Proterochampsa

Proterochampsa is an extinct genus of proterochampsid archosauriform from the Late Triassic (Carnian-Norian boundary) of South America. The genus is the namesake of the family Proterochampsidae, and the broader clade Proterochampsia. Like other proterochampsids, Proterochampsa are quadruped tetrapods superficially similar in appearance to modern crocodiles, although the two groups are not closely related.[1] Proterochampsids can be distinguished from other related archosauriformes by characters such as a dorsoventrally flattened, triangular skull with a long, narrow snout at the anterior end and that expands transversally at the posterior end, asymmetric feet, and a lack of postfrontal bones in the skull, with the nares located near the midline.[2] Proterochampsa is additionally defined by characters of dermal sculpturing consisting of nodular protuberances on the skull, antorbital fenestrae facing dorsally, and a restricted antorbital fossa on the maxilla.[3] The genus comprises two known species: Proterochampsa barrionuevoi and Proterochampsa nodosa. P. barrionuevoi specimens have been discovered in the Ischigualasto Formation in northwestern Argentina,[3] while P. nodosa specimens have been found in the Santa Maria supersequence in southeastern Brazil.[4] The two species are distinct in several characters, including that P. nodosa has larger, more well-developed nodular protuberances,[1] a more gradually narrowing snout, and a higher occiput than P. barrionuevoi.[2][1] Of the two, P. nodosa is thought to have less derived features than P. barrionuevoi.[5]

| Proterochampsa Temporal range: Carnian ~ | |

|---|---|

| |

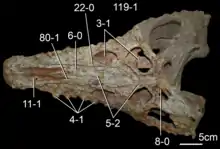

| The holotype skull of Proterochampsa nodosa (MCP 1694) in dorsal view | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Proterochampsia |

| Family: | †Proterochampsidae |

| Genus: | †Proterochampsa Reig 1959 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Discovery

Proterochampsa barrionuevoi

All known Proterochampsa barrionuevoi specimens have been discovered in the Cancha de Bochas, La Peña, Valle de la Luna, and Cerro Las Lajas members of the Ischigualasto Formation in the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin in northwestern Argentina.[3] The Ischigualasto Formation as a whole is well-known to paleontologists from its rich fossil record of flora and fauna, with the latter including fishes and a variety of tetrapod lineages. The record from Ischigualasto Provincial Park in the Argentinian province of San Juan has been particularly well-studied. Because of this abundant fossil record and the biodiversity it represents, the formation has been valuable in the study of the Late Triassic, particularly regarding the evolution of dinosaurs and other tetrapods.[3] The Ischigualasto Formation is Late Triassic in age, straddling the boundary between the Carnian and Norian stages. Using the U-Pb isotopic method, the Hoyada del Cerro Las Lajas site within the formation has been dated, with an upper boundary around 221.36 million years ago and a lower boundary around 230.32 million years ago.[3] At this site, nearly all known fossils have been discovered within the lower (and thus older) section of the Ischigualasto Formation, with most fossils estimated to age just under 228.97 million years old, placing them near the Carnian-Norian boundary. The more fossil-rich lower section of the formation can be divided into two biozones named for the rhynchosaurs most abundant within them: the lower portion is rich in Hyperodapedon specimens, and the upper portion is rich in Teyumbaita specimens. One P. barrionuevoi specimen was found at the Hoyada del Cerro Las Lajas site in the Teyumbaita biozone. This dating places P. barrionuevoi in an environment consisting of rhynchosaur-dominated faunas.[3] The biostratigraphy recorded at this site also supports the ability for researchers to correlate dating to other sites within the Ischigualasto Formation and other sites outside the formation where Proterochampsa specimens have been discovered.

Proterochampsa nodosa

Proterochampsa nodosa specimens have all been found in the Santa Maria Supersequence within the Rosário do Sul Group in the Paraná Basin in southeastern Brazil.[4] Similarly to the Ischigualasto Formation, the Santa Maria Formation is rich in Triassic tetrapod fossils, and well-known for this record. Although the Rosário do Sul Group represents a range of faunal stages during the Triassic, the portion of the Santa Maria Formation where P. nodosa has been found is specifically estimated to be near the Carnian-Norian boundary in age, supporting a similarity in age between P. barrionuevoi and P. nodosa specimens.[3][4] P. nodosa has been found in the lower portion of the Highstand systems tract of the Santa Maria 2 sequence, near the boundary between the Santa Maria and Caturrita formations within the broader Santa Maria supersequence.

