Bosansko Primorje

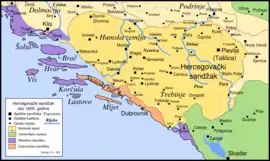

Bosansko Primorje, (transl. Bosnian Coast, or Bosnian Littoral), is a historical coastal region on the eastern Adriatic shores, which between the beginning of the 14th and the end of the 17th century stretched from the Neretva river delta to Kuril area of Petrovo Selo, near today's Dubrovnik, above Mokošica in Rijeka Dubrovačka. This region is referred in historiography as the Bosansko Primorje, Bosnian Littoral or Bosnian Coast.

Bosansko Primorje as historical region, which comprised entire Primorje Župa, was changing over time in scope and territorial area. It was mentioned in historical documents from the period of the beginning of the 14th century until the end of the 19th century. Since then, the related term Bosanskohercegovačko primorje has been in use.

Geographical description and history

This area included all coastal areas between Herceg-Novi and the Neretva river delta.[1] This region in context of socio-political and territorial existence of the country, in all its iterations starting with Bosnia, Ottoman Bosnia, and Austro-Hungarian Bosnia and Herzegovina, to modern times (including Banate, Kingdom, Ottoman era, Austro-Hungarian rule, first and second Yugoslavia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina) will be gradually reduced, starting with the end of the 14th century onward, and today comprises only a narrow stretch around the coastal town of Neum and its hinterland.[2]

Early history

In the 6th century Pelješac came under Byzantine rule. Upon the arrival of the Slavs to the area from the Neretva river to Rijeka Dubrovačka, and from the northern Herzegovina mountains to the Adriatic coast, new socio-political entities had been established, namely Narentines, Travunia and Zachlumia, and ruled by newly risen local nobility. Ston with Rat (modern days name is Pelješac) and Mljet were under the rule of one of these principalities, namely under the knyazs of Zahumlje. These local rulers acknowledged the supremacy of Byzantium. After Mihajlo Višević, who acknowledged the authority of Bulgarian emperor Simeon, Zahumlje was ruled over by different dynasties. Around 950, it was briefly ruled by Prince Časlav. At the end of the 10th century, Samuilo was the Lord of Zahumlje, and the principality belonged to king Ivan Vladimir. In 1168, the Principality of Zahumlje were conquered by Rascian Grand Župan, Stefan Nemanja. Thirty years later, Zahumlje was invaded by Andrew, the King Hungary. In 1254, Béla IV of Hungary invaded Bosnia and Zahumlje. By 1304, Zahumlje was conquered by Pavao I Bribirski of Šubić family and ruled by Mladen II until family's fall in 1322. Then for a short period between 1322 and 1325 area is ruled by local župan, and from 1325 by Stjepan II Kotromanić. Republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), acquired it from Bosnian rulers in several purchases over several decades, first in 1333 and then on 15 January 1399. King Tvrtko II confirmed purchase part of the Bosansko Primorje to Dubrovnik on 24 June 1405.

The old Ston was located on the slopes of the hills of Gorica and St. Michael, south of the Ston field. There were several early Christian churches there, the largest of which was St. Stephen's Church. The bishopric church of Mary Magdalene stood until it was bombed by the Allies in 1944. The only church that still remains is the church of St. Michael, built in the middle of the late antique castrum.

The original old town was demolished in the earthquake of 1252. With the arrival of the Republic, a new city was built on today's location. When renovations were made at the church of St. Michael at the top of the hill, fragments of Roman decorative plaster, Roman tombstones and antique ceramics were found, confirming this assumption. According to some sources, Ston experienced a destructive civil war in 1250, and in these conflicts the city suffered a great deal of destruction.

Bosansko Primorje in medieval times

From the annexation of medieval Zahumlje in 1321, that will henceforth be called Humska Zemlja (transl. Land of Hum),

Historian specialists in Bosnian medieval times, usually describe the coastal area which stretches from the mouth of the Neretva River to the Kurilo (Petrovo Selo, Dubrovnik), and call it the Bosansko Primorje (transl. Bosnian Littoral, or Bosnian Coast). This area was from the 10th to the beginning of the 14th century in the hands of the Zahumlje's knezs. When the people of Ragusa bought Ston and Stonski Rat in 1333, these newly acquired estates were not safe for them, so they sought to secure them by purchasing the area from Ston to Kuril from the Bosnian state on January 15, 1399. (Lj. Stojanović, Old Serbian Charters and Letters, I, No. 429; Dr. Gregor Ćremošnik, Sale of the Bosnian Coast to Dubrovnik in 1399 and the King of Ostoja, Gl. ZM, 1928, pp. 109–126). King Tvrtko II confirmed this part of the Bosnian Coast to the people of Ragusa on June 24, 1405. (Lj. Stojanović, Old Serbian charters and letters, I, no. 513). When the Ragusans came into possession of the Bosnian Coast, they called it "Terrae Novae", and declared that the pastures there are the common property of the entire population of the Republic and applied their statute to that territory.

