Brazilian Army in the First Republic

During Brazil's First Republic (1889–1930), the Brazilian Army was one of several land-based military forces present in the country. The army was equipped and funded by the federal government, while state and local chiefs had the Public Forces ("small state armies") and irregular forces such as patriotic battalions.

The First Republic began and ended with political interventions by the army—the Proclamation of the Republic and the Revolution of 1930, respectively—and the army was additionally deployed in several internal conflicts. Profound army reforms, inspired by European standards and competition against Argentina, increased the Brazilian Army's capabilities both for war and for participation in society. The army's function was twofold: external defense and maintenance of internal order. These were reflected in its territorial distribution, concentrated mostly in Rio Grande do Sul and in the federal capital in Rio de Janeiro.

At the beginning of the First Republic the army was a small force of less than 15,000 men, organized in small battalions or equivalent isolated forces, without larger permanent units. Mobilization was difficult. Soldiers were recruited through voluntary service or forced conscription, they had no routine military training and served long "professional" careers without being incorporated into a reserve. Officers had academic education of a civilian nature at the Military School of Praia Vermelha (EMPV), the "scientists", or little to no education, the "tarimbeiros". In the violent 1890s, the army exhibited a poor performance in campaigns such as the War of Canudos, motivating reforms implemented by successive administrations in the Ministry of War from the turn of the century. The General Staff of the Army (EME) was created in 1899 to serve as the highest body, but it was not clear whether command of the army would be exercised by the Minister of War or the head of EME. A new system of coastal fortifications was built in Guanabara Bay over several decades.

The Imperial German Army became the main outside influence in 1908, under Hermes da Fonseca's War Ministry. Officers sent to train in Germany launched a movement for military reform upon their return, earning the nickname "Young Turks". Until 1921, a modern order of battle was established, with military regions, regiments, brigades and divisions, although many units were not created or were understaffed. New German weapons equipped the troops and the Vila Militar was built in Rio de Janeiro. Mandatory military service was instituted through the Sortition Law in 1908, but only during the First World War, when the importance of the Armed Forces increased, did it come into effect in 1916. Through this new mechanism, soldiers became a temporary component of the force and a constant increase in personnel was possible, which reached up to 50,000 men in 1930.

German influence gave way to the French Military Mission, hired in 1919. Sergeants gained importance at the head of the new tactical units, the combat groups, and the army acquired its first armored vehicles and aviation. Almost all equipment was imported, as the arms industry was inexpressive. In the 1920s, a new generation of officers had already emerged, professionalized at the Military School of Realengo, which succeeded the EMPV. Career progression came to depend on new or reformed schools such as the Officers Improvement School and the General Staff School. Defense plans were prepared against Argentina, which had a more modern army. Military authorities hoped that the reforms would produce officers more loyal to the hierarchy, but the result were the lieutenant revolts from the lower ranks. In the long run, the strengthening of the army's leadership and the expansion of the concept of national defense, initiated in this period, allowed for military interventions by generals that occurred later in Brazilian history, such as the 1937 coup d'état.

Background

The officers within society

The republic was established in Brazil by a coup d'état by officers dissatisfied with the civilian elite of the Empire. As these soldiers were not united, after two military governments (Deodoro da Fonseca and Floriano Peixoto) power passed to the civilian oligarchies in 1894. The Old or First Brazilian Republic, which lasted until the Revolution of 1930, was marked by the predominance of the elites of São Paulo and Minas Gerais in the country's political scene, the large autonomy of the states and coronelism in local politics. The country's economy relied on agricultural exports, with the coffee cycle reaching its peak, but industrialization and urbanization also advanced.[2]

In this context, army officers were marginalized and resentful of the civilian elite.[3] They came from the small educated portion of the population, but still from the middle strata, with no money to pay for a law or medical school for their children; some were from traditional military families. A military career was a form of social ascension. The pay was modest and, below the rank of colonel, the standard of living was outside the middle class. The low number of army soldiers from São Paulo and Minas Gerais was an indication of the divorce with the civilian elite:[4] in 1895, there were eight generals from Rio Grande do Sul, one from São Paulo and none from Minas Gerais; in 1930 there were eight from Rio Grande do Sul and none from Minas Gerais or São Paulo.[5] Officers were not apolitical: bonuses and bribes helped to co-opt senior officials, who worked politically through appointments and promotions and sometimes used their prestige to win elections.[6] The urbanization and industrialization of the period created new allies in society for officers opposed to the dominant oligarchies.[7]

The coastal towns were the origin of a large part of the officialdom. The intellectual officers who served in the cities were appalled at the conditions encountered by their colleagues sent to units in the vast interior of the country. From then on, the officers' self-image as a civilizing force was born, which would mark the presence of the State in the most remote borders of the country, transmit civic and military instruction to its populations and transform Brazil into a nation state.[8][9]

The army among the defense forces

The Brazilian Navy competed with the army due to institutional rivalries and the benefits received from those in power. Due to its distance from the proclamation of the republic, it lost priority to the army in the first republican governments. After the admirals' participation in the naval revolts, the navy was greatly weakened and only recovered after Rodrigues Alves's government (1902–1906), implicitly as a counterweight to the army. The profile of navy officers was more aristocratic, isolated and more professionally trained, making the navy more open to civilian elites.[10] The navy's political participation is lower than that of the army in the period.[11]

The army was not the only land-based military force, as local leaders and state oligarchies had their own troops.[12] On paper there were still units of the National Guard, subordinated to the Ministry of Justice, with officers formed by local political elites, whose soldiers were men under their command. It was more common for these political chiefs to arm and mobilize their peons and henchmen in "patriotic battalions", enforcing their will by force.[13]

