Black Monday (1987)

Black Monday (also known as Black Tuesday in some parts of the world due to timezone differences) was the global, severe and largely unexpected[1] stock market crash on Monday, October 19, 1987. Worldwide losses were estimated at US$1.71 trillion.[2] The severity of the crash sparked fears of extended economic instability[3] or even a reprise of the Great Depression.[4]

DJIA (June 19, 1987, to January 19, 1988) | |

| Date | October 19, 1987 |

|---|---|

| Type | Stock market crash |

| Outcome |

|

Possible explanations for the initial fall in stock prices include a nervous fear that stocks were significantly overvalued and were certain to undergo a correction, persistent US trade and budget deficits, and rising interest rates. Another explanation for Black Monday comes from the decline of the dollar, followed by a lack of faith in governmental attempts to stop that decline. In February 1987 leading industrial countries had signed the Louvre Accord, hoping that monetary policy coordination would stabilize international money markets, but doubts about the viability of the accord created a crisis of confidence. The fall may have been accelerated by portfolio insurance hedging (using computer-based models to buy or sell index futures in various stock market conditions) or a self-reinforcing contagion of fear.

The degree to which the stock market crashes spread to the wider (or "real") economy was directly related to the monetary policy each nation pursued in response. The central banks of the United States, West Germany and Japan provided market liquidity to prevent debt defaults among financial institutions, and the impact on the real economy was relatively limited and short-lived. However, refusal to loosen monetary policy by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand had sharply negative and relatively long-term consequences for both its financial markets and real economy.[5]

United States

Background

During a strong five-year bull market,[6][upper-alpha 1] the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) rose from 776 in August 1982 to a peak of 2,722 in August 1987.[8] The same bullish trend propelled market indices around the world over this period, as the nineteen largest enjoyed an average rise of 296 percent.[9]

On the morning of Wednesday, October 14, 1987, the United States House Committee on Ways and Means introduced a bill to reduce the tax benefits associated with financing mergers and leveraged buyouts. Unexpectedly high trade deficit figures announced on October 14 by the United States Department of Commerce had a further negative impact on the value of the US dollar while pushing interest rates upward and stock prices downward.[10] As the day continued, the DJIA dropped 95.46 points (3.81 percent) to 2,412.70, and it fell another 57.61 points (2.39 percent) the next day, down over 12 percent from the August 25 all-time high. On Friday, October 16, the DJIA fell 108.35 points (4.6 percent).[11] The drop on the 14th was the earliest significant decline among all countries that would later be affected by Black Monday.[12]

Though the markets were closed for the weekend, significant selling pressure still existed. The computer models of portfolio insurers continued to dictate very large sales.[13] Moreover, some large mutual fund groups had procedures that enabled customers to easily redeem their shares during the weekend at the same prices that existed at the close of market on Friday.[14] The amount of these redemption requests was far greater than the firms' cash reserves, requiring them to make large sales of shares as soon as the market opened on the following Monday. Finally, some traders anticipated these pressures and tried to get ahead of the market by selling early and aggressively on Monday, before the anticipated price drop.[13]

The Crash

Before the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) opened on October 19, 1987, there was pent-up pressure to sell. When the market opened, a large imbalance arose between the volume of sell and buy orders, placing downward pressure on prices. Regulations at the time allowed designated market makers (or "specialists") to delay or suspend trading in a stock if the order imbalance exceeded the specialist's ability to fulfill in an orderly manner.[15] The imbalance on October 19 was so large that 95 stocks on the S&P 500 Index (S&P) opened late, as also did 11 of the 30 DJIA stocks.[16] Importantly, however, the futures market opened on time across the board, with heavy selling.[16]

On that Monday, the DJIA fell 508 points (22.6 percent), accompanied by crashes in the futures exchanges and options markets;[17] the largest one-day percentage drop in the history of the DJIA.[18] Significant selling created steep price declines throughout the day, particularly during the last 90 minutes of trading.[19] Deluged with sell orders, many stocks on the NYSE faced trading halts and delays. Of the 2,257 NYSE-listed stocks, there were 195 trading delays and halts that day.[20] Total trading volume was so large that the computer and communications systems were overwhelmed, leaving orders unfilled for an hour or more. Large funds transfers were delayed and the Fedwire and NYSE SuperDot systems shut down for extended periods further compounding traders' confusion.[21]

Margin calls and liquidity

Frederic Mishkin suggested that the greatest economic danger was not events on the day of the crash itself, but the potential for "spreading collapse of securities firms" if an extended liquidity crisis in the securities industry began to threaten the solvency and viability of brokerage houses and specialists. This possibility first loomed on the day after the crash.[22] At least initially, there was a very real risk that these institutions could fail.[23] If that happened, spillover effects could sweep over the entire financial system, with negative consequences for the real economy as a whole.[24] As Robert R. Glauber stated, "From our perspective on the Brady Commission, Black Monday may have been frightening, but it was the capital-liquidity problem on Tuesday that was horrifying."[25]

The source of these liquidity problems was a general increase in margin calls; after the market's plunge, these were about ten times their average size and three times greater than the highest previous levels.[26] Several firms had insufficient cash in customers' accounts (that is, they were "undersegregated"). Firms drawing funds from their own capital to meet the shortfall sometimes became undercapitalized; 11 firms received margin calls for a single customer that exceeded that firm's adjusted net capital, sometimes by as much as two-to-one.[23] Investors needed to repay end-of-day margin calls made on October 19 before the opening of the market on October 20. Clearinghouse member firms called on lending institutions to extend credit to cover these sudden and unexpected charges, but the brokerages requesting additional credit began to exceed their credit limit. Banks were also worried about increasing their involvement and exposure to a chaotic market.[27] The size and urgency of the demands for credit placed upon banks was unprecedented.[28] In general, counterparty risk increased as the creditworthiness of counterparties and the value of collateral posted became highly uncertain.[29]

Federal Reserve response

"[T]he response of monetary policy to the crash," according to economist Michael Mussa, "was massive, immediate and appropriate."[30] One day after the crash, the Federal Reserve (Fed) began to act as the lender of last resort to counter the crisis.[31] Its crisis management approach included issuing a terse, decisive public pronouncement; supplying liquidity through open market operations;[32][upper-alpha 2] persuading banks to lend to securities firms; and in a few specific cases, direct action tailored to a few firms' needs.[34]

