Dimasa Kingdom

The Dimasa Kingdom[4] (also Kachari kingdom[5]) was a late medieval/early modern kingdom in Assam, Northeast India ruled by Dimasa kings.[6][7][8] The Dimasa kingdom and others (Kamata, Chutiya) that developed in the wake of the Kamarupa kingdom were examples of new states that emerged from indigenous communities in medieval Assam as a result of socio-political transformations in these communities.[9] The British finally annexed the kingdom: the plains in 1832[10] and the hills in 1834.[11] This kingdom gave its name to undivided Cachar district of colonial Assam. And after independence the undivided Cachar district was split into three districts in Assam: Dima Hasao district (formerly North Cachar Hills), Cachar district, Hailakandi district. The Ahom Buranjis called this kingdom Timisa.[12]

Dimasa Kingdom | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13th century CE–1832 | |||||||||

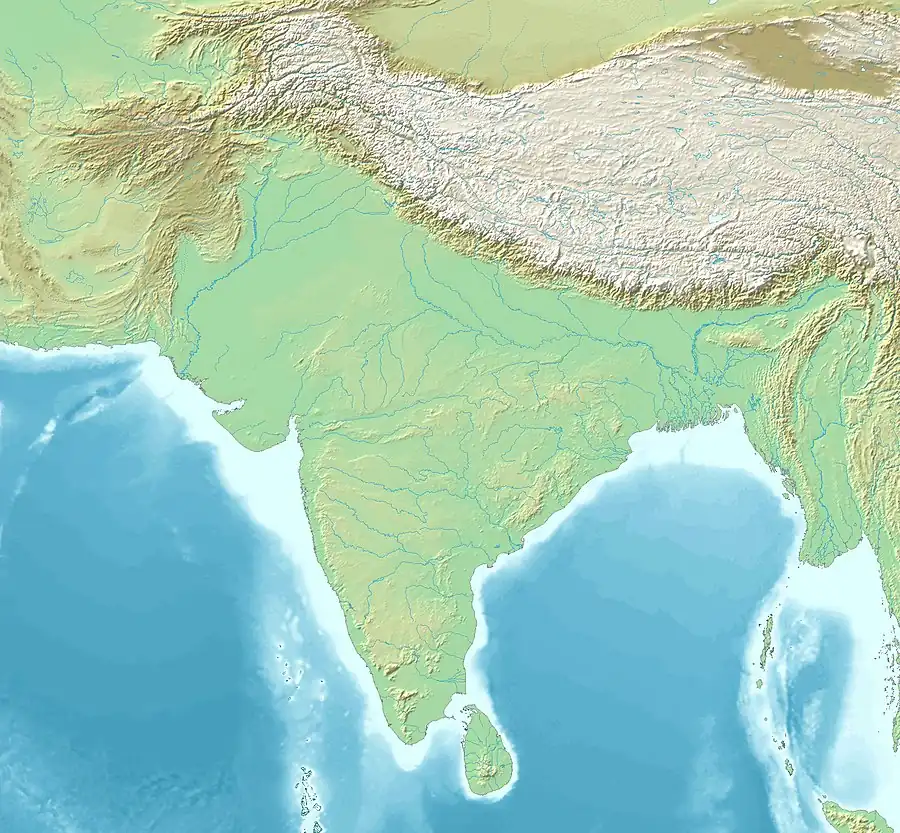

◁ Location of Dimasa kingdom around 1500 CE | |||||||||

| Status | Historical kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Dimapur Maibong Khaspur (near present-day Silchar) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Dimasa | ||||||||

| Government | Tribal hereditary monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval India | ||||||||

• Established | 13th century CE | ||||||||

• Annexed to British India | 1832 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India (Assam, Nagaland) | ||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Assam |

|---|

|

| Categories |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Assam |

|---|

|

In the 18th century, a divine Hindu origin was constructed for the rulers of the Kachari kingdom and it was named Hidimba, and the kings as Hidimbesvar.[13][14] The name Hiḍimbā continued to be used in the official records when the East India Company took over the administration of Cachar.[15]

Origins

The origin of the Dimasa Kingdom is not clear.[16] According to tradition, the Dimasa had their domain in Kamarupa and their king belonged to a lineage called Ha-tsung-tsa or Ha-cheng-sa,[17] a name first mentioned in a coin from 1520.[18] Some of them had to leave due to a political turmoil and while crossing the Brahmaputra some of them were swept away[19]—therefore, they are called Dimasa ("Son-of-the-big-river"). The similarity in Dimasa traditions and religious beliefs with those of the Chutiya kingdom supports this tradition of initial unity and then divergence.[20] Linguistic studies too point to a close association between the Dimasa language and the Moran language that was alive till the beginning of the 20th-century, suggesting that the Dimasa kingdom had an eastern Assam presence before the advent of the Ahoms.[21] The eastern Assam origin of the Dimasas is further reinforced by the tradition of the tetulary goddess Kecaikhati whose primary shrine was around Sadiya;[22] the tribal goddess common to many Kachari peoples:[23] as the Rabhas, Morans,[24][25] Tiwas, Koch,[26] Chutias,[27] etc.

