Branchial cleft cyst

A branchial cleft cyst or simply branchial cyst is a cyst as a swelling in the upper part of neck anterior to sternocleidomastoid. It can, but does not necessarily, have an opening to the skin surface, called a fistula. The cause is usually a developmental abnormality arising in the early prenatal period, typically failure of obliteration of the second, third, and fourth branchial cleft, i.e. failure of fusion of the second branchial arches and epicardial ridge in lower part of the neck. Branchial cleft cysts account for almost 20% of neck masses in children.[1] Less commonly, the cysts can develop from the first, third, or fourth clefts, and their location and the location of associated fistulas differs accordingly.

| Branchial cyst | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Branchial arch fistula Benign cervical lymphoepithelial cyst Pharyngeal arch cyst |

| |

| Fistulogram (sinogram) of a right branchial cleft sinus. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Painless, firm mass lateral to midline, usually anterior to the SCM, which does not move with swallowing |

| Causes | Family history |

| Differential diagnosis | Vascular anomaly, dermoid cyst, thymic cyst, lymphadenopathy, lymphoma, HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer |

| Treatment | Conservative, surgical excision |

Symptoms and signs

Most branchial cleft cysts present in late childhood or early adulthood as a solitary, painless mass, which went previously unnoticed, that has now become infected (typically after an upper respiratory tract infection). Fistulas, if present, are asymptomatic until infection arises.[2]

Pathophysiology

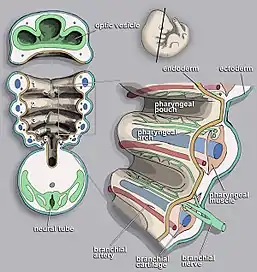

Branchial cleft cysts are remnants of embryonic development and result from a failure of obliteration of one of the branchial clefts, which are homologous to the structures in fish that develop into gills.[3][4]

Pathology

The cyst wall is composed of squamous epithelium (90%), columnar cells with or without cilia, or a mixture of both, with lymphoid infiltrate, often with prominent germinal centers and few subcapsular lymph sinuses. The cyst is typically surrounded by lymphoid tissue that has attenuated or absent overlying epithelium due to inflammatory changes.[5] The cyst may or may not contain granular and keratinaceous cellular debris. Cholesterol crystals may be found in the fluid extracted from a branchial cyst.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of branchial cleft cysts is typically done clinically due to their relatively consistent location in the neck, typically anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. For masses presenting in adulthood, the presumption should be a malignancy until proven otherwise, since carcinomas of the tonsil, tongue base and thyroid may all present as cystic masses of the neck.[6] Unlike a thyroglossal duct cyst, when swallowing, the mass should not move up or down.[7]

Types

Four branchial clefts (also called "grooves") form during the development of a human embryo. The first cleft normally develops into the external auditory canal,[8] but the remaining three arches are obliterated and have no persistent structures in normal development. Persistence or abnormal formation of these four clefts can all result in branchial cleft cysts which may or may not drain via sinus tracts.

- First branchial cleft cysts account for 8% of the sinuses and cysts of the neck. The cysts are usually located in the front or behind the ears, lateral to the facial nerve, parallel to the external auditory canal.[9]

- Second branchial cleft cysts account for 90 to 95% of the neck cysts. It is located medial to the facial nerve, at the anterior neck, anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, above the hyoid bone. Skin pit can be found in this location. However, if skin pits are found on both sides of the neck, then, branchio-oto-renal syndrome should be ruled out. Infection of the cysts in this region can compress trachea, causing respiratory problems, or it can compress the oesophagus, causing dysphagia, and irritating the sternocleidomastoid muscle, causing torticollis.[9]

- Third and fourth branchial cleft cysts are rare, usually consisting of 2% of all branchial arch abnormalities, located below the second branchial arch. They usually have sinus tracts that start from the anterior neck at the thyroid gland until pyriform sinus posteriorly. If infected, it can cause acute infectious thyroiditis in children and if enlarge rapidly, can cause tracheal compression in children.[9]

Treatment

Conservative (i.e. no treatment), or surgical excision. With surgical excision, recurrence is common, usually due to incomplete excision. Often, the tracts of the cyst will pass near important structures, such as the internal jugular vein, carotid artery, or facial nerve, making complete excision impractical due to the high risk of complications.[10]

An alternative and less invasive treatment is ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy.[11]

See also

References

- Pincus RL (2001). "Congenital neck masses and cysts". Head & Neck Surgery - Otolaryngology (3 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 933.

- Colman R (2008). Toronto Notes. pp. OT33.

- Hong C. "Branchial cleft cyst". eMedicine.com. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- Shubin N (2009). Your Inner Fish. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-307-27745-9.

- Nahata V (2016). "Branchial Cleft Cyst". Indian Journal of Dermatology. 61 (6): 701. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.193718. PMC 5122306. PMID 27904209.

- "Differential diagnosis of a neck mass". www.uptodate.com. UpToDate. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- "Branchial Cleft Cyst". missinglink.ucsf.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-06-26. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- "Duke Embryology - Craniofacial Development". web.duke.edu. Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- Quintanilla-Dieck, Lourdes; Penn, Edward B. (December 2018). "Congenital Neck Masses". Clinics in Perinatology. 45 (4): 769–785. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2018.07.012. PMID 30396417. S2CID 53224066.

- Waldhausen JH (May 2006). "Branchial cleft and arch anomalies in children". Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 15 (2): 64–9. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2006.02.002. PMID 16616308.

- Kim J (April 2014). "Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy for benign non-thyroid cystic mass in the neck". Ultrasonography. 33 (2): 83–90. doi:10.14366/usg.13026. PMID 24936500.