The biggest problem was the military police (Public Forces), which prevented the Armed Forces from gaining complete internal military control. Taking advantage of the privileges of federalism, the oligarchies of the most powerful states transformed their police forces into small armies, some of which were better equipped for war than the federal army itself. The Public Force of São Paulo hired a French training mission before the Brazilian Army and maintained its own aviation. In São Paulo and other states, state troops outnumbered federal ones. These state armies secured the political power of the states and made federal intervention difficult.[14] In contrast to these forces, the federal army had national presence and interests, serving as a strong arm of the central power against regionalist tendencies.[15]

Mandatory military service made the National Guard redundant.[16] It was extinguished in 1919 and replaced by the 2nd line of the army, but this force had no effective organization and was also extinguished in 1921.[17] In 1917–1918 the Public Forces and Fire Brigades were, by agreement, considered auxiliary forces of the army, while the National Guard was considered the 2nd line of the army. For minister Caetano de Faria, a great challenge had been overcome and the army had gained control of the military forces.[18] However, the problem would only be truly resolved after 1930.[19]

The army's purpose

Operational history

The Brazilian Empire was overthrown in a bloodless military coup, but the next decade was a bloody one.[20] The greatest threat to the new regime was the Federalist Revolution of 1893–1895, when Rio Grande do Sul entered a state of civil war, which spread to Santa Catarina and Paraná and connected to the second navy revolt, which started in the capital.[21] The Federalist Revolution and the War of Canudos (1896–1897) resulted in thousands of deaths.[22]

After this period, in 1900–1902, Brazilians faced Bolivians in the Acre War, when the only missions against a neighboring country took place in the period.[23][lower-alpha 1] The army participated in the repression of the Vaccine Revolt, in 1904, but the Military School of Praia Vermelha launched a rebellion at the same time.[24] From 1912 to 1916, the Contestado War was fought, a conflict with similarities to Canudos, but which took place over a vast area.[25] Brazil declared war on Germany in 1917, joining the Allies in World War I, but only the navy went abroad.[26] The army was also called upon to intervene in some of the numerous local "civil wars" when state forces were unable to resolve them.[13]

The combat experiences of the 1890s ruined the army rather than strengthening its professionalism.[27] The army was already weakened in the last two decades of the Brazilian Empire,[28] and in the first years of the republic, its operability was sometimes inferior to that of rebels.[29] In Canudos, the army needed to mobilize 40% of its personnel[30] and send several expeditions to defeat peasants unprepared for war.[31] The officers' consensus in the early 20th century was that their force was inefficient and backward, with low budgets, poor facilities, and uneven weaponry making training and maintenance difficult.[32] Poor performance in campaigns such as Canudos and Contestado convinced the high command of the need for reforms.[31][33]

In the 1920s, a new cycle of revolts began from the lower ranks of the army, tenentism: the Copacabana Fort revolt, the 1924 uprisings in São Paulo, Sergipe, Amazonas and Rio Grande do Sul and the Prestes Column until 1927, among others.[34] Tenentism was just a revolt within the army, whose command remained loyal to the government.[35] The tenentists were only successful when they allied with Liberal Alliance politicians to overthrow the First Republic in the Revolution of 1930, inaugurating the Vargas Era.[34]

Reformist movements

For the political scientist José Murilo de Carvalho, the First Brazilian Republic was marked by "the army's intense struggle to become a national organization capable of effectively planning and executing a defense policy in its broadest sense".[36] During this process, Brazilians took European armies as a reference of modernity.[37] The military regulations were Portuguese, or adapted from Portugal, until the beginning of the 20th century,[38] and there was French and German influence since the last decades of the Brazilian Empire. The military relations market in Latin America was disputed by France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States.[39] In addition to comparing themselves to European standards, Brazilian reformists followed similar changes in the armies of Argentina and Chile,[40] preferred customers of Germany.[39]

The first years of the republic, due to its turbulence, saw only ephemeral and improvised changes. Only after the administration of João Nepomuceno de Medeiros Mallet in the Ministry of War (1898–1902) did a continuous movement of reforms in all aspects of the institution began, but budgetary resources were still scarce.[41] In 1905, general Hermes da Fonseca, commander of the 4th Military District in Rio de Janeiro, carried out the first major field maneuvers since the beginning of the republic in Santa Cruz. The repercussion in the press was great, but the serious deficiencies in material and preparation were evident, convincing Hermes of the need for radical reforms.[42][43]

German influence

Hermes da Fonseca was appointed Minister of War in the government of Afonso Pena (1906–1909), where he had in common with the Baron of Rio Branco, Minister of Foreign Affairs, a Germanophile stance. Fonseca visited Germany in 1908, watching the maneuvers of the Imperial German Army, recognized at the time for the modernity of its General Staff and war technology. He ordered military equipment and agreed to send young Brazilian officers to train in German units. In Brazil, he carried out the "Hermes Reform",[44][45] implementing, among other measures, a new order of battle to be filled out by recruits incorporated by compulsory military service.[46] However, the conscription was controversial and would take years to implement.[47] Hermes da Fonseca became president in 1910–1914, but his "Salvations Policy" discredited the army, further delaying mandatory military service.[48]

The Ministry of War changed a lot with each new government,[49] and new reforms were announced before the previous ones were effectively implemented. Discontinuity marked the process.[50] But sending lieutenants to Germany had a lasting impact: the former trainees were the first within the army to have a modern professional profile[51] and wanted a new army based on German military doctrine,[52] which they advertised through the magazine A Defesa Nacional. Their movement was a kind of professional tenentism, manifested by intellectual criticism of their hierarchical superiors, earning former interns and their sympathizers the nickname of "Young Turks".[51] Several members of this group joined the General Staff of the Army and the cabinet of Minister of War José Caetano de Faria (1914–1918), who favored reformist ideas.[52][53]

