Bilen language

The Bilen language (ብሊና b(ɨ)lina or ብሊን b(ɨ)lin) is spoken by the Bilen people in and around the city of Keren in Eritrea. It is the only Agaw (Central Cushitic) language spoken in Eritrea. It is spoken by about 116,000 people.[1]

| Bilen | |

|---|---|

| Blin | |

| ብሊና, ብሊን | |

| Native to | Eritrea |

| Region | Anseba Region, Keren |

| Ethnicity | Bilen people |

Native speakers | 120,000 (2020)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Geʽez script | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | byn |

| ISO 639-3 | byn |

| Glottolog | bili1260 |

| ELP | Bilen |

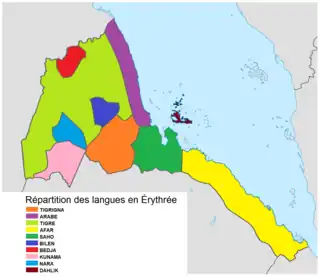

Linguistic map of Eritrea; Bilen is spoken in the dark blue region | |

Spelling of the name

"Blin" is the English spelling preferred by native speakers, but Bilin and Bilen are also commonly used. Bilin is the reference name arbitrarily used in the current initial English editions of ISO 639-3, but Blin is also listed as an equivalent name without preference. In the English list of ISO 639-2, Blin is listed in first position in both English and French lists, when Bilin is listed as an alternate name in the English list, and Bilen is the alternate name in the French list. The Ethnologue report lists Bilen as the preferred name, but also Bogo, Bogos, Bilayn, Bilin, Balen, Beleni, Belen, Bilein, Bileno, North Agaw as alternative names.

Phonology

It is not clear if Bilen has tone. It may have pitch accent (Fallon 2004) as prominent syllables always have a high tone, but not all words have such a syllable.

Consonants

Note: /tʃ/ is found in loans, and the status of /ʔ/ as a phoneme is uncertain.

/r/ is typically realised as a tap when it is medial and a trill when it is in final position.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palato- (alveolar) |

Velar | Pharyn- geal |

Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | |||||||

| Plosive / Affricate |

voiceless | t | (tʃ) | k | kʷ | (ʔ) | ||

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | ɡ | ɡʷ | |||

| ejective | tʼ | tʃʼ | kʼ | kʷʼ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ŋʷ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | xʷ | ħ | h |

| voiced | z | ʕ | ||||||

| Rhotic | r | |||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||

Fallon (2001, 2004) notes intervocalic lenition, such as /b/ → [β]; syncope, as in the name of the language, /bɨlín/ → [blín]; debuccalization with secondary articulation preserved, as in /dérekʷʼa/ → [dɛ́rɛʔʷa] 'mud for bricks'. Intriguingly, the ejectives have voiced allophones, which according to Fallon (2004) "provides an important empirical precedent" for one of the more criticized aspects of the glottalic theory of Indo-European. For example,

| Ejective consonant | Voiced allophone | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| /laħátʃʼɨna/ | [laħádʒɨna] | 'to bark' |

| /kʼaratʃʼna/ | [kʼaradʒna] | 'to cut' |

| /kʷʼakʷʼito/ | [ɡʷaʔʷito] | 'he was afraid' |

Writing system

Geʽez abugida

A writing system for Bilen was first developed by missionaries who used the Geʽez abugida and the first text was published in 1882. Although the Geʽez script is usually used for Semitic languages, the phonemes of Bilen are very similar (7 vowels, labiovelar and ejective consonants). The script therefore requires only a slight modification (the addition of consonants for ŋ and ŋʷ) to make it suitable for Bilen. Some of the additional symbols required to write Bilen with this script are in the "Ethiopic Extended" Unicode range rather than the "Ethiopic" range.

| IPA | e | u | i | a | ie | ɨ/- | o | ʷe | ʷi | ʷa | ʷie | ʷɨ/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | ሀ | ሁ | ሂ | ሃ | ሄ | ህ | ሆ | ||||||