On the morning of October 20, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan made a brief statement: "The Federal Reserve, consistent with its responsibilities as the Nation's central bank, affirmed today its readiness to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system".[35] Fed sources suggested that the brevity was deliberate, in order to avoid misinterpretations.[32] This "extraordinary"[36] announcement probably had a calming effect on markets[37] that were facing an equally unprecedented demand for liquidity[28] and the immediate potential for a liquidity crisis.[38] The market rallied after that announcement, gaining around 200 points, but the rally was short-lived. By noon the gains had been erased and the slide had resumed.[39]

The Fed then acted to provide market liquidity and prevent the crisis from expanding into other markets. It immediately began injecting its reserves into the financial system via purchases on the open market. On October 20 it injected $17 billion into the banking system through the open market – an amount that was more than 25 percent of bank reserve balances and 7 percent of the monetary base of the entire nation.[40] This rapidly pushed the federal funds rate down by 0.5 percent. The Fed continued its expansive open market purchases of securities for weeks. The Fed also repeatedly began these interventions an hour before the regularly scheduled time, notifying dealers of the schedule change on the evening beforehand. This was all done in a very high-profile and public manner, similar to Greenspan's initial announcement, to restore market confidence that liquidity was forthcoming.[41] Although the Fed's holdings expanded appreciably over time, the speed of expansion was not excessive.[42] Moreover, the Fed later disposed of these holdings so that its long-term policy goals would not be adversely affected.[32]

The Fed successfully met the unprecedented demands for credit[43] by pairing a strategy of moral suasion that motivated nervous banks to lend to securities firms alongside its moves to reassure those banks by actively supplying them with liquidity.[44] As economist Ben Bernanke (who was later to become Chairman of the Federal Reserve) wrote:

The Fed's key action was to induce the banks (by suasion and by the supply of liquidity) to make loans, on customary terms, despite chaotic conditions and the possibility of severe adverse selection of borrowers. In expectation, making these loans must have been a money-losing strategy from the point of view of the banks (and the Fed); otherwise, Fed persuasion would not have been needed.[45]

The Fed's two-part strategy was thoroughly successful, since lending to securities firms by large banks in Chicago and especially in New York increased substantially, often nearly doubling.[46]

International

All of the twenty-three major world markets experienced a sharp decline in October 1987.[47] Stock markets crashed worldwide, first in Asian markets other than Japan, then Europe, then the US, and finally Japan.[48] When measured in United States dollars, eight markets declined by 20 to 29 percent, three by 30 to 39 percent (Malaysia, Mexico and New Zealand), and three by more than 40 percent (Hong Kong, Australia and Singapore).[47][upper-alpha 3] The least affected was Austria (a fall of 11.4 percent) while the most affected was Hong Kong with a drop of 45.8 percent. Out of twenty-three major industrial countries, nineteen had a decline greater than 20 percent.[50] Worldwide losses were estimated at US$1.71 trillion.[2] The severity of the crash sparked fears of extended economic instability[3] or even a reprise of the Great Depression.[4]

United Kingdom

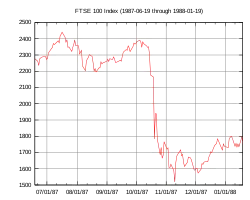

On Friday, October 16, all the markets in London were unexpectedly closed due to the Great Storm of 1987. After they re-opened, the speed of the crash accelerated. By midday, the Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index (FTSE 100) had fallen 296 points, a 14 percent drop.[51] It was down 23 percent in two days, roughly the same percentage that the NYSE dropped on the day of the crash. Stocks then continued to fall, albeit at a less precipitous rate, until reaching a trough in mid-November at 36 percent below its pre-crash peak. Stocks did not begin to recover until 1989.[52]

Japan

In Japan, the October 1987 crash is sometimes referred to as "Blue Tuesday", because of the time zone difference, and its effects were relatively mild.[2] According to economist Ulrike Schaede, the initial market break was severe: the Tokyo market declined 14.9 percent in one day, and Japan's losses of US$421 billion ranked next to New York's $500 billion, out of a worldwide total loss of $1.7 trillion. However, systemic differences between the US and Japanese financial systems led to significantly different outcomes during and after the crash on Tuesday, October 20. In Japan the ensuing panic was no more than mild at worst: the Nikkei 225 Index returned to its pre-crash levels after only five months. Other global markets performed less well in the aftermath of the crash, with New York, London and Frankfurt all needing more than a year to achieve the same level of recovery.[53]

Several of Japan's distinctive institutional characteristics already in place at the time, according to economist David D. Hale, helped dampen volatility. These included trading curbs such as a sharp limit on price movements of a share of more than 10 to 15 percent; restrictions and institutional barriers to short-selling by domestic and international traders; frequent adjustments of margin requirements in response to changes in volatility; strict guidelines on mutual fund redemptions; and actions of the Ministry of Finance to control the total shares of stock and exert moral suasion on the securities industry.[54] An example of the latter occurred when the ministry invited representatives of the four largest securities firms to tea in the early afternoon of the day of the crash.[55] After their visit to the ministry, these firms made large purchases of stock in Nippon Telegraph and Telephone.[55]

Hong Kong

The worst decline among world markets was in Hong Kong, where share values dropped by 45.8 percent.[50] In its biggest-ever single fall, the Hang Seng Index of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange fell by 420.81 points, eliminating HK$65 billion' (10 percent) of its share value.[56] Noting the continued fall of New York markets on their next trading day and fearing steep drops or total collapse of their own exchanges, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange Committee and the committee of the Futures Exchange announced the following morning that both would be closed. Their closure lasted for four working days.[57] Their decision was motivated in part by the high risk that a market collapse would have serious consequences for the entire financial system of Hong Kong, and perhaps result in rioting, with the added threat of intervention by the army of the People's Republic of China.[58] According to Neil Gunningham, a further motivation was brought on by a significant conflict of interest: many of these committee members were themselves futures brokers, and their firms were in danger of substantial defaults from their clients.[57]