According to legend Hachengsa (or Hasengcha) was an extraordinary boy brought up by a tiger and a tigress in a forest near Dimapur who replaced the existing king following divine oracles; which likely indicates the emergence of a strong military leader able to consolidate power.[28] Subsequently, the Hasengcha Sengfang (clan) emerged and beginning with Khorapha (1520 in Dimapur),[29] the Dimasa kings continued to draw lineage from Hachengcha in Maibong and Khaspur till the 19th century.[30]

Given different traditions and legends, the only reliable sources of the early history of the Dimasa kingdom is that given in the Buranjis, even though they are primarily narrations of wars between the Ahom and the Dimasa polities.[31]

Early history

The historical accounts of the Dimasas begin with mentions in Ahom chronicles: according to an account in a Buranji, the first Ahom king Sukaphaa (r. 1228–1268) encountered a Kachari group in the Tirap region (currently in Arunachal Pradesh), who informed him that they along with their chief had to leave a place called Mohung (salt springs) losing it to the Nagas and that they were settled near the Dikhou river. This supports a tradition that the eastern boundary of the Kachari domain extended up to Mohong or Namdang river (near Joypur, Assam) beyond the river Dichang, before the arrival of Ahoms.[32] Given the settlement was large, Sukaphaa decided not to engage with them before settling with the Barahi and Moran polities. During the reign of Sukaphaa's successor Suteuphaa (r. 1268–1281) the Ahoms negotiated with this group of the Dimasa, who had been in the region between Dikhou and Namdang for about three generations by then, and the Dimasa group moved to the west of the Dikhou river.[33][34] These isolated early accounts of the Dimasas suggest that they controlled the region between the Dikhu river in the east and the Kolong river in the west and included the Dhansiri valley and the north Cachar hills from the late 13th century.[35][36][37]

At Dimapur

The Ahom language Buranjis call the Dimasa kings khun timisa, and place them initially in Dimapur,[38] where Timisa is a corruption of Dimasa.[39] The Dimasa kingdom did not record their history, and much of the early information come from other sources. The Ahom Buranjis, for instance, record that in 1490 the Ahom king Suhenphaa (1488-93) created a forward post at Tangsu and when the Dimasas killed the commander and 120 men the Ahoms sued for peace by offering a princess to the Dimasa king along with other presents,[40][41][42] but the name of the Dimasa king is not known. The Dimasas thus recovered the region east of the Dikhau river that it had lost in the late 13th century.[43]

Ekasarana biographies of Sankardeva written after his death use the name Kachari for the Dimasa people and the kingdom[44] and record that around 1516 the Baro-Bhuyans at Alipukhuri came into conflict with their Kachari neighbors which escalated into the Dimasa king preparing to attack them. This led Sankardeva and his group to abandon the region for good.[45] One of the earliest mention of Kachari is found in the Bhagavat of Sankardev in the section composed during the later part of his life in the Koch kingdom where he uses it synonymously with Kirata.[46] Another early mention of the name Kachari comes from Kacharir Niyam (Rules of the Kacharis), composed during the reign of Tamradhwaj Narayan (r. 1697–1708?), when the Dimasa rulers were still ruling in Maibang.[47]

A coin dated 1520 commemorating a decisive victory over enemies is one of the earliest direct evidence of the historical kingdom.[48] Since no conflict with the Kacharis is mentioned in the Ahom Buranjis it is conjectured that the enemy could have been the nascent Koch kingdom of Biswa Singha.[49] Though issued in a Sanksritised name of the king (Viravijay Narayan, identified with Khorapha) with the mention of a goddess Chandi,[50] there is no mention of the King's lineage but a mention of Hachengsa, a Boro-Garo name indicated that an appropriate Kshatriya lineage had still not been created by 1520.[51] The first Hindu coin from the Brahmaputra valley, it followed the same weights and measures of the coins from the Muslim Sultans of Bengal and Tripura and indicate influence from them.[52]

This kingdom might have been part of ancient Sinitic networks such as the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).[53]

Fall of Dimapur

Soon after absorbing the Chutia kingdom in 1523 Suhungmung,[54] the Ahom king, decided to recover the territory the Ahoms had lost in 1490 to the Dimasa kingdom[55] and sent his commander Kan-Seng in 1526 who advanced up to Marangi.[56] In one of these attacks the Dimasa king Khorapha was killed,[57] and Khunkhara, his brother, came to power.[58] The two kingdoms made peace and decided to maintain the Dhansiri river as the boundary.[59][60] This peace did not hold and fighting broke out between an advancing Ahom force against a Kachari force arrayed along the Dhansiri—the Kacharis were successful initially, but they suffered a massive loss at Marangi, and again an uneasy stalemate prevailed.[61] In 1531 the Ahoms went on the offence and Khunkhara's brother Detcha lost his life attacking the newly erected Ahom fort at Marangi. Both the Ahom king and the commander then attacked the Nenguriya fort, and Khunkhara had to flee with his son. The Ahoms force under Kan-Seng then reached Dimapur following which Detchung, a son of the earlier king Khorapha, approached Suhungmung at Nenguriya and submitted his claim to the Dimasa throne.[62][63] The Ahoms thereafter claimed the Dimasa king as thapita-sanchita (established and preserved),[64] and the Dimasa kingdom provided support to the Ahom kingdom when it was under the attack of Turbak in 1532/1533, a Turko-Afghan commander from Bengal.[65]

