Battle of Berezina

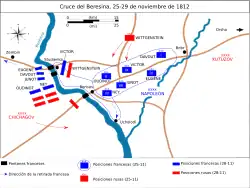

The Battle of (the) Berezina (or Beresina) took place from 26 to 29 November 1812, between Napoleon's Grande Armée and the Imperial Russian Army under Field Marshal Wittgenstein and Admiral Chichagov. Napoleon was retreating back toward Poland in chaos after the aborted occupation of Moscow and trying to cross the Berezina River at Borisov. The outcome of the battle was inconclusive as, despite heavy losses, Napoleon managed to cross the river and continue his retreat with the surviving remnants of his army.[6]

| Battle of the Berezina | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French invasion of Russia | |||||||

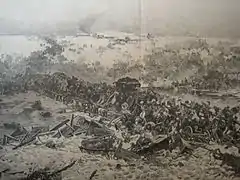

Napoleon's crossing of the Berezina, a 1866 painting by January Suchodolski, oil on canvas, National Museum, Poznań | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

~36,000 effectives[1] At least 40,000 stragglers[2] 250–300 guns[3] | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

20,000 to 30,000 combatants[5] 30,000 noncombatants[5] |

10,000 killed Many more wounded[5] | ||||||

Location within Europe | |||||||

Background

Napoleon had fought his way out of Russia in the battles of Maloyaroslavets, Vyazma and Krasnoi. His plan was to cross the Berezina River at Borisov (in Belarusian Governorate General) in order to join up with his Austrian ally, Field Marshall Schwarzenberg at Minsk.[7] As the central core of Napoleon's Grande Armée marched toward Borisov, however, Russian troops supported by Cossacks moved to block his battered force, reduced to 49,000 men under arms and 40,000 stragglers.[8]

On 21 November, the Russians attacked and captured the French garrison at Borisov including the bridge over the Berezina. A French advance force attempted to regain Borisov on 23 November, but the Russians destroyed the bridge and remained in control of the west bank.[9][10] To the north, Russian field marshal Wittgenstein and an army of 30,000 tracked Napoleon as he moved west. From Minsk in the west, Russian admiral Chichagov (with Chaplits in the vanguard) and an army of 35,000 advanced toward Borisov.[11] And pursuing Napoleon's army from the east was Russian General Miloradovich with a force of an additional 32,000 soldiers.[12]

On 23 November 1812, the Sacred Squadron (French: L'escadron sacré) was formed as an ad hoc cavalry unit which consisted – out of military necessity – entirely of officers to serve as Napoleon's bodyguard.

Russian field marshal Kutuzov with another 39,000 men was in the vicinity, 64 kilometres to the east, but was not involved in the fighting. General Sir Robert Wilson, a British liaison officer traveling with Kutuzov, advocated for a direct confrontation with Napoleon and protested against the Russian strategy allowing Napoleon to withdraw with only peripheral attacks. Kutuzov replied that he was not at all sure that the total destruction of the Emperor Napoleon and his army would be such a benefit to Russia, as Britain would then dominate Europe, and that would be intolerable.[13]

The crossing and battles

.jpg.webp)

As Napoleon's army reached Bobr, 50 kilometres from Borisov, he was informed that the bridge over the Berezina at Borisov had been destroyed. Napoleon also learned that a French cavalry brigade had discovered a place where the river might be crossed eight miles north of Borisov at the hamlet of Studienka. Although this was a place where an ice crossing could normally be made in November, a temporary thaw of the ice and the muddy banks made it necessary that bridges be constructed.[14][15]

Plans were made to build pontoon bridges. The commander of the pontoon bridge builders, General Jean Baptiste Eblé, had disobeyed Napoleon's previous orders given during the withdrawal to destroy the equipment, forges, and tools necessary for building bridges. To draw the Russians' attention away from the vicinity of the crossing, numerous diversions were undertaken. On 25 November, bridge construction started in Studienka even though numerous campfires belonging to the forces of Admiral Chichagov were observed across the river at Brili.[16]

