Linguistic history of India

Since the Iron Age in India, the native languages of the Indian subcontinent are divided into various language families, of which the Indo-Aryan and the Dravidian are the most widely spoken. There are also many languages belonging to unrelated language families such as Munda (from Austroasiatic family) and Tibeto-Burman (from Trans-Himalayan family), spoken by smaller groups.

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

Indo-Aryan languages

Proto-Indo-Aryan

Proto-Indo-Aryan is a proto-language hypothesized to have been the direct ancestor of all Indo-Aryan languages.[1] It would have had similarities to Proto-Indo-Iranian, but would ultimately have used Sanskritized phonemes and morphemes.

Vedic Sanskrit

Vedic Sanskrit is the language of the Vedas, a large collection of hymns, incantations, and religio-philosophical discussions which form the earliest religious texts in India and the basis for much of the Hindu religion. Modern linguists consider the metrical hymns of the Rigveda to be the earliest. The hymns preserved in the Rigveda were preserved by oral tradition alone over several centuries before the introduction of writing, the oldest Aryan language among them predating the introduction of Brahmi by as much as a millennium.

The end of the Vedic period is marked by the composition of the Upanishads, which form the concluding part of the Vedic corpus in the traditional compilations, dated to roughly 500 BCE. It is around this time that Sanskrit began the transition from a first language to a second language of religion and learning, marking the beginning of Classical India.

Classical Sanskrit

The oldest language surviving Sanskrit grammar is patanjali's Aṣṭādhyāyī ("Eight-Chapter Grammar") dating to c. the 5th century BCE. It is essentially a prescriptive grammar, i.e., an authority that defines (rather than describes) correct Sanskrit, although it contains descriptive parts, mostly to account for Vedic forms that had already passed out of use in Pāṇini's time.

Knowledge of Sanskrit was a marker of social class and educational attainment.

Vedic Sanskrit and Classical or "Paninian" Sanskrit, while broadly similar, are separate[2] varieties, which differ in a number of points of phonology, vocabulary, and grammar.

Prakrits

Prakrit (Sanskrit prākṛta प्राकृत, the past participle of प्राकृ, meaning "original, natural, artless, normal, ordinary, usual", i.e. "vernacular", in contrast to samskrta "excellently made", both adjectives elliptically referring to vak "speech") is the broad family of Indo-Aryan languages and dialects spoken in ancient India. Some modern scholars include all Middle Indo-Aryan languages under the rubric of "Prakrits", while others emphasise the independent development of these languages, often separated from the history of Sanskrit by wide divisions of caste, religion, and geography.

The Prakrits became literary languages, generally patronized by kings identified with the kshatriya caste. The earliest inscriptions in Prakrit are those of Ashoka, emperor of the Maurya Empire, and while the various Prakrit languages are associated with different patron dynasties, with different religions and different literary traditions.

In Sanskrit drama, kings speak in Prakrit when addressing women or servants, in contrast to the Sanskrit used in reciting more formal poetic monologues.

The three Dramatic Prakrits – Sauraseni, Magadhi, Maharashtri, as well as Jain Prakrit each represent a distinct tradition of literature within the history of India. Other Prakrits are reported in historical sources, but have no extant corpus (e.g., Paisaci).

Pali

Pali is the Middle Indo-Aryan language in which the Theravada Buddhist scriptures and commentaries are preserved. Pali is believed by the Theravada tradition to be the same language as Magadhi, but modern scholars believe this to be unlikely. Pali shows signs of development from several underlying Prakrits as well as some Sanskritisation.

The Prakrit of the North-western area of India known as Gāndhāra has come to be called Gāndhārī. A few documents are written in the Kharoṣṭhi script survive including a version of the Dhammapada.

Apabhraṃśa/Apasabda

The Prakrits (which includes Pali) were gradually transformed into Apabhraṃśas (अपभ्रंश) which were used until about the 13th century CE. The term apabhraṃśa, meaning "fallen away", refers to the dialects of Northern India before the rise of modern Northern Indian languages, and implies a corrupt or non-standard language. A significant amount of apabhraṃśa literature has been found in Jain libraries. While Amir Khusro and Kabir were writing in a language quite similar to modern Hindi-Urdu, many poets, especially in regions that were still ruled by Hindu kings, continued to write in Apabhraṃśa. Apabhraṃśa authors include Sarahapad of Kamarupa, Devasena of Dhar (9th century CE), Pushpadanta of Manikhet (9th century CE), Dhanapal, Muni Ramsimha, Hemachandra of Patan, Raighu of Gwalior (15th century CE). An early example of the use of Apabhraṃśa is in Vikramōrvaśīyam of Kalidasa, when Pururava asks the animals in the forest about his beloved who had disappeared.

Hindustani

Hindustani is right now the most spoken language in the Indian subcontinent and the fourth most spoken language in the world. The development of Hindustani revolves around the various Hindi dialects originating mainly from Sauraseni Apabhramsha. A Jain text Shravakachar written in 933AD is considered the first Hindi book.[3] Modern Hindi is based on the prestigious Khariboli dialect which started to take Persian and Arabic words too with the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate; however, the Arabic-Persian influence was profound mainly on Urdu and to a lesser extent on Hindi.Khadiboli also started to spread across North India as a vernacular form previously commonly known as Hindustani. Amir Khusrow wrote poems in Khariboli and Brajbhasha and referred that language as Hindavi. During the Bhakti era, many poems were composed in Khariboli, Brajbhasa, and Awadhi. One such classic is Ramcharitmanas, written by Tulsidas in Awadhi. In 1623 Jatmal wrote a book in Khariboli with the name 'Gora Badal ki Katha'.

The establishment of British rule in the subcontinent saw the clear division of Hindi and Urdu registers. This period also saw the rise of modern Hindi literature starting with Bharatendu Harishchandra. This period also shows further Sanskritization of the Hindi language in literature. Hindi is right now the official language in nine states of India— Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh—and the National Capital Territory of Delhi. Post-independence Hindi became the official language of the Central Government of India along with English. Urdu has been the national and official language of Pakistan as well as the lingua franca of the country.

Outside the India, Hindustani is widely understood in other parts of the Indian subcontinent and also used as a lingua franca, and is the main language of Bollywood.