History

Since their discovery starting in the early twentieth century, the taxa of the clade Proterochampsia have been assigned a number of different phylogenetic placements, including as relatives of early crocodiles, phytosaurs, or proterosuchids, eventually being recognized as non-archosaur archosauriformes.[6] The first member of the genus Proterochampsa to be discovered was Proterochampsa barrionuevoi. In 1959, Reig described a specimen from the Ischigualasto Formation, and suggested that the species could be related to early crocodiles.[7] When describing the same specimen in 1967, Sill supported this idea, and additionally denominated the family Proterochampsidae within the order Crocodilia to include the single known species. The first suggestion that proterochampsids had aquatic or semiaquatic lifestyles came from Romer in 1971, citing the dorsal position of the nares, which would make it easier for proterochampsids to breathe in aquatic environments, as evidence. Despite pointing out that the only character shared between proterochampsids and crocodilians was a secondary palate, Romer still used this character as supporting evidence for a potential aquatic or semiaquatic lifestyle for proterochampsids.[7]

A Proterochampsa nodosa specimen from the Santa Maria Formation was discovered and named by Barberena in 1982, who placed the species within Proterochampsa and Proterochampsidae.[7] In 2000, Kischlat and Schultz proposed a new genus definition for P. nodosa, instead naming the taxon Barbarenachampsa nodosa. However, this new synonym is contested because it has not been formalized, and has received inconsistent use.[4] By 2009, aquatic or semiaquatic lifestyles had been proposed for all proterochampsids by Schultz, and the group was no longer considered to be closely related to crocodiles or phytosaurs. Today, Proterochampsa and related taxa are generally considered archosauriformes, but a variety of more specific phylogenetic placements have been proposed and it remains unclear exactly where these taxa should be placed.[7]

The Proterochampsa genus was known mainly from skulls and postcrania that did not extend posteriorly past the most anterior dorsal vertebrae until the description of a new P. barrionuevoi specimen by Trotteyn in 2011. This new specimen was much more complete, and included the skull, the complete vertebral series, pelvic girdle, right hindlimb, and portions of the pectoral girdle and two other limbs. This allowed for an amended and more complete definition than the original for the species.[2]

Description

Skull

Both Proterochampsa barrionuevoi and Proterochampsa nodosa are recognizable by their distinctly triangular, dorsoventrally flattened skulls. Proterochampsa specimens have an average skull length of 50 centimeters.[8] The skull extends laterally at the posterior end to form a large temporal region, then narrows more anteriorly to form a long, narrow snout that comprises around two-thirds of the skull lengthwise.[8] The orbits, external nares, and antorbital and temporal fenestrae all face dorsally.[8][9] Proterochampsids have serrated, conical, and laterally compressed marginal teeth, resembling those of modern gharials. Proterochampsa has fewer teeth than other proterochampsids.[9] There are a number of other synapomorphies present in the skull that distinguish the genus Proterochampsa from others, including a reduced antorbital fossa, a ventral lamina on the angular, a divergent occipital margin, and the lack of a fossa around the supratemporal fenestra.[8] The description of a P. barrionuevoi braincase by Trotteyn and Haro in 2009 examined several additional neurocranial features specific to the species, including a V-shaped ridge around the basisphenoidal fossa with convex branching, and a ventrolaterally exposed semilunar depression on the parabasisphenoid.[10] Both species within the Proterochampsa genus have prominent dermal sculpturing in the form of pits, ridges and nodular protuberances on a variety of cranial bones.[8][9] This feature, which distinguishes Proterochampsa from other proterochampsids, presents distinctly in each species. In P. barrionuevoi, the nodular protuberances are smaller and more sporadically positioned, while in P. nodosa, they are more organized, larger, and more well-developed.[2][1] Other features that distinguish the two species include a higher occiput, a more gradually narrowing snout,[2] and a less pronounced anterior depression on the antorbital fenestra in P. nodosa.[7][1]

