Boom (sailing)

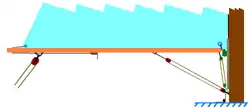

In sailing, a boom is a spar (pole), along the foot of a fore and aft rigged sail, that greatly improves control of the angle and shape of the sail. The primary action of the boom is to keep the foot flatter when the sail angle is away from the centerline of the boat. The boom also serves as an attachment point for more sophisticated control lines. Because of the improved sail control it is rare to find a non-headsail without a boom, but lateen sails, for instance, are loose-footed. In some modern applications, the sail is rolled up into the boom for storage or reefing (shortening sail).

.svg.png.webp)

Boom attachment

The forward end of the boom attaches to a mast just below the sail, with a joint called the gooseneck. The gooseneck pivots allowing the other end of the boom to move freely. The clew (back corner) of the sail attaches to the free end of the boom. The entire foot of the sail may be attached to the boom or just the clew. If the foot is not attached to the boom, the rig is known as loose footed.

A boom may be found on small headsails. There the forward end of the boom is attached to the same stay as the sail's luff (forward edge).

Lines on the boom

The control lines (ropes) on the boom act in conjunction with the halyard and leech line to ensure that the sail is trimmed most effectively.

Two primary sail control lines are attached to every boom:

- The outhaul runs from the clew of the sail to the free end of the boom. Hauling in on (tightening) the outhaul increases foot tension in the main sail. Modern loose footed sails are cut so that the outhaul is also able to pull the clew downwards towards the boom.

- The sheet is attached midway along the boom or at the free end, typically by means of a block. The block is typically attached to the boom by means of a bail, which is a U-shaped piece of metal, flattened at the ends to allow attachment with screws or rivets. In smaller boats such as dinghies it is used to control the angle of the sail to the wind on each point of sail. On largest boats this function is largely assumed by the traveller and the main sheet is used to adjust the twist of the sail to present the luff of the sail to the wind all of the way up the mast. Easing the main sheet increases twist and the twist is usually adjusted so that the aft end of the top batten in the main sail runs parallel to the boom. The traveller is a track running from one side of the boat to the other upon which sits a car to which the other end of the sheet is attached. Moving the car from side to side alters the angle of the boom to the centreline of the boat while minimising the effect on the twist of the sail.

A boom will frequently have these additional sail control lines attached:

- A downhaul may be attached to the boom near the gooseneck to pull the boom down and increase tension on the luff (forward edge) of the sail. If no downhaul is present, the gooseneck is usually fixed vertically to the mast and a cunningham may be used to control luff tension.

- The boom vang, kicking strap or kicker is an intricate set of pulleys (and, on yachts, a hydraulic ram) running diagonally between the boom and the lower portion of the mast. The kicker pulls the boom downwards. When the boat is running away from the wind the sheet will be fully eased and so the kicker becomes the primary means of controlling sail twist.

- The preventer, prevents the boom from jibing. This line is run from a point on the boom to a point forward such as a deck cleat or the base of a stanchion. Ideally, the preventer should run from the aft end of the boom to a turning block at or very close to the bow and then back to a cleat convenient to the cockpit. The line does not take tremendous force if used properly, but it prevents the boom from starting a jibe if the wind shifts or the boat rolls. Sophisticated form of preventer is a boom brake, which not only prevents unwanted jibes, but allows a slow measured jibe by modulating the tension on the brake.

- Reef Lines, are used to tie-off excess sail, when sails are reefed (shortened). Some modern systems known as "jiffy reefing" or "slab reefing" have permanent lines running through the boom for purposes of reefing. Pulling on these lines helps to gather the excess sail at the bottom of the boom, and to secure the reef points to the fore and aft of the boom. With a well designed system sailors can reef the sails without leaving the cockpit.

Other lines that may be found on a boom include:

- A topping lift, holds up the free end of the boom when the sail is lowered.

- Lazy jacks guide the sail onto the top of the boom for furling when the sail is lowered.

Boom material and hardware

Traditionally booms, and other spars, were made of wood. Classic wooden hulled sailboats, both old and new, will usually have wooden spars. When aluminium became available, it was adopted for sailboat spars. Aluminium spars are lighter and stronger than their wooden counterpart, require less maintenance and generally hold up better to marine conditions. Aluminium spars are usually associated with fibreglass boats, although one can still find a few early fibreglass hulled yachts that were equipped with wooden spars. On very large sailing vessels, the spars may be steel. Modern, high performance, racing yachts may have spars constructed of more expensive materials, such as carbon fibre.

Various hardware is found attached to the boom. The hardware could include fairleads, blocks, block tracks, and cleats. For attachment, screws are used on wooden booms and screws or rivets on aluminium booms. If the foot of the sail is attached to the boom, there may be hoops from the foot of the sail, around the boom, or there may be a track on the top of the boom into which fittings on the foot of the sail are slid.