Marathi

Marathi is one of several languages that further descend from Maharashtri Prakrit. Further change led to the Apabhraṃśa languages like Old Marathi, however, this is challenged by Bloch (1970), who states that Apabhraṃśa was formed after Marathi had already separated from the Middle Indian dialect.[4] The earliest example of Maharashtri as a separate language dates to approximately 3rd century BCE: a stone inscription found in a cave at Naneghat, Junnar in Pune district had been written in Maharashtri using Brahmi script. A committee appointed by the Maharashtra State Government to get the Classical status for Marathi has claimed that Marathi existed at least 2300 years ago alongside Sanskrit as a sister language.[5] Marathi, a derivative of Maharashtri, is probably first attested in a 739 CE copper-plate inscription found in Satara After 1187 CE, the use of Marathi grew substantially in the inscriptions of the Seuna (Yadava) kings, who earlier used Kannada and Sanskrit in their inscriptions.[6] Marathi became the dominant language of epigraphy during the last half century of the dynasty's rule (14th century), and may have been a result of the Yadava attempts to connect with their Marathi-speaking subjects and to distinguish themselves from the Kannada-speaking Hoysalas.[7][8]

Marathi gained prominence with the rise of the Maratha Empire beginning with the reign of Shivaji (1630–1680). Under him, the language used in administrative documents became less persianised. Whereas in 1630, 80% of the vocabulary was Persian, it dropped to 37% by 1677[9] The British colonial period starting in early 1800s saw standardisation of Marathi grammar through the efforts of the Christian missionary William Carey. Carey's dictionary had fewer entries and Marathi words were in Devanagari. Translations of the Bible were first books to be printed in Marathi. These translations by William Carey, the American Marathi mission and the Scottish missionaries led to the development of a peculiar pidginized Marathi called "Missionary Marathi” in the early 1800s.[10]

After Indian independence, Marathi was accorded the status of a scheduled language on the national level. In 1956, the then Bombay state was reorganized which brought most Marathi and Gujarati speaking areas under one state. Further re-organization of the Bombay state on 1 May 1960, created the Marathi speaking Maharashtra and Gujarati speaking Gujarat state respectively. With state and cultural protection, Marathi made great strides by the 1990s.

Dravidian languages

| Proto-Dravidian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-South-Dravidian | Proto-South-Central Dravidian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil-Kannada | Proto-Telugu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil-Toda | Proto-Kannada | Proto-Telugu | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil-Kodagu | Kannada | Telugu | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil-Malayalam | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil | Malayalam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tamil | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Dravidian family of languages includes approximately 73 languages[11] that are mainly spoken in southern India and northeastern Sri Lanka, as well as certain areas in Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and eastern and central India, as well as in parts of southern Afghanistan, and overseas in other countries such as the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Malaysia and Singapore.

The origins of the Dravidian languages, as well as their subsequent development and the period of their differentiation, are unclear, and the situation is not helped by the lack of comparative linguistic research into the Dravidian languages. Many linguists, however, tend to favor the theory that speakers of Dravidian languages spread southwards and eastwards through the Indian subcontinent, based on the fact that the southern Dravidian languages show some signs of contact with linguistic groups which the northern Dravidian languages do not. Proto-Dravidian is thought to have differentiated into Proto-North Dravidian, Proto-Central Dravidian and Proto-South Dravidian around 1500 BCE, although some linguists have argued that the degree of differentiation between the sub-families points to an earlier split.

It was not until 1856 that Robert Caldwell published his Comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages, which considerably expanded the Dravidian umbrella and established it as one of the major language groups of the world. Caldwell coined the term "Dravidian" from the Sanskrit drāvida, related to the word 'Tamil' or 'Tamilan', which is seen in such forms as into 'Dramila', 'Drami˜a', 'Dramida' and 'Dravida' which was used in a 7th-century text to refer to the languages of the southern India. The Dravidian Etymological Dictionary was published by T. Burrow and M. B. Emeneau.

History of Tamil

Linguistic reconstruction suggests that Proto-Dravidian was spoken around the 6th millennium BCE. The material evidence suggests that the speakers of Proto-Dravidian were the culture associated with the Neolithic complexes of South India.[12] The next phase in the reconstructed proto-history of Tamil is Proto-South Dravidian. The linguistic evidence suggests that Proto-South Dravidian was spoken around the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE and Old Tamil emerged around the 6th century BCE. The earliest epigraphic attestations of Tamil are generally taken to have been written shortly thereafter.[13] Among Indian languages, Tamil has one of the ancient Indian literature besides others.[14]

Scholars categorise the attested history of the language into three periods, Old Tamil (400 BCE – 700 CE), Middle Tamil (700–1600) and Modern Tamil (1600–present).[15]

Old Tamil

The earliest records in Old Tamil are short inscriptions from around the 6th century BCE in caves and on pottery. These inscriptions are written in a variant of the Brahmi script called Tamil Brahmi.[16] The earliest long text in Old Tamil is the Tolkāppiyam, an early work on Tamil grammar and poetics, whose oldest layers could be as old as the 2nd century BCE.[15] A large number of literary works in Old Tamil have also survived. These include a corpus of 2,381 poems collectively known as Sangam literature. These poems are usually dated to between the 1st and 5th centuries CE,[17] which makes them the oldest extant body of secular literature in India.[18] Other literary works in Old Tamil include two long epics, Cilappatikaram and Manimekalai, and a number of ethical and didactic texts, written between the 5th and 8th centuries.[19]

Old Tamil preserved some features of Proto-Dravidian, including the inventory of consonants,[20] the syllable structure,[21] and various grammatical features.[22] Amongst these was the absence of a distinct present tense – like Proto-Dravidian, Old Tamil only had two tenses, the past and the "non-past". Old Tamil verbs also had a distinct negative conjugation (e.g. kāṇēṉ (காணேன்) "I do not see", kāṇōm (காணோம்) "we do not see").[23] Nouns could take pronominal suffixes like verbs to express ideas: e.g. peṇṭirēm (பெண்டிரேம்) "we are women" formed from peṇṭir (பெண்டிர்) "women" + -ēm (ஏம்) and the first person plural marker.[24]

Despite the significant amount of grammatical and syntactical change between Old, Middle and Modern Tamil, Tamil demonstrates grammatical continuity across these stages: many characteristics of the later stages of the language have their roots in features of Old Tamil.[15]

Middle Tamil

The evolution of Old Tamil into Middle Tamil, which is generally taken to have been completed by the 8th century,[15] was characterised by a number of phonological and grammatical changes. In phonological terms, the most important shifts were the virtual disappearance of the aytam (ஃ), an old phoneme,[25] the coalescence of the alveolar and dental nasals,[26] and the transformation of the alveolar plosive into a rhotic.[27] In grammar, the most important change was the emergence of the present tense. The present tense evolved out of the verb kil (கில்), meaning "to be possible" or "to befall". In Old Tamil, this verb was used as an aspect marker to indicate that an action was micro-durative, non-sustained or non-lasting, usually in combination with a time marker such as ṉ (ன்). In Middle Tamil, this usage evolved into a present tense marker – kiṉṟ (கின்ற) – which combined the old aspect and time markers.[28]

