Bila Tserkva

Bila Tserkva (Ukrainian: Бі́ла Це́рква [ˈbilɐ ˈtsɛrkwɐ]; lit. ''White Church'') is a city in the center of Ukraine, the largest city in Kyiv Oblast (after Kyiv, which is the administrative center, but not part of the oblast), and part of the Right Bank. It serves as the administrative center of Bila Tserkva Raion and hosts the administration of Bila Tserkva urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine.[1] Bila Tserkva is located on the Ros River approximately 80 km (50 mi) south of Kyiv. The city has an area of 67.8 square kilometres (26.2 sq mi).[2] Its population is approximately 207,273 (2022 estimate).[3]

Bila Tserkva

Біла Церква | |

|---|---|

View of the Church of St. John the Baptist on Castle Hill in Bila Tserkva, Ukraine. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Bila Tserkva Location of Bila Tserkva  Bila Tserkva Bila Tserkva (Ukraine) | |

| Coordinates: 49°47′56″N 30°06′55″E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Raion | |

| Founded | 1032 |

| Magdeburg Rights | 1589 |

| Government | |

| • Head of City Council | Gennadii Dykyi |

| Area | |

| • Total | 67.8 km2 (26.2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 178 m (584 ft) |

| Population (2022) | |

| • Total | 207,273 |

| • Density | 3,100/km2 (7,900/sq mi) |

| Postal code | 09100-09117 |

| Area code | (+380) 4563 |

| Vehicle registration | AI/10 |

| Sister cities | Barysaw, Jingzhou, Kaunas, Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski, Kremenchuk |

| Website | http://bc-rada.gov.ua/ |

The ancient city of Bila Tserkva was founded in 1032 to provide important defenses against nomadic tribes. In the 13th century, it was invaded by the Mongols, however, and the city was devastated.[4] In 1651, it was the site of an important battle between the warring Zaporozhian Cossack Army (and their Tatar allies) and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but Bila Tserkva was also where they made peace, and signed a Treaty.[5] In 1791, Russia's Catherine II included Bila Tserkva in the region that came to be known as the Pale of Settlement, which encompassed parts of seven contemporary nations, including large swaths of modern-day Ukraine.[6]

Architecturally, the town is known for a variety of late 18th and early 19th-century buildings, courtesy of the Branickis, who ruled there during this era. Highlights include:

The Winter Palace on the bank of the Ros River, the Summer Palace, an ensemble of postal station buildings, the Church of Saint John the Baptist (1789–1812), the Transfiguration Cathedral (1833–9), and the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene (1843). The Church of Saint Nicholas, whose construction was initiated by Hetman Ivan Mazepa and Colonel Kostiantyn Maziievsky in 1706, and was finally completed in 1852.[7]

By the late 19th century, Jews would comprise nearly half the population of the city.[8][9] An important Jewish center, it also evolved into an active center for the exchange of influential ideas about politics, religion, art, and culture, with an active Zionist movement, an active branch of the Decembrist movement and a branch of the Society of United Slavs formulating "plans to assassinate Tsar Alexander I."[7] A center of Hassidim, it also hosted vigorous factions arguing for assimilation. Home to many artists and writers, Sholem Aleichem and Shaye Shkarovsky spend periods writing there in Yiddish, and Ivan Nechuy-Levytsky was also writing in Ukrainian during this era.

An important regional center during Lithuanian and, later, Polish rule, the city remained prominent due to its close proximity to Kyiv, and its place at the center of Europe's "breadbasket," with some of the continent's most fertile land.[7][10] The city economy first began diversifying in the late 1700s when the Oleksandriia Dendrological Park was first built.[10] In 1809–14, Market Stalls were created to provide space for 85 merchants at a time when the grain trade and sugar industry also began to contribute to the growth of the city.[11] By 1850, Bila Tserkva had built its first major factory. Later, it specialized in building machines for everything from the production of feed for livestock, to tires, to clothing."[10] In 1929, the Bila Tserkva National Agrarian University was founded in as a scientific research center, which now specializes in academic research focusing on environmental protection, veterinary welfare and biosafety.[12]

During the first two decades of the 20th century, the city's Jewish residents were subject to multiple pogroms. In 1919 and 1920 alone, pogroms were responsible for the deaths of 850 Jews.[13] In 1932–1933, as many as 22,000 of greater Bila Tserkva's residents died in the Holodomor.[14]

During the Second World War, the city was occupied by Nazi Germany as part of Operation Barbarossa, resulting in the 1941 massacre of the city's Jewish population.[15] The city was recaptured by Soviet forces and returned to the control of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1944.[16] In 1991, Ukraine declared independence.

