Boro people

Boro (बर'/बड़ो [bɔɽo]), also called Bodo, is the largest ethnolinguistic group in the state of Assam, India. They are a part of the greater Bodo-Kachari family of ethnolinguistic groups and are spread across northeastern India. They are concentrated mainly in the Bodoland Territorial Region of Assam, though Boros inhabit all other districts of Assam[7] and Meghalaya.[8]

Boro[1] | |

|---|---|

Boro bwisagu dance in traditional attire | |

| Total population | |

| 1.45 million[2] (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Assam, Meghalaya | 1.41 million[3] (2011) |

| Languages | |

| Boro | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism, Bathouism, Christianity | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Assam |

|---|

|

Boros were listed under both "Boro" and "Borokachari" in The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950,[9] and are continued to be so called in Census of India documents.[10] Boros speak the Boro language, a Boro-Garo language of the Tibeto-Burman family, which is recognised as one of twenty-two Scheduled languages of India.[11] Over two-thirds of the people are bilingual, speaking Assamese as second language.[12] The Boro along with other cognate groups of Bodo-Kachari peoples are prehistoric settlers who are believed to have migrated at least 3,000 years ago.[13] Boros are mostly settled farmers, who have traditional irrigation, dong.[14]

The Boro people are recognised as a plains tribe in the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, and have special powers in the Bodoland Territorial Region, an autonomous division; and also as a minority people.[15]

Etymology

Boro is the self-designation or autonym of the community.[16] Boro comes from Bara-fisa, which means "son of Bara", and Bara stands for "man" or "male member" of the group.[17] In the cognate language Kokborok, Borok means man ('k' being a suffix for nouns) and so logically, Boro would mean man even in the Boro language.[18] Generally, the word Boro means a man, in the wider sense Boro means a human being (but not specific to a female member of the family) in the languages used by the Bodo-Kachari peoples.[19]

Language

The Boro language is a member of the Sino-Tibetan language family. It belongs to the Boro–Garo group of the Tibeto-Burman languages branch of the Sino-Tibetan family. It is an official language of the state of Assam and the Bodoland Territorial Region of India.[20] It is also one of the twenty-two languages listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India.[21]

Religion

Traditionally, Boros practised Bathouism, which is the worshiping of supreme God, known as Obonglaoree. The shijou tree (in the genus Euphorbia) is taken as the symbol of Bathou and worshiped. It is also claimed as the supreme god.[22] In the Boro language, Ba means five and thou means deep. Since Boros believe in the five mighty elements of God – land, water, air, fire, and ether – the number five has become significant in the Bathou culture, which is similar to the five elements of other Asian religions.

According to Bathouism, before the creation of the universe there was simply a great void, in which the supreme being 'Aham Guru', Anan Binan Gosai or Obonglaoree existed formlessly. Aham Guru became tired of living a formless existence and desired to live in flesh and blood. He descended on this great void with all human characteristics and created the universe.[23]

In addition to Bathouism, Boro people have also been converted to Hinduism, especially Hoom Jaygya. For this worship through fire ceremony, a clean surface near a home or courtyard is prepared. Usually, worship offerings include a betel nut called a 'goi' and a betel leaf called a 'pathwi' or 'bathwi' and rice, milk, and sugar. Another important Hindu festival, the Kherai Puja, where an altar is placed in a rice field, is the most important festival of the Boros. However, caste and dowry practices are not practised by the majority of Boro Hindus, who follow a set of rules called Brahma Dharma.[24] A majority of the Bodo people still follow Bathouism, but in censuses, they are often classified as Hindus, as their native religion has no official recognition under the Indian constitution.[25][26]

Christianity is followed by around 10% of the Boros and is predominantly of the Baptist denomination.[27] The major Boro Churches associations are the Boro Baptist Convention and Boro Baptist Church Association

History

After the breakup of Kamarupa around the 12th century till the colonial times (19th century) and beyond different ethnic groups settled in different ecological regions[28] but the constant movements and intermixing of peoples led to the development of distinctive but hybrid cultural practices.[29] According to Saikia (2012), even as different state systems emerged, expanded, and fell—such as the Mughals, the Koch, the Ahoms, and British colonialism—the Boros resisted entry into their fiscal systems and moved slowly but continuously to avoid them.[30] Due to the expansion of these states and the expansion of tenured peasantry,[31] the Boros were those who finally converged close to the forested regions of the lower Himalayan foothills.[32]

