Bight of Biafra

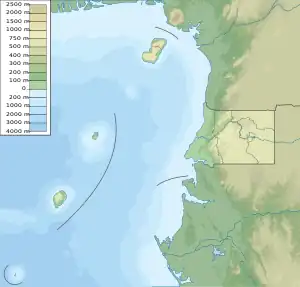

The Bight of Biafra (known as the Bight of Bonny in Nigeria) is a bight off the west-central African coast, in the easternmost part of the Gulf of Guinea.

| Bight of Biafra | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Gulf of Guinea map showing the Bight of Biafra. | |

Bight of Biafra | |

| Coordinates | 2°50′N 8°0′E |

| Native name | Golfo de Biafra (Portuguese) |

| River sources | Niger |

| Ocean/sea sources | Gulf of Guinea Atlantic Ocean |

| Basin countries | Nigeria, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon |

| Max. length | 300 km (190 mi) |

| Max. width | 600 km (370 mi) |

| Islands | Bioko |

Geography

The Bight of Biafra, or Mafra (named after the town Mafra in southern Portugal), between Cape Formosa and Cape Lopez, is the most eastern part of the Gulf of Guinea; it contains the islands Bioko [Equatorial Guinea], São Tomé and Príncipe. The name Biafra – as indicating the country – fell into disuse in the later part of the 19th century [1]

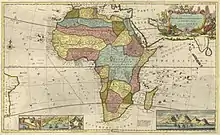

A 1710 map indicates that the region known as "Biafra" (Biafra) was located in present-day Cameroon.

The Bight of Biafra extends east from the River Delta of the Niger in the north until it reaches Cape Lopez in Gabon.[2] Besides the Niger River, other rivers reaching the bay are the Cross River, Calabar River, Ndian, Wouri, Sanaga, Nyong River, Ntem, Mbia, Mbini, Muni and Komo River.

The main islands in the Bay are Bioko and Príncipe; other important islands are Ilhéu Bom Bom, Ilhéu Caroço, Elobey Grande and Elobey Chico. Countries located at the Bight of Biafra are Cameroon, the eastern region of Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea (Bioko Island and Rio Muni), and Gabon[3]

History

The Bight of Biafra accounted for an estimated 10.7% of all enslaved people that were transported to the Americas between 1519-1700. Between 1701-1800, it accounted for an estimated 14.97%.[4] Those stolen from the Bight of Biafra include the Bamileke, Igbo, Tikar, Bakossi, Fang, Massa, Bubi and many more.[2][4] These captured Africans arrived in what would become the United States and were sold in Virginia, which held 60% of all slaves on the eastern coast. Virginia and surrounding colonies held 30,000 slaves.[5] Normally, enslaved people were cheaper when bought in Cameroon because they preferred to die rather than accept slavery.[6]

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Bonny had emerged as the major slave trading port on the Bight of Biafra outpacing the earlier dominant slave ports at Elem Kalabari (also known then as New Calabar) and Old Calabar. These 3 ports together accounted for over 90% of the slave trade emanating from the Bight of Biafra.[7][8]

Timeline

Between 1525 and 1859, the British accounted for over two-thirds of slaves exported from the Bight of Biafra to the New World.[9]

In 1777, Portugal transferred control of Fernando Po and Annobón to Spanish suzerainty thus introducing Spain into the early colonial history of the Bight of Biafra.[10]

In 1807, the United Kingdom made illegal the international trade in slaves, and the Royal Navy was deployed to forcibly prevent slavers from the United States, France, Spain, Portugal, Holland, West Africa and Arabia from plying their trade.[11]

On 30 June 1849, Britain established its military influence over the Bight of Biafra by building a naval base and consulate on the island of Fernando Po,[12] under the authority of the British Consuls of the Bight of Benin:[13]

On 30 June 1849, Britain established its military influence over the Bight of Biafra by building a naval base and consulate on the island of Fernando Po,[12] under the authority of the British Consuls of the Bight of Benin:[13]

On 6 August 1861, the Bight of Biafra and the neighboring Bight of Benin (under its own British consuls) became a united British consulate, again under British consuls:

- May 1852-1853…Louis Fraser

- 1853-April 1859…Benjamin Campbell

- April 1859-1860…George Brand

- 1860-January 1861…Henry Hand

- January-May 1861…Henry Grant Foote

- May-6 August 1861…William McCoskry (acting)

- 1861-December 1864…Richard Francis Burton

- December 1864-1873…Charles Livingstone

- 1873-1878…George Hartley

- 1878-13 September 1879…David Hopkins

- 13 September 1879-5 June 1885…Edward Hyde Hewett.

In 1967, the Eastern Region of Nigeria seceded from the Nigerian State and adopted the name of its coastline, the adjoining Bight of Biafra, becoming the newly independent Republic of Biafra. This independence was short-lived as the new state lost the ensuing Nigerian Civil War. In 1975, by decree, the Nigerian government changed the name of the Bight of Biafra to the Bight of Bonny.[14]

Pulsations

In 1962, Jack Oliver, a geologist at Columbia University, first noticed the earth had a "pulse" also known in geology lingo as a "microseism". This discovery was put on the shelves and re-examined briefly in 1980 by Gary Holcomb and then fully examined in 2005 by graduate student Greg Benson at the University of Colorado.[15]

Later results revealed that the earth pulses every 26 seconds, but nobody is exactly sure why. Theories range from waves hitting the continental shelf to volcanic activity.

By using triangulation, they were able to locate the source of the pulse in the Bight of Bonny.[16]

References

- Hugh Chisholm; James Louis Garvin (1926). The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature & general information, Volumes 11-12. The Encyclopædia Britannica Company, ltd., 1926. p. 696. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Biafra, Bight of." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- "Biafra, Bight of | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- "NPS Ethnography: African American Heritage & Ethnography". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- Frey, Sylvia R. (1983). "Between Slavery and Freedom: Virginia Blacks in the American Revolution". The Journal of Southern History. 49 (3): 375–398. doi:10.2307/2208101. ISSN 0022-4642.

- Nwokeji, G. Ugo; Eltis, David (2002). "Characteristics of Captives Leaving the Cameroons for the Americas, 1822-37". The Journal of African History. 43 (2): 191–210. ISSN 0021-8537.

- Paul E. Lovejoy (10 October 2011). Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. Cambridge University Press, 2011. p. 58. ISBN 9781139502771. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- Toyin Falola; Raphael Chijioke Njoku (26 September 2016). Igbo in the Atlantic World: African Origins and Diasporic Destinations. Indiana University Press, 2016. p. 83. ISBN 9780253022578. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- Toyin Falola; Raphael Chijioke Njoku (26 September 2016). Igbo in the Atlantic World: African Origins and Diasporic Destinations. Indiana University Press, 2016. p. 83. ISBN 9780253022578. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- I. K. Sundiata (1996). From Slaving to Neoslavery: The Bight of Biafra and Fernando Po in the Era of Abolition, 1827-1930. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1996. p. 19. ISBN 9780299145101. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "African Slave Owners". BBC. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Stewart, John (1996). The British Empire: An Encyclopedia of the Crown's Holdings, 1493 Through 1995. McFarland & Company, 1996. p. 250. ISBN 9780786401772.

- "Southern Nigeria Administrators".

- University of Ibadan. Dept. of Sociology (1980). Nigerian Behavioral Sciences Journal, Volume 3, Issues 1-2. Department of Sociology, University of Ibadan, 1980. p. 11. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "The Earth Is Pulsating Every 26 Seconds, and Seismologists Don't Agree Why". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- "Earth Keeps Pulsating Every 26 Seconds. No One Knows Why". finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2021-02-23.