This administration coincided with World War I, considered a watershed in army history by military historian Jehovah Motta.[54] Attention was more on Europe than on Contestado; Brazilian officers watched the "two model armies, the German and the French one, test men, equipment, organization, strategies and tactics against each other".[55] The Armed Forces quickly grew in importance,[56] and the war served as a pretext to expand the force and finally implement compulsory military service.[57] The budget increased after the war, but remained a bottleneck for modernization.[58]

French influence

Assimilating the novelties of warfare in Europe was a necessity accepted by minister Caetano de Faria, but he was skeptical about the importation of a European model (even if adapted to Brazil) through a mission of foreign instructors.[59] Two countries competed to offer such a mission to Brazil, France and Germany. A German mission had been discussed since the Hermes Reform and advocated by the Young Turks, while the Francophiles also made their propaganda. The First World War left the matter on hold and, at its end, made the German mission impossible: Brazil had declared war on Germany, and after the Treaty of Versailles, France was victorious, and Germany was disarmed. Brazilian bourgeois preferred French culture, and France and the United Kingdom formed the economic axis of Europe. Interested in expanding their influence and selling surplus war materiel, the French sent military missions to several Latin American countries in the 1920s.[60][61]

Thus, in September 1919 the Brazilian government signed a contract for a French Military Instruction Mission. With 24 officers, including its first chief, general Maurice Gamelin, the mission initially received the direction of four schools (Officers' Improvement, General Staff, Intendance and Veterinary schools),[62] since the main Brazilian interest was the instruction and professionalization of its personnel.[63] The mission's role was to provide technical advice, not controlling the final decision of what would be changed,[64] but it was a top-down pressure following bottom-up pressure from the Young Turks.[65] Tensions between French instructors and Brazilian pupils were inevitable.[66] From the beginning, the French encountered resistance, such as the antipathy between Gamelin and general Bento Ribeiro, Chief of Staff of the Army.[67]

The historiography also has several criticisms of the French instructors' performance, but they effectively contributed to a modern mentality and identity of the Brazilian officers. French experience and theories were incorporated by strategic thinkers such as generals Tasso Fragoso and, in the 1930s, Góes Monteiro. The National Defense Council,[68] created in 1927 to guarantee the continuity of planning, regardless of changes in the Ministry of War, was also a result of the French mission.[49] French influence would later be supplanted by American influence after World War II.[69]

Internal and external functions

The Brazilian Constitution of 1891, in Article 14 (Title I) of the Preliminary Provisions, defined the Armed Forces as follows:[70]

The land and sea forces are national, permanent institutions, destined to the defense of the fatherland abroad, and the maintenance of the laws in the interior. The armed force is essentially obedient, within the limits of the law, to its hierarchical superiors, and obliged to uphold the constitutional institutions.

Thus, the role of the army was twofold: the "defense of the fatherland abroad", that is, an international conflict, and the "maintenance of laws in the interior", defending the government.[71][72] Officers and civilian politicians were unsure of the army's role. A European-style army would be ready for a conventional war with other countries, but the Brazilian reality was one of civil wars, rebellions and guerrillas.[37] The Canudos and Contestado wars were clear examples of the use of the army in internal order and to some extent as a police force.[73]

The dual function was visible in the distribution of troops. In 1889, 35% of the forces were in Rio Grande do Sul, a border region, 10% in Rio de Janeiro (the country's capital) and 5% in Mato Grosso, also on the border.[74] In the republic, the largest concentrations remained in Rio Grande do Sul and the Federal District, with a large number of dispersed battalions. The priorities were, on the one hand, to avoid a direct Argentine invasion or through Uruguay, and on the other, to garrison the ports and police the large population centers.[75]

Two civilian intellectuals had an influence on military thinking about the army's role in society at the time: Olavo Bilac and Alberto Torres.[76] Bilac, publicist for compulsory military service, wanted the military to approach the people and the moral transformation of the population through military service.[77] Torres did not believe in this moral transformation and feared that the permanent officer corps would become an authoritarian caste. He had a broad concept of national defense, encompassing government, education, justice, economics, foreign policy, and military force. Both intellectuals advocated national unity and the removal of the military from politics.[78]

Possible war with Argentina

The hypothetical external enemy would be Argentina,[23] whose rivalry with Brazil for hegemony in the Southern Cone led to a naval arms race. War fears reached a peak in 1908, with the "telegram No. 9" affair, encouraging militarization in both countries. In the following decades, relations were more harmonious and the ABC Pact was negotiated.[79][80] Brazilian officers wanted to match their strength with the Argentine Army, which in the 1920s was a "real and mobilizable army", militarily superior to Brazil. The Argentines received German instructors, professionalized their staff, increased their personnel and acquired war material since 1900. Against them, the "skeletal divisions" of the Brazilian Army would find it difficult to mobilize due to the inexpressive rail network (30,000 kilometers in 1921). Brazilian and Argentine officials considered the possibility of a war with each other, and the Argentines also considered Chile as a potential enemy.[81] The tensions were more based on mutual perceptions than real intentions.[23]

General Tasso Fragoso studied the topic at the General Staff of the Army and disseminated his conclusions. For him, Argentina could not dominate all of Brazil, but it would try to destroy the Brazilian Navy and invade Rio Grande do Sul. The only land route from Southeastern Brazil to Rio Grande do Sul was the São Paulo-Rio Grande Railroad, which Fragoso compared to the Trans-Siberian Railway. The invasion forces would come through the province of Corrientes. The Brazilians would need to defend the railroad, especially the Santa Maria junction, until reinforcements could arrive. The hypothesis of an Argentine invasion by Uruguay was also studied, especially by Rivera and on the Melo-Bagé axis, compromising access to the port of Rio Grande. Military exercises against an imaginary coalition, headed by Argentina, were held under the guidance of the French Military Mission in October 1921. Tasso Fragoso sought to keep the French out of the planning, as it was a matter of national security.[81][82][83] Even so, it was due to French influence that Brazil adopted a defensive posture, fearing Argentine superiority.[84]