In this habitat, the Boros practised shifting cultivation[33] for self-sustenance and controlled forest products. To cultivate in this difficult terrain the Boros developed innovative low-cost irrigation systems that supported shifting cultivation.[34] Landholding, sowing and harvesting, irrigation, and hunting were all performed collectively.[35] As those who controlled forest based produce, they emerged as intermediaries in the trade in these as well as other goods between the plains and the hills and complex relationships developed. The Boros remained shifting cultivators at least till the 18th century and then slowly became less mobile;[36] even during the colonial period, most Boros refused permanent land tenure[37] or made no effort to secure landholding documents.[38]

When the Koch dynasty (1515–1949) consolidated its rule in the 16th century into the regions that the Boro people had settled in, it demarcated the region north of the Gohain Kamal Ali—which came to be called the Duars—as the region where non-Brahmin culture could thrive. After the Ahom kingdom consolidated its power in western Assam in the 17/18th century it made special arrangements with Bhutan to share administrative and fiscal responsibilities. But when the British banned forest lands from being used for cultivation in the last quarter of the 19th century the Boros suffered a major habitat loss since the forest lands historically used for shifting cultivation and the source of other produce suddenly became unavailable to them.[39] To alienate indigenous peasants from their lands was a stated colonial aim, to make them available as labour in other enterprises.[40]

Boro identity formation

Boros identity formation began in the colonial period,[41] when the Boro elite and intelligentsia began differentiating themselves from the Assamese caste-Hindu society.[42][43] The Boro, as well as many other communities as also much of the indigenous elite, were not exposed to education till the end of the 19th century, and it was by the early 20th century when a class of Boro/Kachari publicists finally emerged[44]—a small Kachari elite formed in the early 20th century from among traders, school teachers and contractors.[45] Foremost among them was Kalicharan Brahma, a trader from Goalpara who established a new monotheistic faith called "Brahma-ism" and most importantly, claimed for himself and his peers a new Bodo Identity.[46][47] Whereas earlier educated Kacharis like Rupnath had few options for social mobility other than assimilating into the Hindu lower castes, thus the Brahma religion developed by the Bodos that asserted respectable and autonomous Bodo identity while rejecting the cast dominance,[48][49] and by the 1921 census the Boros began giving up their tribal names and identifying themselves as Boro by caste and language and Brahma by religion.[50] Additional avenues, via conversion to Christianity, were already available by the late 19th century especially with the evangelical work of Sidney Endle who is also known for his tome "The Kacharis",[51] and this formed a parallel stream of Boro articulation till much later times.

Boro as a self-referential term for all Kacharis (including the Dimasas) was reported by Montgomery in 1838.[52] Bodo was a term reported by Brian Houghton Hodgson (1847) as a endonym that, he speculated, encompassed a wide group of peoples that included in the minimum the Mech and the Kacharis.[53] This led to two type of approaches to the Boro identity: one is the notion of a wide group was picked up by Kalicharan Brahma and his peers who posited the Boro identity in opposition to the caste-Hindu Assamese,[43] and the other one, Jadunath Khakhlari who accepted the notion for the greater Bodo race but at the same time criticised it as a neologism and insisted on the use of the name Kachari and pointed to the Kachari's contribution to the Assamese culture to underline their historical political legacy.[54] Those of the Kacharis who preferred to progress socially by initiation into the Ekasarana Dharma are called Sarania Kachari and are not considered as Boros today.

Pre-political Boro associations

The period from 1919 saw the emergence of different Boro organizations: Bodo Chatra Sanmilan (Bodo Students Association), Kachari Chatra Sanmilan (Kachari Students Association), Bodo Maha Sanmilan (Greater Bodo Association), Kachari Jatiyo Sanmilan (Kachari Community Association), etc.[55] These organizations pushed divergent means for social and political progress.[56] For example, Bodo Chatra Sanmilan advocated giving up tribal attributes and wanted women to follow the ideals of Sita of Ramayana.[57] Even as self-assertive politics was on, the Boros were not ready to severe their relationship with the greater Assamese society, with even Kalicharan Brahma advocating Assamese as the medium of instruction in schools,[58] and Boro associations seeking patronage from Assamese figures who showed sympathy for their cause.[59] In the absence of an acknowledged past history of state formation, the associations felt particularly pressed to show that the Boros were not primitive as some other tribal groups[60] and at the same time did not fall into the caste-Hindu hierarchy.[61]