But when Detchung (also called Dersongpha) tried to throw off the yoke Suhungmung advanced against Detchung captured and killed him, and then advanced on and occupied Dimapur in 1536. The Dimasas rulers thereafter abandoned Dimapur.[66]

Cultural affinities at Dimapur

.jpg.webp)

The current ruins at Dimapur, the same city that Suhungmung occupied, include a 2 mile long brick wall on three sides, with the Dhansiri river on the fourth; and tanks—indicating a large city.[67] The existing gateway too was in brick and display the Islamic architectural style of Bengal.[68] The ruins include curious carved 12 feet tall pillars of sandstone with hemispherical tops and foliated carvings with representations of animals and birds but no humans that display no Hindu influence.[69] Despite the Sanskrit markings of the 1520 silver coin issued by Viravijay Narayan (Khorapha), the city lacked any sign of Brahminical influence, from the observations in 1536 as recorded in the Buranjis, as well as the colonial observations of 1874.[70]

At Maibang

The fall of Dimapur in 1536 was followed by a 22-year period of interregnum, and there is no mention of a king in the records. In either 1558 or 1559 a son of Detsung, Madanakumara, assumed the throne with the name Nirbhaya Narayana,[71] and established his capital at Maibang in the North Cachar hills.[72] Not all the Kachari people accompanied the rulers from Dimapur to Maibong—and those who remained in the plains developed independently in language and customs.[73] In the hills around Maibong, the Dimasa rulers encountered already established Naga and Kuki peoples, who accepted the Dimasa rule.[74]

Khorapha, the earlier king, claimed in the coin issued earlier in 1520 from Dimapur that he had defeated the enemies of Hachengsa without specifying his relationship to him but Nirbhaya Narayana and his successors in Maibong for the next hundred years or so claimed in their coins that they belonged to the family of Hachensa;[75] thereby signalling a change in the mode of legitimacy from deed to birth.[76] On the other hand Dimasa kings from Maibang are recorded as Lord of Heremba from the 16th century by those outside the Dimasa kingdom who practiced sedentary agriculture and who had already experienced Brahminism.[77][78]

Koch invasion

After subjugating the Ahoms in 1564, the Koch commander Chilarai advanced on Marangi, subjugated Dimarua and finally advanced on the Dimasa kingdom, then possibly under Durlabh Narayan or his predecessor Nirbhay Narayan and made it into a feudatory of the Koch kingdom.[79] This campaign realigned the relationships and rearranged the territorial controls among the political formations of the time. Dimarua, which was a feudatory of the Dimasa kingdom, was set up by Chilarai was a buffer against the Jaintia kingdom.[80] The hold of the Ahom kingdom, which was already subjugated, over the Dimasa kingdom weakened. Further, Chilarai defeated and killed the Twipra king, and occupied the Cachar region from him and established Koch administration there at Brahmapur (Khaspur) under his brother Kamal Narayan[81]—this region was to form the core of the Dimasa rule in the 18th century. The size of the annual tribute— seventy thousand rupees, one thousand gold mohurs and sixty elephants[79]— testifies to the resourcefulness of the Kachari state.

A conflict with the Jaintia Kingdom over the region of Dimarua led to a battle, in which the Jaintias suffered defeat. After the death of Jaintia king Dhan Manik, Satrudaman the Dimasa king, installed Jasa Manik on the throne of Jaintia Kingdom, who manipulated events to bring the Dimasa Kacharis into conflict with the Ahoms once again in 1618. Satrudaman, the most Dimasa powerful king, ruled over Dimarua in Nagaon district, North Cachar, Dhansiri valley, plains of Cachar and parts of eastern Sylhet. After his conquest of Sylhet, he struck coins in his name.

By the reign of Birdarpan Narayan (reign around 1644), the Dimasa rule had withdrawn completely from the Dhansiri valley and it reverted to a jungle forming a barrier between the kingdom and the Ahom kingdom.[82]

When a successor king, Tamradhwaj, declared independence, the Ahom king Rudra Singha deputed 2 of his generals to invade Maibong with over 71,000 troops, and destroyed its forts in 1706. Tamardhwaj fled to Jaintia Kingdom where he got treacherously imprisoned by the King of Jaintia Kingdom, after his imprisonment he sent messengers to the Assam king for help, in response Rudra Singha deputed his generals with over 43,000 troops to invade Jaintia kingdom. The Jaintia king was captured and taken to the court of Rudra Singha where the Jaintia king submitted and the territories of the Dimasa Kingdom and Jaintia kingdom got annexed to the Ahom kingdom.[83]

State structure

Kacharis had three ruling clans (semfongs): Bodosa (an old historical clan), Thaosengsa (the clan to which the kings belonged), and Hasyungsa (to which the kings relatives belonged).[84]

The king at Maibang was assisted in his state duties by a council of ministers (Patra and Bhandari), led by a chief called Barbhandari. These and other state offices were manned by people of the Dimasa group, who were not necessarily Hinduized. There were about 40 clans called Sengphong of the Dimasa people, each of which sent a representative to the royal assembly called Mel, a powerful institution that could elect a king. The representatives sat in the Mel mandap (Council Hall) according to the status of the Sengphong and which provided a counterfoil to royal powers.

