Battle of Guttstadt-Deppen

In the Battle of Guttstadt-Deppen on 5 and 6 June 1807, troops of the Russian Empire led by General Levin August, Count von Bennigsen attacked the First French Empire corps of Marshal Michel Ney. The Russians pressed back their opponents in an action that saw Ney fight a brilliant rearguard action with his heavily outnumbered forces. During the 6th, Ney successfully disengaged his troops and pulled back to the west side of the Pasłęka (Passarge) River. The action occurred during the War of the Fourth Coalition, part of the Napoleonic Wars. Dobre Miasto (Guttstadt) is on Route 51 about 20 kilometers (12 mi) southwest of Lidzbark Warmiński (Heilsberg) and 24 kilometers (15 mi) north of Olsztyn (Allenstein). The fighting occurred along Route 580 which runs southwest from Guttstadt to Kalisty (Deppen) on the Pasłęka.

| Battle of Guttstadt-Deppen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Fourth Coalition | |||||||

.jpg.webp) The Stork Tower (Baszta Bociania) in Dobre Miasto | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Guttstadt: 17,000 Lomitten: 6,000, 16 guns Spanden: unknown |

Guttstadt: 63,000 Lomitten: 12,000, 76 guns Spanden: 6,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Guttstadt: 2,042 Lomitten: 1,185 Spanden: unknown |

Guttstadt: 2,000–2,500 Lomitten: 2,800 Spanden: 500–800 | ||||||

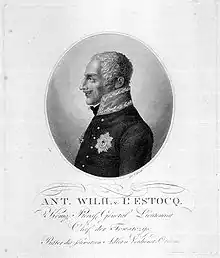

At the beginning of June, Bennigsen launched an offensive against the forces of Emperor Napoleon I in East Prussia. The Russian commander planned to trap Ney's corps between several converging columns. To occupy the French troops on Ney's left, Bennigsen sent General-Leutnant Anton Wilhelm von L'Estocq's Prussians to attack Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte's troops at Spędy (Spanden) and ordered Lieutenant General Dmitry Dokhturov's Russians to assault Marshal Nicolas Soult's men at Stolno (Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship) (Lomitten). Although all three French marshals saw sharp fighting, the Russian plan failed to put significant numbers of French troops out of action. Afraid of being cut off in his turn, Bennigsen ordered a retreat on the night of the 7th as Napoleon instructed his forces to counterattack the Russians. The decisive Battle of Friedland was fought a week later on 14 June.

Background

After the bloody Battle of Eylau on 7 and 8 February 1807, Napoleon's forces lingered in the vicinity so that the emperor could claim a victory.[3] However, his soldiers clamored for an end to the fighting. Instead of the usual shouts of Vive l'Empereur (long live the emperor), cries of Vive la paix (long live peace) were heard in the bivouacs when the emperor passed by.[4] On 17 February the French began their withdrawal westward into winter quarters.[5] By the 23rd the French reached their cantonments, with Maréchal Bernadotte's I on the left, Maréchal Soult's IV Corps in the center, and Maréchal Davout's III Corps on the right. Maréchal Ney's VI Corps occupied an advanced position at Guttstadt, while the Imperial Guard and the Reserve Cavalry occupied the rear area around Ostróda (Osterode). Napoleon stationed Maréchal Lannes V Corps in a position to cover Warsaw.[6] Maréchal Augereau's decimated VII Corps was broken up and its survivors were allotted to the other corps.[7]

L'Estocq's attempt to pursue the French came to grief at Braniewo (Braunsberg) on 26 February, when Bernadotte's corps drubbed his advance guard. In this action, the Russian-Prussian force lost 100 killed and wounded, with 700 soldiers and six guns captured. French losses were not reported but were probably light.[8] Meanwhile, to the northeast of Warsaw, General of Division Anne Jean Marie René Savary's V Corps defeated Lieutenant General Ivan Essen at the Battle of Ostroleka on 16 February. The French lost 1,171 casualties including one general killed. Russian losses were 2,500 soldiers, seven guns, and two colors.[9]