The demand for community rights was made for the first time when at the 1929 Simon Commission the Boro leaders evoked colonial imagery of backward tribes and requested protection in the form of reserved representation in local and central legislatures.[62] The Boro delegation to the Simon Commission included, among others, Kalicharan Brahma and Jadav Khakhlari. The delegation submitted that Goalpara should remain with Assam and should not be included with Bengal; and that the Boros were culturally close to the Assamese.[63][58]

Boros in colonial tribal politics

The only human category in the pre-colonial times was jati.[64] In the early 19th century the East India Company became interested in the 'tribal' question owing to situations arising out of insurgencies against local rulers who were seeking British protection; but over the years the East India Company/British Raj evolved its role as saviors of the not the local rulers but the local people by offering to protect them against these rulers just as the primitive people of Africa needed protection. The notion of primitive vs non-primitive difference was further refined by the introduction of European notions of racial differences and by the census of 1872, categories such as 'aboriginal tribe' and 'semi-Hinduised aboriginals' emerged. The 1881 census proposed that India consisted of two hostile populations and thus did not possess a cohesive nationality. And by 1901 the official definition of a tribe was set down by Risley.[65] Within this formulation Northeast India was seen as a special case that required separate legislation.[66]

The elites from these social groups, including that from the Boros, used these categories for political articulation.[67] The Tribal League, a full political organisation, emerged in 1933[68] as the common platform for all plains tribes of the Brahmaputra valley[69] that included the Boro, Karbi, Mising, Tiwa and the Rabha.[70] This formation excluded the hills tribes which were not allowed political participation.[71] The colonial state and ethnographers' desire to define the tribal people, the need of the people to define themselves, and the earlier pre-political associations were significant contributory factors in the development of the tribal identity among the Boro and other groups.[72]

The Tribal League, which included Boro leaders such as Rabi Chandra Kachari and Rupnath Brahma, succeeded in protecting the Line system in 1937 against the proposal by the Muslim League.[73]

Demographics

Around 1.45 million Bodos are living in Assam, thus constituting 4.53% of the state population.[74] A majority of them around 68.96% alone are being concentrated in Bodoland Territorial Region of Assam, numbering 1 million out of total 3.15 million population, thus constituting 31% of the region's population.[75][76][77] In Bodoland's capital Kokrajhar, they are in minority, forming only 25% of the town's population.[78]

Folk tradition and mythology

The history of the Boro people can be explained from folk traditions. According to Padma Bhushan winner Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, mythologically, Boros are "the offspring of son of the Vishnu (Baraha) and Mother-Earth (Basumati)" who were termed "Kiratas" during the Epic period.[79]

Social groups

Aroi or Ari or Ary is a suffix in Boro language, which means folk.

Some of the important clans of Boros are:[80]

- Swargiary: The priestly clan, with Deoris and Ojhas selected from this clan.

- Basumatary: The land-holding clan.

- Narzary: The clan associated with the jute cultivation and supply.

- Mosahary: This clan is associated with the protection of cattle.

- Goyary: This clan is associated with the cultivation of areca nuts.

- Owary: This clan is associated with the supply of bamboos.

- Khakhlary: This clan is associated with the supply of Khangkhala plant required for kherai puja.

- Daimary: This clan is associated with the river.

- Lahari: This clan is associated with the collection of leaves in large quantities for the festival.

- Hajoary: The Boros that lived in the hills and foothills.

- Kherkatari: The Boros associated with thatch and its supply, found mostly in Kamrup district.

- Sibingari: The Boros traditionally associated with raising and supply of sesame.

- Bingiari: The Boros associated with musical instruments.

- Ramchiary: Ramsa is place name in kamrup. It is the name by which Boros were known to their brethren in the hills.

- Mahilary: This clan is associated with collection of tax from Mahallas. Mahela and Mahalia are the variant forms of Mahilary clan.

