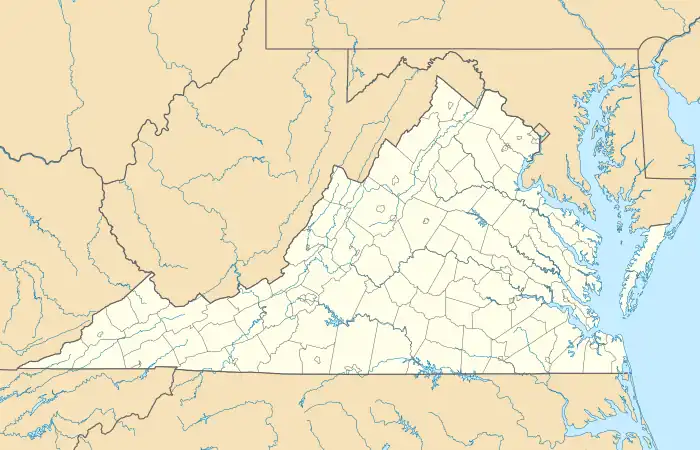

Black Walnut (Clover, Virginia)

Black Walnut is a historic plantation house and farm located near Clover, Halifax County, Virginia. The main house was built in at least three sections beginning about 1774 to 1790. In the 1840s and 1850s, a substantial two-story frame addition was built in two stages parallel to the existing house, along with a connecting hyphen, altogether giving the house an H-shape. The interior features Greek Revival style details.[2]

Black Walnut Plantation | |

Black Walnut Manor House | |

| |

| Location | 2091 Black Walnut Road, Clover, VA 24534 (VA 600, 850 ft. S of jct. with VA 778, in Halifax County, Virginia) |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°51′47″N 78°43′22″W |

| Area | 8 acres (3.2 ha) |

| Built | 1774 |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 91001597 |

| VLR No. | 041-0006 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 29, 1991 [1] |

| Designated VLR | August 21, 1991 [1] |

Also on the property are the contributing brick kitchen, a dairy, a wash-house, two smokehouses, two sheds, a cool-storage building, a privy, a stable, a barn, a slave cabin, a corncrib, two machine sheds, a toolshed, a garage, a late 18th-century schoolhouse, and the family cemetery.[2]

At its peak, Black Walnut Plantation was one of the largest and most successful plantations in Halifax County. The only Civil War battle fought in Halifax County, the Battle of Staunton River Bridge, took place on Black Walnut Plantation in Summer 1864. Confederate troops maintained encampment there during the war alongside up to 800 Confederate slave laborers.[3]

During the September 1939 National Tobacco Festival, Academy Award Winner Mary Pickford visited Black Walnut as Queen of the festival.[4][5]

Early history

The Staunton River Battlefield Project is a collaboration between the Dr. James W. Jordan Archaeology Field School and the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation – Division of State Parks. This research is being undertaken at Staunton River Battlefield State Park. Originally the focus was on the Civil War battle that took place on this site in 1864. Following the work on the Civil War site, the focus shifted to the prehistoric past when the remnants of a Saponi Indian village dating back to the Late Woodland period were discovered at the Randy K. Wade Archeological Site.

To date, more than 100,000 artifacts have been recovered from this site and radiocarbon dating has demonstrated that the site was occupied from approximately A.D. 950 to 1425. Paleo-environmental data has indicated that the site was occupied year-round, rather than seasonally, and it is currently estimated that around 200 people lived at the Wade Site. This research has focused on a variety of questions including subsistence strategy and horticultural development, social organization, mortuary practices, and environment reconstruction.

Some of the more intriguing evidence at the site relates to the variability in the burial practices that may indicate social stratification and a shift from Big Man to Chiefdom social organization. Also of interest is whether the site was actually an island in the Staunton River and whether it may have been one at the time the site was occupied. Future fieldwork will continue to seek answers to these and other questions.[6]

Initial survey and settlement, 1700s

In 1741, Richard Randolph of Henrico County was granted a land patent of 10,300 acres situated along both shores of the Staunton [Roanoke] River, Licking Hole [Little Roanoke] Creek, and Black Walnut Creek, in what was then Lunenburg County. With the creation of Halifax County in 1752, 3,100 acres of Randolph's original land patent was cut off and annexed to the newly established county. In 1748, Richard devised this parcel to his son, John Randolph. Randolph never resided on this property since the family's primary residence was Henrico County where they owned several plantations along the James River. During this early period, however, the property was referred to as the "Black Walnut Plantation" indicating some type of improvement on the site.