At the end of March 1807, Marshal Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier withdrew many of his troops from the Siege of Stralsund with the intention of using them for the Siege of Kolberg. His Swedish opponent, General-Leutnant Hans Henric von Essen immediately pushed back the outnumbered besiegers. Quickly returning with the bulk of his soldiers, Mortier drove the Swedes north of the Peene River and the two sides concluded an armistice on 29 April. This freed many of Mortier's troops for other duties and allowed Napoleon to concentrate on reducing Gdańsk (Danzig).[10]

Marshal François Joseph Lefebvre invested the fortress of Danzig on 10 March 1807. After a prolonged defense in the Siege of Danzig, General of Infantry Friedrich Adolf, Count von Kalckreuth surrendered on 24 May. Of the 370 officers and 15,287 men of the garrison, 3,000 were killed, wounded, or died of disease. French losses numbered about 6,000 killed, wounded, or died of sickness. French officer casualties were 28 killed and 105 wounded.[11] On the 27th, the garrison marched out with the honors of war and were escorted to Baltiysk (Pillau). The paroled Prussians promised not to fight against France for one year.[12]

Battle

Plans

With Danzig secured in his rear, Napoleon planned to launch an offensive around 10 June. When he received intelligence that the Russians intended to attack him, the emperor thought the enemy move "ridiculous" since they had done little to trouble him while Danzig was under siege.[13] By this time, Napoleon massed 220,000 troops in Poland against only 115,000 Russians and Prussians.[14] Napoleon had 190,000 men under his direct command while Marshal André Masséna commanded the rest.[15] Masséna's instructions were to cover Warsaw, guard the right wing, and threaten the Russian strategic left flank.[16]

On 2 June Bennigsen concentrated his army at Heilsberg and advanced on Napoleon's lines. The Russian commander planned to destroy Ney's exposed corps in an overly complex operation involving six advancing columns. He sent the 1st Column with 24 battalions and 4 batteries through Orneta (Wormditt), then south, to drive the French troops from the east bank of the Pasłęka. The Russians would then move south and take position near Eldyty Wielkie (Elditten), thus preventing Soult from supporting Ney. Dokhturov commanded the 1st Column, which included his own 4,653-man 7th Division and Lieutenant General Peter Kirillovich Essen's 5,670-strong 8th Division.[15]

Lieutenant General Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken led the 2nd Column, which consisted of 42 battalions, 140 squadrons, and nine batteries. Bennigsen desired the 2nd Column to strike Ney's left flank while supporting the adjacent 1st and 3rd Columns. Osten-Sacken commanded his own 6,432-man 3rd Division, Lieutenant General Alexander Ivanovich Ostermann-Tolstoy's 9,615-strong 2nd and 14th Divisions, the 3,836 troopers of Major General Fedor Petrovich Uvarov's right wing cavalry, and the 2,982 horsemen of Lieutenant General Dmitry Golitsyn's left wing cavalry.[15] Lieutenant General Pyotr Bagration directed the 3rd Column of 42 battalions, 10 squadrons, and six regiments of cossacks. This column, which was composed of the army Advance Guard, would attack north of Guttstadt with the aim of cutting off some of Ney's troops. Bagration's 3rd Column numbered 12,537 troops.[17]

Lieutenant General Aleksey Gorchakov exercised authority over the 4th Column, a body made up of the 6th Division with 12 battalions, 20 squadrons, and three regiments of cossacks. Gorchakov was ordered to cross the Łyna (Alle) River south of Guttstadt and attack Ney's right flank. The 6th Division was 10,873 strong. The 6,347-man 5th Column was entrusted to Major General Matvei Platov. Supported by Major General Bogdan von Knorring's 6th Division brigade, this column would cross the Łyna at Bergfriede (Barkweda) and try to envelop Ney's right flank. Platov led three battalions, 10 squadrons, and nine regiments of cossacks. Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich of Russia directed the 6th Column, consisting of the 1st Imperial Guard Division. Constantine's force, which constituted the army reserve, included 28 battalions, 28 squadrons, and three batteries, a total of 17,000 soldiers.[17]

Bennigsen instructed L'Estocq to move against the French I Corps, which deployed along the lower reaches of the Pasłęka. While guarding the road to Königsberg, the Prussian general would drive Bernadotte's men onto the west bank and pin them there. L'Estocq commanded about 20,000 men and 78 guns, of whom 15,000 were Prussians. The Russian contingent was led by Lieutenant General Nikolay Kamensky. Finally, Lieutenant General Pyotr Aleksandrovich Tolstoy with 15,800 soldiers kept Masséna's right wing under observation northeast of Warsaw.[17]