History

Founded in 1032, the city was originally named Yuriiv by Yaroslav the Wise, whose Christian name was Yuri. The contemporary name of the city, literally translated, is "White Church" and may refer to the white-painted cathedral (no longer extant) of medieval Yuriiv.[17] In its long history, Bila Tserkva spent its first few hundred years privately owned, later, though the owner was typically a citizen of the ruling empire, it was organized as a fiefdom.

From its earliest incarnation, however, Bila Tserkva was considered to provide important defense against nomadic tribes that included both the Cumans and the Tatars. Its defenses failed during a 13th-century Mongol invasion, however, and the city was devastated.[4]

Lithuanian and Polish rule

From 1363, Bila Tserkva belonged to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and from 1569 to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, administratively in the Powiat of Kyiv, part of Lesser Poland. It was crown property, but in recognition of his great service, it was granted to the Castellan of Kraków, Janusz Ostrogski. The next owner was Stanisław Lubomirski (1583–1649) and during his time the town was granted Magdeburg Rights by Sigismund III Vasa in 1620.

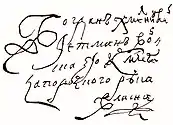

After subduing the rebellious Cossacks in the 1626 Battle of Bila Tserkva, the next owner of the estate was Prince Jerzy Dymitr Wiśniowiecki. The castle was successfully taken by Bohdan Khmelnytsky in 1648. In 1651, it was also the site of the Battle of Bila Tserkva between the warring Zaporozhian Cossack Army (and their Tatar allies) and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but Bila Tserkva was also where they made peace, and signed a Treaty.[5][18] In 1666, six-thousand Muscovite troops laid siege to Bila Tserkva. The standoff lasted until the following year when Polish reinforcements led by Jan Stachurski with the aid of allied Cossacks and Iwan Brzuchowiecki smashed Petro Doroshenko's stranglehold.

The next owner was Great Crown Hetman Stanislaw Jan Jabłonowski. In 1702, the castle was taken by the Cossack leader, Semen Paliy who made it his domain. In 1708, the town was overrun by prince Golitsyn's Russian army. The next owner of the town was Jan Stanislaw Jabłonowski, then Stanisław Wincenty Jabłonowski who erected a catholic church. After him ownership passed to Jerzy August Mniszech. The town was substantially refortified.

In 1774, Bila Tserkva (Biała Cerkiew), then the seat of the sub-prefecture (Starostwo), came into the possession of Stanisław August Poniatowski who that same year granted the property to Franciszek Ksawery Branicki, Poland's Grand Hetman who then built his urban residence, the Winter Palace complex and a country residence with the "Oleksandriia" Arboretum (named after his wife Aleksandra Branicka). He founded the Catholic Church of John the Baptist, and started construction of the Orthodox church, which was completed by his successor, his son Count Władysław Grzegorz Branicki. The latter also built the gymnasium-school complex in Bila Tserkva. Aleksander Branicki, the youngest grandson of the hetman, renovated and finished Mazepa's Orthodox church. Under the rule of count Władysław Michał Branicki, Bila Tserkva developed into a regional commercial and manufacturing centre.[19][20]

The Russian Empire

In 1791, Russia's Catherine II, included Bila Tserkva in the region that came to be known as the Pale of Settlement, which encompassed parts of seven contemporary nations, including large swaths of modern-day Ukraine.[6] Bila Tserkva was formally annexed into the Russian Empire as a result of the Second Partition of Poland in 1793.[21] Meanwhile, after 1861, the Czarist authorities converted Roman Catholic churches into Orthodox Churches.[22] By the late 18th century, however, Jews were already living in the region, and within a century they would comprise nearly half the population of the city.[8] An important Jewish city, as a result, by the early 1900s it was a fount of idea about politics, religion, art, and culture, with an active Zionist movement, an active branch of the Decembrist movement and a branch of the Society of United Slavs formulating"plans to assassinate Tsar Alexander I by Sergei Muravev-Apostol and his co-conspirators."[7] Home to many artists and writers, Sholem Aleichem and Shaye Shkarovsky were both writing in Yiddish, with Ivan Nechuy-Levytsky writing in Ukrainian. It also was the home of artists like Luka Dolinski and Halyna Nevinchana; as well as theater and film directors Eugene Deslaw and Les Kurbas..