The turbulent times at the beginning of the 14th century spread across the entire country of Zahumlje. The usurpation by the Branivojević brothers, forced the people of Dubrovnik to fight them in 1326 with the help of Stjepan II Kotromanić. That year, people from Dubrovnik settled Ston, and immediately began to invest and rebuild, and established a new Ston to defend the Pelješac and protect the slaves from which they had earned big revenue. Since the conflict between the Ban in Bosnia and Serbian king, the Dubrovniks purchased Pelješac with Ston from both rulers in 1333.

Ottoman era

After the Ottoman conquest of Bosnian Kingdom, renamed as Herzegovina (transl. Herzog's land), until the conclusion of the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), the Bosansko Primorje included two sub-regions, the southeastern between Dubrovnik and Herceg-Novi, and northwestern between Dubrovnik and Brštanik fort in the Neretva river delta near Neum-Klek. The northern part stretched from the mouth of the river Cetina to the mouth of the river Neretva, while the southern part included the coastal belt from the old parish of Dracevica to Risan, with Herceg-Novi as the most important place. Between those two parts of the coast is the territory of the Republic of Dubrovnik. During the First Morean War (1684-1699), the largest part of the Bosnia and Herzegovina coast was conquered by the Republic of Venice.[3] According to the provisions of the Treaty of Karlowitz from 1699, those areas were officially separated from the Herzegovinian Sanjak and joined to Venetian Dalmatia. After that, the Bosnia and Herzegovina coast was reduced to two very narrow strips: around Neum in the north and around Sutorina in the south.

Those two areas were not attached to Venetian Dalmatia, thanks to the Republic of Dubrovnik, which did not want to have a direct territorial contact with the Venetian Republic, and therefore ceded Neum to the Ottoman Herzegovinian Sanjak.[4]

Aftermath

As the last remnants, Neum and Sutorina remained under Ottoman rule until 1878, when they fell under the Austro-Hungarian occupation.

After the end of World War II in the 1940s, in a secret agreement between two leading members within the branches of the Communist Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, Sutorina was given away to the newly created federal unit of Montenegro. Only Neum permanently remained part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as the last stretch of the medieval Bosansko primorije, and later Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina littoral. The term today is Bosanskohercegovačko primorje.

Legacy

Since 1377 and the establishment of Bosnia as a kingdom, the Bosansko Primorje has been included in the Bosnian royal title, which was a practice of using intitulation template from Byzantines via the Serbian kings.[5][6]

The memory of the former Bosnian, and later Herzegovinian, littoral has been preserved in the official name of the Serbian Orthodox Eparchy of Zahum-Herzegovina and Littoral.[7]

See also

References

- Ćirković 1964b.

- Halimović Dženana (2014-11-20). "Čija je Sutorina? [Whose Sutorina is?]". Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Bosnian and Serbo-Croatian). Radio Free Europa (Radio Slobodna Evropa). Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- Jačov 1990.

- Stanojević 1970.

- Dautović & Dedić 2016, pp. 233, 234.

- Miller 1921, p. 511.

- "Istorija — Srpska pravoslavna eparhija zahumsko-hercegovačka i primorska". eparhija-zahumskohercegovacka.com (in Serbian). Retrieved 3 May 2023.

Bibliography

- Dautović, Dženan; Dedić, Enes (2016). "The Royal Charter of king Tvrtko I Kotromanić issued to the Ragusan commune (Žrnovnice, 10th April 1378 – Trstivnica, 17th June 1378)". Godišnjak Centra za balkanološka ispitivanja (45): 225–246. doi:10.5644/Godisnjak.CBI.ANUBiH-45.79. ISSN 2232-7770. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- Atanasovski, Veljan (1979). Pad Hercegovine. Beograd: Istorijski institut.

- Jačov, Marko (1990). Srbi u mletačko-turskim ratovima u XVII veku. Zemun: Sveti arhijerejski sinod Srpske pravoslavne crkve.

- Stanojević, Gligor (1970). Jugoslovenske zemlje u mletačko-turskim ratovima XVI-XVIII vijeka. Beograd: Istorijski institut.

- Ćirković, Sima (1964a). Istorija srednjovekovne bosanske države. Beograd: Srpska književna zadruga.

- Ćirković, Sima (1964b). Herceg Stefan Vukčić-Kosača i njegovo doba. Beograd: Naučno delo.

- Ćirković, Sima (1964c). "Sugubi venac: Prilog istoriji kraljevstva u Bosni". Zbornik Filozofskog fakulteta u Beogradu. 8 (1): 343–370.

- Šabanović, Hazim (1959). Bosanski pašaluk: Postanak i upravna podjela. Sarajevo: Naučno društvo Bosne i Hercegovine.

- Miller, William (1921). Essays On The Latin Orient. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 3 May 2023.