Bill Dickey

William Malcolm Dickey (June 6, 1907 – November 12, 1993) was an American professional baseball catcher and manager. He played in Major League Baseball with the New York Yankees for 19 seasons. Dickey managed the Yankees as a player-manager in 1946 in his last season as a player.

| Bill Dickey | |

|---|---|

Dickey with the New York Yankees in 1937 | |

| Catcher / Manager | |

| Born: June 6, 1907 Bastrop, Louisiana, U.S. | |

| Died: November 12, 1993 (aged 86) Little Rock, Arkansas, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| August 15, 1928, for the New York Yankees | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 8, 1946, for the New York Yankees | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .313 |

| Home runs | 202 |

| Runs batted in | 1,209 |

| Managerial record | 57–48 |

| Winning % | .543 |

| Teams | |

| As player

As manager | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1954 |

| Vote | 80.16% (seventh ballot) |

Dickey played with the Yankees from 1928 through 1943. After serving in the United States Navy during World War II, Dickey returned to the Yankees in 1946 as a player and manager. He retired after the 1946 season, but returned in 1949 as a coach, where he taught Yogi Berra the finer points of catching.

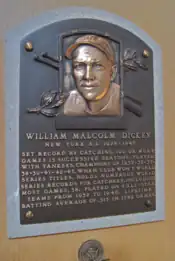

During Dickey's playing career, the Yankees went to the World Series nine times, winning eight championships. He was named to 11 All-Star Games. He went on to briefly manage the Yankees as a player-manager, then contribute to another six Yankee World Series titles as a coach. Dickey was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1954.

Early life

Dickey was born in Bastrop, Louisiana, on June 6, 1907.[1] He was one of seven children born to John and Laura Dickey. The Dickeys moved to Kensett, Arkansas, where John Dickey worked as a brakeman for Missouri Pacific Railroad. John Dickey had played baseball for a semi-professional team based in Memphis, Tennessee. Bill's older brother, Gus, was a second baseman and pitcher in the East Arkansas Semipro League, while his younger brother, George, would go on to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a catcher.[2]

Dickey attended Searcy High School in Searcy, Arkansas. At Searcy, Dickey played for the school's baseball team as a pitcher and second baseman.[2] He enrolled at Little Rock College, where he played guard for the school's American football team and pitcher for the baseball team.[2] Dickey substituted for a friend on a semi-professional team based in Hot Springs, Arkansas as a catcher, impressing the team's manager with his throwing arm.[2] Lena Blackburne, manager of the Little Rock Travelers, a minor league baseball team, noticed Dickey while scouting an outfielder on the Hot Springs team. Blackburne signed Dickey to play for his team.[2]

Minor league career

Dickey made his professional debut at the age of 18 with the Little Rock Travelers of the Class A Southern Association in 1925. Little Rock had a working agreement with the Chicago White Sox of the American League, which involved sending players between Little Rock, the Muskogee Athletics of the Class C Western Association, and the Jackson Senators of the Class D Cotton States League. Dickey played in three games for Little Rock in 1925, then was assigned to Muskogee in 1926, where he had a .283 batting average in 61 games.[2]

Dickey returned to Little Rock, and batted .391 in 17 games at the end of the season. Dickey played in 101 games for Jackson in 1927, batting .297 with three home runs. As a fielder, Dickey compiled a .989 fielding percentage and was credited with 84 assists while he committed only nine errors.[2]

New York Yankees

Jackson waived Dickey after the 1927 season. Johnny Nee, a scout for the New York Yankees, wired his boss, Ed Barrow, the Yankees' general manager, that the Yankees should claim him.[3] The Yankees purchased Dickey from Jackson for $12,500 ($213,033 in current dollar terms). Though he suffered from influenza during spring training in 1928, Dickey impressed Yankees manager Miller Huggins.[4] Dickey hit .300 in 60 games for Little Rock, receiving a promotion to the Buffalo Bisons of the Class AA International League.[2] After appearing in three games for Buffalo, Dickey made his MLB debut with the Yankees on August 15, 1928.[2] He recorded his first hit, a triple off George Blaeholder of the St. Louis Browns, on August 24.[2]

