginia Avenue NW was constructed on top of it. Work began in October 1871 and was completed in December 1873.[14]

After terrible flooding inundated much of downtown Washington, D.C., in 1881, Congress ordered the United States Army Corps of Engineers to dredge a deep channel in the Potomac to lessen the chance of flooding. Congress also ordered that the dredged material be used to fill in what remained of the Tiber Creek estuary and build up much of the land near the White House and along Pennsylvania Avenue NW by nearly 6 feet (1.8 m) to form a kind of levee.[15] This "reclaimed land" — which today includes West Potomac Park, East Potomac Park, the Tidal Basin — was largely complete by 1890, and designated Potomac Park by Congress in 1897.[16] Congress first appropriated money for the beautification of the reclaimed land in 1902, which led to the planting of sod, bushes, and trees; grading and paving of sidewalks, bridle paths, and driveways; and the installation of water, drainage, and sewage pipes.[17]

B Street NW extended through the newly created West Potomac Park between Virginia Avenue NW and 23rd Street NW. However, since this area was considered parkland, the street narrowed to just 40-foot (12 m) in width.[5]

B Street reconfiguration and renaming

B Street NW as part of the Arlington Memorial Bridge

On March 4, 1913, Congress created the Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission (AMBC) whose purpose was to design and build a bridge somewhere in West Potomac Park which would link the city to Arlington National Cemetery. But Congress appropriated no money for the design or construction due to the onset of World War I.[18] But after President Warren G. Harding was trapped in a three-hour traffic jam on the Highway Bridge while on his way to dedicate the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier on November 11, 1921, Harding began pushing Congress to move on constructing a new bridge.[19] Congress approved funding for design work on June 12, 1922,[20] and authorized construction of the Arlington Memorial Bridge on February 24, 1925.[21]

The 1925 legislation specified that B Street NW be treated as a major approach to Arlington Memorial Bridge.[22]

Several design problems presented themselves. The first was how to turn B Street NW into a ceremonial gateway. The second was how to link B Street NW with the bridge. This second problem was particularly important, because the Lincoln Memorial stood at the northeastern terminus of the proposed bridge. Third, the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway was being designed to terminate at the Lincoln Memorial as well. The parkway would also interact with the B Street approaches to the bridge.

Additionally, three agencies had design approval over the bridge. The first was the AMBC, which was building it. The second was the National Capital Parks Commission (NCPC), which had statutory authority to approve federal transportation construction in the city. The third was the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), which had to approve any memorial design. Since the bridge was considered a memorial, it also had to pass CFA muster as well.

Connecting, extending, and widening B Street NW

In April 1924, the Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission proposed extending B Street all the way to the U.S. Capitol as part of the plan to turn the street into a major thoroughfare.[23] The NCPC inspected B Street in June 1926,[24] and in August made a preliminary determination that the street should be widened to 72 feet (22 m) between the Potomac River and Virginia Avenue NW. This would be accomplished by moving the south curb south by 20 feet (6.1 m) and the north curb north by 12 feet (3.7 m). But once the street went past Virginia Avenue NW, the NCPC determined that the north curb should not be moved.[5] In September 1926, the NCPC approved widening B Street to 80 feet (24 m) between 6th and 15th Streets NW (by moving the south curb south).[25] This decision was reaffirmed by a joint meeting of the NCPC and the Office of the Supervising Architect of the U.S. Treasury (which was overseeing construction of the Federal Triangle office complex on the north side of B Street between 6th and 15th Streets NW).[26] The NCPC agreed in February 1927 that B Street should extend to Pennsylvania Avenue NW, and was studying whether to extend it through the proposed Senate Park.[3]

Architect William Mitchell Kendall[27][28] proposed creating a traffic circle around the Lincoln Memorial to accommodate the bridge, B Street approach, parkway approach, and Ohio Drive SW approach. The AMBC was dissatisfied with Kendall's design, however, and ordered a major restudy of the B Street connection in December 1926.[4][22]