Although the stock exchange was in distress, structural flaws in the futures exchange, which was then the world's most heavily traded outside the U.S., were at the heart of the greater financial crisis.[56] The structure of the Hong Kong Futures Exchange differed greatly from many other exchanges around the world. In many countries, large institutional investors dominate the market.[59] Their principal motivation for futures transactions is hedging.[60] In Hong Kong, the market itself, as well as many of its traders and brokers, was inexperienced. It was composed heavily of small, local investors who were relatively uninformed and unsophisticated, had only a short-term commitment to the market, and whose goals were primarily speculative rather than hedging. Among all parties involved, there was little or no expectation of the possibility of a crash or a steep decline or understanding of the consequences of such a fall.[61] In fact, speculative investing that depended on the bull market to continue was prevalent among individual investors, often including the brokers themselves.[62]

The key shortcomings of the futures exchange, however, were mismanagement and a failure of regulatory diligence and design. These failures were particularly grave in the area of credit control. In Hong Kong, the approach to credit involved a system of margins and margin calls plus a Guarantee Corporation backed by a guarantee fund. Although on paper the Hong Kong exchange's margin requirements were in line with those of other major markets, in practice brokers regularly extended credit with little regard for risk. In a lax, freewheeling and fiercely competitive environment, margin requirements were routinely cut in half and sometimes ignored altogether. Hong Kong also had no suitability requirements that would force brokers to screen their customers for ability to repay any debts.[63] The absence of oversight creates an imbalance of risk due to moral hazard: it becomes profitable for traders with low cash reserves to speculate in futures, reaping benefits if they speculate correctly, but simply defaulting if their hunches are wrong.[64] If there is a wave of dishonored contracts, brokers become liable for their clients' losses, potentially facing bankruptcy themselves.[65] Finally, the Guarantee Corporation was severely underfunded, with capital on hand of only HK$15 million (US$2 million). That amount was obviously inadequate for dealing with any large number of clients' defaults in a market trading around 14,000 contracts a day, with an underlying value of HK$4.3 billion.[66]

The crash initially left about 36,400 contracts worth HK$6.7 billion [US$1 billion] outstanding. As late as April 1988, HK$800 million had not been settled.[67] According to Neil Gunningham, the accumulative impact was nearly fatal to the Hong Kong futures market: "Whereas futures exchanges elsewhere [in the world] emerged from the crash with only minor casualties, the crisis in Hong Kong has resulted, at least in the short term, in the virtual demolition of the Futures Exchange."[68] Finally, in the interest of preserving political stability and public order, the Hong Kong government was forced to rescue the Guarantee Fund by providing a bail-out package of HK$4 billion dollars.[69]

New Zealand

The crash of the New Zealand stock market was notably long and deep, continuing its decline for an extended period after other global markets had recovered.[70] Unlike other nations, moreover, for New Zealand the effects of the October 1987 crash spilled over into its real economy, contributing to a prolonged recession.[71]

The effects of the worldwide economic boom of the mid-1980s had been amplified in New Zealand by the relaxation of foreign exchange controls and a wave of banking deregulation. Deregulation in particular suddenly gave financial institutions considerably more freedom to lend, though they had little experience in doing so.[72] The finance industry was in a state of increasing optimism that approached euphoria.[73] This created an atmosphere conducive to greater financial risk taking including increased speculation in the stock market and real estate. Foreign investors participated, attracted by New Zealand's relatively high interest rates. From late 1984 until Black Monday, commercial property prices and commercial construction rose sharply, while share prices in the stock market tripled.[72]

New Zealand's stock market fell nearly 15 percent on the first day.[74] In the following three-and-a-half months, the value of its market shares was cut in half.[75] By the time it reached its trough in February 1988, the market had lost 60 percent of its value.[74] The financial crisis triggered a wave of deleveraging with significant macro-economic consequences. Investment companies and property developers began a fire sale of their properties, partially to help offset their share price losses, and partially because the crash had exposed overbuilding. Moreover, these firms had been using property as collateral for their increased borrowing. When property values collapsed, the health of balance sheets of lending institutions was damaged.[74]

Holding onto a disinflationary stance, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand declined to loosen monetary policy – which would have helped firms settle their obligations and remain in operation.[76] As the harmful effects spread over the next few years, major corporations and financial institutions went out of business, and the banking systems of New Zealand and Australia were impaired, contributing to a "long recession".[77] Access to credit was reduced.[74] In fact, because of legislation requiring the Reserve Bank of New Zealand to achieve an inflation rate no higher than 2 percent by 1993, interest rates were volatile, with multiple increases.[78] The combination of these contributed significantly to a long recession running from 1987 until 1993.[74]

Causes

Discussions of the causes of the Black Monday crash focus on two theoretical models, which differ in whether they emphasise on variables that are exogenous or endogenous. The first searches for exogenous factors, such as significant news events, that affect or "trigger" investor behavior. The second, "cascade theory" or "market meltdown", attempts to identify endogenous internal market dynamics and interactions of systemic variables or trading strategies[79] such that an order imbalance leads to a price change, this price change in turn leads to further order imbalance, which leads to further price changes, and so on in a spiralling cascade.[80] It is possible that both could occur, if a trigger sets off a cascade.[79]

Market forces

Several events have been cited as potential triggers for the initial fall in stock prices. One of these was a proposed tax change that would make corporate takeovers more costly.[81] However, Nobel-prize winning economist Robert J. Shiller surveyed 889 investors (605 individual investors and 284 institutional investors) immediately after the crash regarding several aspects of their experience at the time. Only three institutional investors and no individual investors reported a belief that the news regarding proposed tax legislation was a trigger for the crash.[82]

