Black and red ware

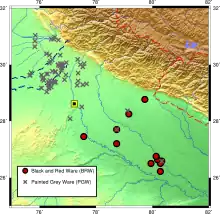

Black and red ware (BRW) is a South Asian earthenware, associated with the neolithic phase, Harappa, Bronze Age India, Iron Age India, the megalithic and the early historical period.[1] Although it is sometimes called an archaeological culture, the spread in space and time and the differences in style and make are such that the ware must have been made by several cultures.[2]

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

In the Western Ganges plain (western Uttar Pradesh) it is dated to c. 1450–1200 BCE, and is succeeded by the Painted Grey Ware culture; whereas in the Central and Eastern Ganges plain (eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Bengal) and Central India (Madhya Pradesh) the BRW appears during the same period but continues for longer, until c. 700–500 BCE, when it is succeeded by the Northern Black Polished Ware culture.[3]

In the Western Ganges plain, the BRW was preceded by the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture. The BRW sites were characterized by subsistence agriculture (cultivation of rice, barley, and legumes), and yielded some ornaments made of shell, copper, carnelian, and terracotta.[4]

In some sites, particularly in eastern Punjab and Gujarat, BRW pottery is associated with Late Harappan pottery, and according to some scholars like Tribhuan N. Roy, the BRW may have directly influenced the Painted Grey Ware and Northern Black Polished Ware cultures.[5] BRW pottery is unknown west of the Indus Valley.[6]

Use of iron, although sparse at first, is relatively early, postdating the beginning of the Iron Age in Anatolia (Hittites) by only two or three centuries, and predating the European (Celts) Iron Age by another two to three hundred years. Recent findings in Northern India show Iron working in the 1800–1000 BCE period.[7] According to Shaffer, "the nature and context of the iron objects involved are very different from early iron objects found in Southwest Asia."[8] From Sri Lanka, a variant of Black and red Ware has been discovered from its early iron age (900–600 BCE) which is also marked by appearance of horses, paddy fields, iron tools etc.[9]

See also

- Kuru Kingdom

- Malwa culture

- Jorwe culture

- Rang Mahal culture, Rajasthan-Haryana border

- Pottery in the Indian subcontinent

- Vedic period

Notes

- Shaffer, Jim. Mathura: A protohistoric Perspective in D.M. Srinivasan (ed.), Mathura, the Cultural Heritage, 1989, pp. 171–180. Delhi.

References

- Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Jaffna. p. 9.

- Singh (1979)

- Franklin Southworth, Linguistic Archaeology of South Asia (Routledge, 2005), p. 177

- Upinder Singh (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, p.220

- Shaffer, Jim. 1993, Reurbanization: The eastern Punjab and beyond. In Urban Form and Meaning in South Asia: The Shaping of Cities from Prehistoric to Precolonial Times, ed. H. Spodek and D.M. Srinivasan. p. 57

- Shaffer, Jim. Mathura: A protohistoric Perspective in D.M. Srinivasan (ed.), Mathura, the Cultural Heritage, 1989, pp. 171–180. Delhi. cited in Chakrabarti 1992

- Tewari, Rakesh (2003). "The origins of iron working in India: new evidence from the Central Ganga Plain and the Eastern Vindhyas" (PDF). Antiquity. 77 (297): 536–544. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.4300. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00092590.

- Shaffer 1989, cited in Chakrabarti 1992:171

- Wikramanayake, T. W. (2004). "THE LIFE STYLE OF EARLY INHABITANTS OF SRI LANKA". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka. 50: 89–140. ISSN 1391-720X.

External links

- Singh, H.N. (1979): 'Black and Red Ware. A Cultural Study' in Agrawal, D.P.; Chakrabarti, D.K. (ed.) Essays in Indian Protohistory, B.R. Publishing Corporation

- The origins of iron-working in India: new evidence from the Central Ganga Plain and the Eastern Vindhyas by Rakesh Tewari

- India Heritage – Earthenware and Pottery