Dickey played his first full season in MLB in 1929. He replaced Benny Bengough as the Yankees' starting catcher, as Bengough experienced a recurrent shoulder injury,[5] and Dickey outperformed Bengough and Johnny Grabowski.[6] As a rookie, Dickey hit .324 with 10 home runs and 65 runs batted in (RBI).[2] He led all catchers with 95 assists and 13 double plays. In 1930, Dickey hit .339. In 1931, Dickey made only three errors and batted .327 with 78 RBI. That year, he was named by The Sporting News to its All-Star Team.[2]

Although his offensive production was overshadowed by Yankee greats Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio,[7] Dickey posted some of the finest offensive seasons ever by a catcher during the late 1930s, hitting over 20 home runs with 100 RBI in four consecutive seasons from 1936 through 1939.[1] His 1936 batting average of .362 was the highest single-season average ever recorded by a catcher, tied by Mike Piazza of the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1997, until Joe Mauer of the Minnesota Twins hit .365 in 2009.[8]

In 1932, Dickey broke the jaw of Carl Reynolds with one punch in a game after they collided at home plate, and received a 30-day suspension and $1,000 fine as punishment.[9] That year, he hit .310, with 15 home runs and 84 RBI. In the 1932 World Series, he batted 7-for-16, with three walks, 4 RBI, and scored two runs.[2]

In 1936, Dickey hit .362, finishing third in the AL behind Luke Appling (.388) and Earl Averill (.378).[2] Dickey held out for an increase from his $14,500 salary in 1936, seeking a $25,000 salary. He ended the holdout by agreeing to a contract worth $17,500.[10] Dickey earned $18,000 in 1939.[11] Dickey signed a contract for 1940, receiving a $20,500 salary.[11]

The 1941 season marked Dickey's thirteenth year in which he caught at least 100 games, an MLB record. He also set a double play record and led AL catchers with a .994 fielding percentage.[12]

Dickey suffered a shoulder injury in 1942, ending his streak of catching at least 100 games in a season. When Dickey's backup, Buddy Rosar, left the team without permission to take examinations to join the Buffalo police force and to be with his wife who was about to have a baby, Yankees manager Joe McCarthy signed Rollie Hemsley to be the second string catcher, relegating Rosar to the third string position.[13][14] Dickey saw his playing time decrease with the addition of Hemsley.[2] He returned for the 1942 World Series, but was considered to be fading.[15]

Dickey had a terrific season in 1943, batting .351 in 85 games and hitting the title-clinching home run in the 1943 World Series.[16] After the season, the 36 year-old Dickey was honored as the player of the year by the New York chapter of the Baseball Writers' Association of America.[17]

Manager and coach

Dickey was rumored to be a candidate for the managerial position with the Philadelphia Phillies after the 1943 season.[18]

Dickey entered the United States Navy on March 15, 1944, as he was categorized in Class 1-A, meaning fit for service, by the Selective Service System.[19] He served at the Navy Hospital Area in Hawaii. He was discharged in January 1946 as a lieutenant senior grade;[20] one of his main tasks had been to organize recreational activities in the Pacific.

Returning to the Yankees in 1946, Dickey became the player-manager of the Yankees in the middle of the 1946 season after Joe McCarthy resigned. The Yankees did fairly well under Dickey's watch, going 57–48. However, owner Larry MacPhail refused to give Dickey a new contract until after the season. Rather than face the possibility of being a lame-duck manager, the 39 year-old Dickey resigned on September 12, but remained as a player.[21] He retired after the season,[22] having compiled 202 home runs, 1,209 RBIs and a .313 batting average over his career.

In 1947, Dickey managed the Travelers. The team finished with a 51–103 record, last in the Southern Association.[2] Dickey returned to the Yankees in 1949 as first base coach and catching instructor to aid Yogi Berra in playing the position.[1][23] Already a good hitter, Berra became an excellent defensive catcher. With Berra having inherited his uniform number 8, Dickey wore number 33 until the 1960 season. Dickey later instructed Elston Howard on catching, when Berra moved to the outfield.[2]

Film career

While still an active player in 1942, Dickey appeared as himself in the film The Pride of the Yankees, which starred Gary Cooper as the Yankee captain and first baseman Lou Gehrig. Late in the movie, when Gehrig was fading due to the disease that would eventually take his life, a younger Yankee grumbled in the locker room, "the old man on first needs crutches to get around!"—and Dickey, following the script, belted the younger player, after which he said the kid "talked out of turn."