Acquisition by William Sims, 1768

Twenty years later, in June 1768, John Randolph sold the entire 3,100-acre parcel to William Sims of Cornwall Parish, Charlotte County. The deed from John Randolph to William Sims described the tract as being part of a larger tract known as "Black Walnut Plantation" and a small plantation opposite to the mouth of the Little Roanoke River. William Sims and his brothers, David and Matthew, moved to Halifax County from Charlotte around 1770. During William Sims' brief tenure, tobacco was cultivated as the main crop, along with other crops and livestock. After five years of ownership, William Sims sold his 3,100-acre property to Matthew Sims for five shillings. Matthew Sims settled on part of the property and, in February 1774, surveyed off 1,750 acres and sold it to his brother, David Sims.

Early settlement and land-use, 1770s–1800s

Matthew Sims (1773–1790)

The lands retained by Matthew Sims were established as his homestead, where he built his manor house. The main house, which dates to the 1770s, probably stood as a 1-story or 1+1⁄2-story single-pile, four-room house with interior end chimneys. The earliest documented outbuilding associated with the Black Walnut plantation was constructed southeast of the main house and consisted of a 1+1⁄2-story, wood-frame building (Figure 9). This building terminates in a steeply pitched roof that is sheathed in standing-seam metal. The late-eighteenth-century structure was used as a schoolhouse; the building is still extant on the Black Walnut property.

Matthew took an active role in the Episcopal church, as did many of Halifax County's leading citizens. The boundaries of Halifax County and the Episcopal parish, Antrim, coincided. In 1783 Matthew and several other leading citizens were designated to collect tithes in the western section of the county.[7]

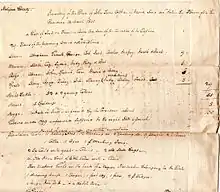

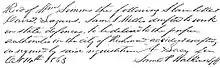

Matthew married Amey (Oney) May of Charlotte County in 1774. Matthew died in 1790 and left behind his wife and nine children. An inventory dated November 1790 shows his estate as including 40 slaves, personal belongings, crops, and livestock. Agricultural crops listed in this inventory included "200 barrels corn, crop of tobo. 1790 supposed 15000" pounds. Livestock included 45 cattle and horses, and 13 hogs. Amey May Sims acquired title to a 325-acre tract of land, including "the mansion house". According to Matthew Sims' inventory, the remaining twenty slaves were divided among his children. His son, Matthew, received "1 Negro man slave, Taylor, 1 Negro woman slave, Page, 2 Negro girls, Julia and Hannah". His daughter, Lettie Sims, was bequeathed "1 Negro man slave, Daniel, 1 boy slave, Lott, 1 girl slave, Dorcas". Charles Sims was left "l Negro man slave, Easop, 1 Negro slave girl, Tamer". Nancey Sims was bequeathed "1 Negro man slave, Davie, 1 Negro girl slave, Jeanney". Martricia received "1 Negro man Slave, Toney, 1 Negro woman Slave, Elie, and child, Visay". Oney was bequeathed "1 Negro boy Slave, Harry; 1 Negro girl Slave, Little Nanney; 1 Negro boy Slave, Ceasar". Elizabeth Sims received three slaves, including "l Negro man Slave, Antony, 1 Negro boy Slave, Emanuel, 1 Negro girl Slave, Unity".[8]

David Sims (1774-1783)

David Sims settled on the 1,750-acre portion of the original Randolph land grant that he purchased from Matthew in 1774. David operated the plantation for a decade, from 1774 until his death in 1783. In January 1774, he married Lettice May from Charlotte County. David established himself as a prominent planter and served as vestryman for Antrim Parish beginning in 1782. When David died in 1783, he left behind his widow and four children, Betsy, Priscilla, Patty, and John. His inventory at the time of his death was quite substantial and included 30 slaves, 70 cows, three oxen, 57 sheep, 59 hogs, 11 horses, household furniture, and farming equipment. Most of his real estate was bequeathed to his son, John, and held in trust until 1803, when he became old enough to operate the plantation. During this period, the plantation continued to produce tobacco, in addition to corn, beef, and pork. A 1797 inventory listed 27 slaves, 39 head of cattle, 90 hogs, 45 young pigs, 35 geese, and several horses.[2]

