Dutch India

Dutch India consisted of the settlements and trading posts of the Dutch East India Company on the Indian subcontinent. It is only used as a geographical definition, as there was never a political authority ruling all Dutch India. Instead, Dutch India was divided into the governorates Dutch Ceylon and Dutch Coromandel, the commandment Dutch Malabar, and the directorates Dutch Bengal and Dutch Suratte.

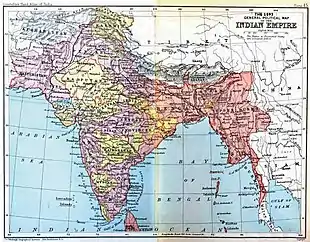

| Colonial India | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

The Dutch Indies, on the other hand, were the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) and the Dutch West Indies (present-day Suriname and the former Netherlands Antilles).

History

Dutch presence on the Indian subcontinent lasted from 1605 to 1825. Merchants of the Dutch East India Company first established themselves in Dutch Coromandel, notably Pulicat, as they were looking for textiles to exchange with the spices they traded in the East Indies.[1] Dutch Suratte and Dutch Bengal were established in 1616 and 1627 respectively.[2][3] After the Dutch conquered Ceylon from the Portuguese in 1656, they took the Portuguese forts on the Malabar coast five years later as well, as both are major spice producers, so as to create a Dutch monopoly for the spice trade.[4][5]

Apart from textiles, the items traded in Dutch India include precious stones, indigo, and silk across the Indian Peninsula, saltpetre and opium in Dutch Bengal, and pepper in Dutch Malabar. Indian slaves were exported to the Spice Islands and the Cape Colony.

In the second half of the eighteenth century the Dutch lost their influence more and more. The Kew Letters relinquished all Dutch colonies to the British, to prevent them from being overrun by the French. Although Dutch Coromandel and Dutch Bengal were restored to Dutch rule by virtue of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, they returned to British rule owing to the provisions of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824. Under the terms of the treaty, all transfers of property and establishments were to take place on 1 March 1825. By the middle of 1825, therefore, the Dutch had lost their last trading posts in India.

Coinage

Dutch mints in Cochin, Masulipatnam, Nagapatnam, Pondicherry (for the five years 1693–98 when the Dutch had gained control from the French), and Pulicat issued coins modelled on local Indian coinages.[6] Coins struck included:

The Dutch also imported coins struck in the Netherlands, including:

- the real, modeled on the Spanish colonial real, in denominations of 1⁄4, 1⁄2, 1, 2, 4, and 8 reals[9]

Gallery

Dutch trading ships in Negapatnam, Dutch Coromandel, circa 1680.

Dutch trading ships in Negapatnam, Dutch Coromandel, circa 1680. Factory in Hugli-Chuchura, Dutch Bengal. Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665.

Factory in Hugli-Chuchura, Dutch Bengal. Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665. The capture of Cochin from the Portuguese by Rijckloff van Goens in 1663. Atlas van der Hagen, 1682.

The capture of Cochin from the Portuguese by Rijckloff van Goens in 1663. Atlas van der Hagen, 1682. The remains of an old ruined Dutch Kuthi in Baranagar, India

The remains of an old ruined Dutch Kuthi in Baranagar, India The remainants of old Dutch Factory at Vengurla, Maharashtra

The remainants of old Dutch Factory at Vengurla, Maharashtra

See also

References

- "De VOCsite : handelsposten; Coromandel". De VOCsite. Jaap van Overbeek te Wageningen. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- "De VOCsite : handelsposten; Suratte". De VOCsite. Jaap van Overbeek te Wageningen. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- "De VOCsite : handelsposten; Bengalen". De VOCsite. Jaap van Overbeek te Wageningen. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- "De VOCsite : handelsposten; Ceylon". De VOCsite. Jaap van Overbeek te Wageningen. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- "De VOCsite : handelsposten; Malabar". De VOCsite. Jaap van Overbeek te Wageningen. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- UGC NET History Paper II Chapter Wise Notebook Complete Preparation Guide. EduGorilla. September 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- Report on the Working of the Archæological Researches in Mysore with the Government Review Thereon. University of Chicago. 1917. p. 89. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- Codrington, Humphrey William (1975). Ceylon Coins and Currency. Asian Educational Services. p. 258. ISBN 9788120609136. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- Bucknill, John A. S. (2000). The Coins of the Dutch East Indies: An Introduction to the Study of the Series. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120614482. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

.png.webp)