Dickey also appeared as himself in the film The Stratton Story in 1949. In the film, Dickey was scripted to take a called third strike from Jimmy Stewart's character. Dickey objected, stating "I never took a third strike. I always swung", and asking the director, Sam Wood, to allow him to swing through the third strike; Wood insisted that Dickey take the third strike. After many takes, Dickey commented: "I've struck out more times this morning than I did throughout my entire baseball career."[24]

Personal life

On October 5, 1932, Dickey married Violet Arnold, a New York showgirl, at St. Mark's Church in Jackson Heights, New York. The couple had one child, Lorraine, born in 1935.[2]

At the time of Lou Gehrig's death, Dickey described Gehrig as his best friend.[25]

Dickey was an excellent quail hunter.[1] He spent part of his retirement in the 1970s and 1980s residing in the Yarborough Landing community on the shore of Millwood Lake in southwestern Arkansas. He died in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1993.

Legacy

Dickey was noted for his excellent hitting and his ability to handle pitchers.[1] He was also known for his relentlessly competitive nature.

Dickey was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1954.[26] In 1972, the Yankees retired the number 8 in honor of Dickey and Berra.[2] On August 22, 1988, the Yankees honored both Dickey and Berra by hanging plaques honoring them in Monument Park at Yankee Stadium.[2] Dickey opined that Berra was "An elementary Yankee" who is "considered the greatest catcher of all time."

Dickey was named in 1999 to The Sporting News list of Baseball's Greatest Players, ranking number 57, trailing Johnny Bench (16), Josh Gibson (18), Yogi Berra (40), and Roy Campanella (50) among catchers.[27] Like those catchers, Dickey was a nominee for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, but the fan balloting chose Berra and Bench as the two catchers on the team.

In 2007, Dickey-Stephens Park opened in North Little Rock, Arkansas. The ballpark was named after Bill; his brother George; and two famous Arkansas businessmen, Jackson and Witt Stephens.

In 2013, the Bob Feller Act of Valor Award honored Dickey as one of 37 Baseball Hall of Fame members for his service in the United States Navy during World War II.[28]

See also

References

- The Miami News Archived March 8, 2020, at the Wayback Machine via Google News Archive Search

- "Bill Dickey". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- Broeg, Bob (June 13, 1970), "Bill Dickey...A Yankee of Distinction", The Sporting News 169: 18

- "Huggins Selects The Pirates To Capture Pennant". St. Petersburg Times. March 24, 1928. pp. 2–1. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- "Yankees May Get Another Catcher". The Rochester Evening Journal. Associated Press. March 12, 1929. p. 1. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- "Dickey May Win Regular Post Behind Bat With Yanks This Season". The Evening Independent. NEA. May 23, 1929. p. 11. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- St. Petersburg Times via Google News Archive Search

- Minnesota Twins: Joe Mauer takes Mike Piazza's comments in stride – TwinCities.com

- St. Petersburg Times via Google News Archive Search

- The Pittsburgh Press via Google News Archive Search

- The Milwaukee Sentinel via Google News Archive Search

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette via Google News Archive Search

- "Buddy Gets Protection". Time. August 3, 1942. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- "Hemsley Picked For Job Buddy Rosar Gives Up". The Milwaukee Journal. United Press. July 20, 1942. p. 6. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- Prescott Evening Courier via Google News Archive Search

- The Free Lance-Star via Google News Archive Search

- The Milwaukee Journal via Google News Archive Search

- The Evening Independent via Google News Archive Search

- St. Petersburg Times via Google News Archive Search

- Rogers, Thomas (November 13, 1993). "Bill Dickey, the Yankee Catcher And Hall of Famer, Dies at 86". New York Times. p. 30. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- Google Books result: The Yankee Encyclopedia, p. 283

- Edmonton Journal Edmonton Bulletin via Google News Archive Search

- "Bill Dickey Signs as Yankees Coach". Ellensburg Daily Record. October 28, 1948. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- The Miami News via Google News Archive Search

- "'Best Friend'-McCarthy". Daily News. June 3, 1941. p. 44. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- The Milwaukee Journal via Google News Archive Search

- 100 Greatest Baseball Players by The Sporting News : A Legendary List by Baseball Almanac

- https://actofvaloraward.org/hof-players/ Archived October 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Bill Dickey at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Bill Dickey managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Bill Dickey at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Bill Dickey at The Deadball Era

- Bill Dickey at Find a Grave

- Bill Dickey Oral History Interview - National Baseball Hall of Fame Digital Collection