Other factors often cited include a general feeling that stocks were overvalued and were certain to undergo a correction, the decline of the dollar, persistent trade and budget deficits, and rising interest rates.[81] According to Shiller, the most common responses to his survey were related to a general mindset of investors at the time: a "gut feeling" of an impending crash", perhaps driven by excessive debt.[82] This aligns with an account suggested by economist Martin Feldstein, who has made the argument that several of these institutional and market factors exerted pressure in an environment of general anxiety.[83] Feldstein suggests that the stock market was in a speculative bubble that kept prices "too high by historic and sustainable standards".[84] The real economy was doing well, profits and earnings were rising, but stock prices were rising faster than the underlying profits would warrant. These capital gains created high price-earnings ratios that were unsupportable.[83] There was a common perception that the market was overpriced, and that a correction was certain to occur.[9] At the same time tight monetary policy and a market expectation of continued tightening were driving up interest rates. Bad trade figures from August were announced in October. This created an anticipation that the Fed would raise interest rates again. With the stock market appearing overextended and interest rates rising, a switch from stocks to bonds began to appear increasingly attractive.[83] Yet investors were also hesitant to make this move: "...everybody knew the market was overpriced, but everybody was greedy and didn't want to miss out on a continuation of the wonderful rise that had been going on since the beginning of the year. But they were very, very nervous".[85] As a final catalyst, there was also concern that portfolio insurance would greatly accelerate any drop into an avalanche whenever it began. A return to equilibrium was thus inevitable, but when the bubble burst, the combination of portfolio selling, and significant market nervousness brought a sharp crash.[83]

A second explanation for the crash lies in a crisis of confidence in the dollar created by uncertainties regarding the viability of the Louvre Accord.[86] International investment in the US stock market had expanded significantly in the prolonged bull market. However, trade and budget deficits were bringing both downward pressure on the dollar and an expectation of higher interest rates. These factors and others motivated the industrialized nations (and in particular, the US, Japan and West Germany) to reach the Louvre agreement with several related goals in mind, one of which was to keep a floor beneath the value of the dollar while holding exchange rates within a specified band or reference range of one another. However, the market had limited confidence in the willingness of governments to abide by these agreements.[87] The central banks of Japan and West Germany had been vocal about their fears of rising inflation; this created an expectation that these countries would raise interest rates to reduce liquidity and quell inflationary pressures. If those countries raised their rates, then in order to keep all countries within the agreed range of each other, the US would be expected to raise rates as well.[88] When the Bundesbank followed through on its remarks and took steps to raise short-term interest rates, US Treasury Secretary James Baker publicly clashed with the Germans, making remarks that were interpreted as a threat to devalue the dollar.[89] Even under normal circumstances, a weaker dollar would tend to make US stocks look less attractive to foreign investors.[90] These remarks, however, created shock and panic among investors outside the US.[91] They raised the prospect of a currency war, or even the collapse of the dollar,[92] an anonymous senior Reagan administration later summarized the fear and uncertainty in investor's minds after Baker's statement:

...wait a minute. If [Baker] is using it as a lever [to influence the Bundesbank] and we believe it won't work, there is no bottom. If he isn't using it as a lever, and he just actually wants the dollar to go down, then there is no stability. And if he isn't clear whether it is one or the other of those, then he doesn't understand his own system and his own business, and we'll have a problem of confidence.[93]

In this account, the result was a punishing selloff that started in Asia and spread to Europe and the US as markets opened up across the world.[94]

De-linked markets and index arbitrage

Under normal circumstances the stock market and those of its main derivatives–futures and options–are functionally a single market, given that the price of any particular stock is closely connected to the prices of its counterpart in both the futures and options market.[95] Prices in the derivative markets are typically tightly connected to those of the underlying stock, though they differ somewhat (as for example, prices of futures are typically higher than that of their particular cash stock).[96] During the crisis this link was broken.[97]

When the futures market opened while the stock market was closed, it created a pricing imbalance: the listed price of those stocks which opened late had no chance to change from their closing price of the day before. The quoted prices were thus "stale" and did not reflect current economic conditions; they were generally listed higher than they should have been (and dramatically higher than their respective futures, which are typically higher than stocks).[98]

The decoupling of these markets meant that futures prices had temporarily lost their validity as a vehicle for price discovery; they no longer could be relied upon to inform traders of the direction or degree of stock market expectations. This had harmful effects: it added to the atmosphere of uncertainty and confusion at a time when investor confidence was sorely needed; it discouraged investors from "leaning against the wind" and buying stocks since the discount in the futures market logically implied that investors could wait and purchase stocks at an even lower price; and it encouraged portfolio insurance investors to sell in the stock market, putting further downward pressure on stock prices.[99]

The gap between the futures and stocks was quickly noted by index arbitrage traders who tried to profit through sell at market orders. Index arbitrage, a form of program trading,[100] added to the confusion and the downward pressure on prices:[16]

...reflecting the natural linkages among markets, the selling pressure washed across to the stock market, both through index arbitrage and direct portfolio insurance stock sales. Large amounts of selling, and the demand for liquidity associated with it, cannot be contained in a single market segment. It necessarily overflows into the other market segments, which are naturally linked. There are, however, natural limits to intermarket liquidity which were made evident on October 19 and 20.[101]

Although arbitrage between index futures and stocks placed downward pressure on prices, it does not explain why the surge in sell orders that brought steep price declines began in the first place.[102] Moreover, the markets "performed most chaotically" during those times when the links that index arbitrage program trading creates between these markets was broken.[103]

Portfolio insurance hedges

Portfolio insurance is a hedging technique which seeks to manage risk and limit losses by buying and selling financial instruments (for example, stocks or futures) in reaction to changes in market price rather than changes in market fundamentals. Specifically, they buy when the market is rising, and sell as the market falls, without regard for any fundamental information about why the market is rising or falling.[104] Thus, it is an example of an "informationless trade"[105] that has the potential to create a market-destabilizing feedback loop.[106]

This strategy became a source of downward pressure when portfolio insurers whose computer models noted that stocks opened lower and continued their steep price decline. The models recommended even further sales.[16] The potential for computer-generated feedback loops that these hedges created has been discussed as a factor compounding the severity of the crash, but not as an initial trigger.[107] Economist Hayne Leland argues against this interpretation, suggesting that the impact of portfolio hedging on stock prices was probably relatively small.[108] Similarly, the report of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange found the influence of "other investors—mutual funds, broker-dealers, and individual shareholders—was thus three to five times greater than that of the portfolio insurers" during the crash.[109] Numerous econometric studies have analyzed the evidence to determine whether portfolio insurance exacerbated the crash, but the results have been unclear.[110] Markets around the world that did not have portfolio insurance trading experienced as much turmoil and loss as the US market.[111] More to the point, the cross-market analysis of Richard Roll, for example, found that markets with a greater prevalence of computerized trading (including portfolio insurance) actually experienced relatively less severe losses (in percentage terms) than those without.[112]