Over time, the Sengphongs developed a hierarchical structure with five royal Sengphongs though most of the kings belonged to the Hacengha (Hasnusa) clan. Some of the clans provided specialized services to the state ministers, ambassadors, storekeepers, court writers, and other bureaucrats and ultimately developed into professional groups, e.g. Songyasa (king's cooks), Nablaisa (fishermen).

By the 17th century, the Dimasa Kachari rule extended into the plains of Cachar. The plains people did not participate in the courts of the Dimasa Kachari king directly. They were organized according to khels, and the king provided justice and collected revenue via an official called the Uzir. Though the plains people did not participate in the Dimasa Kachari royal court, the Dharmadhi guru and other Brahmins in the court cast a considerable influence, especially with the beginning of the 18th century.

At Khaspur

In the medieval era, after the fall of Kamarupa kingdom the region of Khaspur was originally a part of the Tripura Kingdom, which was taken over by Koch king Chilarai in the 16th century.[85] The region was ruled by a tributary ruler, Kamalnarayana, the brother of king Chilarai. Around 18th century Bhima Singha, the last Koch ruler of Khaspur, didn't have any male heir. His daughter, Kanchani, married Laxmichandra, the Dimasa prince of Maibang kingdom. And once the last Koch king Bhima Singha died the Dimasas migrated to Khaspur, thus merging the two kingdoms into one as Kachari kingdom under the king Gopichandranarayan, as the control of the Khaspur kingdom went to the ruler of the Maibong kingdom as inheritance from the royal marriage and established their capital in Khaspur, near present-day Silchar. The independent rule of the Khaspur's Koch rulers ended in 1745 when it merged with the Kachari kingdom.[85] Khaspur is a corrupted form of the word Kochpur.[86] Gopichandranarayan (r.1745-1757), Harichandra (r.1757-1772) and Laxmichandra (r.1772-1773) were brothers and ruled the kingdom in succession. In 1790, a formal act of conversion took place and Gopichandranarayan and his brother Laxmichandranarayan were proclaimed to be Hindus of the Kshatriya caste.[87]

During the reign of Krishnachandra (1790 - 1813), a number of Moamarias rebels took shelter in the Cachar state. The Ahoms blamed the Dimasa for providing refuge to the rebels and this led to a number of small skirmishes between the Ahoms and the Dimasas from 1803 to 1805.[88]

The King of Manipur sought the help of Krishna Chandra Dwaja Narayan Hasnu Kachari against the Burmese Army. The King Krishna Chandra defeated Burmese in the war and in lieu was offered the Manipuri Princess Induprabha.[89] As he was already married to Rani Chandraprabha, he asked the princess to be married to his younger brother Govinda Chandra Hasnu.

Sanskritization

The fictitious but widely believed legend that was constructed by the Hindu Brahmins at Khaspur goes as follows:[90] During their exile, the Pandavas came to the Kachari Kingdom where Bhima fell in love with Hidimbi (sister of Hidimba). Bhima married princess Hidimbi according to the Gandharva system and a son was born to princess Hidimbi, named Ghatotkacha. He ruled the Kachari Kingdom for many decades. Thereafter, kings of his lineage ruled over the vast land of the "Dilao" river ( which translates to "long river" in English), now known as Brahmaputra River for centuries until 4th century AD.

British occupation

The Dimasa Kachari kingdom came under Burmese occupation in the late early 19th-century along with the Ahom kingdom. The last king, Govinda Chandra Hasnu, was restored by the British after the Yandabo Treaty in 1826, but he was unable to subjugate Senapati Tularam who ruled the hilly regions. Senapati Tularam Thaosen domain was Mahur River and the Naga Hills in the south, the Doyang River on the west, the Dhansiri River on the east and Jamuna and Doyang in the north. In 1830, Govinda Chandra Hasnu died. In 1832, Senapoti Tularam Thaosen was pensioned off and his region was annexed by the British to ultimately become the North Cachar district; and in 1833, Govinda Chandra's domain was also annexed to become the Cachar district.[91]

After Raja Govinda Chandra

In The British annexed the Dimasa Kachari Kingdom under the doctrine of lapse. At the time of British annexation, the kingdom consisted of parts of Nagaon and Karbi Anglong; North Cachar (Dima Hasao), Cachar and the Jiri frontier of Manipur.

Rulers and Kings

| Capital | King | Date of Accession | Reign in Progress | End of reign |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimapur | Mahamanipha | |||