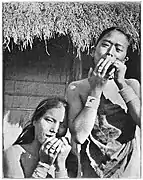

Gallery

Boro women at Hornbill Festival

Boro women at Hornbill Festival Kherai Group Dance

Kherai Group Dance Boro woman playing harp

Boro woman playing harp

Notable people

- Rajni Basumatary[81] Filmmaker and actress

- Ankushita Boro,[82] Indian boxer

- Jamuna Boro,[83] Indian boxer

- Pramod Boro,[84] Former President of ABSU, President of UPPL, CEM of Bodoland Territorial Council

- Harishankar Brahma[85] 19th Chief Election Commissioner of India

- Upendra Nath Brahma,[86] Boro activist, known by the title Bodofa[87]

- Sansuma Khunggur Bwiswmuthiary,[88] former Member of parliament

- Hagrama Mohilary,[89] president of Bodoland People's Front political party and former Chief Executive Member of Bodoland Territorial Council.

- Ranjit Shekhar Mooshahary,[90] former governor of Meghalaya, retired IPS officer, former director-general of National Security Guards (NSG) and the Border Security Force (BSF)

- Halicharan Narzary,[91] Indian footballer

- Proneeta Swargiary[92] Dance India Dance (season 5) Winner

See also

References

- By 1921 the census reported that many Kacharis had abandoned tribal names and were describing themselves as Bara by caste and language(Sharma 2011:211)

- "Census report 2011" (PDF). Retrieved 5 January 2020. Note: The number are for the L1 speakers of the Boro language

- "C -16 C-16 Population By Mother Tongue - Assam". census.gov.in. Retrieved 23 August 2020. Note: the number of L1 speakers of the Boro language, which is likely a lower estimate of the number of ethnic Boro people.

- "639 Identifier Documentation: aho – ISO 639-3". SIL International (formerly known as the Summer Institute of Linguistics). SIL International. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

Ahom [aho]

- "Population by Religious Communities". Census India – 2001. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

Census Data Finder/C Series/Population by Religious Communities

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

2011census/C-01/DDW00C-01 MDDS.XLS

- (Dikshit 2013:376)

- "Meghalaya - Data Highlights: The Scheduled Tribes - Census of India 2001" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- "the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2022.

- "ST-14: Scheduled tribe population by religious community (district level), Assam, district Sonitpur - 2011". Archived from the original on 30 January 2023.

- "List of languages in the Eighth Schedule" (PDF).

- (Dikshit 2013:375)

- "Most scholars suggest that the first Tibeto-Burman-speaking peoples began to enter Assam at least 3,000 years ago." (DeLancey 2012:13–14)

- Devi, Chandam Victoria (1 April 2018). "Participatory Management of Irrigation System in North Eastern Region of India". International Journal of Rural Management. 14 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1177/0973005218765552. ISSN 0973-0052.

- "Boro (Bodo)". Minority Rights Group. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- "The people very seldom call themselves by any other name other than Bodo or Boro".(Mosahary 1983:42)

- "...we have references to the term Bara-fisa meaning child of the Baras and the term Bara-fisa must have been subsequently termed as simply as Bara pronounced as Boro. Dr P C Bhattacharya writes that like other tribal names in Assam the name Bara stands for man or male member (Mosahary 1983:44)

- (Brahma 2008:1) In closely allied Tripura language, “Boro” is pronounced as “Borok” which means Man.

- (Brahma 2008:1)

- "The Assam Official Language (Amendment) Act, 2020" (PDF).

- "Languages Included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution".

- Basumatary, Dhuparam. Boro Kachari Sonskritir Kinchit Abhas. pp. 2–3.

- Basumatary, Dhuparam. Boro Kachari Sonskritir Kinchit Abhas. pp. 2–3.

- "HOME". udalguri.gov.in. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "NCM asked to clarify stand on status of Bodo tribe's religion". The Times of India. 6 September 2012.

- "Indian Census shall now recognize 'Bathouism' officially". 6 February 2019.