In-boom furling

There are quite a few variations of in-boom furling available. Generally the boom is hollow with a spindle in the center upon which the sail is rolled (furled). The techniques for turning the spindle vary, but frequently a line is used to spin the spindle and recover or reef the sail. In most cases the sail can be full battened and has virtually infinite reefing options. Some sailors consider this approach safer than in-mast furling, since the sail can be lowered and flaked in the traditional method, in the case of mechanical failure. In most applications, the sail can be lowered or reefed from the cockpit. Most designs will not accommodate a loose-footed mainsail.

Boom safety concerns

The second leading cause of death on sailboats is directly attributed to the use of booms.[1] Booms can cause injuries directly, sweep people overboard, and their associated hardware and lines represent tripping hazards. On larger boats, sailors tend to stand on the boom to perform sail maintenance and install or take off sail covers. Falls from the boom onto the deck below occur. Even when stationary, booms represent a hazard since on most boats there is insufficient headroom to walk below them without ducking. According to a German study, "boom strikes were the most common cause of sailing injury overall".[2]

When boom injuries occur far from shore they can require expensive rescues. In 2010 the US Coast Guard and Air National Guard utilized a Lockheed C-130 Hercules aircraft to rescue a man from 1400 miles off the Mexican coast.[3] Deaths and injuries can occur on boats operating upon lakes and coastal waters.[4][5][6][7]

As a precaution, any sailboat with a low boom should mandate use of life jackets, and ensure others know how to obtain assistance and operate the craft. In Boston a sailor knocked overboard by the boom died in full sight of the land and other boats and the person left aboard didn't know how to use the radio.[8]

New boat designs to lower boom risks

To address the dangers associated with the boom, some designers have raised the boom higher off the deck or applied padding. However, these raise the center of gravity and increase the chances of capsizing and turtling.[9][10]

Some designers have addressed the issue by eliminating the boom completely. Classic types of sail like the square rig or the standing lugsail have always worked without booms. Modern alternatives without a boom are the mast aft rig.

Other boom uses

On an open cockpit sailboat at a mooring, a tarpaulin may be run over the boom and tied to the rails to form a tent over the cockpit.

In certain situations on larger boats, the boom can be used as a crane to help lift heavy items like a dinghy aboard.

Other boom types

Flexible boom

When the foot of a sail is attached along its whole length to a boom, the stiffness of the boom tends to hold the lower part of the sail flat.[11][12] However, the greatest aerodynamic efficiency of the sail is created when the sail is allowed to curve into an airfoil-like shape.[11][12] A flexible boom bends with the sail to create this greater efficiency.

Park Avenue boom

A "Park Avenue" boom allows for the same aerodynamic curvature as a flexible boom, but is a rigid construction with a flat surface on top.[11][13] Instead of being fastened directly to the boom, the foot of the sail is fastened to fittings that slot into grooves that run transversely across the boom.[11][13] As these fittings move within their grooves, the foot of the sail is free to curve.[11][13] It takes its name from the great width of such a boom fitted to the yacht Enterprise for the 1930 America's Cup competition, a hyperbolic comparison to the width of Park Avenue.[11][14]

See also

Bibliography

- Dear, Ian (2004). Enterprise to Endeavour: the J-Class Yachts. London: Adlard Coles Nautical.

- Vanderbilt, Harold Stirling (1931). Enterprise: The Story of the Defense of the America's Cup in 1930. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

References

- Andrew Nathanson; Glenn Hebel. "Sailing Injuries". Archived from the original on September 28, 2011.

- Tator, Charles H. (December 27, 2008). Catastrophic injuries in sports and recreation: causes and prevention: A Canadian Study. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division. p. 143. ISBN 978-0802089670.

- "Sailor Injured In Accidental Gibe Rescued In Pacific". Blue Water Sailing. May 16, 2010. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- Richardson, Tom (June 30 – September 9, 2010). "Coast Guard Airlifts Injured Man from Sailboat off Nantucket Coast Guard Airlifts Injured Man from Sailboat off Nantucket". New England Boating. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- "Man hit by sailboat boom, critically injured".

- "Attorney Advertisement Seeking Clients Owing To Boom Injuries". Friedman & Bonebrake. Archived from the original on December 22, 2010.

- Lochhaas, Tom (May 20, 2010). "The Importance Of The Boom Preventer". Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- "Passenger/Crew Orientation". BoatSafe.com. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- "US Sailing Keelboat Course - Design and Stability". Archived from the original on November 27, 2010.

- "Discussion thread on height of boom above deck". Yachting and Boating World Forums. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- Dear 2004, p.67

- Vanderbilt 1931, p.162

- Vanderbilt 1931, p.163

- Vanderbilt 1931, p.164

Further reading

- Rousmaniere, John (June 1998). The Illustrated Dictionary of Boating Terms: 2000 Essential Terms for Sailors and Powerboaters (Paperback). W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 174. ISBN 0393339181. ISBN 978-0393339185