Soviet rule and Nazi occupation

22,000 residents of the city and its environs died under the Soviet Famine-Genocide of 1932–3.[14]

During World War II, Bila Tserkva was occupied by the German Army from 16 July 1941 to 4 January 1944.[23] In August 1941 Bila Tserkva was the site the Nazi massacre, now known as the Bila Tserkva massacre of the city's Jewish population, which required the separate executions of nearly 100 children.[15][24] A Monument to Jewish Children and the Holocaust was unveiled in Bila Tserkva in 2019.[25]

Independent Ukraine

Until 18 July 2020, Bila Tserkva was incorporated as a city of oblast significance and served as the administrative center of Bila Tserkva Raion even though it did not belong to the raion. In July 2020, as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Kyiv Oblast to seven, the city of Bila Tserkva was merged into Bila Tserkva Raion.[26][27]

During the Battle of Vasylkiv, a Russian Il-76, carrying over 100 paratroopers, was allegedly shot down over Bila Tserkva.[28][29][30]

Jewish history

In Jewish folklore the city came to be referred to as the "Black Contamination" (Yid. Shvartse Tume), a play on its name in Russian ("White Church").[31] The earliest Jewish inhabitants have been traced to 1648.[32][13] The population, however, has risen and fallen due to outbreaks of violence and, later, pogroms.[31] By the end of the 19th century, Jews made up a slight majority of the population at 52.9% of the city's total population, or 18,720 total inhabitants.[8] According to the Jewish Virtual Library, in 1904, Jews owned 250 workshops and 25 factories engaged in light industry employing 300 Jewish workers."[31] Cossack-led attacks, Stalin's purges, pogroms and the Holocaust, including the horrors of the Bila Tserkva massacre, caused a major demographic shift. By 2001, it was mostly inhabited by ethnic Ukrainians, with a meager Jewish population of less than 0.1%.

| 1926 | 1939 | 1959 | 1989 | 2001 | |

| Jews | 36.4% | 19.6% | 7.8% | 2.0% | 0.1% |

| Russians | 3.4% | 7.6% | 18.6% | 17.5% | 10.3% |

| Ukrainians | 57.0% | 68.9% | 71.0% | 78.6% | 87.4% |

| Belarusians | 0.3% | 1.0% | 0.8% | 0.6% | |

| Poles | 2.4% | 2.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

In the late 1980s, Kyiv's Judaica Institute began taking form"after the tragic decades of Bolshevik repressions, Nazi genocide of the Jewish people, and bans on Jewish studies" to research and "popularize the past and the present of the Jewish community of Ukraine."[33]

In 1991, Ukraine declared independence, and two years after the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, Volodymyr Groysman became Ukraine's first Jewish prime minister. Three years later, Ukraine elected Volodymyr Zelenskyy as its first Jewish president.[34] A 2017 Pew Research study found that Ukraine was the most accepting of Jews among all Central and Eastern European countries, a later research study in 2019 confirmed those results.[35][36]

Geography

Climate

Bila Tserkva is located at 49°47'58.6" North, 30°06'32.9" East and is 178 metres (584 ft) above sea level. The city has a total area of 67.8 square kilometres (26.2 sq mi).

| Climate data for Bila Tserkva (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.1 (30.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

0.1 (32.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.8 (25.2) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

1.4 (34.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.4 (20.5) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 30.8 (1.21) |

31.1 (1.22) |

30.6 (1.20) |

44.9 (1.77) |

47.6 (1.87) |

74.2 (2.92) |

76.6 (3.02) |

56.4 (2.22) |

52.2 (2.06) |

34.6 (1.36) |

41.3 (1.63) |

37.9 (1.49) |

558.2 (21.98) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.7 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 91.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.1 | 83.2 | 78.1 | 67.7 | 63.8 | 70.7 | 71.4 | 69.3 | 74.3 | 79.1 | 86.1 | 87.6 | 76.4 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[37] | |||||||||||||

Economy

The city economy first began diversifying in the late 1700s, when Alexandra Branicki, the wife of the Polish King Franciszek Ksawery Branicki had a 400-hectare landscaped park designed.[10] The Oleksandriia Dendrological Park is now a part of Ukraine's National Academy of Sciences, and it currently cultivates more than 1,800 endemic and exotic plant species, with more than 600 species of exotic trees and shrubs alone, in addition to publishing academic research.[10][11] By 1850, Bila Tserkva had built its first major factory. Later, it "began to specialize in building machines for the production of feed for livestock, electrical capacitors, tires, rubber-asbestos products, shoes, clothing, furniture, and reinforced-concrete products."[10] Industry in the city includes Railway Brake product manufacturers "Tribo Rail", Tribo plant and a major automobile tire manufacturer "Rosava".