- "Hundreds of Bodo-Christians joined a massive rally addressed by Indias PM but skepticism remains". southasiajournal.net. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- "Several communities inhabiting these areas since precolonial times, which include the Bodo, Garo, Khasi, Bhutia, Rajbanshi, etc, had settled across a wider geography characterised by similar ecological features (Nathan 1936). Over the second millennium of our common era, the process for consolidation of these habitats began. The Bodos, too, underwent this process." (Saikia 2012:17)

- "The historical movement of populations was often determined by local ecological pressures like a crisis of resources to support an increasing population or natural disturbances like the rapid change in the course of some river. The visible absence of boundaries representing the nation state also allowed a free flow of people. The region thus helped in the growth of a distinctively hybrid space of ecology and linguistic practices." (Saikia 2012:17)

- "The Bodos were continuously, albeit slowly, on the move for a long period. This practice was fairly true for most communities who resisted any entry into the formal state-led fiscal system whether it was the Mughal, Koch and Ahom rulers or the British colonial government." (Saikia 2012:17)

- "The consolidation of the Hindu Assamese peasantry in the flat fertile valley over the past few centuries had demarcated agrarian boundaries. The tribal peasantry was further boxed inside a fixed geography, a process that made them strangers within the Hindu Assamese agrarian territory." (Saikia 2012:17)

- "Historically, they lived closer to the forested areas along the foothills of the lower Himalayan ranges (Allen 1905)" (Saikia 2012:15)

- "All these accounts confirm that the Bodo tribe followed slash and burn cultivation. Although wet rice cultivation and plow were a characteristic of the Indo-Aryans, Bodos transitioned from using these methods of cultivation by the 1870s due to closer contact with settled populations." (Daimari & Bedamatta 2021:709)

- "The Bodos have innovatively re-engineered the water flow into these areas and created a localised irrigation system (Guha 1982). But this did not support an overall production of surplus crop... The low-cost irrigation works facilitated through community labour did not stand against their tradition of shifting agriculture..." (Saikia 2012:15)

- "[H]istorically the Bodos have practised communal landownership. This was equally true in their preference for collective labour which was needed for irrigation works and during the sowing or harvesting seasons; even hunting was a collective effort." (Saikia 2012:16)

- "For long, the Bodo remained shifting cultivators in a flat valley. At least till the 18th century, they were yet to be fixed into a permanent geography. This meant they would hardly practise a permanent form of cultivation though slowly they became less mobile" (Saikia 2012:16)

- "During colonial rule, a majority of Bodo peasants, like many others in the Brahmaputra Valley refused to accept permanent land tenure." (Saikia 2012:16)

- "Colonial rule even failed to infuse a permanent nature of cultivation among the Bodos. This was true for most tribal communities of the region. The Bodos rarely tried to secure written records of landownership." (Saikia 2012:16)

- (Saikia 2012:16–17)

- "A principal aim in mid-19th century Assam was to flush out native peasants from the land, as documented in government reports and arbitrary land revenue increments. They were to be coerced into surrendering what Marx called "conditions of labour" to the tea planters; an achievement that was to ensure a ready reserve army of labour." (Das & Saikia 2011:73)

- Saikia (2017, pp. 160–161)

- "From the colonial period, the Bodos have been defining themselves as a community in opposition to other communities. The Bodo-educated elites and intelligentsia have been articulating their divergence from the Assamese caste Hindu society and highlighting issues like land alienation and social and economic backwardness." (Pathak 2012:20)

- "Bodos, who have historically shared their home with other communities in the Assam valley, were one of the first communities in the plains to challenge the Assamese hegemony. Under a broader appellate of Bodo-Kachari, they galvanized a political movement, mobilizing a separate identity from the caste-Hindu Assamese community." (Saikia 2017:161)

- "Twentieth-century Bodo Kachari publicists contributed an important new voice to Assam’s public sphere. Until the late nineteenth century few Kacharis had the wherewithal to obtain a high school or college education." (Sharma 2011:208)

- "By the early twentieth century a small Kachari public emerged from among petty traders, schoolteachers, and small-time contractors. Its participants sought out alternatives to the limited mobility offered by established Hinduism." (Sharma 2011:210)

- "The founder of this movement was Kalicharan (1860–1938), a Kachari trader based in Goalpara. A Bengali mendicant, Sibnarayan Paramhansa, inspired him to venerate Brahma, the Supreme Soul. Kalicharan summoned comrades to join him in a new, monotheistic faith whose members adopted a new surname, Brahma, in place of their older, demeaning tribal names. Simultaneously they claimed a new Bodo identity." (Sharma 2011:211)

- "Kalicharan Brahma, Sitanath Brahma Choudhary among the Kacharis and Samsonsing Ingti among the Mikirs were the real pioneers. Their attempts to redefine tradition, adjusting to colonial modernity, were also the first steps towards the construction of the tribal identity." (Pathak 2010:62)