Noise trading

Contemporaneous causality and feedback behavior between markets increased dramatically during this period.[113] In a volatile and uncertain market, investors worldwide[114] were inferring information from changes in stock prices and communication with other investors[115] in a self-reinforcing contagion of fear.[114] This pattern of basing trading decisions on market psychology is often referred to as one form of "noise trading", which occurs when ill-informed investors "[trade] on noise as if it were news".[116] A significant amount of trading takes place based on information which is unquantifiable and potentially irrelevant, such as unsubstantiated rumors or a "gut feeling".[117] Investors vary between seemingly rational and irrational behaviors as they "struggle to find their way between the give and take, between risk and return, one moment engaging in cool calculation and the next yielding to emotional impulses".[118] If noise is misinterpreted as meaningful news, then the reactions of risk-averse traders and arbitrageurs will bias the market, preventing it from establishing prices that accurately reflect the fundamental state of the underlying stocks.[119] For example, on October 19 rumors that the NYSE would close created additional confusion and drove prices further downward, while rumors the next day that two Chicago Mercantile Exchange clearinghouses were insolvent deterred some investors from trading in that marketplace.[120]

A feedback loop of noise-induced-volatility has been cited by some analysts as the major reason for the severe depth of the crash. It does not, however, explain what initially triggered the market break.[121] Moreover, Lawrence A. Cunningham has suggested that while noise theory is "supported by substantial empirical evidence and a well-developed intellectual foundation", it makes only a partial contribution toward explaining events such as the crash of October 1987.[122] Informed traders, not swayed by psychological or emotional factors, have room to make trades they know to be less risky.[123]

Aftermath

After Black Monday, regulators overhauled trade-clearing protocols to bring uniformity to all prominent market products. They also developed new regulatory instruments, known as "trading curbs" or "circuit breakers", allowing exchanges to temporarily halt in instances of exceptionally large price decline; for instance, the DJIA.[124] The curbs were implemented multiple times during the 2020 stock market crash.[125]

Arguably, a second consequence of the crash was the death of the Louvre Accord.[126] Its intent was already being defeated by market forces as early as April of that year. Then the response of the Reagan administration to the crash was to deliberately let both interest rates and the value of the dollar fall to provide liquidity. They later resumed some interventions on behalf of the dollar until December 1988, but eventually it became clear that "international currency coordination of any kind, including a target zone, is not possible."[127]

The crash of 1987 altered implied volatility patterns that arise in pricing financial options. Equity options traded in American markets did not show a volatility smile before the crash but began showing one afterward.[128]

See also

Footnotes

- Explanations [for the extended bull market] include "...improved earnings growth prospects, a decrease in the equity risk premium... [and] substantial undervaluation of equities when inflation is high, as in the early 1980s. The bull market.. [was] in part a correction from this previous level of undervaluation."[7]

- Discount window borrowing did not play a major role in the Federal Reserve's response to the crisis.[33]

- The markets were: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, West Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.[47] China did not have major stock markets at the time. The Shanghai Stock Exchange opened in December 1990 and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in April 1991.[49]

References

- Bates 1991, p. 1363; Seyhun 1990, p. 1009.

- Schaede 1991, p. 42.

- Group of 33.

- Lobb 2007.

- Grant 1997, p. 330.

- Hinden 1989.

- Ritter & Warr 2002, pp. 29–30.

- General Accounting Office 1988, p. 14.

- General Accounting Office 1988, p. 36.

- Carlson 2007, p. 6; General Accounting Office 1988, p. 41; Malliaris & Urrutia 1992, p. 354.

- Bernhardt & Eckblad 2013, note 5.

- Roll 1988, p. 22.

- Lindsey & Pecora 1998, pp. 3–4.

- Brady Report 1988, p. 29.

- Carlson 2007, p. 8, note 11.

- Carlson 2007, p. 8.

- Brady Report 1988, p. 1.

- Quennouëlle-Corre 2021, p. 165; Carlson 2007, pp. 8–9.

- Carlson 2007, pp. 8–9.

- General Accounting Office 1988, p. 55.

- Carlson 2007, p. 9; Bernanke 1990, p. 146.

- Mishkin 1988, pp. 29–30.

- Brady Report 1988, Study VI, p. 73

- Cecchetti & Disyatat 2009, p. 1; Carlson 2007, p. 20.

- Glauber 1988, p. 10.

- Brady Report 1988, Study VI, p. 71; Carlson 2007, pp. 12–13.

- Carlson 2007, pp. 12–13.

- Garcia 1989, p. 153.

- Kohn 2006; Bernanke 1990, pp. 146–147.

- Mussa 1994, p. 127.

- Mishkin 1988, p. 31 "the Fed has performed its role of lender of last resort so admirably in the recent stock market crash episode..."

- Garcia 1989, p. 151.

- Carlson 2007, p. 18, note 17; Garcia 1989, pp. 151–153 "... in conversations, Federal Reserve officials repeatedly stressed that they did not use the discount window during the crash".

- Bernanke 1990, p. 148.

- Greenspan 1987, p. 915.

- Mishkin 1988, p. 30.

- Carlson 2007, p. 10.

- Mishkin 1988, pp. 29–30; Brady Report 1988, Study VI, p. 73

- Toporowski 1993, p. 125; Metz 1992, p. 134.

- Mussa 1994, p. 128.

- Carlson 2007, pp. 17–18.

- Carlson 2007, p. 18.

- Carlson 2007, pp. 13–14; Garcia 1989, p. 153.

- Garcia 1989, p. 153; Bernanke 1990, p. 149.

- Bernanke 1990, p. 149.

- Carlson 2007, p. 14; Bernanke 1990, p. 149.

- Roll 1988, p. 20 (table 1), 21.

- Roll 1988, p. 19.