Land-use and development, 1800s-1890s

John Sims (1803-1852)

John Sims, David Sims' son, was largely responsible for Black Walnut's success as one of the most prosperous farms in Halifax County. John Sims received his inheritance in 1803, which included the 1,500-acre tract of land and 29 slaves. John Sims acquired additional landholdings in the county throughout the 1800s, becoming one of the largest landowners in the area. Only three other landowners, William Logan, Richard Logan, and John Coleman, held more land by 1850. John Sims operated the Black Walnut plantation for the next five decades, until his death in 1852.

John Sims received his formal education at Hampden-Sydney. In 1809, he had acquired the 325-acre tract and mansion from his uncle Matthew's heirs. The following year, John Sims married Maria Wilson Clark. During their marriage, they resided at the Black Walnut plantation house. John and Maria Sims had four children: Mary Elizabeth, Phebe Ann, Mary Wilson, and William Howson. In 1815, their residence was valued at $2,000.00.

Interior appointments included 8 calico window curtains; 1 carpet; 12 chairs with gold leaf; 1 piano; 1 sideboard; 1 mahogany bureau; 1 bureau; 1 chest of drawers; 1 clock; and 2 silver salvers. Maria Sims died in July 1822, and John Sims devoted the rest of his life to rearing his four children and managing the large estate.[9]

The Black Walnut Plantation reached its heyday by the mid-nineteenth century under the careful management of John Sims. The plantation in 1850 was described as consisting of 1,000 acres of improved land and 1,200 acres of unimproved land. His prosperity also was illustrated by the significant increase in slaveholdings. Between 1820 and 1840, John Sims increased his slaveholdings from 77 slaves to 137 slaves. By 1850, his labor force included 150 slaves.

Tobacco was cultivated as the main cash crop, however, the plantation was diversified and raised such commercial commodities as grain, livestock, and dairy product. A second farm in the county that was operated by John Sims encompassed 337 acres and raised a variety of crops, including corn, oats, tobacco, cotton, and butter.[10]

The Black Walnut plantation complex grew to encompass a variety of domestic and agricultural outbuildings; the main house served as the focal point. Domestic outbuildings, including a smokehouse, dairy, kitchen, and icehouse, were placed in a U-shaped cluster to the rear, or west, of the main house. Slave quarters and agricultural outbuildings were more isolated from the main living area. A formal boxwood garden was laid out south of the main house, and a terraced vegetable garden was situated to the northwest. A variety of native and ornamental trees and shrubs landscaped the grounds, and the entire complex was enclosed by woodland. A family cemetery was situated northwest of the house.[2]

John Sims' prosperity was illustrated by the substantial modifications made to the manor house during the first quarter of the nineteenth century, at which time the central section of the house was raised to a full two-story height. The house was altered again with the construction of a substantial two-story frame addition connected by a central hyphen, resulting in its present H-shaped configuration. The 1848 tax assessment for this property shows an increase in valuation due to "improvements". The plan of the house consisted of two center-hall, single-pile units joined by a center hyphen. The exterior walls were sheathed in beaded wood siding. The building's massing terminated in a gable roof sheathed in metal standing-seam panels. Wooden block modillions ornamented the front and rear eaves and partially returned cornices. Central brick exterior-end chimneys were located on each gable-end. Small attic vents punctuated the gable ends. The three-bay main facade was characterized by its symmetrical composition. A one-story hipped roof portico was centered on the facade and delineated the front entrance. Nine-over-nine-light, double-hung, wooden sash windows were aligned across this facade. The window openings were framed by louvered wood blinds. One-room units flanked the rear two-story section, and a one-story porch extended across the rear elevation.[2]

Only a few of the plantation's outbuildings are extant from this period of development, and include a wash house/cool storage, a smokehouse, a slave cabin, a corn house, and a two-room brick kitchen situated directly behind the main house. All of these buildings were constructed of wood-frame and terminated in steeply-pitched gable roofs.