| Manipha | ||||

| Ladapha | ||||

| Khorapha (Viravijay Narayana?) | 1520? | 1526 | ||

| Khuntara | 1526 | 1531 | ||

| Detsung/Dersung | 1531 | 1536 | ||

| Interregnum? | ||||

| Maibong | Nirbhay Narayan | 1558? | 1559 | |

| Durlabh Narayan | ||||

| Megha Narayan | 1568 | 1578 | 1583? | |

| Yasho Narayan (Satrudaman) | 1583? | 1601 | ||

| Indrapratap Narayan | 1601 | 1610 | ||

| Nar Narayan | ||||

| Bhimdarpa Narayan | 1618? | |||

| Indraballabh Narayan | 1628 | 1644? | ||

| Birdarpa Narayan | 1644? | 1681 | ||

| Garurdhwaj Narayan | 1681 | 1695 | ||

| Makardhwaj Narayan | 1695 | |||

| Udayaditya | ||||

| Tamradhwaj Narayan | 1706 | 1708 | ||

| Suradarpa Narayan | 1708 | |||

| Harischandra Narayan -1 | 1721 | |||

| Kirtichandra Narayan | 1736 | |||

| Sandikhari Narayan alias Ram Chandra | 1736 | |||

| Khaspur | Harischandra-2 | 1771 | ||

| Lakshmichandra Narayan | 1772 | |||

| Krishnachandra Narayan | 1790 | 1813 | ||

| Govindachandra Narayan | 1814 | 1819 | ||

| Chaurajit Singh (Manipur) | 1819 | 1823 | ||

| Gambhir Singh (Manipur) | 1823 | 1824 | ||

| Govindachandra Narayan | 1824 | 1830 | ||

| British Annexation | 1832 |

Notes

- "639 Identifier Documentation: aho – ISO 639-3". SIL International (formerly known as the Summer Institute of Linguistics). SIL International. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

Ahom [aho]

- "Population by Religious Communities". Census India – 2001. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved 2019-07-01.

Census Data Finder/C Series/Population by Religious Communities

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

2011census/C-01/DDW00C-01 MDDS.XLS

- "In the 13th century the Dimasa kingdom extended along the south bank of the Brahmputra, from Dikhou to Kallang and included the Dhansiri Valley and the North Cachar Hills, with its capital at Dimapur." (Bhattacharjee 1987:222)

- All the possibilities of the Kachari kingdom at Sadiya or some other places of Northeast India remain unproven theories until concrete evidence is provided. Therefore, as a term denoting this particular social group, I prefer Dimasa to Kachari in the following discussion.(Shin 2020:64)

- (Shin 2020:61)

- "In the 13th century the Dimasa kingdom extended along the south bank of the Brahmputra, from Dikhou to Kallang and included the Dhansiri Valley and the North Cachar Hills."; "During 16th to 18th century AD they established a State of their own which covered modern South Assam (Barak Valley, parts of Assam Valley and intervening North Cachar Hills) and some parts of Nagaland and Manipur." (Bhattacharjee 1987:222)

- "Dimasa conceive of themselves as the rulers and subjects of the Dimasa kingdom." (Ramirez 2007:93)

- "During the 13th-16th centuries, while these continued to represent the rule over older peasant settlements in western and central Assam, there emerged alongside them also new kingdoms from several tribal bases, then undergoing a process of politico-economic transformation. These kingdoms did not represent mere dynastic changes in an ongoing political sobiety. Rather, they were almost new state formations in a seemingly political vacuum. The Chutiya, Ahom, Dimasa, Jaintia and Koch states were such formations." (Guha 1983:10)

- (Banerjee 1990:69)

- (Banerjee 1990:91)

- "Ahom chronicals attest the existence of "Timisa kings" (khun-timisa) who ruled over a large area of middle Assam, initially from Dimapur on the western foothills of present-day Nagaland." (Ramirez 2007:93)

- (Chatterji 1951:123–124)

- "An important change in the Dimasa political tradition occurred in the mideighteenth century, probably 1745, 1750 or 1755, when the centre of administration was moved from Maibong to Khaspur in the plains of Cachar.87 From this time onwards, the Dimasa rulers used the title ‘the Lord of Heḍamba’ in their own records." (Shin 2020:70)

- (Shin 2020:69f) "The name Hiḍimbā continued to be used in the official records when the East India Company took over the administration of Cachar. This is clear from a seal of the Superintendent of the District of Cachar of 1835. See Gait, Report on the Progress of Historical Research in Assam, p. 10.

- (Bhattacharjee 1992:392–393)

- "(T)he Kacharis of North Cachar believe that they once ruled in Kamarupa and their royal family traced its descent from the Rajas of that country, from the line of Ha-tsung-tsa." (Baruah 1986:187–188)

- "[the coin struck by Vīravijayanārāyaṇa, dated 1442 Śaka (1520 ad)] bears the legend describing the king as ‘a worshipper at the feet of the goddess Chandī and a subduer of the foes of Hāchengsā’."(Shin 2020:63)

- "The tradition current among the Dimasas of Cachar mention their kingdom in ancient Kamarupa and how during a political turmoil they had to cross the big river (Brahmaputra; Dilao) and a large section of their people were washed away." (Bhattacharjee 1992:392–393)

- "(That the Chutiyas and Sadiyal Kacharis were identical) is also supported by the similarities in traditions and religious beliefs associated with both the tribes." (Baruah 1986:187)

- "(B)y demonstrating that these people spoke a Dimasa dialect, we also show that a large part of Upper Assam spoke ancient Dimasa." (Jaquesson 2017:108)

- "There is at Sadiya a shrine of Kechai Khaiti the tutelar deity of the Kacharis, which the Dimasa rulers continued to worship even after the establishment of their rule in Cachar." (Bhattacharjee 1992:393)

- Kechai Khati worshipped by Bodo-kacharis

- Rabhas worship Kechai-khati and celebrate the Kechai-khati festival once every year

- Kechai-khati festival of Rabhas

- The Tiwas, as well as the Koch, also worshipped Kechai Kati. The Koch general Gohain Kamal built temples dedicated to Kesai Khati in Khaspur for the Dehans who were Tiwa and Mech soldiers from Gobha, Nellie and Kabi.

