Blue and white pottery

"Blue and white pottery" (Chinese: 青花; pinyin: qīng-huā; lit. 'Blue flowers/patterns') covers a wide range of white pottery and porcelain decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment, generally cobalt oxide. The decoration is commonly applied by hand, originally by brush painting, but nowadays by stencilling or by transfer-printing, though other methods of application have also been used. The cobalt pigment is one of the very few that can withstand the highest firing temperatures that are required, in particular for porcelain, which partly accounts for its long-lasting popularity. Historically, many other colours required overglaze decoration and then a second firing at a lower temperature to fix that.

| Blue and white porcelain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Chinese blue and white jar, Ming dynasty, mid-15th century | |||||||

| Chinese | 青花瓷 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | "blue and white porcelain" | ||||||

| |||||||

The origin of the blue glazes thought to lie in Iraq, when craftsmen in Basra sought to imitate imported white Chinese stoneware with their own tin-glazed, white pottery and added decorative motifs in blue glazes.[1] Such Abbasid-era pieces have been found in present-day Iraq dating to the 9th century A.D., decades after the opening of a direct sea route from Iraq to China.[2]

In China, a style of decoration based on sinuous plant forms spreading across the object was perfected and most commonly used. Blue and white decoration first became widely used in Chinese porcelain in the 14th century, after the cobalt pigment for the blue began to be imported from Persia. It was widely exported, and inspired imitative wares in Islamic ceramics, and in Japan, and later European tin-glazed earthenware such as Delftware and after the techniques were discovered in the 18th century, European porcelain. Blue and white pottery in all of these traditions continues to be produced, most of it copying earlier styles.

Origin and development

Blue glazes were first developed by ancient Mesopotamians to imitate lapis lazuli, which was a highly prized stone. Later, a cobalt blue glaze became popular in Islamic pottery during the Abbasid Caliphate, during which time the cobalt was mined near Kashan, Oman, and Northern Hejaz.[4][5]

Tang and Song blue-and-white

The first Chinese blue and white wares were produced as early as the seventh century in Henan province, China during the Tang dynasty, although only shards have been discovered.[7] Tang period blue-and-white is more rare than Song blue-and-white and was unknown before 1985.[8] The Tang pieces are not porcelain however, but rather earthenwares with greenish white slip, using cobalt blue pigments.[8] The only three pieces of complete "Tang blue and white" in the world were recovered from Indonesian Belitung shipwreck in 1998 and later sold to Singapore.[9] It appears that the technique was forgotten for some centuries.[4]

Textual and archaeological evidence suggests that blue-and-white wares may have been produced during the Song dynasty, although the identification of Song dynasty blue-and-white pieces remains the subject of disagreement among experts.[10]

14th-century development

In the early 20th century, the development of the classic blue and white Jingdezhen ware porcelain was dated to the early Ming period, but consensus now agrees that these wares began to be made around 1300-1320, and were fully developed by the mid-century, as shown by the David Vases dated 1351, which are cornerstones for this chronology.[11][12] There are still those arguing that early pieces are mis-dated, and in fact go back to the Southern Song, but most scholars continue to reject this view.[13]

In the early 14th century, mass-production of fine, translucent, blue and white porcelain started at Jingdezhen, sometimes called the porcelain capital of China. This development was due to the combination of Chinese techniques and Islamic trade.[14] The new ware was made possible by the export of cobalt from Persia (called Huihui qing, 回回青, "Islamic blue" or “Muslim blue”), combined with the translucent white quality of Chinese porcelain, derived from kaolin.[14][15] Cobalt was so prized that manufacturers in Jingdezhen considered cobalt a precious commodity with about twice the value of gold.[14] Motifs also draw inspiration from Islamic decorations.[14] A large portion of these blue-and-white wares were then shipped to Southwest-Asian markets through the Muslim traders based in Guangzhou.[14]

Chinese blue and white porcelain was once-fired: after the porcelain body was dried, decorated with refined cobalt-blue pigment mixed with water and applied using a brush, it was coated with a clear glaze and fired at high temperature. From the 16th century, local sources of cobalt blue started to be developed, although Persian cobalt remained the most expensive.[14] Production of blue and white wares has continued at Jingdezhen to this day. Blue and white porcelain made at Jingdezhen probably reached the height of its technical excellence during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty (r. 1661–1722).