- Huang, Yang & Hu 2000, p. 284.

- Sornette 2003, p. 4.

- Brady Report 1988, pp. III-22, III-16.

- Roberts 2008, pp. 53–54.

- Schaede 1991, pp. 42–45.

- Hale 1988, pp. 182–183.

- Schaede 1991, p. 45.

- Gunningham 1990, p. 2.

- Gunningham 1990, p. 3.

- Gunningham 1990, pp. 18–19, 40.

- Gunningham 1990, p. 44.

- Gunningham 1990, p. 8.

- Gunningham 1990, pp. 16, 38, 43.

- Gunningham 1990, pp. 14–15, 43.

- Gunningham 1990, pp. 16–18, 30–31, 38–39.

- Bernanke 1990, p. 141.

- Gunningham 1990, p. 15.

- Gunningham 1990, pp. 2 note 3, 18.

- Gunningham 1990, pp. 15, 17 note 46.

- Gunningham 1990, p. 39.

- Gunningham 1990, p. 19.

- Grant 1997, p. 329.

- Hunt 2009, p. 36; Grant 1997, p. 337.

- Hunt 2009, p. 35; Reddell & Sleeman 2008, p. 14.

- Hunt 2009, p. 35.

- Hunt 2009, p. 36.

- Reddell & Sleeman 2008, p. 14.

- Grant 1997, p. 330; Hunt 2009, p. 36.

- Reddell & Sleeman 2008, p. 14; Hunt 2009, p. 36.

- Fuerbringer 1991.

- Headrick 1992, p. 317.

- Blume, Mackinlay & Terker 1989, p. 837.

- Markham & Stephanz 1988, pp. 2007, 2011.

- Shiller 1988, pp. 292–293.

- Feldstein et al. 1988, pp. 337–339.

- Feldstein et al. 1988, p. 337.

- Feldstein et al. 1988, p. 338.

- Cohen 2007, p. 65; Feldstein et al. 1988, p. 343.

- Kandiah 1999, p. 134.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York 1987–1988, pp. 50–51.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York 1987–1988, p. 51; Bernhardt & Eckblad 2013; Cohen 2007, pp. 64–65.

- Rees 2007, p. 48.

- Kandiah 1999, p. 135; Schaede 1991, p. 42.

- Meltzer 1989, p. 19 note 3.

- Funabashi 1989, p. 235.

- Forsyth 2017.

- Kleidon & Whaley 1992, pp. 851–852; Brady Report 1988, p. 55, 57.

- Kleidon & Whaley 1992, p. 851.

- Kleidon & Whaley 1992, pp. 851–852.

- Kleidon & Whaley 1992, pp. 859–860.

- Macey, Mitchell & Netter 1988, p. 832.

- Carlson 2007, p. 5.

- Brady Report 1988, p. 56.

- Harris 1988, p. 933.

- Miller et al. 1989, pp. 12–13.

- Leland 1988, p. 80; Leland 1992, pp. 154–156.

- Macey, Mitchell & Netter 1988, p. 819, note 84.

- Leland 1992, pp. 155–156.

- Brady Report 1988, p. v.

- Leland 1988, pp. 83–84.

- Miller et al. 1989, p. 6.

- MacKenzie 2004, p. 10.

- Miller et al. 1989, pp. 6–7.

- Roll 1988, pp. 29–30.

- Malliaris & Urrutia 1992, pp. 362–363.

- King & Wadhwani 1990, p. 26.

- Shiller 1987, p. 23.

- Black 1988, pp. 273–274.

- Gaffikin 2007, p. 7.

- Bernstein 1996, p. 287.

- Cunningham 1994, p. 10.

- Carlson 2007, pp. 9, 10, 17.

- Shleifer & Summers 1990, p. 30; Black 1988, pp. 273–274.

- Cunningham 1994, pp. 3, 10.

- Cunningham 1994, p. 26.

- Bernhardt & Eckblad 2013, p. 3; Lindsey & Pecora 1998.

- Shieber 2020.

- Reinalda 2009, p. 562; Ito 2016, pp. 92–95.

- Ito 2016, pp. 92–95.

- Hull 2003, p. 335.

Sources

- Bates, David S. (1991). "The Crash of '87: Was It Expected? The Evidence from Options Markets". The Journal of Finance. 46 (3): 1009–1044. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1991.tb03775.x.

- Bernanke, Ben S. (1990). "Clearing and Settlement during the Crash". The Review of Financial Studies. 3 (1): 133–151. doi:10.1093/rfs/3.1.133. S2CID 10499111.

- Bernhardt, Donald; Eckblad, Marshall (2013). "Black Monday: The Stock Market Crash of 1987". Federal Reserve History.

- Bernstein, Peter L. (1996). Against the gods: the remarkable story of risk. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471295631. OCLC 34411005.

- Black, Fischer (1988). "An Equilibrium Model of the Crash". NBER Macroeconomics Annual. 3: 269–275. doi:10.1086/654089.

- Blume, Marshall E.; Mackinlay, A. Craig; Terker, Bruce (September 1989). "Order Imbalances and Stock Price Movements on October 19 and 20, 1987". The Journal of Finance. 44 (4): 827–848. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1989.tb02626.x. JSTOR 2328612.

- Carlson, Mark A. (2007). A Brief History of the 1987 Stock Market Crash with a Discussion of the Federal Reserve Response (PDF) (Technical report). Finance and Economics Discussion Series. Federal Reserve Board. 13.

- Cecchetti, Stephen Giovanni; Disyatat, Piti (2009). Central Bank Tools and Liquidity Shortages (PDF) (Technical report). Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- Cohen, Benjamin J. (2007). Global Monetary Governance. Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0203962589. OCLC 779908166.

- Cunningham, Lawrence A. (1994). "From Random Walks to Chaotic Crashes: The Linear Genealogy of the Efficient Capital Market Hypothesis". The George Washington Law Review. OCLC 818988457.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York (1987–1988). "Treasury and Federal Reserve Foreign Exchange Operations". Federal Reserve Bank of New York Quarterly Review. 12 (Winter): 48–53. OCLC 1286478945.