Education

Education in Bila Tserkva is provided by many private and public institutions. Its best known is the Bila Tserkva National Agrarian University was founded in 1929 as a scientific research center publishing academic studies on modern agrobiotechnology, nature and environmental protection; the latest technologies for processing livestock products; biosafety, the veterinary welfare of livestock; regulation of bioresources and sustainable nature management; rationalization of social development of rural areas; economics of agro-industrial complex, legal sciences, linguistics and translation.[12] They partner with institutions of higher learning worldwide, and participate in programs with Erasmus+, the British Council, NATO and Fulbright, among several others.[12]

Sports

During the Cold War, the town was host to the 72nd Guards Krasnograd Motor Rifle Division[38] and the 251st Instructor Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment of Long Range Aviation.[39] The city is also home to football team FC Ros Bila Tserkva. Ros is a team in the lower levels of the Football Federation of Ukraine: Kyiv Oblast Football Championship. The city is also home to hockey club Bilyi Bars, that plays on Bilyi Bars Ice Arena, built by Kostyantyn Efymenko Charitable Foundation.

Landmarks

- A historical landscape park Arboretum Oleksandriya of 400 acres is situated in Bila Tserkva. It was founded in 1793 by the wife of Polish Hetman Franciszek Ksawery Branicki.

- Notable buildings include the Merchant Court (1809–1814) and the Post Yard (1825–31).

- There are also Palladian wooden buildings of the Branicki "Winter Palace" and, once, the District Nobility Assembly, prior to a fire.

- St. Nicholas Church was started in 1706 by Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa, but not completed until 1852.

- The Orthodox Saviour's Transfiguration Cathedral was constructed in 1833–1839.

- The Roman Catholic St. John the Baptist Church dates to 1812.

- The St. Mary Magdalene Church was completed in 1846 by Count Branicki.

- The building of the mid-19th century Great Choral Synagogue is preserved. Today it is the Technology and Economic College of Bila Tserkva National Agrarian University.

- The Shukhov Water Tower, a tower that supports a water tank was built according to a project of Vladimir Shukhov, a Russian engineer-polymath, scientist and architect.

Churches

St. George the Victorious was recently rebuilt from ruins in the manner of an ancient 11–12th c. Ruthenian temple, on the foundation of the church destroyed by the Tatar-Mongols. It is said to be the white church that gave the city its name in a 14th c. homage to Yaroslav the Wise.[40]

St. George the Victorious was recently rebuilt from ruins in the manner of an ancient 11–12th c. Ruthenian temple, on the foundation of the church destroyed by the Tatar-Mongols. It is said to be the white church that gave the city its name in a 14th c. homage to Yaroslav the Wise.[40] 1706–1852 | St. Nicholas was started in 1706 by Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa, but not completed until 1852.

1706–1852 | St. Nicholas was started in 1706 by Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa, but not completed until 1852. 1812 | St. John the Baptist ("the Organ and Chamber Music Hall") was built in 1812.

1812 | St. John the Baptist ("the Organ and Chamber Music Hall") was built in 1812..jpg.webp) 1833–1839 | Orthodox Savior's Transfiguration Cathedral

1833–1839 | Orthodox Savior's Transfiguration Cathedral 1830s | Interior entrance of the Savior's Transfiguration Cathedral

1830s | Interior entrance of the Savior's Transfiguration Cathedral 1901 | Heather Church

1901 | Heather Church

Synagogues

1854–1860 | The Great Choral Synagogue, ca. 1895 and 1910 when it was actively used.

1854–1860 | The Great Choral Synagogue, ca. 1895 and 1910 when it was actively used. 1854 to 1860 | The mid-19th century Great Choral Synagogue is now used as the Technology and Economic College of the National Agrarian University.

1854 to 1860 | The mid-19th century Great Choral Synagogue is now used as the Technology and Economic College of the National Agrarian University.