Evolution of Chinese blue and white ware

14th century

The true development of Chinese blue and white ware started with the first half of the 14th century, when it progressively replaced the centuries-long tradition of (normally) unpainted bluish-white southern Chinese porcelain, or Qingbai, as well as Ding ware from the north. The best, and quickly the main production was in Jingdezhen porcelain from Jiangxi Province. There was already a considerable tradition of painted Chinese ceramics, mainly represented at that time by the popular stoneware Cizhou ware, but this was not used by the court. For the first time in centuries the new blue and white appealed to the taste of the Mongol rulers of China.

Blue and white ware also began making its appearance in Japan, where it was known as sometsuke. Various forms and decorations were highly influenced by China, but later developed its own forms and styles.

Early blue and white ware, first half of 14th century, Jingdezhen.

Early blue and white ware, first half of 14th century, Jingdezhen. Blue and white vase from the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), Jingdezhen, unearthed in Jiangxi Province.

Blue and white vase from the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), Jingdezhen, unearthed in Jiangxi Province. Blue and white plate, Jingdezhen, Yuan dynasty (1271-1368).

Blue and white plate, Jingdezhen, Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). Blue and white jar, Jingdezhen, Yuan dynasty (1271-1368).

Blue and white jar, Jingdezhen, Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). Vase, before 1330

Vase, before 1330 The David Vases, 1351

The David Vases, 1351

15th century

With the advent of the Ming dynasty in 1368, blue and white ware was shunned for a time by the Court, especially under the Hongwu and Yongle Emperors, as being too foreign in inspiration.[14] Blue and white ware did not accord with Chinese taste at that time, the early Ming work Gegu Yaolun (格古要論) in fact described blue as well as multi-coloured wares as "exceedingly vulgar".[16] Blue and white porcelain however came back to prominence in the 15th century with the Xuande Emperor, and again developed from that time on.[14] In this century a number of experiments were made combining underglaze blue and other colours, both underglaze and overglaze enamels. Initially copper and iron reds were the most common, but these were much more difficult to fire reliably than cobalt blue, and produced a very high rate of mis-fired wares, where a dull grey replaced the intended red. Such experiments continued over the following centuries, with the doucai and wucai techniques combining underglaze blue and other colours in overglaze.

16th century

Some blue and white wares of the 16th century were characterized by Islamic influences, such as the ware under the Zhengde Emperor (1506–1521), which sometimes bore Persian and Arabic script,[17] due to the influence of Muslim eunuchs serving at his court.

By the end of the century, a large Chinese export porcelain trade with Europe had developed, and the so-called Kraak ware style had developed. This was by Chinese standards a rather low-quality but showy style, usually in blue and white, that became very popular in Europe, and can be seen in many Dutch Golden Age paintings of the century following; it was soon widely imitated locally.

Blue and white porcelain box, with Arabic and Persian inscriptions, Zhengde (1506-1521).

Blue and white porcelain box, with Arabic and Persian inscriptions, Zhengde (1506-1521)._in_Solos-Thuluth_calligraphy%252C_China%252C_Ming_dynasty%252C_Zhengde_period%252C_1506-1521_AD%252C_underglaze_painted_porcelain_-_Aga_Khan_Museum_-_Toronto%252C_Canada_-_DSC06903.jpg.webp)

.JPG.webp) Blue and white vase, Ming Wanli (1573-1620).

Blue and white vase, Ming Wanli (1573-1620). Blue and white jar, Ming Wanli (1573-1620).

