Battle of Maldon

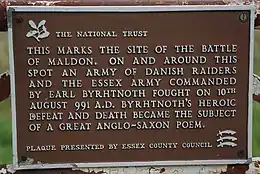

The Battle of Maldon took place on 11 August 991 AD[2] near Maldon beside the River Blackwater in Essex, England, during the reign of Æthelred the Unready. Earl Byrhtnoth and his thegns led the English against a Viking invasion. The battle ended in an Anglo-Saxon defeat. After the battle Archbishop Sigeric of Canterbury and the aldermen of the south-western provinces advised King Æthelred to buy off the Vikings rather than continue the armed struggle. The result was a payment of Danegeld of 10,000 Roman pounds (3,300 kg) of silver (approx £1.8M at 2022 prices).

| Battle of Maldon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Viking invasions of England | |||||||

.jpg.webp) Alfred Pearseː Battle of Maldon in 991 (Hutchinson's Story of the British Nation, 1922) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| England | Vikings | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Byrhtnoth † | Olaf, possibly Olaf Tryggvason | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | 2,000–4,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Location within England | |||||||

An account of the battle, embellished with many speeches attributed to the warriors and with other details, is related in an Old English poem which is usually named The Battle of Maldon. A modern embroidery created for the millennium celebration in 1991 and, in part, depicting the battle, can be seen at the Maeldune Centre in Maldon.

One manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that a certain Olaf, possibly the Norwegian Olaf Tryggvason, led the Viking forces, these estimated to have been between 2,000 and 4,000 fighting men. A source from the 12th-century Liber Eliensis, written by the monks at Ely, suggests that Byrhtnoth had only a few men to command: "he was neither shaken by the small number of his men, nor fearful of the multitude of the enemy". Not all sources indicate such a disparity in numbers.

The poem "The Battle of Maldon"

"The Battle of Maldon" is the name conventionally given to a surviving 325-line fragment of Old English poetry. Linguistic study has led to the conjecture that initially the complete poem was transmitted orally, then in a lost manuscript in the East Saxon dialect and now survives as a fragment in the West Saxon form, possibly that of a scribe active at the Monastery of Worcester late in the 11th century.[3] It is fortuitous that this was attached at an early date to a very notable manuscript, Asser's Life of King Alfred, which undoubtedly assisted in its survival. The manuscript, by now detached, was burned in the Cotton library fire at Ashburnham House in 1731. The keeper of the collection, John Elphinstone (or his assistant, David Casley),[4] had transcribed the 325 lines of the poem in 1724, but the front and back pages were already missing from the manuscript (possibly around 50 lines each): an earlier catalogue described it as fragmentum capite et calce mutilatum ('mutilated at head and heel'). As a result, vital clues about the purpose of the poem and perhaps its date have been lost.

At the time of battle, English royal policy of responding to Viking incursions was split. Some favoured paying off the Viking invaders with land and wealth, while others favoured fighting to the last man. The poem suggests that Byrhtnoth held this latter attitude, hence his moving speeches of patriotism.

The Vikings sailed up the Blackwater (then called the Panta), and Byrhtnoth called out his levy. The poem begins with him ordering his men to stand and to hold weapons. His troops, except for personal household guards, were local farmers and villagers of the Essex Fyrd militia. He ordered them to "send steed away and stride forwards": they arrived on horses but fought on foot. The Vikings sailed up to a small island in the river. At low tide, the river leaves a land bridge from this island to the shore; the description seems to have matched the Northey Island causeway at that time. This would place the site of the battle about two miles southeast of Maldon. Olaf addressed the Saxons, promising to sail away if he was paid with gold and armour from the lord. Byrhtnoth replied, "We will pay you with spear tips and sword blades."