Middle Tamil also saw a significant increase in the Sanskritisation of Tamil. From the period of the Pallava dynasty onwards, a number of Sanskrit loan-words entered Tamil, particularly in relation to political, religious and philosophical concepts.[29] Sanskrit also influenced Tamil grammar, in the increased use of cases and in declined nouns becoming adjuncts of verbs,[30] and phonology.[31] The Tamil script also changed in the period of Middle Tamil. Tamil Brahmi and Vaṭṭeḻuttu, into which it evolved, were the main scripts used in Old Tamil inscriptions. From the 8th century onwards, however, the Pallavas began using a new script, derived from the Pallava Grantha script which was used to write Sanskrit, which eventually replaced Vaṭṭeḻuttu.[32]

Middle Tamil is attested in a large number of inscriptions, and in a significant body of secular and religious literature.[33] These include the religious poems and songs of the Bhakthi poets, such as the Tēvāram verses on Saivism and Nālāyira Tivya Pirapantam on Vaishnavism,[34] and adaptations of religious legends such as the 12th-century Tamil Ramayana composed by Kamban and the story of 63 shaivite devotees known as Periyapurāṇam.[35] Iraiyaṉār Akapporuḷ, an early treatise on love poetics, and Naṉṉūl, a 12th-century grammar that became the standard grammar of literary Tamil, are also from the Middle Tamil period.[36]

Modern Tamil

The Nannul remains the standard normative grammar for modern literary Tamil, which therefore continues to be based on Middle Tamil of the 13th century rather than on Modern Tamil.[37] Colloquial spoken Tamil, in contrast, shows a number of changes. The negative conjugation of verbs, for example, has fallen out of use in Modern Tamil[38] – negation is, instead, expressed either morphologically or syntactically.[39] Modern spoken Tamil also shows a number of sound changes, in particular, a tendency to lower high vowels in initial and medial positions,[40] and the disappearance of vowels between plosives and between a plosive and rhotic.[41]

Contact with European languages also affected both written and spoken Tamil. Changes in written Tamil include the use of European-style punctuation and the use of consonant clusters that were not permitted in Middle Tamil. The syntax of written Tamil has also changed, with the introduction of new aspectual auxiliaries and more complex sentence structures, and with the emergence of a more rigid word order that resembles the syntactic argument structure of English.[42] Simultaneously, a strong strain of linguistic purism emerged in the early 20th century, culminating in the Pure Tamil Movement which called for removal of all Sanskritic and other foreign elements from Tamil.[43] It received some support from Dravidian parties and nationalists who supported Tamil independence.[44] This led to the replacement of a significant number of Sanskrit loanwords by Tamil equivalents, though many others remain.[45]

Literature

Tamil literature has a rich and long literary tradition spanning more than two thousand years. The oldest extant works show signs of maturity indicating an even longer period of evolution. Contributors to the Tamil literature are mainly from Tamil people from Tamil Nadu, Sri Lankan Tamils from Sri Lanka, and from Tamil diaspora. Also, there have been notable contributions from European authors. The history of Tamil literature follows the history of Tamil Nadu, closely following the social and political trends of various periods. The secular nature of the early Sangam poetry gave way to works of religious and didactic nature during the Middle Ages. Jain and Buddhist authors during the medieval period and Muslim and European authors later, contributed to the growth of Tamil literature.

A revival of Tamil literature took place from the late 19th century when works of religious and philosophical nature were written in a style that made it easier for the common people to enjoy. Nationalist poets began to utilize the power of poetry in influencing the masses. With the growth of literacy, Tamil prose began to blossom and mature. Short stories and novels began to appear. The popularity of Tamil Cinema has also provided opportunities for modern Tamil poets to emerge.

History of Kannada

Kannada is one of oldest languages in South India.[46][47][48][49] The spoken language is said to have separated from its proto-language source earlier than Tamil and about the same time as Tulu.[50] However, archaeological evidence would indicate a written tradition for this language of around 1600–1650 years. The initial development of the Kannada language is similar to that of other south Indian languages.[51][52]

Stages of development

By the time Halmidi shasana (stone inscription) Kannada had become an official language. Some of the linguistics suggest that Tamil & HaLegannada are very similar or might have same roots. Ex: For milk in both languages it is 'Haalu', the postfix to the names of elders to show respect is 'avar / avargaL'.

600 – 1200 AD

During this era, language underwent a lot of changes as seen from the literary works of great poets of the era viz Pampa, Ranna, Ponna.

1400 – 1600 AD

Vijayanagar Empire which is called the Golden era in the history of medieval India saw a lot of development in all literary form of both Kannada and Telugu. During the ruling of the King Krishnadevaraya many wonderful works. Poet Kumaravyasa wrote Mahabharata in Kannada in a unique style called "shatpadi" (six lines is a stanza of the poem). This era also saw the origin of Dasa Sahitya, the Carnatic music. Purandaradasa and Kanakadasa wrote several songs praising Lord Krishna. This gave a new dimension to Kannada literature.

Stone inscriptions

The first written record in the Kannada language is traced to Emperor Ashoka's Brahmagiri edict dated 200 BCE.[53][54] The first example of a full-length Kannada language stone inscription (shilashaasana) containing Brahmi characters with characteristics attributed to those of protokannada in Hale Kannada (Old Kannada) script can be found in the Halmidi inscription, dated c. 450, indicating that Kannada had become an administrative language by this time.[55][56][57] Over 30,000 inscriptions written in the Kannada language have been discovered so far.[58] The Chikkamagaluru inscription of 500 CE is another example.[59][60] Prior to the Halmidi inscription, there is an abundance of inscriptions containing Kannada words, phrases and sentences, proving its antiquity. Badami cliff shilashaasana of Pulakeshin I is an example of a Sanskrit inscription in Hale Kannada script.[61][62]

Copper plates and manuscripts

Examples of early Sanskrit-Kannada bilingual copper plate inscriptions (tamarashaasana) are the Tumbula inscriptions of the Western Ganga Dynasty dated 444 AD[63][64] The earliest full-length Kannada tamarashaasana in Old Kannada script (early 8th century) belongs to Alupa King Aluvarasa II from Belmannu, South Kanara district and displays the double crested fish, his royal emblem.[65] The oldest well-preserved palm leaf manuscript is in Old Kannada and is that of Dhavala, dated to around the 9th century, preserved in the Jain Bhandar, Mudbidri, Dakshina Kannada district.[66] The manuscript contains 1478 leaves written in ink.[66]

Origins

Telugu is hypothesised to have originated from a reconstructed Proto-Dravidian language. It is a highly Sanskritised language; as Telugu scholar C.P Brown states in page 266 of his book A Grammar of the Telugu language: "if we ever make any real progress in the language the student will require the aid of the Sanskrit Dictionary".[67] Prakrit Inscriptions containing Telugu words dated around 400–100 BCE were discovered in Bhattiprolu in District of Guntur. English translation of one inscription as reads: "Gift of the slab by venerable Midikilayakha".[68]

Stages

From 575 CE, we begin to find traces of Telugu in inscriptions and literature, it is possible to broadly define four stages in the linguistic history of the Telugu language:

575 –1100

The first inscription that is entirely in Telugu corresponds to the second phase of Telugu history. This inscription, dated 575, was found in the districts of Kadapa and Kurnool and is attributed to the Renati Cholas, who broke with the prevailing practice of using Prakrit and began writing royal proclamations in the local language. During the next fifty years, Telugu inscriptions appeared in Anantapuram and other neighboring regions. The earliest dated Telugu inscription from coastal Andhra Pradesh comes from about 633 .