Blue and white jar, Ming Wanli (1573-1620). Ming dynasty export porcelain highlighted in the CCCM Museum (Macau Museum) in Lisbon, Portugal

Ming dynasty export porcelain highlighted in the CCCM Museum (Macau Museum) in Lisbon, Portugal

17th century

During the 17th century, numerous blue and white pieces were made as Chinese export porcelain for the European markets. the Transitional porcelain style, mostly in blue and white greatly expanded the range of imagery used, taking scenes from literature, groups of figures and wide landscapes, often borrowing from Chinese painting and woodblock printed book illustrations. European symbols and scenes coexisted with Chinese scenes for these objects.[17] In the 1640s, rebellions in China and wars between the Ming dynasty and the Manchus damaged many kilns, and in 1656–1684 the new Qing dynasty government stopped trade by closing its ports. Chinese exports almost ceased and other sources were needed to fulfill the continuing Eurasian demand for blue and white. In Japan, Chinese potter refugees were able to introduce refined porcelain techniques and enamel glazes to the Arita kilns.

From 1658, the Dutch East India Company looked to Japan for blue-and-white porcelain to sell in Europe. Initially, the Arita kilns like the Kakiemon kiln could not yet supply enough quality porcelain to the Dutch East India Company, but they quickly expanded their capacity. From 1659–1740, the Arita kilns were able to export enormous quantities of porcelain to Europe and Asia. Gradually the Chinese kilns recovered, and by about 1740 the first period of Japanese export porcelain had all but ceased.[18] From about 1640 Dutch Delftware also became a competitor, using styles frankly imitative of the East Asian decoration.

.jpg.webp) Jingdezhen Kraak ware dish of typical shape. Width: 18 5/8 in. (47.3 cm).

Jingdezhen Kraak ware dish of typical shape. Width: 18 5/8 in. (47.3 cm). Transitional porcelain brush pot with episode from the story of Sima Guang

Transitional porcelain brush pot with episode from the story of Sima Guang Blue and white export porcelain, Qing Kangxi era, (1690-1700).

Blue and white export porcelain, Qing Kangxi era, (1690-1700). Export porcelain vase with European scene, Qing Kangxi era, (1690-1700).

Export porcelain vase with European scene, Qing Kangxi era, (1690-1700). Delftware bottle, c. 1675, tin-glazed earthenware

Delftware bottle, c. 1675, tin-glazed earthenware

18th century

In the 18th century export porcelain continued to be produced for the European markets.[17] Partly as a result of the work of Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles however, an early example of industrial spying in which the details of Chinese porcelain manufacture were transmitted to Europe, Chinese exports of porcelain soon shrank considerably, especially by the end of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor.[19]

Though polychrome decoration in overglaze enamels was now perfected, in the famille rose and other palettes, top-quality blue and white wares for the court and elite domestic markets continued to be produced at Jingdezhen.

Blue and white Chinese export porcelain (18th century).

Blue and white Chinese export porcelain (18th century). High-quality plate, Yongzheng reign, (1722-1735)

High-quality plate, Yongzheng reign, (1722-1735).jpg.webp) Flask with blue and red underglaze, a difficult technique, Qianlong reign, 1736-1795

Flask with blue and red underglaze, a difficult technique, Qianlong reign, 1736-1795

Outside China

Islamic pottery

Right image: Stone-paste dish with grape design, Iznik, Turkey, 1550-70. British Museum.