Because Ney's front was screened by forests, Bennigsen had a reasonable hope that he could fall on the Frenchman's troops before his opponent could take effective countermeasures. In the event, French scouts picked up enough information for Ney to order a concentration between Guttstadt and Deppen. He also sent a message to Soult asking him to hold Elditten on his left and another to Davout requesting him to defend Bergfriede on his right.[18]

Spanden

Bennigsen's original orders called for the attack to begin on 4 June. Accordingly, L'Estocq assembled General-Major Michael Szabszinski von Rembow's division at Pieniężno (Mehlsack). On the morning of the 4th, Rembow moved to southwest to Spanden where he began to attack Bernadotte's bridgehead. Unknown to the Prussian general, Bennigsen had postponed the offensive by one day and the new orders had not been properly transmitted. Dokhturov at Wormditt heard cannon fire and sent Rembow a note asking the reason. Apprised of his error, the Prussian withdrew his division, but Bernadotte was thoroughly alerted by the day's events.[19]

At 10:00 AM on 5 June, Rembow attacked General of Division Eugene-Casimir Villatte's division at Spanden. The Prussian general commanded as few as 3,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry,[19] or as many as 6,000 troops. He had three battalions each of the Sievsk and Perm Russian Infantry Regiments, ten squadrons of the Ziethen Dragoon Regiment Nr. 6, five squadrons of the Baczko Dragoon Regiment Nr. 7, 29 cannons, and two howitzers. Villatte directed General of Brigade Bernard-Georges-François Frère's brigade, two battalions each of the 27th Light and the 63rd Line Infantry Regiments, plus three squadrons each of the 17th and 19th Dragoon Regiments.[1] The 63rd was one of the units transferred from the VII Corps.[20]

The French fortified a loop in the Pasłęka that formed a re-entrant toward the west bank of the stream. By closing off the east end of the loop with a central redoubt connected by earthworks to the river banks on each side, the French held a well-protected east bank bridgehead. A second redoubt near the bridge provided a backup position.[19] Villatte deployed the 27th Light in the bridgehead, with the 63rd Line and 17th Dragoons in direct support on the west bank. His second brigade under General of Brigade Jean-Baptiste Girard held the line of the Pasłęka farther north with the 94th and 95th Line Infantry Regiments. The 18th, 19th, and 20th Dragoon Regiments were with Girard.[21]

L'Estocq's instructions called for him to mount a demonstration against Bernadotte's position. However, his adjutant Major Saint-Paul convinced him to order a full-scale assault.[1] After the Spanden bridgehead was pounded by artillery for two hours, Rembow's Russian infantry advanced to the attack. The 27th Light Infantry, supported by four cannons and one howitzer, waited until the Russians were within close range before blasting them with a series of volleys. Shattered by the deadly fire, the Russians ran away, chased by the 17th Dragoons. L'Estocq admitted losing 500 killed and wounded, while the French claimed to have inflicted 700 to 800 casualties. The only French loss of consequence was Bernadotte, who was wounded in the head by a bullet and had to hand over command of the I Corps to General of Division Claude Perrin Victor. Also on the 5th, General of Division Pierre Dupont de l'Étang repelled a Prussian probe near Braunsberg.[21]

Lomitten

At 6:00 AM on the 5th, Dokhturov began driving in Soult's outposts after marching southwest from Wormditt via Wojciechowo (Albrechtsdorf). General of Division Claude Carra Saint-Cyr's division of the IV Corps defended the Lomitten bridgehead. Two redoubts which stood on the east bank of the Pasłęka were connected by a line of breastworks. These fieldworks were defended by the 1st Battalion of the 57th Line Infantry Regiment and four cannons. Off to the left, the 2nd Battalion of the 57th defended a wooded area surrounded by abatis. One battalion of the 24th Light Infantry Regiment held the west bank in direct support, while a second battalion of the 24th Light watched the river farther north at Podągi (Sporthenen) and Olkowo (Alken). Carra Saint-Cyr posted the rest of his division to the rear near Miłakowo (Liebstadt)[22]

