Battle of Ngomano

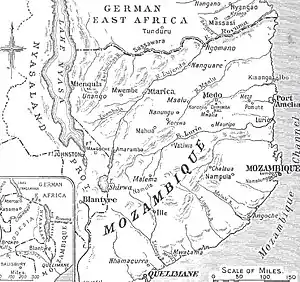

The Battle of Ngomano or Negomano was fought between Germany and Portugal during the East African Campaign of World War I. A force of Germans and Askaris under Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck had recently won a costly victory against the British at the Battle of Mahiwa, in present-day Tanzania and ran very short of food and other supplies. As a consequence, the Germans invaded Portuguese East Africa to the south, both to supply themselves with captured Portuguese materiel and escape superior British forces to the north.

| Battle of Ngomano | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of East African Campaign | |||||||

Breakthrough of the Schutztruppe at the Rovuma | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,500–2,000 men | 900 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

4 killed Few wounded |

200 killed and wounded[2] 700 captured | ||||||

Portugal was part of the Entente and a belligerent, employing troops in France and Africa; so a force under Major João Teixeira Pinto was sent to stop von Lettow-Vorbeck from crossing the border. The Portuguese were flanked by the Germans, while encamped at Ngomano on 25 November 1917. The battle saw the Portuguese force nearly destroyed, with many troops killed and captured. The capitulation of the Portuguese enabled the Germans to seize a large quantity of supplies and continue operations in East Africa until the end of the war.

Background

By late November 1917, the Germans in East Africa were left with few options if they wanted to continue the war. They were outnumbered drastically and were split up into several different columns. The two largest of these, under Theodor Tafel and Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, were completely cut off from each other. Although von Lettow-Vorbeck's column had defeated a large British force at the Battle of Mahiwa he had lost a large number of troops and expended virtually his entire supply of modern ammunition. With only antiquated weapons and no means of resupply, von Lettow-Vorbeck decided to invade Portuguese East Africa in hopes of acquiring sufficient supplies to continue the war.[3] There was no legal impediment to this attack; acting at Britain's request, Portugal had seized 36 German and Austro-Hungarian merchant ships anchored in front of Lisbon on 24 February 1916 and Germany had declared war on Portugal on 9 March 1916.[4]

Although Tafel's force was intercepted by the Allies and capitulated before reaching the border, von Lettow-Vorbeck and his column was able to reach the Rovuma River. Facing supply shortages, the German general then reduced his force by dismissing a large number of Askaris, who could not be adequately equipped, as well as a number of camp followers.[5] With his reduced force, von Lettow-Vorbeck made plans to attack the Portuguese garrison across the river at Ngomano. The Portuguese force was a native contingent led by European officers under João Teixeira Pinto, a veteran with experience fighting in Africa.[6][lower-alpha 1] Rather than prepare defensive positions, the Portuguese had begun building a large encampment upon their arrival at Ngomano on 20 November. Pinto had at his disposal 900 troops with six machine guns and a large supply cache but his inexperienced force was no match for von Lettow-Vorbeck's force, which crossed the river with between 1,500 and 2,000 veterans as well as a large number of porters.[7]

Battle

At 07:00 on the morning of 25 November, the Portuguese garrison at Ngomano received word from a British intelligence officer that an attack was about to commence. Nevertheless, when the attack came they were unprepared.[8] In order to distract Pinto and his men, the Germans shelled the camp from across the river with high explosive rounds. While the artillery attacked the camp, the Germans moved their forces upstream and crossed the Rovuma safely out of sight of Pinto and his men.[9] The Portuguese did not resist von Lettow-Vorbeck's forces when they crossed the river and remained encamped at Ngomano. The Germans were easily able to flank the Portuguese positions and completely envelop them with six companies of German infantry attacking the camp from the south, south-east and west.[10]

Having been forewarned about the attack, the Portuguese commander had been able to begin preparations for the assault; however, he had planned on receiving a frontal assault and when the force came under attack from the rear he was completely surprised. The Portuguese attempted to entrench themselves in rifle pits, but they became disoriented after Pinto and several other officers were slain early in the engagement.[11]