Chinese blue and white ware became extremely popular in the Middle-East from the 14th century, where both Chinese and Islamic types coexisted.[20]

From the 13th century, Chinese pictorial designs, such as flying cranes, dragons and lotus flowers also started to appear in the ceramic productions of the Near-East, especially in Syria and Egypt.[21]

Chinese porcelain of the 14th or 15th century was transmitted to the Middle-East and the Near East, and especially to the Ottoman Empire either through gifts or through war booty. Chinese designs were extremely influential with the pottery manufacturers at Iznik, Turkey. The Ming "grape" design in particular was highly popular and was extensively reproduced under the Ottoman Empire.[21]

Japan

The Japanese were early admirers of Chinese blue and white and, despite the difficulties of obtaining cobalt (from Iran via China), soon produced their own blue and white wares, usually in Japanese porcelain, which began to be produced around 1600. As a group, these are called sometsuke (染付). Much of this production is covered by the vague regional term Arita ware, but some kilns, like the high-quality Hirado ware, specialized in blue and white, and made little else. A high proportion of wares from about 1660-1740 were Japanese export porcelain, mostly for Europe.

The most exclusive kiln, making Nabeshima ware for political gifts rather than trade, made much porcelain only with blue, but also used blue heavily in its polychrome wares, where the decoration of the sides of dishes is typically only in blue. Hasami ware and Tobe ware are more popular wares mostly using in blue and white.

.jpg.webp) Large Arita ware dish, c. 1680, imitating Chinese export Kraak ware.

Large Arita ware dish, c. 1680, imitating Chinese export Kraak ware..gif) Japanese Arita ware blue and white underglaze porcelain tankard with Dutch silver lid of 1690

Japanese Arita ware blue and white underglaze porcelain tankard with Dutch silver lid of 1690.jpg.webp) Nabeshima ware bowl, Kyōhō era, 1716-1736

Nabeshima ware bowl, Kyōhō era, 1716-1736.jpg.webp) Japanese Hirado ware, water jar (for tea ceremony) with bamboo, 1st half 18th century

Japanese Hirado ware, water jar (for tea ceremony) with bamboo, 1st half 18th century

Korea

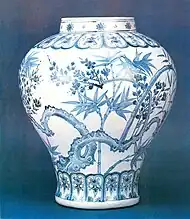

The Koreans began to produce blue and white porcelain in the early 15th century, with the decoration influenced by Chinese styles. Later some blue and white stoneware was also made. The historical production therefore all falls under the Joseon dynasty, 1392–1897. In vases, the typical wide shoulders of the shapes preferred in Korea allowed for expansive painting. Dragon and flowering branches were among the popular subjects.

Mid-15th century vase, National Treasure No. 219

Mid-15th century vase, National Treasure No. 219.jpg.webp) Lidded pot with plum blossom, National Treasure

Lidded pot with plum blossom, National Treasure 18th-century dragon jar

18th-century dragon jar.jpg.webp) Porcelain dish with cloud and crane design

Porcelain dish with cloud and crane design Wine bottle, 17th century

Wine bottle, 17th century

Early influences

Chinese blue-and-white ware were copied in Europe from the 16th century, with the faience blue-and-white technique called alla porcelana. Soon after the first experiments to reproduce the material of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain were made with Medici porcelain. These early works seem to be mixing influences from Islamic as well as Chinese blue-and-white wares.[22]

Blue relief vase, Florence, 2nd half of 15th century.

Blue relief vase, Florence, 2nd half of 15th century.

Vase alla porcelana, Cafaggiolo, Italy, 1520

Vase alla porcelana, Cafaggiolo, Italy, 1520

Direct Chinese imitations

By the beginning of the 17th century Chinese blue and white porcelain was being exported directly to Europe. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Oriental blue and white porcelain was highly prized in Europe and America and sometimes enhanced by fine silver and gold mounts, it was collected by kings and princes.

The European manufacture of porcelain started at Meissen in Germany in 1707. The detailed secrets of Chinese hard-paste porcelain technique were transmitted to Europe through the efforts of the Jesuit Father Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles between 1712 and 1722.[23]

The early wares were strongly influenced by Chinese and other Oriental porcelains and an early pattern was blue onion, which is still in production at the Meissen factory today. The first phase of the French porcelain was also strongly influenced by Chinese designs.