With the ebb of the tide, Olaf's forces began an assault across the small land bridge. Three Anglo-Saxon warriors, Wulfstan, Ælfhere and Maccus blocked the bridge, successfully engaging any Vikings who pressed forward (lines 72–83). The Viking commander requested that Byrhtnoth allow his troops onto the shore for formal battle. Byrhtnoth, for his ofermōde (line 89b), let the enemy force cross to the mainland. Battle was joined, but an Englishman called Godrīc fled riding Byrhtnoth's horse. Godrīc's brothers Godwine and Godwīg followed him. Then many English fled, recognizing the horse and thinking that its rider was Byrhtnoth fleeing. To add insult to injury, it is stated that Godric had often been given horses by Byrhtnoth, a detail that, especially during the time period, would have had Godric marked as a coward and a traitor, something that could have easily been described as worse than death. The Vikings overcame the Saxons after losing many men, killing Byrhtnoth. After the battle Byrhtnoth's body was found with its head missing, but his gold-hilted sword was still with his body.

There is some discussion about the meaning of "ofermōd". Although literally meaning "over-heart" or "having too much heart", it could mean either "pride" or "excess of courage" (compare the Danish overmod or German Übermut, which mean both "hubris" and "recklessness"). One argument is that the poem was written to celebrate Byrhtnoth's actions and goad others into heroic action, and Byrhtnoth's action stands proudly in a long tradition of heroic literature. Another viewpoint, most notably held by J. R. R. Tolkien, is that the poem is an elegy on a terrible loss and that the monastic author pinpoints the cause of the defeat in the commander's sin of pride, a viewpoint bolstered by the fact that ofermōd is, in every other attested instance, used to describe Satan's pride.[5] There is a memorial window, representing Byrhtnoth's dying prayer, in St Mary's church at Maldon.

It is believed by many scholars that the poem, while based upon actual events and people, was created to be less of a historical account and more of a means of enshrining and lifting up the memories of the men who fought and lost their lives on the battlefield protecting their homeland, especially in the case of the English commander of the battle, Byrhtnoth. He (Byrhtnoth) seems to embody many of the virtues that are uplifted in the Anglo-Saxon world, and is compared often by many scholars to the character Beowulf.

Norse invaders and Norse raiders differed in purpose. The forces engaged by the Anglo-Saxon were raiding, or (in Old Norse) "í víking", to gather loot, rather than to occupy land for settlement. Therefore, if Byrhtnoth's forces had kept the Vikings off by guarding the causeway or by paying them off, Olaf would likely have sailed farther up the river or along the coast, and raided elsewhere. As a man with troops and weapons, it might be that Byrhtnoth had to allow the Vikings ashore to protect others. The poem may, therefore, represent the work of what has been termed the "monastic party" in Ethelred's court, which advocated a military response, rather than tribute, to all Norse attacks.

Other sources

The death of Byrhtnoth, an ealdorman of Essex, was recorded in four versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Its Cotton Tiberius manuscript (Version B) says for the year 991:

Her wæs Gypeswic gehergod, ⁊ æfter þæm swyðe raþe wæs Byrihtnoð ealdorman ofslagan æt Meldune. ⁊ on þam geare man gerædde þæt man geald ærest gafol Deniscum mannum for þam myclan brogan þe hi worhton be þam særiman, þæt wæs ærest .x. þusend punda. Þæne ræd gerædde ærest Syric arcebisceop. |

Here Ipswich was raided. Very soon after that, ealdorman Byrhtnoth was killed at Maldon. And on that year it was decided to pay tax to Danes for the great terror which they made by the sea coast; that first [payment] was 10,000 pounds. Archbishop Sigerīc decided first on the matter. |

The Life of Oswald, written in Ramsey around the same time as the battle, portrays Byrhtnoth as a great religious warrior, with references to Biblical prophetic era figures.[6]

In 1170, the Liber Eliensis retold and embroidered the story and made the battle two fights, with the second being a fortnight long against overwhelming odds. These texts show, to some degree, the growth of a local hero cultus.

