Colobops

Colobops is a genus of reptile from the Late Triassic of Connecticut.[1][2] Only known from a tiny skull (estimated total length of 2.8 centimeters or 1.1 inches long),[3] this reptile has been interpreted to possess skull attachments for very strong jaw muscles. This may have given it a very strong bite, despite its small size.[1] However, under some interpretations of the CT scan data, Colobops's bite force may not have been unusual compared to other reptiles.[2] The generic name, Colobops, is a combination of κολοβός (kolobós), meaning shortened, and ὤψ (ṓps), meaning face. This translation, "shortened face", refers to its short and triangular skull. Colobops is known from a single species, Colobops noviportensis. The specific name, noviportensis, is a latinization of New Haven, the name of both the geological setting of its discovery (the New Haven Arkose) as well as a nearby large city. The phylogenetic relations of Colobops are controversial. Its skull shares many features with those of the group Rhynchosauria, herbivorous archosauromorphs distantly related to crocodilians and dinosaurs. However, many of these features also resemble the skulls of the group Rhynchocephalia, an ancient order of reptiles including the modern tuatara, Sphenodon.[3] Although rhynchosaurs and rhynchocephalians are not closely related and have many differences in the skeleton as a whole, their skulls are remarkably similar. As Colobops is only known from a skull, it is not certain which one of these groups it belonged to. Pritchard et al. (2018) interpreted it as a basal rhynchosaur,[1] while Scheyer et al. (2020) reinterpreted it as a rhynchocephalian.[2]

| Colobops Temporal range: Middle Norian | |

|---|---|

| |

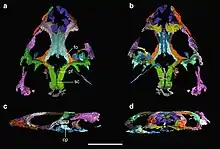

| A 3D reconstruction of the skull of Colobops, based on scan data obtained by Pritchard et al. (2018) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | Lepidosauria |

| Order: | Rhynchocephalia |

| Suborder: | Sphenodontia |

| Genus: | †Colobops Pritchard et al., 2018 |

| Species: | †C. noviportensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Colobops noviportensis Pritchard et al., 2018 | |

History

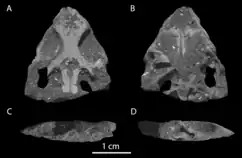

The holotype skull of Colobops, YPM VPPU 18835, is mostly complete, although flattened and missing tooth-bearing portions of the cranial bones. The specimen was discovered in 1965 during highway construction in central Connecticut between the towns of Middletown and Meriden.[3] This locale is part of the New Haven Arkose, a subdivision of the Newark supergroup. The Newark supergroup is a collection of Late Triassic formations along the eastern coast of North America, and the New Haven Arkose has specifically been Uranium-Lead dated to the mid Norian age, about 214.0 to 209.8 million years ago.[4]

The skull was not described in an academic context until 1993, although photographs of the specimen had been featured in "A pictorial guide to fossils", a natural history book published by G.R. Case in 1982. A formal study of the specimen by Hans-Dieter Sues and Donald Baird in 1993 offered a discussion of its classification, but did not provide a scientific name for the reptile in question. This study considered the skull to lack a lacrimal bone, and noted that it originally possessed supposed fang-like premaxillary teeth at the tip of the snout which were accidentally destroyed during preparation. These features led Sues & Baird to assign the skull to Sphenodontia, a group containing most rhynchocephalians.[3]

The specimen finally received a formal name in early 2018, when a group led by Adam Pritchard provided new preparation and discussion of the skull, as well as giving it the name Colobops noviportensis. This study also included CT-scans of the specimen, proportional and numerical analyses of the enlarged temporal region, and a phylogenetic analysis in order to determine its relations. The most parsimonious results of the phylogenetic analysis indicated that the reptile was a basal rhynchosaur, although the analysis also showed that a position within Rhynchocephalia was only slightly less likely to be true.[1] A 2020 reinterpretation by Torsten Scheyer et al. argued that the skull was crushed and several bones were displaced, and that it more closely resembled a rhynchocephalian once these issues were rectified.[2]

Description

The snout of Colobops is very short, with the portion of the skull in front of the eyes occupying only a quarter of the total length of the skull. This portion of the snout is also reinforced by overlapping bones. For example, the nasal bones (on the upper side of the snout) droop down to internally brace the maxillae (bones of the side of the snout). This feature is also known in rhynchosaurs and rhynchocephalians. The maxillae are also protected by the large prefrontals (bones in front of the eyes), similar to the condition in turtles. The prefrontals are also contacted by the wide palatine bones of the roof of the mouth, similar to lepidosaurs (squamates and rhynchocephalians), as well as turtles. All of these features exist to strengthen the front part of the skull, which explains how they convergently evolved in multiple different types of reptiles.[1]