City sites

The arcades of the Merchant Court, interior, built in 1809–1814

The arcades of the Merchant Court, interior, built in 1809–1814 The main entrance to the recently revived Merchant Court, built in 1809–1814

The main entrance to the recently revived Merchant Court, built in 1809–1814.JPG.webp) Square No. 6 is one of many alternate shopping centers.

Square No. 6 is one of many alternate shopping centers. Entrance to the Labor Reserves Stadium

Entrance to the Labor Reserves Stadium View from the Ros River to Castle Hill and the Church of St. John the Baptist

View from the Ros River to Castle Hill and the Church of St. John the Baptist 1793 statue adorning the 400-acre Oleksandriia Park

1793 statue adorning the 400-acre Oleksandriia Park Branicki's Winter Palace was built in the Palladian style c. 1796.

Branicki's Winter Palace was built in the Palladian style c. 1796. The entrance to Arboretum Oleksandriia

The entrance to Arboretum Oleksandriia

Transportation

Airports

Domestic transport and private flights provide services via Bila Tserkva Airport (UKBC), which is located southwest of the city in Hayok district.

Bila Tserkva Air Base is located nearby.

Rail

Ukrzaliznytsia provides railway transit to surrounding areas in Kyiv Oblast and the rest of Ukraine.

There are two railway stations in Bila Tserkva:

- Bila Tserkva railway station

- Rotok railway station

Public transit

Bila Tserkva has six trolleybus lines.

Bridges

Bila Tserkva is the location of a few large bridges, two of which cross the Ros River.

Notable people

- Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916) – leading Yiddish author and playwright. The Fiddler on the Roof musical is based on his stories.[41]

- David Bronstein (1924–2006) – leading chess grandmaster and writer

- Mother Elżbieta Róża Czacka (1876–1961) – philanthropist and nun, born in Bila Tserkva, and beatified in 2021

- Eugene Deslaw (1898–1966) – avant-garde French cinema director, also known for introducing the Boy Scouts to Ukraine

- Luka Dolinski (1750–1830) – painter, representative of the late Ukrainian Baroque, Rococo and Classicism, educated at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

- Volodymyr Dyudya (born 1983) – professional Ukrainian cyclist

- Kostyantyn Efymenko (born 1975) – president of Biofarma, Chairman of Tribo

- Mikhail Eisenstein (1867-1920, born as Moisey Eisenstein) - civil engineer, designer many of the best-known Art Nouveau buildings of Riga, Latvia, and the father of Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein

- David Goodman, father of Benny Goodman – American jazz and swing musician, clarinetist and bandleader; widely known as the "King of Swing"

- Axel Firsoff (1910–1981) – British astronomer, born in Bila Tserkva

- Boris Samoilovich Iampol'skii (1912–1972) – Russian-language writer

- Andrzej Klimowicz (1918–1996) – operative for Zegota, the government-supported resistance group, organized to help Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. They are said to have saved tens of thousands from 1942 to 1945.

- Les Kurbas (1887–1937) – movie and theater director, co-founder of Soviet theater avant-garde and a prominent figure of the Executed Renaissance

- Yuri Linnik (1915–1972) – Soviet mathematician

- Ivan Mazepa (1639–1709) – Hetman of Zaporizhian Host from 1687 to 1708[42]

- Olexandr Medvid' (born 1937) – Soviet Belarusian wrestler

- Halyna Nevinchana (born 1957) – painter, writer, journalist

- Ivan Nechuy-Levytsky (1838–1918) – writer, ethnographer, folklorist, teacher

- Lyudmila Pavlichenko (1916–1974) – World War II Soviet sniper. Credited with 309 kills, she is regarded as one of the top military snipers of all time and the most successful female sniper in history.

- Pavlo Popovich (1930–2009) – Soviet astronaut, fourth ever person in outer space, twice Hero of the Soviet Union

- Yossele Rosenblatt (1882–1933) – American cantor

- Shaye Shkarovsky (1891–1945) – Yiddish author

- Yaakov Steinberg (1887–1947) – Yiddish and Hebrew short-story writer, essayist, critic, and translator[43]

- Mikhael Sukernik (1902–1981) – Soviet Russian-Ukrainian chemist who contributed to the development and publication of a Russian-Yiddish dictionary published in 1984

Sister cities

See also

References

- "Белоцерковская городская громада" (in Russian). Портал об'єднаних громад України.

- General information about the city Archived 17 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, at Bila Tserkva official web-site Archived 20 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2022 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2022] (PDF) (in Ukrainian and English). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2022.