In May 1927, Kendall presented a revised design for the B Street approach to the Lincoln Memorial traffic circle. The NCPC, concerned with the impending construction of Federal Triangle, worried that a traffic circle would not only fail to accommodate the expected increase in traffic volume but also impair the dignity of the memorial as large numbers of fast-moving automobiles whizzed around it. CFA members did not agree. For example, CFA member James Leal Greenleaf argued that the traffic issue was a red herring; future new bridges over the Potomac would completely alleviate all traffic issues within 50 years, he said.[29]

By September 1927, the NCPC's vision for B Street had expanded. Now the agency saw B Street not just as a gateway but as one of the city's great parade avenues, similar to Pennsylvania Avenue NW.[30]

Connecting B Streets NW and NE

B Street's renewal soon became caught up in the creation of Senate Park north of the United States Capitol building. This area, which today is bounded by Louisiana Avenue NW, Columbus Circle, 1st Street NE, and Constitution Avenue NE/NW, was home to a number of dilapidated office buildings and hotels. But beginning in 1910, Congress began acquiring entire city blocks in this area, with the intent of building an underground parking garage and creating a park between the Capitol and Union Station (which had opened in 1908). The question confronting the AMBC and NCPC was whether B Street should continue east through this area to connect with B Street NE or end at Pennsylvania Avenue NW.

To help plan and develop this area, on April 6, 1928, Congress enacted legislation establishing the Capitol Plaza Commission.[31] On April 19, the Capitol Plaza Commission issued its first preliminary plan for what would become Senate Park. This plan assumed B Street would extend through the park.[32]

In February 1929, the D.C. Department of Roads and Highways finalized its engineering plans to widen B Street NW from 26th Street NW to Pennsylvania Avenue NW.[33] But these plans needed approval of the NCPC as well as funding from Congress. The NCPC discussed the street widening at its March 9 meeting.[34] It made a site visit along the roadway to see how different widths would affect the vista and the grandeur of the planned avenue. The commission agreed that B Street should be extended eastward at least to 3rd Street NW, and that building setbacks should be a minimum of 55 feet (17 m) along the avenue. But the width of the avenue remained in dispute. Tentatively, the NCPC approved a width of 80 feet (24 m) between Pennsylvania Avenue NW and Virginia Avenue NW, and 72 feet (22 m) from Virginia Avenue NW to the Potomac River. It also said that the avenue should be no wider than 72 feet (22 m) from Pennsylvania Avenue NW to 3rd Street NW.[35]

B Street's new name: Constitution Avenue

As the nature of the B Street project became apparent, there were calls to rename the street. In early 1930, legislation was introduced in the House of Representatives to rename the road L'Enfant Avenue. City officials opposed the name, however, advocating instead for Lincoln or Washington avenue.[36] Representative Henry Allen Cooper of Wisconsin subsequently introduced legislation in June 1930 to rename the street Constitution Avenue, a proposal which met with strong approval from the city.[37] Although the House initially rejected the name, the legislation passed both the House and Senate in the second session of the 71st United States Congress.[38] President Herbert Hoover signed the legislation into law on February 25, 1931.[39][40]

The Corps of Engineers realized in the spring of 1930 that no provision had been made for the terminus of B Street. Because this was merely a matter of adding a small traffic circle on the Potomac shoreline and creating a small terrace there, cost-savings elsewhere could provide the funding for the terminus without requiring an additional authorization or appropriation from Congress. The Corps awarded a contract to North Carolina Granite Co. to provide granite for this terrace. Nearly all this granite had arrived by the end of June 1930.[41]

Widening of Constitution Avenue

The city proposed a budget to Congress in May 1930 that included funds to widen B Street NW between 14th and 17th Streets NW. The federal government should pay for 40 percent of the cost of this three-block widening, the city said.[42] When this legislation did not pass during the second session of the 71st Congress, the city proposed in December 1930 a similar funding formula but asked to widen B Street from 14th Street NW all the way to Virginia Avenue.[43] This time Congress approved the legislation.