- "Modernizing Bodos felt that they had to distinguish themselves from savage tribal neighbours such as Nagas while resisting caste domination."(Sharma 2011:213)

- "Previously, educated Kacharis like Rupnath possessed few options for social mobility other than absorption into the Hindu lower castes. The Brahma religion offered him and his peers a new opportunity to assert a respectable and autonomous Bodo identity." (Sharma 2011:211)

- "By 1921 the census reported that many Kacharis had abandoned tribal names and were describing themselves as Bara [sic] by caste and language, and Brahma by religion." (Sharma 2011:211)

- "Quite in Hodgson’s fashion, the S.P.G. missionary Sidney Endle, who wrote about the Kacharis at the end of the nineteenth century, praised them as diligent aboriginals. But he was less interested in their economic redemption than in the spiritual. Endle’s main objective was the Christian conversion of his Kachari flock." (Sharma 2011:210)

- "In fact, colonial officials seemed aware that Boro was a self-referential term. For instance, in 1838 Martin Montgomery reported that: "The Kachharis form a tribe, ..." (Daimari 2022:14)

- "As (Hodgson) admits in the end, his way of seeing the "Bodos" is twofold: he starts by using "Bodo" to designate a wide range of people (“a numerous race”), then wonders if some others are not "Bodos in disguise". He ends on a cautionary note and refrains from unmasking the dubious tribes, registering only the Mechs and Kacharis,..." (Jacquesson 2008:21)

- "Jadunath accepted the notion of a greater Bodo race which would unite different groups. Yet in contrast to Kalicharan and his followers, he wished to retain the name Kachari. He criticized the term Bodo as a neologism which denied the Kachari historical legacy: If we ourselves see the name Kachari as shameful so will other groups. In this manner Jadunath sought to reclaim past Kachari contributions to Assamese culture and literature. He reminded his readers that the Kachari language [was the one] from whose roots sprang the present Asomiya language, whose king was the first patron of the religion and its books. Jadunath voiced the views of those Bodos who felt that they might lose their claim to the rich heritage of Assam’s medieval Kachari and Koch kingdoms." (Sharma 2011:213)

- (Sharma 2011:212–213)

- "It is not easy to reconstruct the thoughts and actions of this nascent Bodo public, since constituents had limited access to social capital and print media. Ideas and structures were constantly in flux as they flowed through multiple organizations and meetings. Fragmentary traces of Bodo publicists' ideas appear in the rare pamphlets that have survived in archives. These reveal the divergent approaches to social progress that were on offer." (Sharma 2011:213)

- "Association members were urged to abjure pork, alcohol, and the practice of animal sacrifice to the gods. Bodo women were exhorted to follow the examples of legendary females such as the virtuous wife Sita of the Ramayana epic in their lives and conduct." (Sharma 2011:213)

- "On the question of territorial transfer of Goalpara to Bengal, members of the various Kachari organisations claimed themselves to be Assamese on the basis of cultural affinity. As mentioned earlier, Kalicharan Brahma's efforts to introduce Assamese as the medium of instruction also point to a parallel political and cultural identification to an Assamese identity." (Pathak 2010:62)

- "The Bodo associations often sought patronage from established Assamese figures who showed sympathy to the Bodo cause. For example, the tea planter Bisturam Barua received the title of Kachari Raja for his financial support of the community's events." (Sharma 2011:212)

- "In the vacuum created by the absence of an acknowledged history of state formation, colonial observers and Assamese élites had wrongly dismissed Bodo Kacharis as a primitive people." (Sharma 2011:213)

- "Modernizing Bodos felt that they had to distinguish themselves from savage tribal neighbours such as Nagas even while resisting caste domination.

- "In order to safeguard their interests, "the community demanded separate representative in the local council and one reserved seat for the Bodos in the Central Legislature". They deplored their backwardness and recognised education as a means of development and fight against exploitation. They complained that they were illiterate because "our people are always misled, they cannot understand the value of reforms, they cannot save themselves from the hands of the foreign moneylenders". The leaders, as representatives of respective tribes, used the colonial imagery of the tribe as backward, semi-savage, ignorant to put forward their political claims and for seeking colonial protection." (Pathak 2010:62)

- "Goalpara is a part and parcel of Assam and history will prove what part she has been playing since the time immemorial. The habits and customs of the people of this district are more akin to Assamese than to Bengalis. We the Bodos can by no means call ourselves other than Assamese. The transfer of this district to Bengal will be prejudical to the interest not only of this community, but all the other communities, and this transfer will seriously hamper our progress in all directions." - part of the text of the memorandum to the Simon Commission.

