Battle of Paris (1814)

The Battle of Paris (or the Storming of Paris[2]) was fought on 30–31 March 1814 between the Sixth Coalition, consisting of Russia, Austria, and Prussia, and the French Empire. After a day of fighting in the suburbs of Paris, the French surrendered on March 31, ending the War of the Sixth Coalition and forcing Emperor Napoleon to abdicate and go into exile.

| Battle of Paris | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Campaign of France of the Sixth Coalition | |||||||||

The Defense of Clichy during the battle | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 29,000-42,000[1] |

Russia: 100,000 Austria: 15,000 Prussia: 40,000 Total: 100,000[1]-155,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 5,000-9,300[1] killed, wounded or captured | 9,000[1]-18,000 killed, wounded or captured | ||||||||

Location within France | |||||||||

Background

Napoleon was retreating from his failed invasion of Russia in 1812. With the Russian armies following up victory, the Sixth Coalition was formed with Russia, Austria, Prussia, Portugal, Great Britain, Sweden, Spain and other nations hostile to the French Empire. Even though the French were victorious in the initial battles during their campaign in Germany, the Coalition armies eventually joined and defeated them at the Battle of Leipzig in the autumn of 1813. After the battle, the Pro-French German Confederation of the Rhine collapsed, thereby loosening Napoleon's hold on Germany east of the Rhine. The Coalition forces in Germany then crossed the Rhine and invaded France.

Prelude

Campaign in northeastern France

The Coalition forces, numbering more than 400,000 and divided into three groups, finally entered northeastern France in January 1814. Facing them in the theatre were 70,000 Frenchmen, but they had the advantage of fighting in friendly territory, shorter supply lines, and more secure lines of communication.

Utilizing his advantages, Napoleon defeated the divided Coalition forces in detail, starting with the battles at Brienne and La Rothière, but could not stop the latter's advance. He then launched his Six Days' Campaign against the Coalition army under Blücher, which was threatening Paris from the northeast at the river Aisne. He successfully defeated and halted it, but Napoleon failed to seize the strategic initiative back in his favor, as Blücher's forces were still largely intact.

Meanwhile, shifting his forces from the Aisne to this sector, Napoleon and his army engaged another Coalition army, under Schwarzenberg, which was also threatening Paris, this time from the southeast, near the Aube, at the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube on 20 March. He was successful in defeating this army, but it was not enough to halt it in time, as it later linked up with Blücher's army at Meaux on 28 March. After this, the Coalition forces advanced yet again towards Paris.

Until this battle it had been nearly 400 years since a foreign army had entered Paris, during the Hundred Years' War.

French war-weariness

Since the disaster in Russia and the start of the war, the French populace had become increasingly war-weary.[3] France had been exhausting itself at war for 25 years, and many of its men had died during the wars Napoleon had fought until then, making conscription there increasingly unpopular. Once the Coalition forces entered the country of France, the leaders were astonished and relieved upon seeing that against their expectations and fears the populace never staged a popular uprising against them, in the scale of the popular guerrilla war in Spain or Russia's patriotic resistance against the Grande Armée in 1812. Even Napoleon's own ex-foreign minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, sent a letter to the Coalition monarchs stating that the Parisians were already becoming angry against their Emperor and would even welcome the Coalition armies if they were to enter the city.

Tsar Alexander's subterfuge

.jpg.webp)

The leaders of the Coalition decided that Paris and not Napoleon himself was now the main objective. For the plan, some generals proposed their respective plans, but one, that of the Russian general Toll, fit precisely what Tsar Alexander I had in mind: attack Paris head-on with the main Coalition army while Napoleon was redirected as far away from the city as possible.

The Tsar intended to ride out to meet the Prussian king and Schwarzenberg. They met on a road leading directly to Paris and the Tsar proposed his intentions. He brought a map and spread it to the ground for all of them to see as they talked about the plan. The plan was for the entire main Coalition army to stop pursuing Napoleon and his army and instead march directly to Paris. The exception was Wintzingerode's 10,000-strong cavalry detachment and eight horse batteries which were to follow and mislead Napoleon that the Coalition army was still pursuing him southwards. As usual, the king and Schwarzenberg agreed. The main Coalition army began its march towards Paris on 28 March, and on the same day, Wintzingerode's unit was now performing his task.

The deception campaign worked. While the main Coalition army attacked Paris, Wintzingerode's unit hotly pursued Napoleon and his conscripted ragtag army to the southeast, until Napoleon's forces regrouped and counter-attacked. However, by the time Napoleon saw through the subterfuge, he was already too far away to the southeast of Paris, which was now faced with Coalition forces, and Napoleon would never reach Paris in time. Completely out of position, he could not participate in the upcoming battle and fall of Paris.