Widening of what was now called Constitution Avenue NW began at the end of February 1931 with the city finalizing its engineering plans.[44] The city commissioners ordered the $168,500 widening project to begin on May 13, 1931.[45] A small memorial column, marking the point at which water reached inland during the terrible 1889 Potomac River flood, was moved because of the street widening.[46] The CFA, meanwhile, began to study ways to harmonize the treatment of Constitution Avenue NW, the Lincoln Memorial Grounds, and the Arlington Memorial Bridge.[47]

By March 1932, additional funding to complete the widening of Constitution Avenue NW as well as to extend it through Senate Park were still needed.[48] But the House of Representatives declined to approve funding in April 1932.[49]

Funding for this part of the project did not come through until December 1932, when Congress ordered $55,200 transferred from the AMBC budget to the city coffers for this construction. The city came up with another $82,100 to finance its portion of the costs. As part of the funding agreement, the city said it would build only a 72-foot (22 m) wide street between North Capitol Street and 1st Street NW, an 80-foot (24 m) wide street between 1st and 2nd Streets NW, and an 80-foot (24 m) wide street between Pennsylvania Avenue NW and 6th Street NW.[50] But a difficult decision about how to link the two sections of Constitution Avenue NW between 3rd and 6th Streets NW remained. Pennsylvania Avenue NW cut diagonally northwest-to-southeast through these three city blocks, and it was not readily apparent how to handle the crossing so that Constitution Avenue traffic could turn right and left from either direction. The section of the roadway between 6th and 14th Streets NW also remained to be widened. But with the Great Depression worsening, highway construction funds were minimal.

Completing the widening of Constitution Avenue NW

Franklin D. Roosevelt took office as President of the United States in March 1933. Convinced that massive federal spending on public works was essential not only to "prime the pump" of the economy but also to cut unemployment, Roosevelt proposed passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act. The act contained $6 billion in public works spending, which included $400 million for road, bridge, and highway construction. With passage of the act moving forward swiftly, D.C. officials asked Congress on June 12 for the funds to finish widening Constitution Avenue NW.[51] The act passed on June 13, 1933, and Roosevelt signed it into law on June 16. The Public Works Administration (PWA) was immediately established to disburse the funds appropriated by the act. The District of Columbia received a $1.9 million grant for road and bridge construction, and the city said on July 8 it would use a portion of these funds to finish Constitution Avenue.[52] Construction on the $200,000 project was scheduled to begin at the end of August 1933 and employ 150 men.[53]

Part of the PWA grant included funds for the completion of John Marshall Park, at the intersection of 4th Street NW and Pennsylvania Avenue NW. Along with construction of the park, the city finally linked the two ends of Constitution Avenue by turning the western section slightly northward, and the eastern section slightly southward. The one-block section of Pennsylvania Avenue NW between 4th and 5th Streets was renamed Constitution Avenue (leaving Pennsylvania Avenue no longer contiguous). To control these two intersections, 10 traffic signals (some of the first to be installed in downtown D.C.) were placed at these intersections. The intersection opened on August 17, 1933.[54]

The lack of uniform width along Constitution Avenue proved problematic. With little fanfare, the city began widening the entire roadway to 80 feet (24 m). In September 1933, the city received the first disbursement of revenue from the federal gasoline tax. This tax was imposed in the Revenue Act of June 1932. The city used $30,494 in PWA grant money and $45,741 in federal gas tax revenue to widen Constitution Avenue to the full width between North Capitol Street and 2d Street NW. This project, which occurred in conjunction with clearance of Upper Senate Park, began in late September 1933.[55]

City officials also asked the CFA to approve widening of Constitution Avenue to the full width between Virginia Avenue NW and the Potomac River.[56] The CFA quickly approved the project. Paving of the fully widened street began in October 1933 and continued in November.[57] In December, the avenue neared completion with the installation of traffic lights between 6th and 15th Streets NW.[58]

Constitution Avenue terminus

The western terminus of Constitution Avenue is the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge; thus, Constitution Avenue connects the city's ceremonial core with Interstate 66. The eastern terminus is at 21st Street NE, just west of Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. Through traffic is diverted via North Carolina Avenue NE and C Street NE to the Whitney Young Memorial Bridge.

Route numbers

Between Louisiana Avenue and Interstate 66, Constitution Avenue is part of the National Highway System.

Sections of Constitution Avenue are designated U.S. Route 1, U.S. Route 50, or both. Specifically, U.S. 50 runs along the road from its west end to 6th Street NW (eastbound) and 9th Street NW (westbound). U.S. 1 northbound uses the eastbound lanes of Constitution Avenue NW from 14th Street NW to 6th Street NW; southbound U.S. 1 used to run west from 9th Street NW to 15th Street NW but now continues straight through the 9th Street Tunnel to I-395.