The movements of French General Nicolas Oudinot's corps and numerous rumours led the Russians to believe that Napoleon would either attack at Borisov and attempt to repair the bridge or he would lead his troops south of Borisov and cross the Berezina downstream. As a result, Chichagov made the decision to move the main body of his force south of Borisov to Szabaszeviki so that he could watch and patrol a 90‑kilometre stretch of the Berezina River. Russian General Tshaplitz and his force of approximately 3,000 men camped at Brili were ordered to move 15 kilometres south to support the Russian forces at Borisov.[17]

As a result, on the morning of 26 November, the French discovered that the Russians had abandoned their camp on the west bank. Forty French cavalry troopers made their way across the river and protected the crossing of 400 men in boats. This small force then secured the west bank so that the bridges could be completed. Meanwhile, neither of the Russian forces pursuing Napoleon from the rear were very aggressive and both remained substantial distances north and west of the Berezina River while the French bridged the river.[18][19] This river was 20-30 metres wide and filled with drifting ice, but its banks are swampy, making the crossing extremely difficult.[20][21]

By 1 p.m. the smaller of the two bridges was complete and Oudinot began to lead his infantry of 7,000 men across the river and establish a defensive position to protect against the Russian forces to the south. Later that afternoon, the larger of the two bridges (for the artillery) was completed, but collapsed twice. Napoleon began to move his force across the Berezina in earnest.[22]

Overnight on 26-27 November, Russian General Chaplitz became aware of the French crossing, consolidated his forces, and attempted to return to Brili to intercept the French. Tshaplitz's forces, however, were stopped well to the south of Brili by Oudinot's battalions. Also on the 27th, Chichagov began to move the main portion of his army back to Borisov when it became apparent that there was no French activity downstream. Chichagov, however, chose not to immediately move north to Brili inasmuch as his men were still in transit and not fully assembled.[23]

By midday of the 27th, Napoleon and his Imperial Guard were across. One of the spans broke in the late afternoon, but the engineers had it repaired by early evening.[24] The corps of Marshal Davout and Prince Eugene were able to cross before the day ended. The last unit on the eastern bank, Marshal Victor's IX Corps was given the order to defend against the approach of Wittgenstein who had then reached Borisov. As a part of that operation, French General Louis Partouneaux's 12th Division of the IX Corps suffered a great defeat, surrendering over 8,000 men when they were overwhelmed by Wittgenstein at Staroi-Borisov.[25][26]

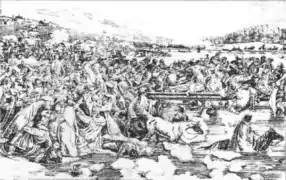

On 28 November, the Russians coordinated their efforts and attacked Napoleon's Grande Armée on both sides of the river. On the west bank, Tshaplitz reinforced with additional infantry attacked the French forward positions and began to push Oudinot back to Brili. French General Ney took command when Oudinot was wounded and the Russian advance was stopped. Twenty-five thousand men engaged in a firefight that lasted into the night. Finally, French General Doumerc led a cavalry charge of the Cuirassiers,forcing the Russians back and ending the battle for the day. On the east bank of the river, Wittgenstein attacked Victor's IX Corps at 5 a.m. The French were pushed back in fighting that went on for eight hours. At 1 p.m., the Russians attained a position that enabled them to flank the French and rain down cannon fire on the bridges. The artillery bombardment fell largely upon the stragglers causing a human stampede as individuals rushed for the bridges or jumped into the cold river in an attempt to swim to the other side. The fighting and bombardment lasted for approximately four hours at which time the bridge engineers began working to clear a path for Victor's IX Corps to cross the river. [27]

At about 10 p.m. that evening, Victor's IX Corps made their crossing and three hours later the bridges were free of Napoleon's armed troops. The bridges were then available for the stragglers; however, despite encouragement, most of those who had fought so hard to get across the river during the bombardment chose to light their campfires and spend the night on the east bank. The next morning, the commander of the engineers, General Eblé had Napoleon's order to burn the bridges at 7 a.m. Eblé delayed the execution of that order until 8:30 a.m., at which time, tens of thousands of stragglers and their civilian companions were left behind.[28]