Around the same time, the Chalukya kings of Telangana also began using Telugu for inscriptions. Telugu was more influenced by Sanskrit than Prakrit during this period, which corresponded to the advent of Telugu literature. One of the oldest Telugu stone inscriptions containing literature was the 11-line inscription dated between 946 and 968 found on a hillock known as Bommalagutta in Kurikyala village of Karimnagar district, Telangana. The sing-song Telugu rhyme was the work of Jinavallabha, the younger brother of Pampa who was the court poet of Vemulavada Chalukya king Arikesari III.[69] This literature was initially found in inscriptions and poetry in the courts of the rulers, and later in written works such as Nannayya's Mahabharatam (1022 ). During the time of Nannayya, the literary language diverged from the popular language. This was also a period of phonetic changes in the spoken language.

1100 – 1400

The third phase is marked by further stylization and sophistication of the literary language. Ketana (13th century CE) in fact prohibited the use of the vernacular in poetic works. During this period the divergence of the Telugu script from the common Telugu-Kannada script took place.[70] Tikkana wrote his works in this script.

1400–1900

Telugu underwent a great deal of change (as did other Indian languages), progressing from medieval to modern. The language of the Telangana region started to split into a distinct dialect due to Muslim influence: Sultanate rule under the Tughlaq dynasty had been established earlier in the northern Deccan during the 14th century CE. South of the Krishna River (in the Rayalaseema region), however, the Vijayanagara Empire gained dominance from 1336 CE until the late 17th century, reaching its peak during the rule of Krishnadevaraya in the 16th century, when Telugu literature experienced what is considered to be its golden age.[71] Padakavithapithamaha, Annamayya, contributed many atcha (pristine) Telugu Padaalu to this great language. In the latter half of the 17th century, Muslim rule extended further south, culminating in the establishment of the princely state of Hyderabad by the Asaf Jah dynasty in 1724 CE. This heralded an era of Persian/Arabic influence on the Telugu language, especially on that spoken by the inhabitants of Hyderabad. The effect is also felt in the prose of the early 19th century, as in the Kaifiyats.[71]

1900 to date

The period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the influence of the English language and modern communication/printing press as an effect of the British rule, especially in the areas that were part of the Madras Presidency. Literature from this time had a mix of classical and modern traditions and included works by scholars like Kandukuri Viresalingam, Gurazada Apparao, and Panuganti Lakshminarasimha Rao.[71]

Since the 1930s, what was considered an elite literary form of the Telugu language has now spread to the common people with the introduction of mass media like movies, television, radio and newspapers. This form of the language is also taught in schools as a standard. In the current decade the Telugu language, like other Indian languages, has undergone globalization due to the increasing settlement of Telugu-speaking people abroad. Modern Telugu movies, although still retaining their dramatic quality, are linguistically separate from post-Independence films.

At present, a committee of scholars have approved a classical language tag for Telugu based on its antiquity. The Indian government has also officially designated it as a classical language.[72]

Carnatic music

Though Carnatic music, one of two main subgenres of Indian classical music that evolved from ancient Hindu traditions, has a profound cultural influence on all of the South Indian states and their respective languages, most songs (Kirtanas) are in Kannada and Telugu. Purandara Dasa, said to have composed at least a quarter million songs and known as the "father" of Carnatic music composed in Kannada.

The region to the east of Tamil Nadu stretching from Tanjore in the south to Andhra Pradesh in the north was known as the Carnatic region during 17th and 18th centuries. The Carnatic war in which Robert Clive annexed Trichirapali is relevant. The music that prevailed in this region during the 18th century onwards was known as Carnatic music. This is because the existing tradition is to a great extent an outgrowth of the musical life of the principality of Thanjavur in the Kaveri delta. Thanjavur was the heart of the Chola dynasty (from the 9th century to the 13th), but in the second quarter of the 16th century a Telugu Nayak viceroy (Raghunatha Nayaka) was appointed by the emperor of Vijayanagara, thus establishing a court whose language was Telugu. The Nayaks acted as governors of what is present-day Tamil Nadu with their headquarters at Thanjavur (1530–1674 CE) and Madurai(1530–1781 CE). After the collapse of Vijayanagar, Thanjavur and Madurai Nayaks became independent and ruled for the next 150 years until they were replaced by Marathas. This was the period when several Telugu families migrated from Andhra and settled down in Thanjavur and Madurai. Most great composers of Carnatic music belonged to these Telugu families.

Telugu words end in vowels which many consider a mellifluous quality and thus suitable for musical expression. Of the trinity of Carnatic music composers, Tyagaraja's and Syama Sastri's compositions were largely in Telugu, while Muttuswami Dikshitar is noted for his Sanskrit texts. Tyagaraja is remembered both for his devotion and the bhava of his krithi, a song form consisting of pallavi, (the first section of a song) anupallavi (a rhyming section that follows the pallavi) and charanam (a sung stanza which serves as a refrain for several passages in the composition). The texts of his kritis are almost all in Sanskrit, in Telugu (the contemporary language of the court). This use of a living language, as opposed to Sanskrit, the language of ritual, is in keeping with the bhakti ideal of the immediacy of devotion. Sri Syama Sastri, the oldest of the trinity, was taught Telugu and Sanskrit by his father, who was the pujari (Hindu priest) at the Meenakshi temple in Madurai. Syama Sastri's texts were largely composed in Telugu, widening their popular appeal. Some of his most famous compositions include the nine krithis, Navaratnamaalikā, in praise of the goddess Meenakshi at Madurai, and his eighteen krithi in praise of Kamakshi. As well as composing krithi, he is credited with turning the svarajati, originally used for dance, into a purely musical form.