Locations of interest along Constitution Avenue

Constitution Avenue NW is bordered by a number of important buildings and attractions. Beginning in the west are several independent federal agencies and institutes, as well as the headquarters of several large associations. These buildings include the United States Institute of Peace Headquarters, the American Institute of Pharmacy, the National Academy of Sciences, the Federal Reserve, the Department of the Interior, and the Organization of American States. The Ellipse, part of the grounds of the President's Park (which includes the White House), also borders the north side of Constitution Avenue NW and forms the boundary between the western and eastern segments of this part of the street. To the east on the north side is Federal Triangle, which contains the headquarters of a number of federal agencies. These include the Department of Commerce, Department of Justice, Environmental Protection Agency, Federal Trade Commission, Internal Revenue Service, and National Archives. The Embassy of Canada and John Marshall Park are located further east of Federal Triangle. Once past Pennsylvania Avenue NW, the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse, George Gordon Meade Memorial, and Department of Labor headquarters, and Senate Park border the north side of the avenue.

On its south side, Constitution Avenue NW is bordered by several monuments and museums. These include Lincoln Memorial, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Constitution Gardens, and the grounds of the Washington Monument. The relocated U.S. Capitol Gatehouses and Gateposts are at Constitution Avenue NW and 15th Street NW. East of the grounds of the Washington Monument are several museums: the National Museum of African American History and Culture (under construction as of 2013), the National Museum of American History, the National Museum of Natural History, National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden, and the National Gallery of Art. Once past the National Gallery of Art, the ground of the United States Capitol border the south side of the avenue.

The north side of Constitution Avenue NE features the Russell, Dirksen, and Hart Senate office buildings. The roadway passes through the Capitol Hill and Kingman Park neighborhoods, and on its south side is bordered by the football stadium of Eastern High School between 17th and 19th Streets NE.

References

- "Why Is It Named Constitution Avenue?". Ghosts of DC. 2012-02-21. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- Cartesian designations such as "Northwest" were not used in the District of Columbia until the 1890s, but for the purposes of this article will be used throughout.

- "Plan Commission to Consider Four Parks Proposals." Washington Post. February 13, 1927.

- "New Study Ordered of Memorial Bridge." Washington Post. December 29, 1926.

- "Park Commission Accepts B Street Boulevard Plans." Washington Post. August 21, 1926.

- Heine, p. 2.

- Heine, p. 5-6.

- Heine, p. 7.

- Heine, p. 10.

- Dilts, p. 184.

- Gutheim and Lee, p. 49-50; Curry, p. 233-234.

- Heine, p. 20-21.

- Heine, p. 23.

- Harrison, p. 253.

- Tindall, p. 396; Gutheim and Lee, p. 94-97; Bednar, p. 47.

- Gutheim and Lee, p. 96-97.

- Report of the Chief of Engineers..., p. 1891. Accessed 2013-04-15.

- Sherrill, p. 21-25 Accessed 2013-04-15.

- Kohler, p. 16.

- "President Urges Funds for Bridge." Washington Post. January 14, 1922; Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission, p. 30.

- "Memorial Bridge Bill Ready for President." Washington Post. February 21, 1925; Weingroff, Richard F. "Dr. S. M. Johnson - A Dreamer of Dreams." Highway History. Office of Infrastructure and Transportation Performance. Federal Highway Administration. U.S. Department of Transportation. April 7, 2011. Accessed 2013-04-15.

- "Grant Is Told Need of Bridge Restudy By Fine Arts Group." Washington Post. December 28, 1926.

- "Bridge to Arlington to Cost $14,750,000 Asked As Memorial." Washington Post. April 10, 1924.

- "Commission Urges Numerous Bathing Pools for Capital." Washington Post. June 20, 1926.

- "B Street to Become 80-Foot Boulevard." Washington Post. September 18, 1926.

- "14-Foot Widening Tentative Traffic Plan for Triangle." Washington Post. December 21, 1926.

- Kendall was the lead designer for the firm designing the bridge, McKim, Mead and White. See: Kohler, p. 17.