- "Nowadays in the North-East, “tribe” and “caste” are very commonly used as such, i.e. in English. It is worthwhile, however, underlining that this dichotomy does not exist in the Assamese language itself nor in other Indo-Aryan languages in India, which do not differentiate between different sorts of human “kinds” or “species”, jāti." (Ramirez 2014:18)

- (Gupta 2019:109–112)

- "While this largely pertained to central and southern India, the northeast was shown to have had a somewhat different trajectory, where indigenous communities represented a third category which descended from the ‘great wave of Mongoloid immigration southward’. It was stated that since the Indo-Aryans did not penetrate these areas till long after their own original traditions had been lost, the northeast constituted a discrete space, requiring separate legislation." (Gupta 2019:112)

- "The "Plains Tribes" category was invented by the colonial authorities to ethnographically classify the tribal section of the population in the plains, which was later, after the 1935 Act, given the status of a separate constituency. The tribal elite appropriated this construction to articulate their political aspirations. (Pathak 2010:62)

- "The early 20th century saw the emergence of various associations within these communities, which culminated in the emergence of the Tribal League in 1933." (Pathak 2010:62)

- "The formation and emergence of the Tribal League in 1933 as a common platform of all the Plains Tribes also involved a parallel process in self-representation. The numerically small, educated tribal elite attempted to define their tribal identity as a "community of the Plains Tribes". The Tribal League envisioned the unity of the various tribal communities. Thus, there emerged the single, monolithic notion of the "Plains Tribes". (Pathak 2010:62)

- "'Plains Tribes' is a term used in the contemporary political and administrative discourse from the 1930s when it was introduced by the British as a generic term clubbing the valley tribes like the Kacharis (Bodos), Mikirs (Karbis), Miris (Mishings), Lalung (Tiwa) and Rabhas together." (Pathak 2010:61)

- "While the hill tribes of north-east India were constrained by colonial laws barring them from active politics, the plain tribes were not." (Pathak 2010:61)

- "Parallel to the efforts of the colonial state and ethnographers to define and locate the "tribal" of the Brahmaputra valley... The Mels inspired tribal conventions (like the Kachari convention, Miri convention, etc), matured the nascent "tribal" consciousness, which resulted in the formation of the Tribal League as a mode of organised tribal politics." (Pathak 2010:61)

- "In 1937, the Muslim League moved a resolution for the abolition of the Line system.21 Members of the Tribal League, Rabi Chandra Kachari, and Rupnath Brahma opposed the resolution and it was eventually withdrawn. (Pathak 2010:62)

- "Assam records decline in percentage of Assamese, Bodo, Rabha, Mishing speakers". 28 June 2018.

- Singh, Bikash (10 May 2014). "Why peace in Bodoland always ephemeral and lasts only till next carnage". The Economic Times.

- "A revival of the decades-old Bodoland movement in Assam spells trouble for the BJP". 17 October 2017.

- "Assam attack: Calls for separate state by Bodo leaders keep region unstable". 6 August 2016.

- "Bodos are minority on their turf". 3 January 2015.

- "RCILTS, Phase-II". iitg.ac.in. Archived from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- (Brahma 1998:15–22)

- "Actress to screen conflict tale in rural BTAD". 31 May 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Kapadia, Novy (30 November 2017). "Indian boxing witnesses its finest hour in the World Youth Boxing Championships". The Week. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "How the 19-Year-Old Daughter of a Vegetable Seller in Assam Became an International Boxer". The Better India. 5 August 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "Bodoland Territorial Council Election Results 2020: Pramod Boro New Chief Executive Member of BTC as BJP Extends Support to UPPL". in.news.yahoo.com. 13 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- "The Assam Tribune Online". www.assamtribune.com. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "Bodofa Upendra Nath Brahma's death anniversary observed by hundreds of people in Kokrajhar". The Sentinel. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Desk, Sentinel Digital (2 May 2019). "Bodofa Upendra Nath Brahma's death anniversary observed by hundreds of people in Kokrajhar - Sentinelassam". www.sentinelassam.com. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "BPF names Chandan Brahma for Kokrajhar". 25 March 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- "BTC Chief Hagrama Mohilary celebrates 50th Birth Anniversary in Udalguri - Sentinelassam". The Sentinel. 1 March 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- "BSF gets first Bodo DG". The Hindu. 11 January 2005. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "NEFU Player Holicharan Narzary Ties Knot With Geetanjali Deori". The Sentinel. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Proneeta Swargiary crowned winner of 'DID 5'". 11 October 2015.