- Kechai-khati worship of Chutias

- (Shin 2020:63–64)

- " The very first example comes from the coin struck by Vīravijayanārāyaṇa, dated 1442 Śaka (1520 ad). It bears the legend describing the king as ‘a worshipper at the feet of the goddess Chandī and a subduer of the foes of Hāchengsā’. Vīravijayanārāyaṇa is a name apparently unrecorded in other sources, but Rhodes considers that it was probably the Sanskrit name adopted by Dimasa king Khorapha, who was killed during the Ahom invasion in 1526." (Shin 2020:63)

- (Shin 2020:64)

- "As Gait pointed out, the only trustworthy information regarding the early history of the Dimasas is contained in the Ahom chronicles, though the details are almost confined to a narrative of wars." (Shin 2020:62)

- (Baruah 1986:188)

- "(P)robably in the reign of the second Ahom king Sutepha (1268–81), the outlying Dimasa settlements, east of the Dikhu river, withdrew before the advance of the Ahoms." (Shin 2020:62)

- (Phukan 1992:56–57)

- "[T]he only trustworthy information regarding the early history of the Dimasas is contained in the Ahom chronicles, though the details are almost confined to a narrative of wars. A reading from these records suggests that the sphere of Dimasa influence in the thirteenth century seemed to extend from the Dikhu river to the Kallang river and also include the Dhansiri valley and the north Cachar hills." (Shin 2020:62)

- (Bhattacharjee 1987:222)

- (Rhodes 1986:157)

- "Ahom chronicles attest the existence of "Timisa kings" (khun timisa), who ruled over a large area of Middle Assam, initially from Dimapur on the Western foothills of present-day Nagaland. They were driven by the Ahom towards the south to their present habitat where in 1540 they founded the Hedamba kingdom." (Ramirez 2007:93)

- "They were known to the Ahoms as Timisa, clearly a corruption of Dimasa." (Baruah 1986:187)

- "In 1490 during the reign of Suhenphaa (1488-93), there was a conflict with the Dimasa Kacharis, but the Ahoms sued for peace by offering a princess to the Kachari king." (Baruah 1986:227)

- "(I)t was not until about 1490 that specific conflicts between the Ahoms and the Kacharis are recorded. In that year an Ahom army, sent by King Suchangpha, was defeated on the banks of the river Dikhu. The Ahom king then offered a girl, two elephants and twelve slaves to the Kacharis, to induce them to make peace." (Rhodes 1986:157)

- (Phukan 1992:57)

- "The Kacharis, who had ceded the tract east of the Dikhau river upto the Namdang during the reign of Suteupha was, had recovered their lost possessions at the end of the 15th century, when Suteupha (1488-95) was on the Ahom throne." (Baruah 1986:231)

- Daityari mentions the aggressors were Kacharis. Ramananda mentions Kachari or Kirata. The Bordowa-carita and the Katha-Guru-Carit mention Kachari. See the footnote at (Neog 1980:69f)

- "The few Kachari families, who lived on the outskirts of the Bhuyan lands, often let their cattle roam into the latter's crop and lay it in waste. The Bhuyans invited the Kacharis to a feast as a subterfuge and killed a number of them. The Kachari ruler heard of this and prepared to fight with the Bhuyans. These chiefs approached Sankara for advice, and he asked them speedily to retreat to the north bank of the Brahmaputra." (Neog 1980:69)

- Sankardev provides a list of people in Assam who were outside the pale of Hinduism at that time in Book II of his Bhagavad Purana. "In this list the terms Kuvaca and Mleca possibly point to the Koches and Mechs, while Kirata and Kachari are synonymous, and both together are meant to include the Kacharis and others of the Mongoloid group." (Neog 1980:74–75)

- "One of the earliest references is found in the Kacharir Niyam or the Rule of Kacharis which is the codes of administration introduced by king Tamradhvajanārāyaṇa (1697–708?)." (Shin 2020:61)

- "In the absence of any Dimasa chronicles until the eighteenth century, coins and inscriptions constitute their early historical sources which provide important information about genealogical claims revealing a political process. The very first example comes from the coin struck by Vīravijayanārāyaṇa, dated 1442 Śaka (1520 ad)." (Shin 2020:62–63)

- "The Ahom military chronicles, but there is no record of any defeat by the Kacharis in 1520. However, as described above, the Cooch Beharis were consolidating and expanding their territory eastwards just at this time and these events are not well recorded in their chronicles, so that this first Kachari coin may commemorate a decisive victory that stopped Cooch Behar from expnading further to the east." (Rhodes 1986:158)

- "The legend on this coin reads: (Obv) Śrī Śrī Vī/ra Vijaya Nā/rāyana Chandī Charana Parā-/1442 (Rev) -yana Hā/chengsā Śa/tru Mardana de/va 1424." See Rhodes and Bose, A History of Dimasa Kacharis, p. 14. (Shin 2020:63f)

- "Even the king may not have acquired any appropriate kshatriya genealogy in the early sixteenth century. Hāchengsā, referred to as the ancestor of king Vīravijayanārāyaṇa in the coin, is unquestionably a Bodo name which is not found in Epic and Puranic traditions. (Shin 2020:63)

- "In any case this piece is the first coin known to have been struck by any of the Hindu rulers of Brahmaputra valley. Presumably, the Kacharis took the idea of coinage from the Muslim sultans of Bengal and the Hindu rulers of Tripura, and it is not surprising to find the same standard was used." (Rhodes 1986:158)

- Mukherjee, Rila (2011). Pelagic Passageways: The Northern Bay of Bengal Before Colonialism. Primus Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-93-80607-20-7.