History of Malayalam

Malayalam is thought to have diverged from Middle Tamil approximately the 6th century in the region coinciding with modern Kerala. The development of Malayalam as a separate language was characterized by a moderate influence from Sanskrit, both in lexicon and grammar, which culminated in the Aadhyaathma Ramayanam, a version of the Ramayana by Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan which marked the beginning of modern Malayalam. Ezhuthachan's works also cemented the use of the Malayalam script, an alphabet blending the Tamil Vatteluttu alphabet with elements of the Grantha script resulting in a large number of letters capable of representing both Indo-Aryan and Dravidian sounds.[73][74] Today, it is considered one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and was declared a classical language by the Government of India in 2013.[75]

Sino-Tibetan languages

Sino-Tibetan languages are spoken in the western Himalayas (Himachal Pradesh) and in the highlands of Northeast India. The Sino-Tibetan family includes such languages as Meitei (officially known as Manipuri), Tripuri, Bodo, Garo and various groups of Naga languages. Some of the languages traditionally included in Sino-Tibetan may actually be language isolates or part of small independent language families.

Meitei

Meitei language (officially known as Manipuri language) was the ancient court language of Manipur Kingdom (Meitei: Meeteileipak), which was used with honour before and during the kingdom's Durbar (court) sessions, until Manipur was merged into the Republic of India on 21 September 1949.[76][77] Besides being the native tongue of the Meiteis, Meitei language was and is the lingua franca of all the ethnic groups living in Manipur.[78][79] The ancestor of the present day Meitei language is the Ancient Meitei (also called Old Manipuri). Classical Meitei (also called Classical Manipuri) is the standardised form of Meitei and is also the liturgical language of Sanamahism (traditional Meitei religion), serving as the medium of thoughts on the Puya (Meitei texts).

Padma Vibhushan awardee Indian Bengali scholar Suniti Kumar Chatterji wrote about Meitei language:

"The beginning of this old Manipuri literature (as in the case of Newari) may go back to 1500 years, or even 2000 years, from now."[76][80]

Meitei language has its own script, the Meitei script (Meitei: Meitei Mayek), often but not officially referred to as the Manipuri script. The earliest known coin, having the script engraved on it, dated back to the 6th century CE. Renowned Indian scholar Kalidas Nag, after observing the Meitei writings on the handmade papers and agar pieces, opined that the Manipuri script belongs to the pre-Ashokan period. Ancient and medieval Meitei literature are written in this script.[81]

According to the "Report on the Archaeological Studies in Manipur, Bulletin No-1", a Meitei language copper plate inscription was found to be dated back to the 8th century CE. It is one of the preserved earliest known written records of Meitei language.[82]

In the 18th century CE, the usage of Meitei script was officially replaced by the Bengali script for any forms of writings in Meitei language right from the era of Meitei King Gharib Niwaj (Meitei: Pamheiba) (1690–1751), the Maharaja of Manipur kingdom. It was during his time Kangleipak, the Meitei name of the kingdom, was renamed with the Sanskrit name Manipur, thereby creating the mythical connecting legends with that of the Manipur (Mahabharata), which is clarified by the modern Indian Hindu scholars as a coastal region in Odisha, though eponymous with the Meitei kingdom.

In modern era, the "Manipur State Constitution Act 1947" of the once independent Manipur Kingdom accords Meitei language as the court language of the kingdom (before merging into the Indian Republic).[83][84][85][86][87]

In the year 1972, Meitei language was given the recognition by the National Sahitya Akademi, the highest Indian body of language and literature, as one of the major Indian languages.[88][89]

On the 20th August 1992, Meitei language was included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and made one of the languages with official status in India. The event was commemorated every year as the Meitei Language Day (officially called Manipuri Language Day).[90][91][92][93][94]

Starting from the year 2021, Meitei script (officially known as Meetei Mayek[lower-alpha 1]) was officially used, along with the Bengali script, to write the Meitei language, as per "The Manipur Official Language (Amendment) Act, 2021". It was declared by the Government of Manipur on 10 March 2021.[95]

In September 2021, the Central Government of India released ₹18 crore (US$2.3 million) as the first instalment for the development and the promotion of the Meitei language and the Meitei script in Manipur.[96][97][98]

Languages of other families in India

Austroasiatic languages

The Austroasiatic family spoken in East and North-east India. Austroasiatic languages include the Santal and Munda languages of eastern India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, and the Mon–Khmer languages spoken by the Khasi and Nicobarese in India and in Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and southern China. The Austroasiatic languages arrived in east India around 4000-3500 ago from Southeast Asia.[99]

Great Andamanese and Ongan languages

On the Andaman Islands, language from at least two families have spoken: the Great Andamanese languages and the Ongan languages. The Sentinelese language is spoken on North Sentinel Island, but contact has not been made with the Sentinelis; thus, its language affiliation is unknown. While Joseph Greenberg considered the Great Andamanese languages to be part of a larger Indo-Pacific family, it was not established through the comparative method but considered spurious by historical linguists. Stephen Wurm suggests similarities with Trans-New Guinea languages and others are caused by a linguistic substrate.[100]

Juliette Blevins has suggested that the Ongan languages are the sister branch to the Austronesian languages in an Austronesian-Ongan family because of sound correspondences between protolanguages.[101]

Isolates

The Nihali language is a language isolate spoken in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. Affiliations have been suggested to the Munda languages but they have yet to be demonstrated.

Scripts

Indus

The Indus script is the short strings of symbols associated with the Harappan civilization of ancient India (most of the Indus sites are distributed in present-day Pakistan and northwest India) used between 2600 and 1900 BCE, which evolved from an early Indus script attested from around 3500–3300 BCE. Found in at least a dozen types of context, the symbols are most commonly associated with flat, rectangular stone tablets called seals. The first publication of a Harappan seal was a drawing by Alexander Cunningham in 1875. Since then, well over 4000 symbol-bearing objects have been discovered, some as far afield as Mesopotamia. After 1500 BCE, coinciding with the final stage of Harappan civilization, use of the symbols ends. There are over 400 distinct signs, but many are thought to be slight modifications or combinations of perhaps 200 'basic' signs. The symbols remain undeciphered (in spite of numerous attempts that did not find favour with the academic community), and some scholars classify them as proto-writing rather than writing proper.

Brāhmī

The best-known inscriptions in Brāhmī are the rock-cut Edicts of Ashoka, dating to the 3rd century BCE. These were long considered the earliest examples of Brāhmī writing, but recent archaeological evidence in Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu suggest the dates for the earliest use of Tamil Brāhmī to be around the 6th century BCE, dated using radiocarbon and thermoluminescence dating methods.

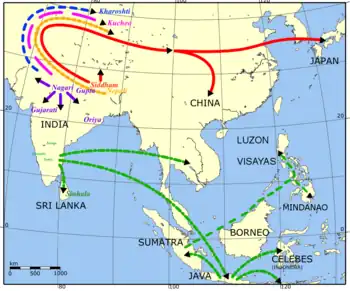

This script is ancestral to the Brahmic family of scripts, most of which are used in South and Southeast Asia, but which have wider historical use elsewhere, even as far as Mongolia and perhaps even Korea, according to one theory of the origin of Hangul. The Brāhmī numeral system is the ancestor of the Hindu-Arabic numerals, which are now used worldwide.