...The unfortunate men who had not taken advantage of the night to get away had at the first appearance of dawn rushed on to the bridge, but now it was too late. Preparations were already made to burn it down. Numbers jumped into the water, hoping to swim through the floating bits of ice, but not one reached the shore. I saw them all there in water up to their shoulders, and, overcome by the terrible cold, they all miserably perished. On the bridge was a canteen man carrying a child on his head. His wife was in front of him, crying bitterly. I could not stay any longer, it was more than I could bear. Just as I turned away, a cart containing a wounded officer fell from the bridge, with the horse also. They next set fire to the bridge, and I have been told that scenes impossible to describe for horror then took place...[29]

Cossacks and Wittgenstein's troops closed in upon Studienka and took the stragglers on the east bank as prisoners. With the pontoon bridges gone, Wittgenstein had no means to cross the river and pursue Napoleon. On the west bank, Napoleon and his Grande Armée were on their way to Vilna. Chichagov sent Chaplits in pursuit of Napoleon but the French had destroyed three successive bridges across the Gaina swamp between Brili and the Zembin Road leading to Vilna. The swamp could not be crossed without the bridges. Napoleon had escaped. The battle at the Berezina River was over.[30][31]

Casualties

Author David G. Chandler wrote in "The Campaigns of Napoleon"[5]

_(2).jpg.webp)

"... the cost in terms of human lives will never be known with any accuracy. Probably between 20-30,000 French combatants became casualties during the three days of the operation; worst hit in this respect were the IInd and IXth Corps, which lost more than half of their effective strength in their important roles of protecting the bridgehead area. To the number of the slain in action must be added probably as many as 30,000 noncombatants; not all these died during the crossing operation, but the large number that fell into Russian hands succumbed almost to a man of exposure and starvation during the following days. Huge quantities of booty fell into the hands of the Cossacks, but it is noteworthy that the French only abandoned 25 guns to the enemy. For their part, the Russians lost at least 10,000 killed over the same period and many more wounded."

Aftermath

The immediate result of the battle of Berezina had been simple: the French retreat went on, the Russian Army followed. Although it had been a Russian tactical victory by definition as the losses of the "defeated" outweighed those of the "victor", the victorious Russian force failed to meet its original objectives. Indeed, despite enormous losses, Napoleon was in a position to claim a strategic victory, having snatched what was left of his army from a seemingly unavoidable catastrophe. There would be no large military confrontation for the rest of the retreat, although the incessant harassment of Russian Cossacks and the weather continued to take a toll on the surviving members of the French army.[32]

The losses had been extraordinary. It is estimated that 20–30,000 French combatants became casualties. "To the number of the slain in action must be added probably as many as 30,000 non-combatants."[5] The Guard, which had not come into action at all, lost about 1,500 men out of 3,500. Much, however, had been saved. Napoleon, his generals, 200 guns, the war chest, much of the baggage, and thousands of officers and veteran soldiers had escaped. Overall, approximately 40,000 members of Napoleon's army were saved. Without this core of experienced men, Napoleon could not have rebuilt his armies for the battles of the War of the Sixth Coalition.[33]

According to author Andrew Zamoyski:

The next two days were, according to some, among the worst of the entire retreat[...]no fallen horse or cattle remained uneaten, no dog, no cat, no carrion, nor indeed, the corpses of those who died of cold and hunger.[34]

Napoleon left his army on 5 December at Vilna. The temperatures dropped to -33.75 °C on 8 December and the number of combatants was down to 4,300. On 14 December the rest of the French main army crossed the Niemen. 36,000 French prisoners of the Grande Armée were taken by the Cossacks between 1–14 December. The only troops that had remained were the flanking forces (43,000 under Schwarzenberg, 23,000 under Macdonald), about 1,000 men of the Guard and about 40,000 stragglers. No more than 110,000 were all that was left from 612,000 (including reinforcements) that had entered Russia. The Russian losses may be about 250,000 men.[35] Louise Fusil, a French actress, who was living in Russia for six years, returned with the army and offers details in her memoires.