- Feldstein, Martin; Modigliani, Franco; Sinai, Allen; Solow, Robert (1988). "Black Monday in Retrospect and Prospect: A Roundtable". Eastern Economic Journal. 14 (4): 337–348. OCLC 42629270.

- Forsyth, Randall W. (October 20, 2017). "Currencies, Not Computers, Caused Black Monday". Barron's. ISSN 1077-8039. Retrieved May 7, 2023.(subscription required)

- Fuerbringer, Jonathan (January 27, 1991). "World Markets; A Warning Flag Over New Zealand". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522.

- Funabashi, Yōichi (1989). Managing the Dollar: From the Plaza to the Louvre. Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics. ISBN 0-88132-071-4.

- Gaffikin, Michael (2007). "Accounting Research and Theory: The Age of Neo-Empiricism". Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal. 1 (1): 1–17. doi:10.14453/aabfj.v1i1.1. S2CID 54659656.

- Garcia, Gillian (1989). "The Lender of Last Resort in the Wake of the Crash". The American Economic Review. 79 (2): 151–155. OCLC 847300958.

- General Accounting Office, Financial Markets (January 1988). Preliminary Observations on the October 1987 Crash (PDF) (Report).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Glauber, Robert R. (1988). "After Black Monday: An Interview with Robert R. Glauber". G.A.O Journal: A Quarterly Sponsored by the U.S. General Accounting Office. 2: 4–11. OCLC 647060020.

- Grant, David Malcolm (1997). Bulls, Bears and Elephants: A History of the New Zealand Stock Exchange. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University Press. ISBN 0-86473-308-9.

- Greenspan, Alan (1987). "Statement by Chairman Greenspan on Providing Liquidity to the Financial System". Federal Reserve Bulletin. ISSN 0014-9209.

- "Group of 7, Meet the Group of 33". The New York Times. December 26, 1987. OCLC 1645522.

- Gunningham, Neil (Winter 1990). "Moving the Goalposts: Financial Market Regulation in Hong Kong and the Crash of October 1987". Law and Social Inquiry. 15 (1): 1–48. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.1990.tb00274.x. S2CID 154680095.

- Hale, David D. (August 17–19, 1988). Commentary on 'Policies to Curb Stock Market Volatility' (PDF). Symposium on Financial Market Volatility. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. pp. 167–173. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- Harris, Lawrence (1988). "Dangers of Regulatory Overreaction to the October 1987 Crash". Cornell Law Review. 74: 927–42. ISSN 0010-8847.

- Headrick, Thomas E. (October 1992). "Expert Policy Analysis and Bureaucratic Politics: Searching for the Causes of the 1987 Stock Market Crash". Law & Policy. 14 (4): 313–336. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9930.1992.tb00088.x.

- Hinden, Stan (July 23, 1989). "A More Sober DOW Nears Its Peak". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- Huang, Bwo-Nung; Yang, Chin-Wei; Hu, John Wei-Shan (2000). "Causality and Cointegration of Stock Markets among the United States, Japan and the South China Growth Triangle". International Review of Financial Analysis. 9 (3): 281–297. doi:10.1016/S1057-5219(00)00031-4.

- Hunt, Chris (2009). "Banking Crises in New Zealand – an Historical Perspective" (PDF). Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin. 72 (4): 26–41. ISSN 0112-871X. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Hull, John C. (2003). Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-046592-5.

- Ito, Takatoshi (2016). "The Plaza Accord and Japan: Reflections on the 30th anniversary". In Bergsten, C. Fred; Green, Russell A. (eds.). International monetary cooperation: Lessons from the Plaza Accord after thirty years. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics. pp. 73–104. ISBN 978-0881327113.

- Kandiah, Michael David (1999). "The October 1987 Stock Market Crash –Ten Years On". Contemporary British History. 13 (1): 133–140. doi:10.1080/13619469908581518.

- King, Mervyn A.; Wadhwani, Sushil (1990). "Transmission of Volatility between Stock Markets" (PDF). The Review of Financial Studies. 3 (1): 5–33. doi:10.1093/rfs/3.1.5. S2CID 154421440.

- Kohn, Donald L. (May 18, 2006). The Evolving Nature of the Financial System: Financial Crises and the Role of the Central Bank (Speech). Conference on New Directions for Understanding Systemic Risk. Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

- Kleidon, Allan W.; Whaley, Robert E. (1992). "One Market? Stocks, Futures, and Options During October 1987". The Journal of Finance. 47 (3, Papers and Proceedings of the Fifty-Second Annual Meeting of the American Finance Association, New Orleans, Louisiana January 3–5, 1992): 851–877. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb03997.x. JSTOR 2328969.

- Leland, Hayne E. (1988). "Portfolio Insurance and October 19th". California Management Review. 30 (44): 80–89. doi:10.2307/41166528. JSTOR 41166528. S2CID 156790783.

- Leland, Hayne E. (October 14, 1992). "Portfolio Insurance". In Eatwell, John; Milgate, Murray; Newman, Peter (eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Money and Finance: 3 Volume Set. New York: The Stockton Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-041-4.

- Lindsey, Richard R.; Pecora, Anthony P. (1998). "Ten Years After: Regulatory Developments in the Securities Markets since the 1987 Market Break" (PDF). Securities and Exchange Commission Historical Society. pp. 101–132. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- Lobb, Annelena (October 15, 2007). "Looking Back at Black Monday:A Discussion With Richard Sylla". The Wall Street Journal. OCLC 781541372.

- Macey, Jonathan R.; Mitchell, Mark; Netter, Jeffry (1988). "Restrictions on Short Sales: An Analysis of the Uptick Rule and Its Role in View of the October 1987 Stock Market Crash". Cornell Law Review. 74. ISSN 0010-8847.

- MacKenzie, Donald (2004). "The Big, Bad Wolf and the Rational Market: Portfolio Insurance, the 1987 Crash and the Performativity of Economics". Economy and Society. 33 (3): 303–334. doi:10.1080/0308514042000225680. S2CID 143644137.

- Malliaris, Anastasios G.; Urrutia, Jorge L. (1992). "The International Crash of October 1987: Causality Tests". Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. 27 (3): 353–364. doi:10.2307/2331324. JSTOR 2331324. S2CID 56354928.