Two tobacco barns and another slave quarter still survive and are situated southeast of the main house. These outbuildings were isolated from the main domestic complex and were characterized by their log construction. As of 1996, all of these buildings existed in a ruinous state.

William Howson Sims (1852-1890)

At the time of John Sims' death in 1852, the estate had increased substantially in value and grown to encompass roughly 2,500 acres. Other real estate included 245 sheep, 12 oxen, 300 hogs, and 100 head of cattle. John Sims bequeathed the majority of his real estate, including the mansion house, to his son, William Howson Sims. Smaller landholdings were distributed between Maria Garrett, his only surviving daughter, and his grandchildren. Maria Garrett received 47 slaves and small properties, while his granddaughter, Elizabeth Coleman, daughter of Mary Elizabeth, received 46 slaves.[10]

William Howson Sims managed the substantial Black Walnut plantation between 1852 until his death in 1890. William Howson was educated at Hampden-Sydney and passed the bar. "However, innovative farming techniques were more attractive to him than the practice of law, and his time was devoted to the running of his plantation". During his tenure, he acquired title to the additional portions of the Black Walnut tract, as well as purchasing other landholdings in Halifax County. William Howson also assisted his aunt, Phoebe Howson Clark Bailey, with the operation of her plantation, "Oak Hill". According to correspondence on file in the Bailey Family Papers, Phoebe Bailey's nephew, W.H. Sims, would mount his horse and spent the night at her plantation to assist her with affairs.

In 1844, prior to inheriting the Black Walnut property, William Howson brought his wife, Sallie J. Wilson, and their four children, Eliza Broadnax, Maria Clark, John, and William Bailey, to reside at the manor house. During the 1860s, both of his daughters were sent to Richmond to attend private school. John Sims attended Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in 1867, while William Bailey was educated at "Creek Side". William S. later graduated from Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Virginia.

In 1857, roughly 22 acres were sold to the Richmond and Danville Railroad Company. By this period, William Howson Sims owned 16 tracts of land in Halifax County, along with 116 slaves. He employed four overseers to manage his extensive landholdings. The 1860 Census identifies William Howson Sims as a "planter" owning $57,000.00 worth of real estate and $238,270.00 worth of personal property.[10]

The Civil War

With the commencement of the Civil War, William H. Sims did not join the Confederate army and, instead, continued to operate his plantation. It is likely that William Sims concurred with the general opinion that the war would be short and successful because as the war progressed, Sims' efforts for the Confederate cause increased. In March 1862, Sims was conscripted and was slated to serve as a private in Captain Moore's Company of the 84th Virginia Infantry. William appealed his case to the Halifax County Conscription Exemption Board and was allowed to hire a substitute. Sims was required to pay $30.00 to provide his substitute with a uniform. Sims wrote to his uncle about the news. In the same letter, he also noted that Governor Letcher had mobilized the Richmond militia to fight. At that time Union troops were landing at Fort Monroe in Hampton Roads to begin a march upon Richmond. Sims was conscripted again the following year and was exempted. Joseph H. Lambeth served as his substitute.

After the Confederate government ceased the practice of substitution, William Sims applied for an exemption. While approval of his exemption was pending, he prepared to join the army as part of the Black Walnut Cavalry Company. Sims did not join the cavalry company but, instead, remained at Black Walnut.

In June 1864, the Battle of Staunton River Bridge took place. The Union objective was the destruction of the R&D railroad bridge over the Staunton River. Confederate forces prepared defenses on the Sims' side of the river, and on the eastern bank. Following the battle, a permanent Confederate garrison was established on Sims' property that was manned by both troops and 800 slave laborers.

William Sims was conscripted again in August 1864, at which time he was officially assigned to the Danville Division of the Confederate Subsistence Department, under the command of Col. A. H. McCleish. His duty was to collect foodstuffs in the Halifax region and forward them to the army.