Early English porcelain wares were also influenced by Chinese wares and when, for example, the production of porcelain started at Worcester, nearly forty years after Meissen, Oriental blue and white wares provided the inspiration for much of the decoration used. Hand-painted and transfer-printed wares were made at Worcester and at other early English factories in a style known as Chinoiserie. Chelsea porcelain and Bow porcelain in London and Lowestoft porcelain in East Anglia made especially heavy use of blue and white. By the 1770s Wedgwood's jasperware, in biscuit stoneware and still using cobalt oxide, found a new approach to blue and white ceramics, and remains popular today.

Many other European factories followed this trend. In Delft, Netherlands blue and white ceramics taking their designs from Chinese export porcelains made for the Dutch market were made in large numbers throughout the 17th Century. Blue and white Delftware was itself extensively copied by factories in other European countries, including England, where it is known as English Delftware.

Kangxi era porcelain with French silver mount, 1717-1722

Kangxi era porcelain with French silver mount, 1717-1722 Dutch Delftware depicting Chinese scenes, 18th century. Musée Ernest Cognacq

Dutch Delftware depicting Chinese scenes, 18th century. Musée Ernest Cognacq Blue and white faience with Chinese scene, Nevers faience, France, 1680-1700.

Blue and white faience with Chinese scene, Nevers faience, France, 1680-1700.

Patterns

The plate shown in the illustration (left) is decorated, using transfer printing, with the famous willow pattern and was made by Royal Stafford; a factory in the English county of Staffordshire. Such is the persistence of the willow pattern that it is difficult to date the piece shown with any precision; it is possibly quite recent but similar wares have been produced by English factories in huge numbers over long periods and are still being made today. The willow pattern, said to tell the sad story of a pair of star-crossed lovers, was an entirely European design, though one that was strongly influenced in style by design features borrowed from Chinese export porcelains of the 18th century. The willow pattern was, in turn, copied by Chinese potters, but with the decoration hand painted rather than transfer-printed.

A blue and white Staffordshire Willow pattern plate

A blue and white Staffordshire Willow pattern plate Blue and white faience with Chinese scene, Nevers faience, France, 1680-1700.

Blue and white faience with Chinese scene, Nevers faience, France, 1680-1700.

Vietnam

A migration of Chinese potters to neighboring Vietnam during the Yuan dynasty is thought to be the beginnings of Vietnamese blue-and-white production.[24] However, the 15th-century Chinese occupation of Vietnam (1407–27) is considered to be the main period of Chinese influence on Vietnamese ceramics.[25] During this period, Vietnamese potters readily adopted cobalt underglaze, which had already gained popularity in export markets in the Muslim world. Vietnamese blue-and-white wares sometimes featured two types of cobalt pigment: Middle Eastern cobalt yielded a vivid blue but was more expensive than the darker cobalt from Yunnan, China.[15]

Chu Đậu village in Hải Dương province was the major ceramic manufacturer[26] From 1436 to 1465, China’s Ming dynasty abruptly ceased trade with the outside world, creating a commercial vacuum that allowed Vietnamese blue-and-white ceramics to monopolize the markets for sometimes, especially in Maritime Southeast Asia. Vietnamese wares of this era have been found all over Asia, from Japan, throughout Southeast Asia (Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines), to the Middle East (the Arabian port of Julfar, Persia, Syria, Turkey, Egypt), and Eastern Africa (Tanzania).[15][27][28][29]

%252C_14th_century_-_Stem_Cup_with_Dragon_Decoration_-_1989.360_-_Cleveland_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Vietnamese blue and white stem cup, Trần dynasty period, 14th century. Cleveland Museum of Art.