Postcrania

Historically, knowledge of Proterochampsa postcrania did not extend posteriorly past the most anterior dorsal vertebrae, until a more complete P. barrionuevoi specimen was described in 2011 by Trotteyn.[2] However, a fully complete skeleton of either species has not yet been found. Proterochampsa are known to be quadrupedal, while the posture of proterochampsians as a whole is unclear due to their intermediate tarsal type that lies between crurotarsal and mesotarsal. They are an exception to many other archosauriformes, for which tarsal type is often a clearer indicator of posture.[9] The available postcrania of P. barrionuevoi shows 24 presacral vertebrae with the neural spines located on the posterior portions, and development of the posterior portions of the neural arches.[2] In contrast to other proterochampsids, which have a single row of compact,[11] rounded osteoderms along their back, with some variation in size and positioning compared to the vertebrae,[9] the genus Proterochampsa do not have osteoderms.[2][9]

Paleobiology

The lifestyle of Proterochampsa and other proterochampsids has been contested, and a number of suggestions having been proposed. Many early descriptions of proterochampsids assumed aquatic or semiaquatic lifestyles similar to modern crocodiles, due to the superficial similarities shared between the two groups, including dorsoventrally flattened skulls and orbits and external nares that face dorsally.[9] However, some more recent studies have called into question this assumption, and have proposed terrestrial/amphibious or distinctly terrestrial lifestyles for some taxa. Several of these studies use the histology of bones or osteoderms in order to infer lifestyle. From bone histology indicating compactness comparable to modern terrestrial squamates, a terrestrial lifestyle has been suggested for the proterochampsid Chanaresuchus bonapartei, and by extension, several other related proterochampsids sharing similar morphology. Notably, Proterochampsa is distinct enough from these other taxa that it could have potentially had a semiaquatic lifestyle despite this new discovery.[12]

A number of notable proterochampsid features either tentatively suggest a terrestrial lifestyle if compared to modern reptile taxa, such as tail morphology, or are too ambiguous to definitively suggest one kind of lifestyle over another, such as a simple secondary palate, palatal teeth, an asymmetric foot, and osteoderms.[9] The gharial-like teeth in proterochampsids have been suggested to be indicative of a piscivorous diet and thus a semiaquatic lifestyle, but due to Proterochampsa having fewer teeth than other proterochampsids, the genus may potentially be excluded from this assumption.[9] The compact nature of proterochampsid osteoderms has been suggested by some to be evidence of a semiaquatic lifestyle due to a higher bone mass, despite the small size and low number of osteoderms not supporting a large increase in bone mass overall.[11] This is another debate that may not be relevant to Proterochampsa, as osteoderms are not present in either species within the genus.[9] Overall, this leaves Proterochampsa in particular with few features that can be used as definitive evidence of lifestyle, and some paleontologists have called specifically for deeper analysis of lifestyle for the genus.[12]

Studies of bone histology in proterochampsids have used the discovery of highly vascular and fibrolamellar bone tissue as evidence for rapid growth rates.[9][12] Notably, there is variation within some species,[12] and inconsistencies found in some studies suggest that proterochampsids may have had developmental plasticity, meaning their growth rates were variable and could respond to environmental changes.[9] Like other proterochampsids, the two Proterochampsa species are thought to be predatory.[1]

Paleoecology

P. nodosa lived in an environment with increasing humidity, when a brief system of anastomosing rivers and lakes was gradually giving way to an enduring system of braided rivers.[4] Using Hyperodapedon-defined biozones similarly to in the Ischigualasto Formation, paleontologists have suggested that P. nodosa would have also lived in a rhynchosaur-dominated environment, with rhynchosaur specimens accounting for 90% of Carnian specimens in the Santa Maria Formation.[4] Other proterochampsian species have been found within the Rosário do Sul Group, including Rhadinosuchus gracilis, Cerritosaurus binsfeldi, and Chanaresuchus bonapartei.[4]

References

- De Simão-Oliviera, Daniel; Pinheiro, Felipe Lima; De Andrade, Marco Brandalise; Pretto, Flávio Augusto (2022). "Redescription, taxonomic revaluation and phylogenetic affinities of Proterochampsa nodosa (Archosauriformes: Proterochampsidae) from the early Late Triassic of the Candelaria Sequence (Santa Maria Supersequence)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 196 (4): 1310–1332. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlac048.