According to the 1860 Agricultural Census, William Howson Sims had 1,800 acres under cultivation and 2,000 unimproved acres. During the Civil War, William Howson responded to the state's dire food shortages by practicing agricultural diversification, harvesting crops such as tobacco, wheat, Indian corn, oats, peas and beans, potatoes, grass seed, and hops. Horses, cows, oxen, sheep, and pigs also were raised on the plantation. Other products included 260 pounds of wool, 300 pounds of butter, and three pounds of beeswax.[10]

Throughout 1863, Sims continued to transport agricultural goods to the Clover Depot of the Richmond and Danville (R&D) Railroad. By the following year, William Howson was forced to discontinue shipping agricultural goods from the Clover Depot due to a lack of available railroad cars for storage or transport. William Howson also lost several of his male slaves after they were requisitioned by the Confederate army. In October, Sims' overseers were also conscripted.

To exacerbate the situation, the region experienced a drought during the summer of 1864. Sims' efforts to purchase wheat for the army met with little success. In October, Sims collected 14 bushels and 25 pounds of wheat for the Quartermaster Department. In November 1864 Sims provided the Army Quartermaster with 1,948 pounds of baled oats; 2,093 pounds of fodder; and 1,242 pounds of corn. On March 9, 1865, he provided 11,284 pounds of straw.

Sims also sold beef to the Confederate troops and slave laborers stationed at the garrison. Sims signed a pardon on August 2, 1865. Union troops continued to occupy the Black Walnut Plantation following the conclusion of the war, however, this did not halt commercial activity. On April 17, 1865, Sims sold 1,500 pounds of oats, one barrel of flour, and three and one-half barrels of corn.

Reconstruction - Present

Following the Civil War, William H. Sims reduced his landholdings. By 1870, the amount of acreage under cultivation dropped to 225 acres, with 1,000 unimproved acres. William H. most likely rented land to tenant farmers; in addition, many of the former slaves continued to live on the plantation, serving either as tenant farmers or paid laborers. Tobacco continued as the primary cash crop during this period. Although tobacco production was less than half of the amount produced during the previous decade, William Howson remained one of the top five tobacco producers in the Roanoke District. Other agricultural crops included wheat, corn, and oats. A variety of livestock was raised during this period, including horses, mules, oxen, cattle, sheep, and pigs.[2]

By 1880, William H. had 245 acres of tilled land, 150 acres of meadow and pasture, and 1,000 acres of wooded land. His livestock was reduced slightly to include seven horses, four mules, seven oxen, 40 sheep, and 35 pigs. Agricultural products were diverse and included eggs, butter, honey, and fruit. For the next 98 years, the heirs of William H. continued to operate various sections of the plantation. In 1978, Dr. William Randolph Watkins, grandson of Maria Sims Garrett, took over ownership of the property.[2] Upon his death in 1997, his son Tucker Carrington Watkins IV occupied the plantation and made various improvements. After Tucker died on 6 October 2012, his nephew John Payne Thrift III decided to auction off the contents of the house and sell the 775-acre (314-hectare) property for $2,050,000 in 2014, as no-one in the family had an interest in living there. This marked the first time the house had been on the market since 1768.[11][12]

References

- "Virginia Landmarks Register 041-0006". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Pierce, Diane (June 1991). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: 041-0006 Black Walnut" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-09. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- McLaughlin, Tom (20 June 2014). "War Comes to the Plantation". www.SoVaNow.com. The News & Record. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- Edmunds, Pocahontas (1978). History of Halifax (1st ed.). pp. 69–71.

- Watts, Jakon Hays, Maureen (10 September 2017). "September 1939 | Mary Pickford makes a visit". pilotonline.com. Retrieved 2021-01-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Staunton River Battlefield". Longwood University. Summer 2013. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Chiarito, Marian D. (1983). Vestry Book of Antrim Parish, Halifax County, Virginia, 1752-1817. Wildside Press. ISBN 9780809582518.

- T.L.C. Genealogy. 1991. p. 6.

- Gilliam and McKinney (Volume VI No. 3 ed.). 1993. pp. 55–56.

- Kuranda, Kathryn M. (2003). "Black Walnut Monograph". OldHalifax.com. R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc. (published 1996). Archived from the original on 2004-11-06. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- "Tucker Watkins, GOP activist, dies at 66". www.SoVaNow.com. The News & Record. 6 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 7 Jan 2021.

- Watson, Denise (15 October 2014). "On the auction block: Historic Black Walnut plantation". pilotonline.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-10. Retrieved 7 Jan 2021.