- McKim, Mead and White only had responsibility for the architectural features of the bridge. The AMBC turned over engineering aspects of the bridge to the Corps of Engineers on June 29, 1922. See: Christian, William Edmund. "The Arlington Memorial Bridge." Washington Post. November 1, 1925.

- Kohler, p. 18.

- "Engineers Plan Impressive Water Approach to City." Washington Post. September 6, 1927.

- "Capitol Plaza Bill Goes to President." Washington Post. April 7, 1928.

- "Capitol Plaza Plans Made By Commission." Washington Post. April 20, 1928.

- "Plans Completed to Widen Thirteen More City Streets." Washington Post. February 3, 1929.

- "Park Heads to Discuss Widening of B Street." Washington Post. March 8, 1929.

- "B Street Roadway Lines Established By Planning Group." Washington Post. March 9, 1929.

- "L'Enfant Opposed As B Street Name." Washington Post. May 21, 1930.

- "'Constitution Avenue' Spurned for B Street." Washington Post. July 2, 1930.

- AP (8 February 1931). "'Constitution Avenue' Bill Passed as House Honors Dean". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

"B Street Name Change Favored by Committee." Washington Post. February 10, 1931. - 46 Stat. 1419

- "Two Bills for District Are Signed By Hoover." Washington Post. February 26, 1931.

- Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, 1930, p. 80-81.

- "Bids for $2,000,000 Road Jobs Opened." Washington Post. May 28, 1930.

- "41 Paving Projects Given to Congress." Washington Post. December 4, 1930.

- "City Starts Work on $10,000,000 Job." Washington Post. March 1, 1931.

- "Constitution Avenue Widening Is Ordered." Washington Post. May 14, 1931.

- "Avenue Widening Moves Landmark." Washington Post. May 19, 1931.

- "Lampposts Studied for Memorial Span." Washington Post. February 28, 1932.

- "Lee Highway Bridge Fund Cut From Bill." Washington Post. March 3, 1932.

- "Memorial Bridge Fund Stricken." Washington Post. April 8, 1932.

- "12 Paving Projects and Bridge Planned." Washington Post. December 8, 1932.

- "Gotwals Planning to Finish Several Big Highway Jobs." Washington Post. June 13, 1933.

- "Commissioners Approve Plans On Road Work." Washington Post. July 8, 1933.

- "Work for 150 Men Created By Street Job." Washington Post. July 15, 1933.

- "Lights to End Traffic Tangle." Washington Post. August 17, 1933.

- "Street Work Will Advance On Tax Funds." Washington Post. September 20, 1933.

- "City Projects to Arts Board." Washington Post. October 7, 1933.

- "District Leads States in Road Work Speed." Washington Post. October 9, 1933; "City Projects For $523,760 Given Approval." Washington Post. November 4, 1933.

- "Plan for More Traffic Lights Here Approved." Washington Post. December 2, 1933.

Bibliography

- Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission. The Arlington Memorial Bridge. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1924.

- Bednar, Michael J. L'Enfant's Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Curry, Leonard P. The Emergence of American Urbanism, 1800-1850. Vol. 1: The Corporate City. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1997.

- Dilts, James D. The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828–1853. Palo Alto, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8047-2235-8

- Gutheim, Frederick A. and Lee, Antoinette J. Worthy of the Nation: Washington, D.C., From L'Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. 2d ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Harrison, Robert. Washington During Civil War and Reconstruction: Race and Radicalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Heine, Cornelius W. "The Washington City Canal." Records of the Columbia Historical Society. 1953/1956, p. 1-27. JSTOR 40067664

- Kohler, Sue A. The Commission of Fine Arts: A Brief History, 1910-1995. Washington, D.C.: United States Commission of Fine Arts, 1996.

- Report of the Chief of Engineers. War Department Annual Reports, 1917. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918.

- Sherrill, C.O. First Deficiency Appropriation Bill, 1922. Hearings Before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations on H.R. 9237. Subcommittee on Appropriations. Committee on Appropriations. U.S. Senate. 67th Cong., 2d sess. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1921.

- Tindall, William. Standard History of the City of Washington From a Study of the Original Sources. Knoxville, Tenn.: H.W. Crew & Co., 1914.