Gallery

The drama of the battle's story inspired many works of art centred on the crossing:

Crossing of the Berezina, Felician Myrbach

Crossing of the Berezina, Felician Myrbach Crossing the Berezina River on 29 November 1812, Peter von Hess

Crossing the Berezina River on 29 November 1812, Peter von Hess.jpg.webp) La traversée de la Bérézina en 1812, Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht

La traversée de la Bérézina en 1812, Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht Crossing at Berenzina, Julian Fałat

Crossing at Berenzina, Julian Fałat Übergang über die Berezina, unknown

Übergang über die Berezina, unknown.jpg.webp) Le passage de la Bérézina, Joseph Raymond Fournier-Sarlovèze

Le passage de la Bérézina, Joseph Raymond Fournier-Sarlovèze.jpg.webp) Biarezina. Бярэзіна (Victor Adam)

Biarezina. Бярэзіна (Victor Adam) Dutch engineers at the Berezina

Dutch engineers at the Berezina

Citations

- Chandler 1966, p. 840.

- Chandler 1966, p. 842.

- Chandler 1966, p. 841.

- Riehn 1990, p. 377.

- Chandler 1966, p. 846.

- Wilson 1860, p. 177.

- Riehn 1990, p. 371.

- Chandler 1966, pp. 841–842.

- Smith 1998, p. 405.

- Riehn 1990, p. 376.

- Riehn 1990, p. 368.

- Riehn 1990, p. 358.

- Wilson 1860, p. 234.

- Riehn 1990, pp. 376–378.

- Chandler 1966, pp. 833–835.

- Riehn 1990, pp. 373 and 379.

- Riehn 1990, pp. 378–379.

- Riehn 1990, pp. 373, 377-378 and 380-381.

- Chandler 1966, pp. 836–837.

- ""Höchstens so breit wie die Rue royale in Paris"".

- 29th Bulletin de la Grande armée, p. 160

- Riehn 1990, pp. 381–382.

- Riehn 1990, pp. 382–383.

- Riehn 1990, p. 382.

- Riehn 1990, p. 383.

- Smith 1998, pp. 406–407.

- Riehn 1990, pp. 384–386.

- Riehn 1990, pp. 385–386.

- Bourgogne 1899, p. 205.

- Riehn 1990, p. 381.

- Wilson 1860, pp. 334–337.

- Chandler 1966, pp. 845–847.

- Riehn 1990, p. 387.

- Zamoyski 1980, p. 482-483.

- Riehn 1990, p. 390.

References

- Balzac, Honore de (1887). The Country Doctor. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Bourgogne, Adrien Jean Baptiste François (1899). Memoirs of Sergeant Bourgogne, 1812–1813. New York, Doubleday & McClure company. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- "C'est la Bérézina: Signification et origine de l'expression". L'Internaute. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- Chambray, George de (1823). Histoire de l'expédition de Russie. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0025236608. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Riehn, Richard K. (1990). 1812 : Napoleon's Russian campaign. ISBN 978-0070527317. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1853672769.

- Wilson, Robert Thomas (1860). Narrative of events during the Invasion of Russia by Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Retreat of the French Army, 1812. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Zamoyski, Adam (1980). Moscow 1812: Napoleon's Fatal March. ISBN 978-0061075582. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

General references

- Cathcart, Sir George (1850). Commentaries on the War in Russia and Germany in 1812 and 1813. London: John Murray.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2010). Napoleon's Great Escape: The Battle of the Berezina. London: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-920-8.

- Morelock, Jerry, Napoleon's Russian nightmare. Misjudgments, Russian strategy and "General Winter" changed the course of history, 2011

- Pigeard, Alain – "Dictionnaire des batailles de Napoléon", Tallandier, Bibliothèque Napoléonienne, 2004, ISBN 2-84734-073-4

- Pigeard, Alain – "La Bérézina", Napoléon Ier Editions 2009

- Tulard, Jean – "Dictionnaire Napoléon"; Librairie Artème Fayard, 1999, ISBN 2-213-60485-1

- Weider, Ben and Franceschi, Michel, The Wars Against Napoleon: Debunking the Myth of the Napoleonic Wars, 2007

External links

The dictionary definition of bérézina at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of bérézina at Wiktionary Media related to Battle of Berezina at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Berezina at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Krasnoi |

Napoleonic Wars Battle of Berezina |

Succeeded by Battle of Castalla |