The conflict could not be trench warfare like the Western Front of World War I; the vastness of the territory, the precariousness of the roads and the disinterest of the civilians suggested a war of movement with small and mobile units. The French Military Mission tried to adapt the French system to Brazilian conditions, but French influence ended up preparing the army for an unreal war. Brazilian officers complained about the divisional organization intended by the French, with numerous and heavy artillery, designed for a war of industrial powers with a dense rail network. To make matters worse, general Gamelin represented a static doctrine that would be defeated when he commanded the French Armed Forces in the Battle of France in 1940. European-style static warfare proved itself incapable of defeating a small, mobile force in Brazil, the Prestes Column.[85][86]

Organization

High Command

The army was represented within the government by the Minister of War. This was a political position and did not necessarily have to be occupied by a military officer, but only one civilian held the position during the period, deputy Pandiá Calógeras, from 1919 to 1922. In 1889, command of the army fell to the minister's adjutant-general, a position always occupied by soldiers. The adjutant-general had broad attributions, such as personnel management and planning, and directly commanded the garrison of the capital and state of Rio de Janeiro.[87][88] The General Adjutant Department was extinguished in 1899, giving way to the Army General Staff (EME), which had been founded in 1896, but until then it was not a reality and had no approved regulations.[32] It was not clear whether command of the army would fall to the Minister of War or the head of EME, and these two figures disputed the leadership of the institution in the following years.[89]

The EME was an umbrella body,[90] in charge of studying the organization, direction and execution of military operations, with authority over the instruction and discipline of troops in the command of forces and directions of military services.[32] Its officers were the same as the old department, and thus, too busy with bureaucratic tasks. To get around this situation, in 1908 the Hermes Reform eliminated the exclusivity of the General Staff corps, opening its tasks to officers of any branch, and freed the EME from many administrative tasks.[91] Another important change was the subordination of the Military School of Realengo to the EME in 1918, inspired by equivalent organizations in Germany.[92] The EME's role only began to become clear after the arrival of the French Military Mission.[93]

A 1915 decree assigned the supreme command of the army to the President of the Republic, with the bodies of the high command under his command: the Ministry of War, EME, Inspectorate of the Army and Grand Commands (of the Military Regions and divisions).[94][95] The Minister of War would have authority over the other bodies, centralizing the administration of the army. However, another decree in 1920 centralized the supreme direction and coordination of all army services in the EME.[94] In an ideal division of labor, the head of the EME would handle the day-to-day affairs of the army, while the Minister of War would negotiate with Congress, seek funding, and resolve other political issues. In reality, ministers tried to centralize decision-making and planning within themselves.[96] Politicians did not want to give the EME too much independence, as through the Ministry of War they could use the army as a political instrument.[97]

Land force

In 1889 army troops were divided into a number of units of the four branches: infantry battalions, cavalry regiments, field artillery regiments, fixed artillery battalions, and engineering battalions. Cavalry and artillery "regiments" were equivalent to infantry battalions.[98] The units' personnel was small: the largest, the infantry battalions, had 425 soldiers on paper.[99] The "unit" is an organization with some administrative autonomy, but not operational, as only larger structures (brigades and divisions) combined combat branches, combat support and logistical support. Western armies had standing divisions and grouped their infantry battalions into regiments.[100] The Brazilian Army only organized brigades and divisions during wartime, and thus, its organization in peacetime was quite rudimentary.[98] It was through the reforms of the period that it created an organic structure similar to that of modern armies.[40]

In the Brazilian Empire there were "Arms Commands" in the provinces, but they were territorial inspection divisions, not troop commands, and were subordinated to the province's Executive. These commands were replaced in 1891 by military districts;[101][102] this new territorial division, imitating the European divisional system, was unprecedented in subordinating the districts directly to the Ministry of War and organizing them by criteria such as operability and tactical feasibility.[103] However, they did not work well and were inadequate to the administrative demands of conscription. Therefore, military districts were replaced by permanent inspection regions in 1908,[104] and these by military regions and military districts in 1915.[95][105]

Only in 1908, with the Hermes Reform, did the structure acquire a complexity never before seen in the country. Infantry battalions were grouped into 15 regiments, and these into five Strategic Brigades, in a ternary arrangement (three regiments of three battalions); the Strategic Brigade had a "heavy" structure, similar to a division. Cavalry brigades grouped the regiments of this branch. The artillery began to have groups between the batteries and regiments. Outside the brigades were battalions and companies of caçadores (hunters),[lower-alpha 3] regiments of independent cavalry, and other units responsible for the security and defense of regions without strategic forces.[106]

The Hermes Reform's order of battle was too ambitious for the size and material conditions of the army. Many units did not exist, or were out of personnel. European armies had regiments of three thousand men; Brazil provided for regiments of just over 500 men.[107] The 11th Region and 4th Strategic Brigade used in the Contestado War were largely fictional.[108] Regiments with three battalions on paper could barely send a company to the war.[107] Later organizations would also have many "fictions".[109]