Colobops also possesses large orbits (eye holes), although this may be a juvenile feature. The upper edge of each orbit is formed by the upper rear branch of a prefrontal and the upper forward branch of a postfrontal (bone behind the eye). This means that the frontals (bones of the skull roof between the eyes) are separated from the orbit, a feature which is known to a lesser degree in Sphenodon and Clevosaurus, but not rhynchosaurs.[2] Another diagnostic feature of Colobops is the fact that the skull roof possesses a very large, diamond-shaped gap between its bones, referred to as a fontanelle. Fontanelles typically can be used to characterize infant animals with skull roofs that are not completely fused. However, under the interpretation that the skull has overlapping bones and large sites for muscle attachment, the skull could be interpreted as belonging to a much older animal. A few species of modern iguanians retain their fontanelles in adulthood, and it is conceivable that Colobops was similar.[1] The presence of a fontanelle would be less unprecedented if the skull belonged to a juvenile.[2]

The rear part of the skull roof, formally known as the supratemporal area, has a pair of large holes known as supratemporal fenestrae. These holes were initially interpreted as quite broad in Colobops, similar to derived rhynchosaurs.[1] However, later analyses argued that this apparent expansion was a misinterpretation due to the squamosal being displaced and the postorbital being incomplete.[2] Only a small area of bone is present between the supratemporal fenestrae. This area of bone, formed by the fusion of the two parietal bones, has a thin sagittal crest running down its midline. This crest would have attached to powerful muscles for closing the jaw, such as the m. adductor mandibulae profundus and the m. pseudotemporalis superficialis. Colobops would have been the smallest known reptiles to possess such a powerful and expanded supratemporal area,[1] although uncertainty in the shape of the skull may oppose this interpretation.[2]

Although the braincase is only partially known, certain features can be recognized. The supraoccipital (upper part of the braincase) has small prongs which brace the parietals from behind. Unlike some lepidosaurs, Colobops possesses a fully ossified thin and tall plate-like bone known as a parasphenoid rostrum, which extends forward along the midline of the rear part of the roof of the mouth. The epipterygoids (column-like bones between the pterygoids and braincase) are large and tall, and would have been the lower attachment point for the m. pseudotemporalis superficialis. The only preserved portion of the mandible (lower jaw) was a large and pointed coronoid process near the rear part of the skull. It would have been the lower attachment point for the m. adductor mandibulae profundus.[1]

Classification

In order to determine which reptile group Colobops truly belonged to, its describers (Pritchard et al.) included it within a phylogenetic analysis. Their analysis was a modified version of one originally designed by Pritchard & Nesbitt (2017) to test the affinities of the beaked drepanosaur Avicranium. With Colobops incorporated into the analysis and several character scores updated, the most parsimonious tree found that Colobops was an archosauromorph as the earliest diverging member of Rhynchosauria. This position was supported by three features of the snout and one feature of the supratemporal area. Like rhynchosaurs, Colobops had a shortened snout with a maxilla that overlaps the nasal. In addition, the supratemporal fenestrae of Colobops and rhynchosaurs are positioned high on the skull, about the same level as the upper edge of the orbit. Other archosauromorphs, such as Prolacerta, had supratemporal fenestrae in a slightly lower position, with the bones forming the outer edge of the holes being positioned about midway up the orbit.[1]

However, this classification was only slightly better supported than certain alternative interpretations. A phylogenetic analysis constructs thousands of family trees, each of which include hundreds of "steps" in evolution where analyzed traits are evolved, lost, or reacquired. The family tree with the fewest "steps", known as the most parsimonious tree (MPT), is generally considered to be the most accurate under the principle of Occam's razor. In the case of this analysis, the MPT considered Colobops to be a basal rhynchosaur. However, some family trees look completely different from the MPT despite only a being few evolutionary steps more complex. If new data is incorporated into the analysis, one of these alternative trees may become a new MPT, rewriting our knowledge of reptile classification in the process. The MPT given by Pritchard et al. (2018) is given below:[1]

| Sauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prior to receiving a formal name and description, the holotype of Colobops noviportensis was actually believed to be a rhynchocephalian upon its discovery and preliminary description by Sues & Baird (1993).[3] This alternative position for Colobops was tested by Pritchard et al. in their phylogenetic analysis. The analysis found that the simplest family trees including Colobops within Rhynchocephalia were only 2 steps more complex than the MPT of the analysis, which considered it a rhynchosaur. In these trees, the closest relatives of Colobops were clevosaurs such as Clevosaurus. Two of the features which supported the assignment of Colobops as a basal rhynchosaur also happen to support its assignment as a rhynchocephalian, an example of convergent evolution between the two groups. These features include a maxilla which overlaps the nasal, and supratemporal fenestrae positioned high on the skull. In addition, the unfused frontal bones of Colobops also support a place among rhynchocephalians. The strict consensus (average result) of the simplest family trees which include Colobops within Rhynchocephalia is given below. In this strict consensus tree, the structure of Archosauromorpha is reduced to a polytomy, depicting a compromise between many family trees with competing structures but equal complexity.[1]

| Sauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Many aspects of the anatomy of Colobops makes it difficult to evaluate its classification. One possibility is that the specimen is an infant, as supported by its large eyes, small size, and massive fontanelle in the skull roof. Juvenile specimens are notorious for jeopardizing the results of phylogenetic analyses, as diagnostic traits within adult species would not have developed yet.[1] However, the supposed massive jaw musculature of Colobops would be highly unusual for a young reptile, even compared to other rhynchosaurs (which are known to develop diagnostic traits at a young age).[5]

The redescription by Scheyer et al. (2020) expanded the data matrix with additional lepidosauromorph characteristics and taxa. In this expansion, Colobops is positioned as a rhynchocephalian next to Sphenodon (the tuatara), with a minimum of 17 steps required to place it back as a basal rhynchosaur.[2]

Paleobiology

The interpretation of Pritchard et al. (2018) supports the idea that Colobops possessed large jaw muscles. Most modern reptiles enlarge their jaw musculature by two methods, either developing large muscle receptor areas on the parietals bones in the middle of the skull, or by the supratemporal fenestrae being widened. Colobops, however, may have developed both of these methods at the same time, giving it a bite force unprecedented for its body size. This would have been further assisted by the tall coronoid process of the lower jaw. The heavily reinforced snout likely evolved in conjunction with the development of strong jaw muscles. Based on comparisons with both rhynchosaurs and rhynchocephalians, Colobops can safely be presumed to have fed using precise and strong bites, although it cannot be determined whether this was for carnivory (as in the tuatara) or herbivory (as in rhynchosaurs), as no teeth have been preserved. The bones at the edge of the jaws were broad, a condition which is shared by living lizards such as Chamaeleolis chamaeleonides (the Cuban false chameleon) and Dracaena guianensis (the Northern caiman lizard). These lizards specialize in hard-shelled prey such as crustaceans and snails.[1]

However, Scheyer et al. (2020) reinterpreted the supratemporal fenestrae as much narrower in life, with crushing and bone displacement artificially expanding the fossil. Plotting Colobops with other reptiles according to these new proportional estimates shows that Colobops did not have unusually large jaw muscles for its size.[2]

References

- Pritchard, Adam C.; Gauthier, Jacques A.; Hanson, Michael; Bever, Gabriel S.; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S. (2018-03-23). "A tiny Triassic saurian from Connecticut and the early evolution of the diapsid feeding apparatus". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 1213. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.1213P. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03508-1. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5865133. PMID 29572441.

- Scheyer, Torsten M.; Spiekman, Stephan N. F.; Sues, Hans-Dieter; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Butler, Richard J.; Jones, Marc E. H. (25 March 2020). "Colobops: a juvenile rhynchocephalian reptile (Lepidosauromorpha), not a diminutive archosauromorph with an unusually strong bite". Royal Society Open Science. 7 (3): 192179. Bibcode:2020RSOS....792179S. doi:10.1098/rsos.192179. PMC 7137947. PMID 32269817.

- Sues, Hans-Dieter; Baird, Donald (1993). "A Skull of a Sphenodontian Lepidosaur from the New Haven Arkose (Upper Triassic: Norian) of Connecticut". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 13 (3): 370–372. doi:10.1080/02724634.1993.10011517. JSTOR 4523519.

- Wang, Z.S.; Rasbury, E.T.; Hanson, G.N.; Meyers, W.J. (1998-08-01). "Using the U-Pb system of calcretes to date the time of sedimentation of clastic sedimentary rocks". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 62 (16): 2823–2835. Bibcode:1998GeCoA..62.2823W. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00201-4. ISSN 0016-7037.

- Benton, Michael J.; Kirkpatrick, Ruth (July 1989). "Heterochrony in a fossil reptile: juveniles of the rhynchosaur Scaphonyx fischeri from the Late Triassic of Brazil" (PDF). Palaeontology. 32 (2): 335–353.