- Trotteyn, M. Jimena (2011). "Material Postcraneano de Proterochampsa barrionuevoi Reig 1959 (Diapsida: Archosauriformes) del Triásico Superior del Centro-oeste de Argentina". Ameghiniana. 48 (4): 424–446. doi:10.5710/AMGH.v48i4(351). hdl:11336/197236. S2CID 130001247.

- Desojo, Julia B.; Fiorelli, Lucas E.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Martinelli, Agustín G.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Da Rosa, Átila A. S.; von Baczko, M. Belén; Trotteyn, M. Jimena; Montefeltro, Felipe C.; Ezpeleta, Miguel; Langer, Max C. (29 July 2020). "The Late Triassic Ischigualasto Formation at Cerro Las Lajas (La Rioja, Argentina): fossil tetrapods, high-resolution chronostratigraphy, and faunal correlations". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 12782. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-67854-1. PMC 7391656. PMID 32728077.

- Langer, Max C.; Ribiero, Ana M.; Schultz, Cesar L.; Ferigolo, Jorge (2007). Lucas, S. G.; Spielmann, J. A. (eds.). "The Continental Tetrapod-Bearing Triassic of South Brazil". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 41: 201–218.

- Kischlat, E.; Schultz, C. L. (1999). "Phylogenetic Analysis of Proterochampsia (Thecodontia: Archosauriformes)". Ameghiniana. 36 (4): 13R.

- Nesbitt, Sterling J. (29 April 2011). "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origins of Major Clades". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292. doi:10.1206/352.1. S2CID 83493714.

- Trotteyn, María Jimena. Revisión Osteologica, Análisis Filogenético y Paleoecología de Proterochampsidae (Reptilia - Arcosauriformes) (PhD). Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

- Dilkes, David; Arcucci, Andrea (19 June 2012). "Proterochampsa barrionuevoi (Archosauriformes: Proterochampsia) from the Late Triassic (Carnian) of Argentina and a phylogenetic analysis of Proterochampsia". Palaeontology. 55 (4): 853–885. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01170.x. S2CID 129670473 – via Wiley Online Library.

- Arcucci, Andrea; Previtera, Elena; Mancuso, Adriana C. (2019). "Ecomorphology and bone microstructure of Proterochampsia from the Chañares Formation". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 64 (1): 157–170. doi:10.4202/app.00536.2018. S2CID 134821780.

- Trotteyn, María Jimena; Haro, José Augusto (March 2011). "The braincase of a specimen of Proterochampsa Reig (Archosauriformes: Proterochampsidae) from the Late Triassic of Argentina". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 85: 1–17. doi:10.1007/s12542-010-0068-7. S2CID 129156275 – via Springer.

- Cerda, Ignacio A.; Desojo, Julia B.; Trotteyn, María; Scheyer, Torsten (2015). "Osteoderm Histology of Proterochampsia and Doswelliidae (Reptilia: Archosauriformes) and Their Evolutionary and Paleobiological Implications". Journal of Morphology. 276 (4): 385–402. doi:10.1002/jmor.20348. hdl:11336/4978. PMID 25640219. S2CID 44377068.

- Ponce, Denis A.; Trotteyn, M. Jimena; Cerda, Ignacio A.; Fiorelli, Lucas E.; Desojo, Julia B. (2021). "Osteohistology and paleobiological inferences of proterochampsids (Eucrocopoda: Proterochampsia) from the Chañares Formation (late Ladinian–early Carnian), La Rioja, Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (2). doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1926273. S2CID 237518073.

Further reading

- F. Abdala, M. C. Barberena, and J. Dornelles. 2002. A new species of the traversodontid cynodont Exaeretodon from the Santa Maria Formation (Middle/Late Triassic) of southern Brazil. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22(2):313-325

- * O. A. Reig. 1963. La presencia de dinosaurios saurisquios en los "Estratos de Ischigualasto" (Mesotriasico Superior) de las provincias de San Juan y La Rioja (República Argentina) [The presence of saurischian dinosaurs in the "Ischigualasto beds" (upper Middle Triassic) of San Juan and La Rioja Provinces (Argentine Republic)]. Ameghiniana 3(1):3-20

- The Beginning of the Age of Dinosaurs: Faunal Change across the Triassic-Jurassic Boundary by Kevin Padian