The 1915 army "remodeling" replaced the Strategic Brigades with Army Divisions, each with two brigades of two infantry regiments, a divisional cavalry regiment, and an artillery brigade. The regiments remained with three battalions. Battalions of Caçadores were incorporated into divisions. The next major reform was in 1921, under French guidance, transforming Army Divisions into Infantry Divisions and Cavalry Brigades into divisions.[110] The regimental and divisional system would undergo transformations until its extinction in the Master Plan of 1970, which instituted the brigade system used in the 21st century.[111]

Personnel

Hierarchy

In the 19th century, the hierarchy of enlisted ranks was, in ascending order, soldier, lance corporal, 2nd and 1st corporal, furir, 2nd and 1st sergeant and sergeant-adjutant. At the beginning of the republic, the ranks of lance corporal and furir were abolished and the rank of 3rd sergeant emerged. The terms "post" and "grade" were used both for corporals and sergeants and for officers in certain senses, and it was not until the mid-twentieth century that "post" would only mean the ranks of officers, and corporals and sergeants would be known as the "graduados" (NCOs).[112]

In the hierarchy, the rank of marshal was the highest. Below him, the former ranks of brigadier and field marshal were replaced by general of brigade and general of division in 1890. Ensigns ceased to exist in 1908. The aristocratic term cadet ceased to be used in 1897. In the Military School, the rank of student ensign ceased to exist in 1905, when the rank of aspiring officer appeared, considered a special soldier, with similar treatment to officers.[113]

Soldiers

At the beginning of the republic, soldiers were professionals, but only in the sense of serving for long years,[114] re-engaging until the end of their careers. Until 1916, they were incorporated by voluntary service and forced conscription.[115] In theory all soldiers were volunteers, but in reality the police arrested the "dregs of society" in the streets, who went to the barracks.[116] The population's aversion to the situation of enlisted soldiers was already old.[117] Indiscipline and riots were constant, and the officers maintained control through physical punishment.[118] There was no centralized instruction schedule, and recruits were recruited throughout the year without receiving homogeneous training.[119]

A soldier's life was one of standing guard and parading, not military training. They barely mastered the handling of weapons and drill commands. In Canudos, they showed poor aim. "If the Brazilian generals in 1900 were unprepared to lead, neither were the soldiers able to follow orders".[120] The peasants in Canudos prioritized killing army officers, knowing that their soldiers would be unwilling to fight without their leadership.[121]

Compulsory military service

Reforming recruitment had been the ambition of the Brazilian military since the Empire.[122] Hierarchical superiors insisted on compulsory military service as a way to fill the gaps in personnel, generalize military training and form mobilizable reserves,[123] transforming annual waves of recruits into soldiers and transferring them to a growing reserve.[124] They did not want to be left behind by Chile, Argentina, and Peru, which had adopted compulsory military service starting in 1900.[125] Their reference model was Europe, where conscription had been the norm since the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). European armies had large reserves, which they could quickly mobilize via the railroads and arm with their growing industries. Conscription was, along with education, a way for nation-states to transform and control their populations.[126] Thus, in Brazil it was seen by its defenders as synonymous with progress.[127]

Conscription was instituted by the Sortition Law in 1908, with strong government pressure and support from the urban middle class,[128] but much controversy. Mandatory military service clashed with the interests of rural colonels, who politically benefited from the forced recruitment practiced until then.[47] In the cities, this law met with strong anti-militarist opposition in the labor movement.[129] It was not possible to compile the recruitment lists, and thus, the lottery was not carried out.[130]

Only in December 1916 was the first military lottery held.[131] Reserve recruitment centers emerged around the same time as military service alternatives.[128] The conscription had the effect of allowing the expansion of the personnel, despite suffering from a high rate of non-compliance.[132] After 1916, the formation of reservists transformed the military career. The force was divided into permanent and variable elements, respectively consisting of career officers (with some enlisted men) and soldiers who returned to civilian life after a short period.[104] Those incorporated were younger and arrived simultaneously, facilitating the socialization essential to training and discipline.[133]

Recruits no longer represented the "dregs of society";[133] modernization demanded a higher technical level from enlisted men.[134] Still, the lower-class profile of enlisted men did not change with compulsory military service.[135] In the 1922–1923 medical records, recruits were mostly agricultural workers, laborers, and trade employees.[136]

The 1908 law provided for compulsory service from the age of 21, with two years on active duty and seven in reserve on the first line.[137] Many would serve for only one year. The new rhythm of the garrisons should be the constant training of new recruits.[133] Still, into the 1920s foreign military observers continued to have a low opinion of discipline and other aspects of the troops. The main training remained as drill commands, despite efforts to increase firing instruction.[138]

Non-commissioned officers

The ranks of corporal and sergeant were natural career progressions for soldiers. Promotions occurred within the units, maintaining strong ties between sergeants and soldiers.[139] Sergeant courses were held within the troops.[140] Specializations were obtained at the General Shooting School of Campo Grande and the Tactical and Shooting School of Rio Pardo, both transformed into Practical Schools in 1890.[141] Promotion criteria were heavily influenced by personal ties, and so sergeants depended on the favors of officers.[142] Some became officers through commissions, especially in times of war.[143]

Many sergeants had little education, and the class had very limited rights and frequent indiscipline, notably in the 1915–1916 "sergeants' revolt" conspiracy.[144] Sergeants "were generally single, lived in the barracks and had a reputation for living an unruly life", but regulations made it difficult for enlisted men to form families, and officers considered the marriage of sergeants to be an excessive financial burden on the institution.[143] The courses for sergeants had a "insufferable load of theoretical and practical knowledge".[140] The schools for training sergeants were isolated initiatives, with a reduced number.[139]