Brāhmī is generally believed to be derived from a Semitic script such as the Imperial Aramaic alphabet, as was clearly the case for the contemporary Kharosthi alphabet that arose in a part of northwest Indian under the control of the Achaemenid Empire. Rhys Davids suggests that writing may have been introduced to India from the Middle East by traders. Another possibility is with the Achaemenid conquest in the late 6th century BCE. It was often assumed that it was a planned invention under Ashoka as a prerequisite for his edicts. Compare the much better-documented parallel of the Hangul script.

Older examples of the Brahmi script appear to be on fragments of pottery from the trading town of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, which have been dated to the early 400 BCE. Even earlier evidence of the Tamil -Brahmi script has been discovered on pieces of pottery in Adichanallur, Tamil Nadu. Radio-carbon dating has established that they belonged to the 6th-century BCE.[102]

The origin of the script is still much debated, with most scholars stating that Brahmi was derived from or at least influenced by one or more contemporary Semitic scripts, while others favor the idea of an indigenous origin or connection to the much older and as yet undeciphered Indus script of the Indus Valley civilisation.[103][104]

Kharosthi

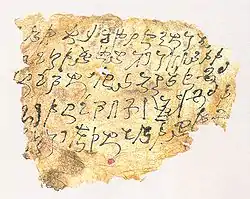

The Kharoṣṭhī script, also known as the Gāndhārī script, is an ancient abugida (a kind of alphabetic script) used by the Gandhara culture of ancient northwest India to write the Gāndhārī and Sanskrit languages. It was in use from the 4th century BCE until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE. It was also in use along the Silk Road where there is some evidence it may have survived until the 7th century CE in the remote way stations of Khotan and Niya.

Scholars are not in agreement as to whether the Kharoṣṭhī script evolved gradually, or was the work of a mindful inventor. An analysis of the script forms shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications to support the sounds found in Indian languages. One model is that the Aramaic script arrived with the Achaemenid conquest of the region in 500 BCE and evolved over the next 200+ years to reach its final form by the 3rd century BCE. However, no Aramaic documents of any kind have survived from this period. Also intermediate forms have yet been found to confirm this evolutionary model, and rock and coins inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE onward show a unified and mature form.

The study of the Kharoṣṭhī script was recently invigorated by the discovery of the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, a set of birch-bark manuscripts written in Kharoṣṭhī, discovered near the Afghan city of Haḍḍā (compare Panjabi HAḌḌ ਹੱਡ s. m. "A bone, especially a big bone of dead cattle" referring to the famous mortuary grounds if the area): just west of the Khyber Pass. The manuscripts were donated to the British Library in 1994. The entire set of manuscripts are dated to the 1st century CE making them the oldest Buddhist manuscripts in existence.

Gupta

The Gupta script was used for writing Sanskrit and is associated with the Gupta Empire of India which was a period of material prosperity and great religious and scientific developments. The Gupta script was descended from Brahmi and gave rise to the Siddham script and then Bengali–Assamese script.

Siddhaṃ

Siddhaṃ (Sanskrit, accomplished or perfected), descended from the Brahmi script via the Gupta script, which also gave rise to the Devanagari script as well as a number of other Asian scripts such as Tibetan script.

Siddhaṃ is an abugida or alphasyllabary rather than an alphabet because each character indicates a syllable. If no other mark occurs then the short 'a' is assumed. Diacritic marks indicate the other vowels, the pure nasal (anusvara), and the aspirated vowel (visarga). A special mark (virama), can be used to indicate that the letter stands alone with no vowel which sometimes happens at the end of Sanskrit words. See links below for examples.

The writing of mantras and copying of Sutras using the Siddhaṃ script is still practiced in Shingon Buddhism in Japan but has died out in other places. It was Kūkai who introduced the Siddham script to Japan when he returned from China in 806, where he studied Sanskrit with Nalanda trained monks including one known as Prajñā. Sutras that were taken to China from India were written in a variety of scripts, but Siddham was one of the most important. By the time Kūkai learned this script the trading and pilgrimage routes overland to India, part of the Silk Road, were closed by the expanding Islamic empire of the Abbasids. Then in the middle of the 9th century, there were a series of purges of "foreign religions" in China. This meant that Japan was cut off from the sources of Siddham texts. In time other scripts, particularly Devanagari replaced it in India, and so Japan was left as the only place where Siddham was preserved, although it was, and is only used for writing mantras and copying sutras.

Siddhaṃ was influential in the development of the Kana writing system, which is also associated with Kūkai – while the Kana shapes derive from Chinese characters, the principle of a syllable-based script and their systematic ordering was taken over from Siddham.

Nagari

Descended from the Siddham script around the 11th century.

See also

Notes

- The terms, "Meitei", "Meetei" and "Manipuri" are synonymous. While "Meitei" is more popular than "Meetei", "Meetei" is the officially mentioned synonym of the term "Manipuri".

References

- Turner, Sir Ralph Lilley. "A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan languages". Digital Dictionaries of South Asia. Oxford University Press (original), University of Chicago (web version). Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- "Introduction to Ancient Sanskrit". lrc.la.utexas.edu.

- Barbara A. West (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. pp. 282–. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- Bloch 1970, p. 32.

- Clara Lewis (16 April 2018). "Clamour grows for Marathi to be given classical language status". The Times of India. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- Novetzke 2016, pp. 53–54.

- Novetzke 2016, p. 53.

- Cynthia Talbot (20 September 2001). Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. pp. 211–213. ISBN 978-0-19-803123-9.

- Eaton, Richard M. (2005). The new Cambridge history of India (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-521-25484-1. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Sawant, Sunil R. (2008). "Nineteenth Century Marthi Literary Polysystem". In Ray, Mohit K. (ed.). Studies in translation (2nd rev. and enl. ed.). New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 134–135. ISBN 9788126909223.

- "Browse by Language Family". Ethnologue.