- Markham, Jerry W.; Stephanz, Rita McCloy (1988). "The Stock Market Crash of 1987 – The United States Looks at New Recommendations". The Georgetown Law Journal. 76: 1993–2043. ISSN 0016-8092.

- Meltzer, Alan H. (1989). "Overview". In Kamphuis, Robert W.; Kormendi, Roger C.; Watson, J. W. Henry (eds.). Black Monday and the Future of Financial Markets. Chicago: Dow Jones-Irwin. pp. 1–33. ISBN 1556231385.

- Metz, Tim (1992). "The Crash". In Fadiman, Mark (ed.). Rebuilding Wall Street: After the Crash of'87, Fifty Insiders Talk about Putting Wall Street Together Again. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall Direct. pp. 132–136. ISBN 978-0137530137.

- Miller, M; Hawke, J; Malkiel, B; Scholes, M (1989). Final Report of the Committee of Inquiry appointed by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange to Examine the Events surrounding October 1987. The Black Monday and the Futures of Financial Markets (Report).

- Mishkin, Frederic S. (August 17–19, 1988). Commentary on 'Causes of Changing Financial Market Volatility'. Symposium on Financial Market Volatility. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. pp. 23–32. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- Mussa, Michael (1994). "Monetary Policy: Michael Mussa". In Feldstein, Martin S. (ed.). American Economic Policy in the 1980s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 81–159. ISBN 0226240932. OCLC 28506978.

- Quennouëlle-Corre, Laure (2021). "The 1987 Stock Exchange Crash in Historical Perspective: A Crisis Denied?". Remembering and Learning from Financial Crises. Oxford University Press. pp. 165–183. ISBN 978-0-19-264395-7.

- Reddell, Michael; Sleeman, Cath (2008). "Some Perspectives on Past Recessions" (PDF). Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin. 71 (2): 5–21. ISSN 0112-871X. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- Rees, Matthew (2007). "The Hunt for Black October: With the Anniversary of the Worst One-Day Decline in US Stock Market History Approaching, Matthew Rees Set Out To Find Its Cause. And Determine Whether It Can Happen Again". The American (Washington, DC). 1 (6): 46–61. ISSN 1932-8117.

- Reinalda, Bob (2009). Routledge History of International Organizations: from 1815 to the Present Day. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415476249.

- Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms. United States Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms (Technical report). United States Government Publishing Office. 1988.

- Ritter, Jay R.; Warr, Richard S. (2002). "The Decline of inflation and the Bull Market of 1982–1999". Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. 37 (1): 29–61. doi:10.2307/3594994. JSTOR 3594994. OCLC 781598756. S2CID 154940716.

- Roberts, Richard (2008). The City: A Guide to London's Global Financial Centre. London: Profile Books, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86197-858-5.

- Roll, Richard (1988). "The International Crash of October 1987". Financial Analysts Journal. 44 (5): 19–35. doi:10.2469/faj.v44.n5.19.

- Schaede, Ulrike (1991). "Black Monday in New York, Blue Tuesday in Tokyo: The October 1987 Crash in Japan". California Management Review. 33 (2): 39–57. doi:10.2307/41166649. JSTOR 41166649. S2CID 154808689.

- Seyhun, H. Nejat (1990). "Overreaction or Fundamentals: Some Lessons from Insiders' Response to the Market Crash of 1987". The Journal of Finance. 45 (5): 1363–1388. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1990.tb03719.x.

- Shiller, Robert J. (1987). Investor Behavior in the October 1987 Stock Market Crash: Survey Evidence (PDF) (Technical report). NBER Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2446.

- Shieber, Jonathan (March 16, 2020). "Stock Markets Halted for Unprecedented Third Time due to Coronavirus Scare". TechCrunch. OCLC 1058545022.

- Shiller, Robert J. (1988). "Portfolio Insurance and Other Investor Fashions as Factors in the 1987 Stock Market Crash". NBER Macroeconomics Annual. 3: 287–297. doi:10.1086/654091.

- Shleifer, Andrei; Summers, Lawrence H. (1990). "The Noise Trader Approach to Finance". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 4 (2): 19–33. doi:10.1257/jep.4.2.19.

- Sornette, Didier Sornette (2003). "Critical Market Crashes". Physics Reports. 378 (1): 1–98. arXiv:cond-mat/0301543. Bibcode:2003PhR...378....1S. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(02)00634-8. S2CID 12847333.

- Toporowski, Jan (1993). The Economics of Financial Markets and the 1987 Crash. Aldershot, England: Edward Elgar Publishing Company. ISBN 1852788976. OCLC 27895569.

Further reading

- Blakey, George G. (2011). A History of the London Stock Market 1945–2009. Harriman House Limited. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0857191151.

- Bozzo, Albert (October 12, 2007). "Players replay the crash". CNBC.

- Browning, E.S. (October 15, 2007). "Exorcising Ghosts of Octobers Past". The Wall Street Journal. OCLC 781541372.

- Furbush, Dean (2002). "Program Trading". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (1st ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty. OCLC 317650570, 50016270, 163149563

- Goodhart, Charles (August 17–19, 1988). The International Transmission of Asset Price Volatility. Symposium on Financial Market Volatility. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. pp. 79–120. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- Greenspan, Alan (2008) [2007]. The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World. Penguin Books. pp. 104–110. ISBN 978-0143114161.

- Maley, Matt (October 16, 2017). "The real reason for 1987 crash, as told by a Salomon Brothers veteran". CNBC.

- Martin, Justin (2000). Greenspan: The Man Behind Money. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. pp. 171–186. ISBN 978-0738202754.

- Sobel, Robert (1988). Panic on Wall Street: A Classic History of America's Financial Disasters – With a New Exploration of the Crash of 1987. E. P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0525484042.

- Woodward, Bob (2000). Maestro: Greenspan's Fed and the American Boom. Simon & Schuster. pp. 36–49. ISBN 978-0743204125.

External links

- "Statement of the G6 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors". University of Toronto G8 Centre. University of Toronto Library. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- CNBC Remembering the Crash of 1987

- Black Monday photographs