| l | ለ | ሉ | ሊ | ላ | ሌ | ል | ሎ | ||||||

| ħ | ሐ | ሑ | ሒ | ሓ | ሔ | ሕ | ሖ | ||||||

| m | መ | ሙ | ሚ | ማ | ሜ | ም | ሞ | ||||||

| s | ሰ | ሱ | ሲ | ሳ | ሴ | ስ | ሶ | ||||||

| ʃ | ሸ | ሹ | ሺ | ሻ | ሼ | ሽ | ሾ | ||||||

| r | ረ | ሩ | ሪ | ራ | ሬ | ር | ሮ | ||||||

| kʼ | ቀ | ቁ | ቂ | ቃ | ቄ | ቅ | ቆ | ቈ | ቊ | ቋ | ቌ | ቍ | |

| ʁ | ቐ | ቑ | ቒ | ቓ | ቔ | ቕ | ቖ | ቘ | ቚ | ቛ | ቜ | ቝ | |

| b | በ | ቡ | ቢ | ባ | ቤ | ብ | ቦ | ||||||

| t | ተ | ቱ | ቲ | ታ | ቴ | ት | ቶ | ||||||

| n | ነ | ኑ | ኒ | ና | ኔ | ን | ኖ | ||||||

| ʔ | አ | ኡ | ኢ | ኣ | ኤ | እ | ኦ | ||||||

| k | ከ | ኩ | ኪ | ካ | ኬ | ክ | ኮ | ኰ | ኲ | ኳ | ኴ | ኵ | |

| x | ኸ | ኹ | ኺ | ኻ | ኼ | ኽ | ኾ | ዀ | ዂ | ዃ | ዄ | ዅ | |

| w | ወ | ዉ | ዊ | ዋ | ዌ | ው | ዎ | ||||||

| ʕ | ዐ | ዑ | ዒ | ዓ | ዔ | ዕ | ዖ | ||||||

| j | የ | ዩ | ዪ | ያ | ዬ | ይ | ዮ | ||||||

| d | ደ | ዱ | ዲ | ዳ | ዴ | ድ | ዶ | ||||||

| dʒ | ጀ | ጁ | ጂ | ጃ | ጄ | ጅ | ጆ | ||||||

| ɡ | ገ | ጉ | ጊ | ጋ | ጌ | ግ | ጎ | ጐ | ጒ | ጓ | ጔ | ጕ | |

| ŋ | ጘ | ጙ | ጚ | ጛ | ጜ | ጝ | ጞ | ⶓ | ⶔ | ጟ | ⶕ | ⶖ | |

| tʼ | ጠ | ጡ | ጢ | ጣ | ጤ | ጥ | ጦ | ||||||

| tʃʼ | ጨ | ጩ | ጪ | ጫ | ጬ | ጭ | ጮ | ||||||

| f | ፈ | ፉ | ፊ | ፋ | ፌ | ፍ | ፎ | ||||||

| z | ዘ | ዙ | ዚ | ዛ | ዜ | ዝ | ዞ | ||||||

| ʒ | ዠ | ዡ | ዢ | ዣ | ዤ | ዥ | ዦ | ||||||

| tʃ | ቸ | ቹ | ቺ | ቻ | ቼ | ች | ቾ | ||||||

| ɲ | ኘ | ኙ | ኚ | ኛ | ኜ | ኝ | ኞ | ||||||

| sʼ | ጸ | ጹ | ጺ | ጻ | ጼ | ጽ | ጾ | ||||||

| pʼ | ጰ | ጱ | ጲ | ጳ | ጴ | ጵ | ጶ | ||||||

| p | ፐ | ፑ | ፒ | ፓ | ፔ | ፕ | ፖ | ||||||

| v | ቨ | ቩ | ቪ | ቫ | ቬ | ቭ | ቮ | ||||||

| IPA | e | u | i | a | ie | ɨ/- | o | ʷe | ʷi | ʷa | ʷie | ʷɨ/- | |

Latin alphabet

In 1985 the Eritrean People's Liberation Front decided to use the Latin script for Bilen and all other non-Semitic languages in Eritrea. This was largely a political decision: the Geʽez script is associated with Christianity because of its liturgical use. The Latin alphabet is seen as being more neutral and secular. In 1993 the government set up a committee to standardize the Bilen language and the Latin-based orthography. "This overturned a 110-year tradition of writing Blin in Ethiopic script." (Fallon, Bilen Orthography [2])

As of 1997, the alphabetic order was:

- e, u, i, a, é, o, b, c, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, q, r, s, t, v, w, x, y, z, ñ, ñw, th, ch, sh, kh, kw, khw, qw, gw.

Their values are similar to the IPA apart from the following:

| Letter | Value |

|---|---|

| é | ɨ |

| c | ʕ |

| j | dʒ |

| q | kʼ |

| x | ħ |

| y | j |

| ñ | ŋ |

| th | tʼ |

| ch | tʃʼ |

| sh | ʃ |

| kh | x |

See also

References

- Bilen at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- Paul D. Fallon (18 September 2006). "Blin Orthography: A History and an Assessment" (PDF). Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- Consonant Mutation and Reduplication in Blin Singulars and Plurals

- Language, Education, and Public Policy in Eritrea Archived 2010-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). "Ethiopic Writing". The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 573. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- "Some Standardization of Blin Writing" (PDF). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Principles and Specification for Mnemonic Ethiopic Keyboards" (PDF). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

External links

Further reading

- David L. Appleyard. 2007. "Bilin Morphology". In Alan S. Kaye (ed.), Morphologies of Asia and Africa. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns (pp. 481–504).

- Paul Fallon. 2001. "Some phonological processes in Bilin". In Simpso (ed.), Proceedings of the 27th annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Paul Fallon. 2004. "The best is not good enough". In Akinlabi & Adesola (eds), Proceedings: 4th World Congress of African Linguistics

- F.R. Palmer. 1957. "The Verb in Bilin," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 19:131-159.

- F.R. Palmer. 1958. "The Noun in Bilin," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 21:376-391.

- F.R. Palmer. 1965. "Bilin 'to be' and 'to have'." African Language Studies 6:101-111.

- Leo Reinisch. 1882. Die Bilin-Sprache in Nordost-Afrika. Sitzungsberichte der phil.-hist. Classe der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, vol. 99; Vienna: Carl Gerold's Sohn.

- Leo Reinisch. 1883. Texte der Bilin Sprache. Leipzig: Grieben.

- Leo Reinisch. 1884. Wörterbuch der Bilin-Sprache. Vienna: Alfred Hölder.

- A.N. Tucker & M.A. Bryan. 1966. Linguistic Analyses: The Non-Bantu Languages of North-Eastern Africa. London: Oxford University Press.