- Southworth 2005, pp. 249–250

- Southworth 2005, pp. 250–251

- Sivathamby, K (December 1974) Early South Indian Society and Economy: The Tinai Concept, Social Scientist, Vol.3 No.5 December 1974

- Lehmann 1998, p. 75

- Mahadevan 2003, pp. 90–95

- Lehmann 1998, p. 75. The dating of Sangam literature and the identification of its language with Old Tamil have recently been questioned by Herman Tieken who argues that the works are better understood as 9th-century Pāṇṭiyan dynasty compositions, deliberately written in an archaising style to make them seem older than they were (Tieken 2001). Tieken's dating has, however, been criticised by reviewers of his work. See e.g. Hart 2004, Ferro-Luzzi 2001, Monius 2002 and Wilden 2002

- Tharu & Lalita 1991, p. 70

- Lehmann 1998, pp. 75–6

- Krishnamurti 2003, p. 53

- Krishnamurti 2003, p. 92

- Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 182–193

- Steever 1998, p. 24

- Lehmann 1998, p. 80

- Kuiper 1958, p. 194

- Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 132–133

- Kuiper 1958, pp. 213–215

- Rajam 1985, pp. 284–285

- Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 173–174

- Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 153–154

- Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 145–146

- Mahadevan 2003, pp. 208–213

- Meenakshisundaran 1965, p. 119

- Varadarajan 1988

- Varadarajan 1988, pp. 155–157

- Zvelebil 1992, p. 227

- Shapiro & Schiffman 1983, p. 2

- Annamalai & Steever 1998, p. 100

- Steever 2005, pp. 107–8

- Meenakshisundaran 1965, p. 125

- Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 122–123

- Kandiah 1978, pp. 65–69

- Ramaswamy 1997

- Ramaswamy 1997: "Dravidianism, too, lent its support to the contestatory classicist project, motivated principally by the political imperative of countering (Sanskritic) Indian nationalism... It was not until the DMK came to power in 1967 that such demands were fulfilled, and the pure Tamil cause received a boost, although purification efforts are not particularly high on the agenda of either the Dravidian movement or the Dravidianist idiom of tamiḻppaṟṟu."

- Krishnamurti 2003, p. 480

- Kamath 2001, pp. 5–6

- Purva HaleGannada or Pre-old Kannada was the language of Banavasi in the early Christian era, the Satavahana and Kadamba eras (Wilks in Rice, B.L. (1897), p490)

- Sri K. Appadurai (1997). "The place of Kannada and Tamil in India's national culture". INTAMM. Archived from the original on 15 April 2007.

- Mahadevan 2003, p. 159 "earliest inscriptions in Kannada and Telugu occur more than half a millennium later [than the end of 3rd century or early 2nd century B.C.] ... earliest known literary work in Kannada is the Kavirajamarga, written early in the 9th century A.D."

- A family tree of Dravidian languages Archived 10 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Sourced from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Kittel (1993), p1-2

- "Literature in Kannada owes a great deal to Sanskrit, the magic wand whose touch raised Kannada from a level of patois to that of a literary idiom". (Sastri 1955, p309)

- "Declare Kannada a classical language". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 27 May 2005. Archived from the original on 5 January 2007.

- The word Isila found in the Ashokan inscription (called the Brahmagiri edict from Karnataka) meaning to shoot an arrow is a Kannada word, indicating that Kannada was a spoken language (Dr. D.L. Narasimhachar in Kamath 2001, p. 5)

- Ramesh (1984), p10

- A report on Halmidi inscription, Muralidhara Khajane (3 November 2003). "Halmidi village finally on the road to recognition". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 24 November 2003.

- Kamath 2001, p. 10

- "Press demand for according classical status to Kannada". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 17 April 2006. Archived from the original on 24 May 2006.

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p6

- Rice (1921), p13

- Kamath 2001, p. 58

- Azmathulla Shariff (26 July 2005). "Badami: Chalukyans' magical transformation". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 7 October 2006.

- In bilingual inscriptions the formulaic passages stating origin myths, genealogies, titles of kings and benedictions tended to be in Sanskrit, while the actual terms of the grant such as information on the land or village granted, its boundaries, the participation of local authorities, the rights and obligations of the grantee, taxes and dues and other local concerns were in the local language. The two languages of many such inscriptions were Sanskrit and the regional language such as Tamil or Kannada (Thapar 2003, pp393-394)

- N. Havalaiah (24 January 2004). "Ancient inscriptions unearthed". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 18 February 2004.

- Gururaj Bhat in Kamath 2001, p. 97

- Mukerjee, Shruba (21 August 2005). "Preserving voices from the past". Sunday Herald. Archived from the original on 22 October 2006.

- Charles Philip Brown, A Grammar of the Telugu language, Kessinger Publishing, p. 266

- "Telugu is 2,400 years old, says ASI". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 20 December 2007. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012.

- Nanisetti, Serish (14 December 2017). "Bommalagutta inscription sheds light on poetic use of Telugu". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 78–79

- APonline – History and Culture-Languages Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Telugu gets classical status". The Times of India. 1 October 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Aiyar, Swaminatha (1987). Dravidian theories. p. 286. ISBN 978-81-208-0331-2. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- "Malayalam". ALS International. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- "'Classical' status for Malayalam". The Hindu. Thiruvananthapuram, India. 24 May 2013.

- Sanajaoba, Naorem (1988). Manipur, Past and Present: The Heritage and Ordeals of a Civilization. Mittal Publications. p. 290. ISBN 978-81-7099-853-2.

- Mohanty, P. K. (2006). Encyclopaedia of Scheduled Tribes in India: In Five Volume. p. 149. ISBN 978-81-8205-052-5.

- "Manipuri language and alphabets". omniglot.com.

- "Manipuri language | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- Indian Literature - Volume 14 - Page 20 (Volume 14 - Page 20 ed.). Sahitya Akademi. 1971. p. 20.

- Paniker, K. Ayyappa (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections (Assamese-Dogri). Sahitya Akademi. p. 324. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- "মণিপুরি ভাষা ও লিপি – এল বীরমঙ্গল সিংহ | আপনপাঠ ওয়েবজিন" (in Bengali). 16 September 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Chishti, S. M. A. W. (2005). Political Development in Manipur, 1919-1949. p. 282. ISBN 978-81-7835-424-8.

- Sharma, Suresh K. (2006). Documents on North-East India: Manipur. Mittal Publications. p. 168. ISBN 978-81-8324-092-5.

- Tarapot, Phanjoubam (2003). Bleeding Manipur. Har-Anand Publications. p. 309. ISBN 978-81-241-0902-1.

- Sanajaoba, Naorem (1993). Manipur: Treatise & Documents. Mittal Publications. p. 369. ISBN 978-81-7099-399-5.

- Sanajaoba, Naorem (1993). Manipur: Treatise & Documents. Mittal Publications. p. 255. ISBN 978-81-7099-399-5.

- Hajarimayum Subadani Devi. "Loanwords in Manipuri and their impact" (PDF). sealang.net.

In 1972 the Sahitya Akademi, the highest body of language and literature of India recognized Manipuri (Manipuri Sahitya Parisad. 1986:82)

- "Dr Thokchom Ibohanbi - first Manipuri writer to get Akademi award : 24th feb22 ~ E-Pao! Headlines". e-pao.net.