Dokhturov launched three attack columns at the French works at 8:00 AM on 5 June. At about the same time, a detachment of Russian cavalry crossed the Pasłęka near Sporthenen and a force of infantry and artillery probed at Alken. The battalion of the 24th Light charged the Russians at Sporthenen and drove them back to the east bank. Meanwhile, at Lomitten, Dokhturov's troops fought their way through the abatis in their initial rush only to be thrown back. They charged again and nearly captured the wood when Carra Saint-Cyr's reinforcements arrived and restored the line. The 2nd/57th reoccupied the wood and held it for four hours.[22]

By this time, single battalions of the 46th Line and 24th Light were committed to defend the Lomitten bridgehead. The action lasted eight hours, at the end of which, the Russians attempted to storm the position in one massive column. This assault came to naught when two French battalions counterattacked. Orders arrived from Soult permitting Carra Saint-Cyr to evacuate the bridgehead. Since the Russian artillery had nearly leveled the earthworks and set the village of Lomitten on fire, the division commander exercised his discretion and pulled back. Even so, the French still blocked the bridge and the Russians fell back toward Wormditt at 8:00 PM.[23]

The French reported losing 106 killed and 1,079 wounded, and claimed that they inflicted 800 killed and 2,000 wounded on the Russians. Historian Digby Smith called the action a Russian victory.[1] While part of his command battered at Lomitten, Dokhturov took the rest south to the bridge near Elditten. The local French commander, General of Division Louis-Vincent-Joseph Le Blond de Saint-Hilaire defended the crossing in strength and the Russian leader did not try to attack.[23]

Guttstadt-Deppen

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Ney deployed General of Division Jean Gabriel Marchand's division at Guttstadt and Praslity (Altkirch) to the north, with one infantry and one cavalry regiment in the woods near Smolajny (Schmolainen). The French marshal posted General of Division Baptiste Pierre Bisson's division to the south and west in the villages of Głotowo (Glottau), Knopin (Knopen), Łęgno (Lingnau), and Kwiecewo (Queetz).[24] Marchand commanded the 6th Light, 39th Line, 69th Line, and 76th Line Infantry Regiments. Bisson led the 25th Light, 27th Line, 50th Line, and 59th Line Infantry Regiments. All regiments were made up of two battalions. A powerful cavalry contingent supported VI Corps, including the 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 8th Hussar Regiments, the 14th and 24th Chasseurs a Cheval Regiments, and the 12th Dragoon Regiment. All cavalry regiments had three squadrons except the dragoons, which had four. Bennigsen's 63,000 troops massively outnumbered Ney, who counted only 17,000 men.[1] The Polish 3rd Infantry Regiment under Colonel Edward Żółtowski and 5th Mounted Rifles Regiment under Colonel Kazimierz Turno also took part in the battle on the side of Napoleon.[25]

At 6:00 AM on 5 June, Bagration advanced on Altkirch and quickly captured it. At Altkirch, the Advance Guard commander hesitated because the 2nd and 4th Columns were lagging behind schedule. Ney used the chance to pull back the troops at Schmolainen, while launching a powerful riposte on Bagration. The Russians lost 500 casualties in the encounter, while French losses are not stated. As Osten-Sacken's strong 2nd Column began to make itself felt on his left, Ney made a fighting withdrawal, making maximum use of skirmishers.[24]

Gorchakov seized Guttstadt after the French evacuated it. Platov got across the Łyna at Barkweda and joined the Russian left wing. By 3:00 PM, Ney took up a position facing northeast near Jankowo (Ankendorf) and Świątki (Heiligenthal). The right flank was protected by the Queetz Lake, the center by a small watercourse, and the left flank by a small forest north of Deppen. The day's action ended along this line.[26]

The morning of 6 June found Ney still defiantly in position. The Russian attacks began at 5:00 AM with Golitsyn attacking the French left, hoping to seize the bridge at Deppen and cut off Ney's retreat. Osten-Sacken assaulted the French center while Gorchakov struck his opponents' right flank. Bennigsen held Bagration's Advanced Guard and Constantine's Guard in reserve. Ney's defense completely baffled Gorchakov, but his left and center were relentlessly pressed back. Hoping to flank Ney out of position, Gorchakov moved south of Queetz Lake[26] which is about 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) south of Queetz.[note 1] and took his soldiers out of the battle for a few hours. This blunder relieved the pressure on the French right and the marshal used the respite to shift troops to shore up his left and center. Neatly withdrawing his corps across the bridge at Deppen, Ney escaped with little further loss.[27]