- Kohut, Zenon E. "Mazepa's Ukraine: Understanding Cossack Territorial Vistas." Harvard Ukrainian Studies 31, no. 1/4 (2009): 1–28. .

- PERNAL, A. B. "The Expenditures of the Crown Treasury for the Financing of Diplomacy between Poland and the Ukraine during the Reign of Jan Kazimierz." Harvard Ukrainian Studies 5, no. 1 (1981): 102–20. .

- "The Pale of Settlement". Facing History and Ourselves. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- "Belaya Tserkov | Encyclopedia.com". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Архівована копія.

- "Belaya Tserkov". Ukraine Jewish Heritage: History of Jewish communities in Ukraine. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- "Bila Tserkva". encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- "Belaya Tserkov". Ukraine Jewish Heritage: History of Jewish Communities in Ukraine. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- "Bila Tserkva National Agrarian University". About University: Bila Tserkva National Agrarian University. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016.

- "Российская Еврейская Энциклопедия". rujen.ru. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- Boryssenko, Valentyna, Lisa Vapné, and Anne Coldefy-Faucart. "La Famine En Ukraine (1932-1933)." Ethnologie Française 34, no. 2 (2004): 281–89. .

- Martin Dean (2018). Antisemitism Studies. 2 (2): 365. doi:10.2979/antistud.2.2.10 https://doi.org/10.2979/antistud.2.2.10.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Ukraine's history and its centuries-long road to independence". PBS NewsHour. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "Bila Tserkva". encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A history of Ukraine, University of Toronto Press, 1996, p. 205

- E. A. Chernecki, L. P. Mordatenko, Bila Tserkva. Branicki family. Alexandria, Ogrody rezydencji magnackich XVIII-XIX wieku w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej oraz problemy ich ochrony, Ośrodek Ochrony Zabytkowego Krajobrazu—Narodowa Instytucja Kultury, 2001, p. 114

- Marek Ruszczyc, Dzieje rodu i fortuny Branickich, Delikon, 1991, p. 148

- "Ukraine's fraught relationship with Russia: A brief history". The Week. 8 March 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Lucjan Blit, The origins of Polish socialism: the history and ideas of the first Polish Socialist Party 1878–1886, Cambridge University Press, 1971, p. 21

- "Onwar.com, Allies support resistance in Europe". Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- "The Untold Stories: The Murder of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR". yadvashem.org. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- "Monument Jewish Children and the Holocaust Bila Tserkva – Bila Tserkva – TracesOfWar.com". tracesofwar.com. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in Ukrainian). 18 July 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України.

- The Kyiv Independent [@KyivIndependent] (25 February 2022). "⚡️Second Russian Il-76 transporter downed. Ukraine's air defense near Bila Tserkva killed the second aircraft that could carry over 100 paratroopers for landing to the south of Kyiv. Source: Ukraine's State Agency for Special Communications" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022 – via Twitter.

- "US officials say 2 Russian transport planes shot down over Ukraine". Times of Israel. AP. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- "Sorting fact, disinformation after Russian attack on Ukraine". ABC News. Associated press. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- "Belia Tserkov". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- Stampfer, Shaul. "What Actually Happened to the Jews of Ukraine in 1648?" Jewish History 17, no. 2 (2003): 207–27. .

- "About the Center". 4 April 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- "Ukraine's turbulent history since independence in 1991". Reuters. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- Wike, Richard; Poushter, Jacob; Silver, Laura; Devlin, Kat; Fetterolf, Janell; Alex; Castillo, ra; Huang, Christine (14 October 2019). "6. Minority groups". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- "For many Jews, Ukraine brings up memories of pogroms, antisemitism and Nazi collaboration. But Jewish life in Ukraine is no longer what it was". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Carey Schofield, Inside the Soviet Army, Headline Book Publishing, 2001, 132.

- Michael Holm, 251st Instructor Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment, accessed December 2012.

- "Центральный вход в церковь.Св.Георгия Победоносца. – Picture of Church of St. George, Bila Tserkva – Tripadvisor". tripadvisor.com. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- – via Wikisource.

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). p. 942.

- "YIVO | Steinberg, Ya'akov". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- "Miasta Partnerskie". Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- "Vereinbarung für Solidaritätspartnerschaft mit Bila Tserkva unterzeichnet". Retrieved 18 December 2022.