The role of sergeants was to assist officers in carrying out orders. In the 1910s, with the Young Turks' reforms, corporals and sergeants also began to receive training to train recruits. The sergeants' revolt of 1915–1916, with its exclusivist tone, revealed the group's own identity and made officers suspicious of the sergeants' loyalty. It also altered their formation: it was intended for it to be dense like that of the officers, but with a short duration. In 1919, the School of Infantry Sergeants of Vila Militar (ESI) was created, where instructors for War Shooting would be trained. The centralization and density of socialization facilitated the sergeants' self-recognition as a group.[145] In 1920, an editorial in A Defesa Nacional defended a higher educational level for sergeants, as they could no longer cope with the army's growing demands.[142] Under the influence of the French Military Mission, the army made progress in its efforts to raise the technical level of NCO's.[146] The new basic tactical units, the combat groups, required greater manpower and responsibility for sergeants .[147] On the other hand, the changes in their social status were small.[146]

Officers

The army was entirely controlled by the officers. Brazil did not develop a tradition of leadership by sergeants, as in the American, British, German and French armies. After 1916, officers were the only permanent element of the army.[148] Their education was important in the consolidation of the republican state.[149] The only entry route for the regular officer corps was the Military School,[150] but before the implementation of compulsory military service, many officers came from the lower ranks through promotion,[115] and in the 1920s, Centers for the Preparation of Reserve Officers (CPOR) emerged in some cities.[150]

In the early years of the republic, there were two types of officers, "bachelors in uniform", trained in artillery or engineering at the Military School of Praia Vermelha (EMPV), and "tarimbeiros", with minor courses in infantry and cavalry or none at all.[151] The tarimbeiros were experienced officers,[152] close to the troops' problems, but did not have modern technical training; they had practical experience.[153][154] The "bachelors" did not have this training either;[154] the curriculum had a civilian content, forming bureaucrats, writers and politicians.[155] They were unaccustomed to discipline and subordination[156] and averse to serving in troop corps, considering themselves above the task of instructing soldiers.[157] In the internal conflicts of the 1890s, tarimbeiros commanded the troops. Bachelors, with a few exceptions, were absent.[29][lower-alpha 4] Thus, the military still needed to be militarized.[158]

Reforms in military teaching

In addition to Praia Vermelha, there were two other schools in Fortaleza and Porto Alegre, but they were closed in 1898.[159] The EMPV was closed after its participation in the Vaccine Revolt in 1904. Infantry and cavalry students studied at the War School, in Porto Alegre, and the others at the Artillery and Engineering School, in Realengo; the next stage of teaching was at the Learning Schools, respectively located in Rio Pardo, for infantry and cavalry, and Santa Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, for artillery and engineering.[160] From 1905 onwards, new teaching regulations fought the civilian nature of the military teaching and scientism, reinforcing the discipline and professionalizing the curriculum.[161][162] Students were framed militarily, organized as infantry battalions. Only privates could enroll, eliminating the figure of the student officers.[163] The General Staff School (EEM) was also created for higher complementary education, training the officers who would organize the army. It would be defined later, in the 1913–1914 regulation, as an "institute of higher military studies". However, in the 1900s and 1910s it had few students and influence.[164]

Military education reform only found budgetary conditions in the 1910s.[165] The teaching of all branches was centralized in Realengo in 1913.[166] Instructors, previously chosen by favoritism, were selected by competition in 1918. This new generation of students, called the "Indigenous Mission", applied the thinking of the Young Turks.[167][168] In the curriculum, the preponderance of practical and utilitarian instruction over theory reached its peak.[169] The students were subjected to physical exercises in the Gericinó instruction field; there was no equivalent area at Praia Vermelha.[170] The heavy routine and socialization gave a strong sense of belonging to the institution and difference in relation to civilians.[171]

The Military School of Realengo trained "platoon leaders and not generals". More advanced theoretical studies were taught separately.[172] However, only with the creation of the Officers Improvement School (EsAO) in 1919 did continuous study after the Military School become a reality for most officers. This school qualified lieutenants and officers up to the command of a battalion. It was used by the French Military Mission to transmit its doctrine, as Realengo was out of its control before 1922. Field exercises were carried out with school units.[173] Officers trained at EsAO were assigned as instructors in the units to spread the doctrine.[66] From 1925, cavalry officers trained at the Cavalry School instead of EsAO.[174][175] Another place where the French worked early on was EEM. It gained central importance, as it was the school where the members of the Army High Command began to be trained. In 1919, a decree determined that after ten years (1929), the General Staff course diploma would become a prerequisite for promotion to the generalship.[176]

EsAO and EEM were training schools, with a generalist content, but under the French Military Mission, specialized schools were also created or modified.[177] The Health Service School trained military doctors from 1923; until then, the army had been served by physicians trained in civilian colleges. The Military Aviation School formed pilots, observers, mechanics and specialists for aircraft. The School of Intendance, inaugurated in 1921, had a course in military intendance and another in administration, to train management bodies. The Veterinary School started to have an improvement course in 1929. A Transmission Instruction Center operated from 1927 to 1929. Training centers also emerged with faster specialization courses: the Training Center for Riding Instructor Officers, Artillery Instruction Center and Infantry Specialists Instruction Center.[178]

Profile change

The French Military Mission disciplined the officer corps, eliminating resistance to its reforms. Large maneuvers were performed, and the deficiencies of the officers were evident. According to Francisco de Paula Cidade, "senior officers with a map of the region and a compass in their hands took the wrong path and ended up not knowing where they were". Many officers were old, and the French evaluated the Brazilian Army as inferior to the Argentine in organization, preparation and services. Those who failed in the maneuvers, dubbed "grenade shards", were counted as wounded and had to pass command. When the failure was in written works or oral tests, the officers received the "blue ticket" with an invitation to withdraw from enrollment. Even senior senior officers were eliminated.[179][180] The impact of the French was not immediate but gradual as they influenced officer training and the army's identity.[64]