Aftermath

Digby Smith credited the Russians with a victory at Guttstadt and Deppen.[1] However, Bennigsen became so enraged at his failure to crush Ney that he vented his anger on Osten-Sacken,[28] who he claimed, had ignored repeated orders to attack.[29] Smarting from his ill-treatment, Osten-Sacken left the army for a short time.[28] According to their official bulletins,[30] the French lost 400 killed or wounded and 250 captured, along with two guns and the VI Corps baggage train. The Russians captured 73 officers and 1,568 men, including General of Brigade François Roguet;[1] 2,000 French were claimed to have been killed.[31] Bennigsen lost some 2,000 men killed or wounded,[26][32] including Ostermann-Tolstoy and Lieutenant General Andrei Andreievich Somov among the wounded.[29][32]

That evening, Bennigsen set up his headquarters at Heilingenthal with the bulk of his army nearby. Gorchakov took position at Guttstadt, while L'Estocq and Kamensky hovered in the vicinity of Mehlsack. According to historian Francis Loraine Petre, the Russian "offensive had expended its force and come to a standstill". Napoleon immediately began assembling his forces for a counteroffensive.[28] Bennigsen ordered his army to retreat on the evening of 7 June.[33] The Russian commander repulsed Napoleon at the Battle of Heilsberg on 10 June.[29] But at Friedland the French emperor won the decisive battle of the war on 14 June 1807, which led to the Peace of Tilsit.[34]

Notes

- Footnotes

- The lake, which appears to have dried up, can be seen on Google Earth.

- Citations

- Smith, 246

- Гутштадт // Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary. Vol. 18 (1893): "Гравилат — Давенант", p. 945

- Petre, 219-220

- Chandler Campaigns, 550

- Petre, 222

- Chandler Campaigns, 551

- Petre, 227

- Smith, 244

- Smith, 243

- Petre, 265

- Smith, 245

- Petre, 260

- Petre, 273

- Chandler Campaigns, 564-565

- Petre, 275-276

- Petre, 269

- Petre, 275 & 277

- Petre, 277

- Petre, 278

- Chandler Jena, 37

- Petre, 279

- Petre, 280

- Petre, 281

- Petre, 282

- Gembarzewski, Bronisław (1925). Rodowody pułków polskich i oddziałów równorzędnych od r. 1717 do r. 1831 (in Polish). Warszawa: Towarzystwo Wiedzy Wojskowej. pp. 53–54, 60.

- Petre, 283

- Petre, 283-284

- Petre, 284

- Smith, 247

- Davis J. Eighteen Original Journals of the Eighteen Campaigns of the Emperor Napoleon: Being Those in which He Personally Commanded in Chief. 1817. V. II. P. 179

- Wilson R. Brief Remarks on the Character and Composition of the Russian Army and a Sketch of the Campaigns in Poland in the Years 1806 and 1807. Egerton, 1810. P. 249

- Summerville Ch. J. Napoleon's Polish Gamble: Eylau and Friedland 1807. Pen & Sword Military, 2005. P. 117

- Petre, 286

- Chandler Campaigns, 582

References

- Chandler, David G. Jena 1806: Napoleon Destroys Prussia. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2005. ISBN 0-275-98612-8

- Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Macmillan, 1966. OCLC 401930

- Petre, F. Loraine. Napoleon's Campaign in Poland 1806-1807. London: Lionel Leventhal Ltd., 1976 (1907).

- Smith, Digby. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill, 1998. ISBN 1-85367-276-9

External links

The following websites are good sources for the full names of French, Russian, and Prussian generals.

- Broughton, Tony. napoleon-series.org Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1792-1815

- Millar, Stephen. napoleon-series.org Russian-Prussian Order of Battle at Eylau: 8 February 1807

- (in German) Montag, Reinhard. lexikon-deutschegenerale.de Lexikon der Deutschen Generale

Media related to Battle of Guttstadt-Deppen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Guttstadt-Deppen at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Mileto |

Napoleonic Wars Battle of Guttstadt-Deppen |

Succeeded by Battle of Heilsberg |