- (Baruah 1986:185)

- (Baruah 1986:188)

- (Phukan 1992:57)

- "Kachari King Khorapha who was killed during an Ahom attack in 1526..." (Rhodes 1986:158)

- (Bhattacharjee 1987b:180)

- "(The Ahoms) adopted conciliatory approach and the Kacharis readily agreed...the Kacharis withdrew to the west of the Dhansiri and the Ahoms became the master of the territory between the Dikhow and the Dhansiri..." (Phukan 1992:57)

- (Bhattacharjee 1987b:178)

- (Phukan 1992:58)

- (Phukan 1992:58)

- "Khunkhara fled with his son, and a prince called Detsung was installed as king in his place. The new king gave his sister in marriage to the Ahom king along with presents, including an elephant, 500 rolls of cloth, 1,000 napkins, 100 doolies, and Rs. 1,000 in cash." (Rhodes 1986:158)

- "Suhummong proclaimed Detchung as the Raja of the Kacharis and advised him to be loyal to himself and his descendants. Henceforth the Kachari kings were termed as thepita-sanchita (established and preserved)." (Phukan 1992:58)

- (Sarkar 1992b:139)

- (Phukan 1992:58)

- "The ruins of Dimapur, which include a brick wall of the aggregate length of nearly 2 miles and 2 tanks about 300 yards square, are indicative of a city of considerable size." (Shin 2020:63)

- "The curved battlement of the gateway, as well as the ponted arch over the entrance, pointed distinctly to the Bengali style of Mohammadan architecture." (Description from Gait) (Bhattacharjee 1987:179)

- (Bhattacharjee 1987:179–180)

- "However, no clear trace of temples and images in the Dimapur ruins raises doubt about the scale and intensity of Brahmanisation in the early history of the Dimasas...But no Brahmanical temples or images are mentioned in this Buranji record, a silence which continues in the site description of 1874 as well." (Shin 2020:63)

- (Rhodes 1986:158)

- "Nirbhayanārāyaṇa (1559–63), the son of Dersongpha who led the Dimasas to Maibong, the new capital, located on the bank of the Mahur river in the north Cachar hills." (Shin 2020:64)

- "As a result of numerous changes of habitation area due to their pursuit by the Ahoms, the Kacharis split up into a number of separate groups, which later on came to be considered as independent tribes. Thus some of the Kacharis became alienated from the raja and settled in the plains, so that, gradually, differences in language and customs sprang up between them and the Kacharis of the hills." (Maretina 2011:341)

- "Independent local tribes, i.e., the Nagas and the Kukis, became subjected to the raja, taxes in whose favor were levied upon their households." (Maretina 2011:341)

- "The epithet, 'the one born to the Hāchengsā lineage', became a well-established tradition of Dimasa rulers for almost a hundred years, according to the legends of the coins issued by Meghanārāyaṇa (1566–83), Yaśonārāyaṇa (1583–601), Indrapratāpanārāyaṇa (1601–10), Naranārāyaṇa (1610–?), Darpabhīmanārāyaṇa (?–1637) and Vīradarpanārāyaṇa (1643–?); and the two stone inscriptions issued by Meghanārāyaṇa on the occasion of the erection of the gateway in Maibong in 1576." (Shin 2020:64)

- "The earlier legend, describing Vīravijayanārāyaṇa as the destroyer of enemies of Hāchengsā (hāchengsā-śatru-mardana-deva), emphasises a ruler’s successful military action, whereas the legend hāchengsā-vaṃśaja stresses his genealogy. The strategy for legitimising the authority of a king seems to have changed from deed to birth." (Shin 2020:64)

- "Keeping these aspects of their genealogical claims in mind, the title 'the Lord of Heḍamba' (heḍambādhipati) seemed to be first applied to the Dimasa kings by others, presumably the people living in the area where sedentary agriculture and Brahmanical expansion proceeded in earlier periods." (Shin 2020:66)

- "Though it is not known exactly when they came to earn this title, certainly by the sixteenth century, other people dwelling on plains called them the Lord of Heḍamba." (Shin 2020:64–65)

- (Sarkar 1992:83)

- "After the successful Assam campaign in 1564 Nara Narayan and Chilarai first advanced via Morang (i.e. Marangi) to Demera (Dimarua). Its Raja Pantheshwar, a feudatory of the Kacharis, sought Koch protection from their oppressions or depredations, became a feudatory of Nara Narayan and was appointed warden of the marches in the south against Jaintia." (Sarkar 1992:83)

- "Chilarai made an administrative centre at Brahmapur, later known as Khaspur, in order to maintain diplomatic relations with the adjoining states and for the collection of tributes. Kamalnarayan, popularly known as Gosain Kamal...was appointed the governor of Kachar who was called the first Dewan Raja. (Nath 1989:60–61)