One aspect of the officers' new identity was a belief in the meritocracy of their careers.[171] Since the middle of the previous century, career advancement combined "meritocratic principles (school titles, length of service, bravery) and extra-meritocratic principles (personalistic relationships, political fame)"; from the 1920s, professionalization reinforced meritocratic principles.[181] Promotions combined merit and seniority criteria; in practice, the promotion boards prioritized seniority. The generals' promotions were controlled by the president.[182] The low ranks of officers were the most numerous: in 1920, 65.1% of officers were lieutenants and 21.3% captains. They weren't necessarily young; there were many first lieutenants in their late thirties.[183] The "bottleneck" of these ranks, produced by the amnesties for revolts and the high age limits for permanence in the posts, resulted in a slow career progression, contributing to the revolts of the lower ranks.[184]

Upon assuming the Ministry of War in 1918, Pandiá Calógeras considered that the officers were more busy with bureaucracy than with missions and professional improvement. The problem persisted in reports for decades to come.[185] In the 1920s, American military observers considered the professional proficiency of Brazilian officers inferior to that of Argentine and Chilean officers, and much lower than that of Americans.[186] Still, young officers trained to European standards felt better prepared than their superiors, and indeed, the lieutenants of the 1920s were "the most technically professional rebels the army has ever faced", in the definition of historian Frank McCann.[187] For Cordeiro de Farias, his 1919 class at the Military School was the first to receive a truly military education.[188] His practical and technical knowledge, transmitted by the Indigenous Mission, was an advantage in the campaigns of the Prestes Column.[189]

Physical structure

Total personnel

In 1889 the army had 15,000 men, and could expand to 30,000 if necessary.[190] There were no reserves and it was difficult to mobilize large contingents in the early years of the republic.[119] The provisional government at the beginning of the republic doubled the troops to 24,877 men, but it was normal for the actual number of troops, especially soldiers, to be smaller.[191] The shortage of personnel was felt during the conflicts of the 1890s, requiring measures such as the recruitment of hundreds of ensigns among the civilian population, the commissioning of soldiers as officers and the mobilization of patriotic battalions. Desertion by officers and enlisted men was a problem.[29][30] The total personnel reached 28,160 in 1900,[191] but just before the Acre expedition, the financial situation caused the government to cut it to just 15,000 men. Units went on campaign with soldiers borrowed from other units, leaving gaps.[192] By 1910, the manpower had risen to 24,877 men, which was still considered insufficient for national defense,[193] and personnel shortages remained serious.[194]

The total personnel was set at 52,000 men in 1915, which did not correspond to reality.[195] U.S. military intelligence recorded an authorized strength of 43,747 men in 1919, with 37,000 in actual service.[196] Authorized strength was 42,977 men in 1921.[191] The French Military Mission suggested a peacetime reorganization of 74,354 men, but Brazilian officers did not consider the plan realistic, and Congress did not approve the plan.[lower-alpha 5] The reality was far short of that figure. There were only 24 of the planned 71 field artillery groups, and 5 of the 27 heavy artillery groups. Existing units had "glades" of personnel, which was observable in the actual availability of officers (2,551 out of 3,583 predicted) and physicians (216 out of 369 in 1920).[197]

In 1921, Jornal do Brasil published the following figures: 3,000 officers, 43,000 non-commissioned officers and soldiers, 10,000 reservists, 2,000 students in military schools and 16,000 men in the state military forces.[198] The French ambassador reported a strength of 38,527 men in 1922.[199] The 1925 personnel authorization law provided for 3,583 officers and 42,393 enlisted men; according to American estimates, the actual number would be 3,045 officers and 36,000 soldiers.[200] According to data published in 1941 by the Minister of War, Eurico Gaspar Dutra, the actual troops were 30,000 in 1920 and 50,000 in 1930.[191]

World War I and conscription provided consistent growth impetus for personnel.[114][201] In 1930 there were 1.1 soldiers per thousand inhabitants, a low rate compared to other countries, but the number of soldiers in the army had grown by 220% since 1890, while the population had grown by 162%.[201] In the long run, numerical expansion strengthened the central power to the detriment of local coronelism.[114]

Equipment

In 1889 the army used a series of imported armaments. The infantry used the Comblain rifle, some old Minié rifles, and bayonets.[202] These weapons would be used by Napoleonic or Paraguayan War-style line formations, with the platoon as the basic deployment unit and movements similar to today's parade formations. Tactical developments in Europe were not followed.[203] Cavalry used Winchester repeating carbines, fitted with Comblain cartridges, Nagant revolvers and sabers. Half of the regiments carried spears.[202][lower-alpha 6] The field artillery used La Hitte, Paixahans, Whitworth, and Krupp guns, and the coastal artillery, Parrot, Whitworth, Armstrong, and Krupp, as well as Congreve rockets.[202] Machine guns were the Nordenfelt since 1889, with two for each infantry battalion and two to four for each cavalry or field artillery regiment.[204] The predominant color of the uniforms was dark blue.[202]

German Mannlicher rifles, the Brazilian Army's first repeating rifles, began to replace Comblain rifles and carbines in 1892. In turn, they were replaced until World War I by the Mauser ones, also German.[204][lower-alpha 7] As part of the Hermes Reform, many armaments were purchased in Germany. Krupp would supply artillery: 75 and 105mm howitzers, 75mm mountain artillery, and 305mm guns for coastal artillery.[45] Danish Madsen machine guns, designated "machine gun rifle model 1906-1909" in Brazil, were distributed from 1911 onwards. The machine gun companies created by the 1908 reform used eight Maxim machine guns.[205] The number of machine guns was very small, less than 100 in 1917; at the same time the German Army had 15 thousand. The 1908 reform also changed the uniforms color to khaki, which was better for camouflage, and adopted sapping tools for the infantry.[45] Aviation was first used in 1915 for reconnaissance in the Contestado War, but Ricardo Kirk, the only army aviator at the time, was killed in a flight accident.[206]