The Germans had very little in the way of heavy weapons, as they had discarded most of their artillery and machine guns due to lack of ammunition. Despite the chronic ammunition shortage von Lettow-Vorbeck was able to move four machine guns up close to the rifle pits, using them only at close range to ensure his ammunition would not be wasted. The inexperience of the Portuguese proved to be their downfall; despite their firing over 30,000 rounds, German casualties were extremely light, including only one casualty among their officers. Taking heavy casualties, having lost their commanding officer, and finding themselves hopelessly outnumbered, the Portuguese finally surrendered despite the fact that they had enough military supplies to continue the action.[12][lower-alpha 2]

Aftermath

The German casualties were light, with only a few Askaris and one European killed. The Portuguese, on the other hand, had suffered a massive defeat and by failing to prevent von Lettow-Vorbeck's force from crossing the Rovuma allowed him to continue his campaign until the end of the war. Estimates of Portuguese casualties vary, with some sources providing figures of over 200 Portuguese killed and wounded and nearly 700 taken prisoner;[13] other writers state around 25 Portuguese killed along with 162 Askari, with almost 500 captured.[lower-alpha 3] The prisoners of war were used by the Germans as porters for the 250,000 rounds of ammunition, six machine guns and several hundred rifles that were also captured.[14] With this equipment, the Germans managed to completely resupply their force. Von Lettow-Vorbeck abandoned and destroyed the majority of his force's German weaponry for which he had no ammunition and armed his troops with Portuguese and British weapons. Portuguese uniforms seized from the captured prisoners were used to replace the ragged old German ones that the force had previously worn.[15]

Von Lettow-Vorbeck did not stay at Ngomano for long and soon marched his force south to attack more Portuguese positions, leaving only one company at Ngomano as a rearguard in case the British decided to follow him into Portuguese East Africa. His force won several more victories while seizing even more supplies and ammunition before moving back into German East Africa in 1918.[16]

Notes

- Paice states that the garrison commander was a Major Quaresma, who was in command by virtue of his seniority over Pinto, but who lacked any combat experience (2008, p. 340).

- Paice states that following the battle, a British intelligence officer inspected the scene of the fighting and is reported to have stated that far from having adequate supplies as indicated by the garrison commander, the Portuguese had actually been short of food and were "on the brink of starvation" (2008, p. 339).

- Von Lettow-Vorbeck is said to have estimated about 200 dead, with 150 Europeans being released on parole and several hundred Askaris being taken prisoner. Heinrich Schnee provided the lesser figures mentioned above. (Paice 2008, p. 340.)

Footnotes

- Downes 1919, p. 179.

- Chisholm 1922, p. 885.

- Chisholm 1922, p. 884.

- "Portugal is in war". The Washington Post. Washington. March 10, 1916. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- Strachan 2004, p. 175.

- Downes 1919, p. 180.

- Newitt 1995, p. 419.

- Paice 2008, p. 339.

- Dane 1919, p. 150.

- Paice 2008, p. 339.

- Downes 1919, p. 179.

- Downes 1919, p. 280.

- Dane 1919, p. 150.

- Paice 2008, p. 340.

- Dane 1919, p. 150.

- Downes 1919, p. 281.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh (1922). The Encyclopædia Britannica, The Twelfth Edition, Volume 2. New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company, Ltd. OCLC 71368873.

- Dane, Edmund (1919). British Campaigns in Africa and the Pacific, 1914–1918. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 2460289.

- Downes, Walter (1919). With the Nigerians in German East Africa. London: Methuen & Co. OCLC 10329057.

- Newitt, Malyn (1995). A History of Mozambique. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 419. ISBN 0-253-34006-3.

rovuma lettow.

- Paice, Edward (2008) [2007]. Tip & Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2349-1.

- Strachan, Hew (2004). The First World War in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925728-0.