Chronology

The Winchester (or Parker) version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Version A), has the most detailed account of the battle, but places it under the heading for the year 993. As all the other versions of the Chronicle place it in 991, this is believed to be either a transcription error, or because the battle was inserted later when its importance had become apparent. The widely accepted precise date is taken from notices for the death of Byrhtnoth in three abbey calendars; those of Ely, Winchester and Ramsey. The date in the Ely calendar is 10 August, whereas Winchester and Ramsey give 11 August. However, Byrhtnoth's close connections with Ely imply that 10 August is more likely to be the accurate date.[7]

Topography

It is clear from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles that Maldon in Essex is the site of the battle, because of its proximity to Ipswich and because Byrhtnoth was an Ealdorman of Essex.[8] More precise details come from The Battle of Maldon narrative, which describes how the Vikings established themselves on an island, separated from the mainland by a tidal inlet which could be crossed by a "bridge" or "ford" at low tide. The poem describes how the Vikings and Saxons negotiated by calling across the water while waiting for the tide to go out. Northey Island seems to fit this description. An investigation in 1973 suggested that the channel between Northey Island and the mainland would have been about 120 yards (110 metres) rather than 240 yards (220 metres) today. The causeway which crosses the channel today may not have existed in its present form in the 10th century, but there was certainly some form of crossing present. Other sites have been suggested, one being Osea Island which can be reached by a causeway, but is too far from the mainland to shout across. A bridge a mile inland from Maldon, now called Heybridge, has also been suggested, but the river is not tidal at that point.[9]

Manuscript sources

In the Cotton library, the "Battle of Maldon" text had been in Otho A xii. The Elphinstone transcription is in the Bodleian Library, where it is pp. 7–12 of MS Rawlinson B. 203.

References

- "The Battle of Maldon sometimes called Byrhtnoth's Death". Barry Sharples’ Miscellany Website.

- "The Battle of Maldon – Introduction".

- E. V.Gordon, The Battle of Maldon (London, 1968) p. 38

- Fulk, Robert; Cain, Christopher (2003). A history of Old English literature. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-6312-2397-9.

- Tolkien's Heroic Criticism: A Developing Application Of Anglo-Saxon Ofermod To The Monsters Of Modernity Archived 13 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. 2003. Rorabeck, Robert. Thesis, Florida State University.

- "Life of Saint Oswald – Information from The UK Battlefields Resource Centre". www.battlefieldstrust.com. The Battlefields Trust. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- "English Heritage Battlefield Report: Maldon 991" (PDF). historicengland.org.uk. English Heritage. 1995. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Foard, Glenn (10 September 2003). "Maldon Battle and Campaign" (PDF). UK Battlefields Resource Centre. The Battlefields Trust. p. 18. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- English Heritage Battlefield Report, pp. 2–4

- Bibliography

- Gordon, E.V. (1968). The Battle of Maldon. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - S. A. J. Bradley, ed. (1982). Anglo-Saxon poetry: an anthology of Old English poems. London: Dent.

- Santoro, Verio (2012). La ricezione moderna della Battaglia di Maldon: Tolkien, Borges e gli altri. Roma: Aracne.

- Editions and translations

- Foys, Martin et al. Old English Poetry in Facsimile Project, Madison, 2019; edited with digital images of its manuscript and early print pages, and translated.

External links

- Modern English text of The Battle of Maldon poem, trans. by Wilfred Berridge from the Battle of Maldon.org.uk website

- Old English text of the Battle of Maldon poem

- The Battle of Maldon, with photograph of the famous causeway

- James Grout: The Battle of Maldon, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Battle of Maldon Battlefields Trust London and South East article. Contains some discussion of the aftermath and consequences of the battle.

- Derek Punchard The Battle of Maldon from the Maeldune website

- Alexander M. Bruce Maldon and Moria: on Byrhtnoth, Gandalf, and heroism in The Lord of the Rings Article from "Mythlore", 22 September 2007.

- Giles, J A, ed. (1914). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: G Bell & Sons Ltd. p. 87. (the entry for the year 991 in modern English).