Forces

.jpg.webp)

The Austrian, Prussian and Russian armies were joined and put under the command of Field Marshal Count Barclay de Tolly who would also be responsible for the taking of the city, but the driving force behind the army was the Tsar of Russia together with the King of Prussia, moving with the army. The Coalition army totaled about 150,000 troops, most of whom were seasoned veterans of the past campaigns. Napoleon had left his brother Joseph Bonaparte in defense of Paris with about 23,000 regular troops under Marshal Auguste Marmont, although many of them were young conscripts, along with an additional 6,000 National Guards and a small force of the Imperial Guard under Marshals Bon Adrien Jeannot de Moncey and Édouard Mortier. Assisting the French were the incomplete trenches and other defenses in and around the city.

Battle

The Coalition army arrived outside Paris in late March. Nearing the city, Russian troops broke rank and ran forward to get their first glimpse of the city. Camping outside the city on March 29, the Coalition forces were to assault the city from its northern and eastern sides the next morning on March 30. The battle started that same morning with intense artillery bombardment from the Coalition army. Early in the morning the Coalition attack began when the Russians attacked and drove back the French skirmishers near Belleville[4] before themselves driven back by French cavalry from the city's eastern suburbs. By 7:00 a.m. the Russians attacked the Young Guard near Romainville in the center of the French lines and after some time and hard fighting pushed them back. A few hours later the Prussians, under Blücher, attacked north of the city and carried the French position around Aubervilliers, but did not press their attack.

The Württemberg troops seized the positions at Saint-Maur to the southeast, with Austrian troops in support. The Russians attempted to press their attack but became caught up by trenches and artillery before falling back before a counterattack of the Imperial Guard. The Imperial Guard continued to hold back the Russians in the center until the Prussian forces appeared to their rear.

The Russian Imperial Guard and the Prussian Life Guards under Alexey P. Yermolov then assailed the Montmartre Heights in the city's northeast, where Joseph's headquarters had been at the beginning of the battle, which was defended by Brigadier-general Baron Christiani. Control of the heights was severely contested. The Prussian guardsmen suffered heavy losses, but the heights eventually remained in the Allied hands, there Yermolov placed an artillery battery. Joseph fled the city. Marmont contacted the Coalition and reached a secret agreement with them. Shortly afterwards, he marched his soldiers to a position where they were quickly surrounded by Coalition troops; Marmont then surrendered, as had been agreed.

Aftermath

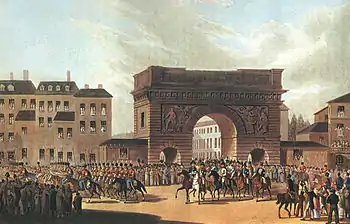

(Painted by François Bouchot in 1843)

Alexander sent an envoy to meet with the French to hasten the surrender. He offered generous terms to the French and, although willing to avenge the destruction of Moscow more than a year earlier, declared himself to be bringing peace to France rather than its destruction. On March 31 Talleyrand gave the key of the city to the Tsar. Later that day the Coalition armies triumphantly entered the city with the Tsar at the head of the army followed by the King of Prussia and Prince Schwarzenberg. On April 2, the Senate passed the Acte de déchéance de l'Empereur ("Emperor's Demise Act"), which declared Napoleon deposed.

Napoleon had advanced as far as Fontainebleau when he heard that Paris had surrendered. Outraged, he wanted to march on the capital, but his marshals would not fight for him and repeatedly urged him to surrender. He abdicated in favour of his son on April 4. The Allies rejected this out of hand, forcing Napoleon to abdicate unconditionally on April 6.

The terms of his abdication, which included his exile to the Isle of Elba, were settled in the Treaty of Fontainebleau on 11 April 1814. A reluctant Napoleon ratified it two days later.

The War of the Sixth Coalition was over but the Hundred Days started on 20 March 1815 in Paris.

See also

- Military career of Napoleon Bonaparte

- Parizh, a Cossack settlement named to honour the battle.

- Freiwilliges Feldjäger-Korps von Schmidt

- Medal "For the Capture of Paris", Russian decoration for those who participated in the action.

Notes

- Bodart 1908, p. 480.

- Velichko et al. 1912.

- Merriman 1996, p. 579.

- Mikhailofsky-Danilefsky 1839, p. 356.

References

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618-1905). Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- Merriman, John (1996). A History of Modern Europe. W. W. Norton. p. 579. ISBN 0-393-96888-X.

- Mikhailofsky-Danilefsky, A. (1839). History of the Campaign in France (Thesis). London: Smith, Elder, and Co. Cornhill.

- Velichko, Konstantin I.; Novitsky, Vasily F.; Schwarz, Aleksey V. von; Apushkin, Vladimir A.; Schoultz, Gustav K. von (1912). Военная энциклопедия Сытина [Sytin Military Encyclopedia] (in Russian). Vol. VII: Воинская честь — Гимнастика военная. Moscow: Типография Т-ва И. Д. Сытина. pp. 96–97. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

Further reading

- Compton's Home Library: Battles of the World CD-ROM

External links

- Battle of Paris 1814, maps, illustrations

Media related to Battle of Paris (1814) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Paris (1814) at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Saint-Dizier |

Napoleonic Wars Battle of Paris (1814) |

Succeeded by Battle of Toulouse (1814) |