Bibliography

- Brahma, Kameswar (1998). A Study in Cultural Heritage of the Boros. Assam Institute of Research for Tribals and Scheduled Castes.

- Brahma, Nirjay Kumar (2008). "Introduction: Interpretation of Bodo or Boro". Socio political institutions in Bodo society (PhD). Guwahati University. hdl:10603/66535.

- Daimari, James (2022). Colonial Knowledge and the Quest for Unnati among the Boros of North-East India, 1880s-1940s (PhD thesis). IIT Guwahati.

- Daimari, Mizinksa; Bedamatta, Rajshree (2021). "The State of Bodo Peasantry in Modern-Day Assam: Evidence from Majrabari Village in the Bodoland Territorial Area Districts". The Indian Journal of Labour Economics. 64 (3): 705–730. doi:10.1007/s41027-021-00328-8. S2CID 240506155.

- Das, Debarshi; Saikia, Arupjyoti (2011). "Early Twentieth Century Agrarian Assam: A Brief and Preliminary Overview". Economic and Political Weekly. 46 (41): 73–80. JSTOR 23047190.

- DeLancey, Scott (2012). Hyslop, Gwendolyn; Morey, Stephen; w. Post, Mark (eds.). "On the Origin of Bodo–Garo". Northeast Indian Linguistics. 4: 3–20. doi:10.1017/UPO9789382264521.003. ISBN 9789382264521.

- Dikshit, K. R. (2013). North-East India: Land, People and Economy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 375–376. ISBN 978-94-007-7055-3.

- Gupta, Sanjukta Das (2019). "Imagining the 'Tribe' in Colonial and Post-colonial India". Politeja. 16 (2(59)): 107–121. doi:10.12797/Politeja.16.2019.59.07. hdl:11573/1366269. JSTOR 26916356. S2CID 212430509.

- Jacquesson, François (2008). "Discovering Boro-Garo" (PDF). History of an Analytical and Descriptive Linguistic Category. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Mosahary, R N (1983). "The Boros: Their Origin, Migration and Settlement in Assam" (PDF). Proceedings of Northeast India History Association. Barapani: Northeast India History Association. pp. 42–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Pathak, Suryasikha (2010). "Tribal Politics in the Assam: 1933-1947". Economic and Political Weekly. 45 (10): 61–69. JSTOR 25664196.

- Pathak, Suryasikha (2012). "Ethnic Violence in Bodoland". Economic and Political Weekly. 47 (34): 19–23. JSTOR 41720055.

- Ramirez, Philippe (2014). People of the margins : across ethnic boundaries in North-East India. Guwahati: Spectrum. ISBN 9788183440639.

- Saikia, Arupjyoti (2012). "The Historical Geography of the Assam Violence". Economic and Political Weekly (analysis). 47 (41): 15–18. JSTOR 41720234.

- Saikia, Simtana (2017). Explaining Divergent Outcomes of the Mizo and Bodo Conflicts in the Ethno-Federal Context of India's Northeast (PDF) (PhD). London: King's College. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- Sharma, Jayeeta (2011). Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India (PDF). Duke University Press.

Further reading

- Deka, Hira Moni (2009). "The Historical Background of Bodo Movement". Politics of identity and the bodo movement in Assam (PhD). Guwahati University. hdl:10603/67844.

- Endle, Sidney (1911). The Kacharis. MACMILLAN AND CO. LIMITED.

- Kakoty, Suchitra (1981). "The Historical Background of the Bodo-Kacharis". A study of the educational development of the bodo tribe during the post independence period with particular reference to the northern region of Assam (PhD). Guwahati University. hdl:10603/67775.

- Siiger, Halfdan (2015). The Bodo of Assam: Revisiting a Classical Study from 1950 (PDF). NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-7694-160-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2020.

External links

Media related to Bodo people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bodo people at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)