- "By this time the Kacharis had completely withdrawn from the Dhansiri Valley, which had reverted into the jungle, forming a natural barrier between the Ahoms and the Kacharis. The Ahoms still, however, regarded the Kacharis as being a subsidiary nation." (Rhodes 1986:164)

- "...but when the next king, Tamradhvaja, boldly proclaimed his independence, the Ahom King Rudra Singha invaded Kachar in December 1706. Tamradhvaja could offer little resistance, and Maibong was soon occupied and its fort demolished."(Rhodes 1986:165)

- "Those Kachari clans which were most closely connected with the raja and his entourage were the first to rise to dominant positions. They were the Bodosa, the most senior, known as the former ruling clan; the Thaosengsa, the clan to which the ruling dynasty belonged in the period for which data are available; the Hasyungsa, the clan of the king's relatives (Crace 1930)."(Maretina 2011:343)

- "The Khaspur state originated with Chilarai's invasion in 1562 AD and remained in existence till 1745 when it merged with the Dimasa state of Maibong." (Bhattacharjee 1994:71)

- E.A. Gait (ed), Census of India, 1891, Vol. 1 (Assam), Shillong, 1892, p. 235.

- (Cantile 1980:228)

- (Nag 2018:18)

- (Nag 2018:18)

- "Thus it is clear that this is an invented tradition by the Brahman pundits in the later stage of the monarchy in the Cachar plains. Although this is fictitious, people within the community strongly believe in this story of their ancestry." (Bathari 2014:17–18)

- (Bose 1985, p. 14)

- (Rhodes 1986:167)

References

- Nag, Sajal (2018). "Devour thy Neighbour: Foreign Invasions and the Decline of States in Eighteenth Century North East India".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Cantile, Audrey (1980). CASTE AND SECT IN AN ASSAMESE VILLAGE (Ph.D.). University of London.

- Banerjee, A C (1990), "Reform and Reorganization: 1932-3", in Barpujari, H K (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. IV, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 44–76

- Baruah, S L (1986), A Comprehensive History of Assam (book), New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers

- Bathari, Uttam (2014). Memory History and polity a study of dimasa identity in colonial past and post colonial present (Ph.D.). Gauhati University. hdl:10603/115353.

- Bhattacharjee, J B (1994), "Pre-colonial Political Structure of Barak Valley", in Sangma, Milton S (ed.), Essays on North-east India: Presented in Memory of Professor V. Venkata Rao, New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company, pp. 61–85

- Bhattacharjee, J. B. (1992), "The Kachari (Dimasa) state formation", in Barpujari, H. K. (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. 2, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board, pp. 391–397

- Bhattacharjee, J. B. (1987b), "Dimasa State Formation in Cachar", in Sinha, Surajit (ed.), Tribal Polities in State Systems in Pre-colonial Eastern and North Eastern India, Calcutta: K P Bagchi and Company, pp. 177–212

- Bhattacharjee, J B (1987). "The Economic Content of the Medieval State Formation Processes among the Dimasas of North East India". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 48: 222–225. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44141683.

- Bose, Manilal (1985), Development of Administration in Assam, Assam: Concept Publishing Company

- Chatterji, S. K. (1951), "The Hidimba (Dima-sa) people", Kirata-Janakrti, The Asiatic Society, pp. 122–126

- Guha, Amalendu (December 1983), "The Ahom Political System: An Enquiry into the State Formation Process in Medieval Assam (1228-1714)", Social Scientist, 11 (12): 3–34, doi:10.2307/3516963, JSTOR 3516963

- Jaquesson, François (2017). Translated by van Breugel, Seino. "The linguistic reconstruction of the past The case of the Boro-Garo languages". Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 40 (1): 90–122. doi:10.1075/ltba.40.1.04van.

- Maretina, Sofia A. (2011), "The Kachari state: The character of early state-like formations in hill districts of Northeast India", in Claessen, Henri J. M. (ed.), The Early State, vol. 32, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 339–359, ISBN 9783110813326

- Nath, D. (1989), History of the Koch Kingdom, C. 1515-1615, Mittal Publications, ISBN 8170991099

- Neog, M (1980), Early History of the Vaisnava Faith and Movement in Assam, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass

- Phukan, J. N. (1992), "Chapter III The Tai-Ahom Power in Assam", in Barpujari, H. K. (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. II, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board, pp. 49–60

- Ramirez, Philippe (2007), "Politico-ritual variations on the Assamese fringes: Do social systems exist?", in Sadan, Mandy; Robinne., François (eds.), Social Dynamics in the Highlands of Southeast Asia Reconsidering Political Systems of Highland Burma, Boston: Brill, pp. 91–107

- Rhodes, N G (1986). "The Coinage of Kachar". The Numismatic Chronicle. 146: 155–177. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 42667461.

- Sarkar, J. N. (1992), "Early Rulers of Koch Bihar", in Barpujari, H. K. (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. 2, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board, pp. 69–89

- Sarkar, J. N. (1992b), "Assam and her pre-Mughal Invaders", in Barpujari, H. K. (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. 2, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board, pp. 127–142

- Shin, Jae-Eun (2020). "Descending from demons, ascending to kshatriyas: Genealogical claims and political process in pre-modern Northeast India, The Chutiyas and the Dimasas". The Indian Economic and Social History Review. 57 (1): 49–75. doi:10.1177/0019464619894134. S2CID 213213265.