Vietnamese blue and white stem cup, Trần dynasty period, 14th century. Cleveland Museum of Art. Blue and white bowl with dragon texture, during Hồng Đức's years (1469-1497) of Later Lê dynasty. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Blue and white bowl with dragon texture, during Hồng Đức's years (1469-1497) of Later Lê dynasty. Metropolitan Museum of Art..jpg.webp) Plate with blue and white patterns, Mạc dynasty period, 16th century.

Plate with blue and white patterns, Mạc dynasty period, 16th century. Ewer in shape of a Vietnamese phoenix, a local folk animal, 15th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ewer in shape of a Vietnamese phoenix, a local folk animal, 15th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dish with phoenix and grapes decoration, Later Lê dynasty period, 15th century. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Dish with phoenix and grapes decoration, Later Lê dynasty period, 15th century. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Notes

- ""Tang Blue-and-White," by Regina Krahl" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- "Iraq and China: Ceramics, Trade, and Innovation". Archived from the original on 2017-09-19. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- Met description

- Medley, 177

- Lazaward (Lajvard) and Zaffer Cobalt Oxide in Islamic and Western Lustre Glass and Ceramics

- Bekken, Deborah A.; Niziolek, Lisa C.; Feinman, Gary M. (1 February 2018). China: Visions through the Ages. University of Chicago Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-226-45617-1.

- A Landmark in the History of Chinese Ceramics: The Invention of Blue-and-white Porcelain in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.)

- "Song blue-and-white was rare enough, but Tang blue-and-white was unheard of" in Chinese glazes: their origins, chemistry, and recreation Nigel Wood p.97

- curating the oceans and Belintung shipwreck

- Kessler 2012, pp. 1–16.

- Medley, 177

- Kessler 2012, p. 9.

- Kessler is a book devoted to arguing for earlier dates, as summarized in the Introduction. For earlier 20th century views, see p. 3 in particular. See Medley, p. 176 for a rejection of such dates.

- Finlay, p.158ff

- Gessert, Richard (February 15, 2022). "More Kinds of Blue". The Art Institute of Chicago.

- Kessler 2012, pp. 253–254.

- Musée Guimet permanent exhibit

- Ford & Impey, 126-127

- China's last empire: the great Qing William T. Rowe, Timothy Brook p.84

- Medieval Islamic civilization: an encyclopedia by Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach p.143

- Notice of British Museum "Islamic Art Room" permanent exhibit.

- Western Decorative Arts National Gallery of Art (U.S.), Rudolf Distelberger p.238

- Baghdiantz McCabe, Ina (2008) Orientalism in Early Modern France, ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0, Berg Publishing, Oxford, p.220ff

- Krahl, Regina (1997). "Vietnamese Blue-and-White and Related Wares". In Stevenson, John; Guy, John (eds.). Vietnamese Ceramics: A Separate Tradition. Art Media Resources. pp. 148–149. ISBN 1878529226.

- Krahl 1997, p. 149.

- "Chu Đậu ceramics". Archived from the original on 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- Vietnamese Ceramics in the Malay World

- Early History and Distribution of Trade Ceramics in Southeast Asia

- Ueda Shinya; Nishino Noriko (4 October 2017). "The International Ceramics Trade and Social Change in the Red River Delta in the Early Modern Period". Asian Review of World Histories. brill.com. 5 (2): 123–144. doi:10.1163/22879811-12340008. S2CID 135205531.

References

- Finlay, Robert, 2010, The Pilgrim Art. Cultures of Porcelain in World History. University of California Press ISBN 978-0-520-24468-9

- Ford, Barbara Brennan, and Oliver R. Impey, Japanese Art from the Gerry Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989, Metropolitan Museum of Art, fully online

- Kessler, Adam Theodore (2012). Song Blue and White Porcelain on the Silk Road. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-23127-6.

- Medley, Margaret, The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics, 3rd edition, 1989, Phaidon, ISBN 071482593X

External links

- Chinese Blue and White Porcelain at China Online Museum

- underglazedblue - Unique content and discussion on porcelain and collecting.

- A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

.jpg.webp)