- Bhardwaj, R. C. (1994). Legislation by Members in the Indian Parliament. Allied Publishers. p. 189. ISBN 978-81-7023-409-8.

- Khullar, D. R. Geography Textbook. New Saraswati House India Pvt Ltd. p. 188. ISBN 978-93-5041-243-5.

- Bhattacharyya, Rituparna (29 July 2022). Northeast India Through the Ages: A Transdisciplinary Perspective on Prehistory, History, and Oral History. Taylor & Francis. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-000-62390-1.

- "30th Manipuri Language Day observed : 21st aug21 ~ E-Pao! Headlines". e-pao.net. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "Manipuri Language Day observed in Manipur - Eastern Mirror". easternmirrornagaland.com. 20 August 2017.

- "GAZETTE TITLE: The Manipur Official Language (Amendment) Act, 2021". manipurgovtpress.nic.in.

- Laithangbam, Iboyaima (15 September 2021). "Centre has released ₹18 crore for promotion of Manipuri language, says State Education Minister". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- "Centre to release Rs 18 crore to promote Manipuri language | Pothashang News". Pothashang. 14 September 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- "State Education Minister says Center has released ₹18 crore to promote Manipuri language - Bharat Times". 15 September 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Sidwell, Paul. 2018. Austroasiatic Studies: state of the art in 2018. Presentation at the Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan, 22 May 2018.

- Wurm, S.A. (1977: 929). New Guinea Area Languages and Language Study, Volume 1: Papuan Languages and the New Guinea Linguistic Scene. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, Canberra.

- Blevins, Juliette (2007). "A Long Lost Sister of Proto-Austronesian? Proto-Ongan, Mother of Jarawa and Onge of the Andaman Islands". Oceanic Linguistics. 46 (1): 154–198. doi:10.1353/ol.2007.0015. S2CID 143141296.

- "Skeletons, script found at ancient burial site in Tamil Nadu". orientalthane.com.

- Salomon 1998, p. 20.

- Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). "Kharosti and Brahmi". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 122 (2): 391–393. doi:10.2307/3087634. JSTOR 3087634.

Sources

- Annamalai, E.; Steever, S.B. (1998). "Modern Tamil". In Steever, Sanford (ed.). The Dravidian Languages. Routledge. pp. 100–128. ISBN 978-0-415-10023-6.

- Bloch, J (1970). Formation of the Marathi Language. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2322-8.

- Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat, and Michael Witzel, The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization, EVJS, vol. 11 (2004), issue 2 (Dec)

- Ferro-Luzzi, G. Eichinger (2001). "Kavya in South India: Old Tamil Cankam Poetry". Asian Folklore Studies (Book Review). 60 (2): 373–374. doi:10.2307/1179075. JSTOR 1179075.

- Hart, George (January–March 2004). "Kavya in South India: Old Tamil Cankam Poetry". The Journal of the American Oriental Society (Book Review). 124 (1): 180–. doi:10.2307/4132191. JSTOR 4132191.

- Kamath, Suryanath U. (2001) [First published 1980]. A Concise History of Karnataka: From Pre-historic Times to the Present. Bangalore: Jupiter books. OCLC 7796041.

- Kandiah, Thiru (1978). "Standard Language and Socio-Historical Parameters: Standard Lankan Tamil". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 1978 (16): 59–76. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1978.16.59. S2CID 143499414.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77111-5.

- Kuiper, F. B. J. (1958). "Two problems of old Tamil phonology I. The old Tamil āytam (with an appendix by K. Zvelebil)". Indo-Iranian Journal. 2 (3): 191–224. doi:10.1163/000000058790082452. S2CID 161402102.

- Lehmann, Thomas (1998). "Old Tamil". In Steever, Sanford (ed.). The Dravidian Languages. Routledge. pp. 75–99. ISBN 978-0-415-10023-6.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Harvard Oriental Series vol. 62. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.

- Meenakshisundaran, TP (1965). A history of Tamil language. Poona: Linguistic Society of India.

- Monius, Anne E. (November 2002). "Kavya in South India: Old Tamil Cankam Poetry". The Journal of Asian Studies (Book Review). 61 (4): 1404–1406. doi:10.2307/3096501. JSTOR 3096501.

- Novetzke, Christian Lee (2016). The Quotidian Revolution: Vernacularization, Religion, and the Premodern Public Sphere in India. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54241-8.

- Rajam, V. S. (1985). "The Duration of an Action-Real or Aspectual? The Evolution of the Present Tense in Tamil". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 105 (2): 277–291. doi:10.2307/601707. JSTOR 601707.

- Ramaswamy, Sumathy (1997). Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, 1891–1970. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-585-10600-7.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- Scharfe, Harmut. Kharoṣṭhī and Brāhmī. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 122 (2) 2002, p. 391–3.

- Shapiro, Michael C.; Schiffman, Harold F. (1983). Language and society in South Asia. Dordrecht: Foris. ISBN 978-90-70176-55-6.

- Southworth, Franklin C. (2005). Linguistic Archaeology of South Asia. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-415-33323-8.

- Stevens, John. Sacred Calligraphy of the East. [3rd ed. Rev.] (Boston : Shambala, 1995)

- Steever, Sanford (1998). "Introduction". In Steever, Sanford (ed.). The Dravidian Languages. Routledge. pp. 1–39. ISBN 978-0-415-10023-6.

- Steever, Sanford (2005). The Tamil auxiliary verb system. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34672-6.

- Tharu, Susie; Lalita, K. (1991). Women writing in India : 600 B.C. to the present. The Feminist Press at the City University of New York. ISBN 978-1-55861-026-2.

- Tieken, Herman (2001). Kavya in South India: Old Tamil Cankam Poetry. Gonda Indological Studies, Volume X. Groningen: Egbert Forsten Publishing. ISBN 978-90-6980-134-6.

- Varadarajan, Mu. (1988). A History of Tamil Literature. Translated by Viswanathan, E.Sa. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1992). Companion studies to the history of Tamil literature. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09365-2.

- Wilden, Eva (2002). "Towards an Internal Chronology of Old Tamil Caṅkam Literature Or How to Trace the Laws of a Poetic Universe". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens (Book Review). 46: 105–133. JSTOR 24007685.

Further reading

- A Database of G.A. Grierson's Linguistic Survey of India (1904–1928, Calcutta).

- Grierson, Sir George Abraham (1906). The Pisaca languages of north-western India. The Royal asiatic Society, London.

- Gramophone recordings from the Linguistic Survey of India (1913–1929), Digital South Asia Library

External links

- Omniglot alphabets for Kharoṣṭhī, Brahmi, Siddham, Devanāgarī.

- Indian Scripts and Languages