In 1920, both the Minister of War and A Defesa Nacional described the army as practically unarmed, so serious were the material deficiencies.[207] The situation improved in that decade.[208] Submachine guns became the centerpiece of combat groups, which were the new primary tactical unit for the infantry and, to some extent, the cavalry. Fire and movement tactics, based on the French experience in World War I, were revolutionary in Brazil.[209][210] The infantry received Hotchkiss machine guns in 1922 and should still have 37mm Puteaux guns and Stokes mortars as accompanying equipment.[211][212] The common caliber of the army's guns remained the 7.92×57mm Mauser.[lower-alpha 8] The artillery received French cannons from Schneider and Saint-Chamond.[lower-alpha 9] The new French armaments had their controversies among officers, many of whom preferred models from other countries.[213] The purchase of cannons was controversial in the press, in part due to efforts by both companies to discredit each other.[214]

The army's first attempt at mechanization was the Assault Car Company, formed with eleven Renault FT-17 tanks in 1917; however, it would not continue.[215] The great technological novelty was aviation.[216] With the help of French instructors, the first class of aviators was formed in 1920. The first planes, with training, fighter, observation and bombing models, were also French.[217] They were concentrated at the Military Aviation School, in Campo dos Afonsos. The divisional organization approved in 1921 provided for twelve squadrons subordinated to the divisions, but only in the 3rd Military Region did they get off the ground. Even this expansion was short-lived: the Rio Grande do Sul Aviation Squadron Group, created in 1922, was deactivated in 1928.[218][219] In 1927 aviation became the army's fifth branch, alongside infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineering.[220] There was no Brazilian Air Force; military aviation was dispersed between army and naval aviation.[221]

Industry

The military industrial facilities at the beginning of the republic were a cartridge and war artifacts factory (Rio de Janeiro), two gunpowder factories (Rio and Mato Grosso) and three war arsenals (Rio, Rio Grande do Sul and Mato Grosso).[222] They were not armament factories,[223] which continued to be imported, with Brazilian arsenals only assembling and providing maintenance. There were some private companies in the sector, such as Rossi and the National Cartridge Factory.[224] The facilities in Mato Grosso were deactivated at the beginning of the 20th century.[lower-alpha 10] A gunpowder factory was installed in Piquete, São Paulo, in 1909. Small and medium caliber ammunition was produced at the cartridge factory, in Realengo, and at the war arsenal in Rio de Janeiro, but it was still necessary to import, especially from the United States. These few manufacturing enterprises worked with imported raw materials.[223][225]

Prior to World War I, officers had a consensus to at least produce ammunition, but the Minister of War declared in 1899 that existing arsenals were sufficient.[225] Due to the outbreak of war, not all armaments ordered in Germany were delivered.[45][223] This exposed the risks created by dependence on imports. During the war, the army command created the Directorate of War Material and sent a delegation to buy industrial machinery in the United States. In 1919, the need for autonomous production was already the official line of the Ministry of War. Brazilian officials discussed the need for base industries, especially metallurgy, the space to be occupied by the private sector and the State, and the difficulties of building a competitive industry; investments would be high and returns would be slow to arrive. These discussions were at the beginning of Brazilian industrial development from the 1930s onwards.[226] The military reformists began to demand this industrialization in their area of interest, even without contesting the agro-exporting based economy as a whole.[227]

Facilities

The precariousness of the barracks and their sanitary facilities was widespread at the beginning of the republic and would take a long time to change. In 1902 the Curitiba units were on rented property.[228] The 1918 ministerial report pointed out the lack of barracks for several units, such as the 8th Battalion of Caçadores, headquartered in small houses rented by the city hall, and the 3rd Cavalry Regiment, in low thatched huts. As minister Calógeras would later notice, there were no mobilization material storages, and the artillery ammunition stored in the magazines was enough for less than an hour of fire. There were also deficiencies in instruction fields.[229]

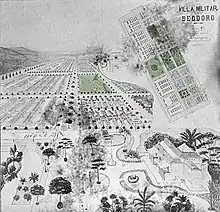

In Rio de Janeiro, military installations, some used by the army since the 18th century, were concentrated in the center and coast during the Brazilian Empire, but since 1850 there was an interiorization of the barracks, motivated by the appreciation of real estate, the need for open spaces to train new maneuvers and armaments and the defense of reserves of war material. The new barracks accompanied the expanding railroads.[230] The first significant effort to alleviate the shortage of facilities was Vila Militar, whose construction began in 1909.[228] It was positioned along the Central do Brasil Railway and adjacent to the Gericinó field, where it was possible to perform maneuvers.[231] It was part of a complex of military areas also covering Deodoro, Realengo and Campo dos Afonsos, a region still little urbanized.[232]

The Vila Militar had a barracks, office, infirmary and workshops for each regiment and individual houses for officers and sergeants.[233] It broke with the barrack building tradition of the previous century and incorporated modern principles of planning, circulation, hygiene, zoning, and standardization, as well as demonstrating the officers' place in society.[234] Hermes da Fonseca intended a base on the Vila Militar model for each strategic brigade,[233] but due to lack of funds, this model was not reproduced outside Rio de Janeiro.[235] Units in the Federal District were better housed, fed, and supplied than those in the rest of the country,[75] and it was in these that officers preferred to serve.[236]

A comprehensive program of barracks building began in the 1920s,[228] on a scale never seen before: work on 45 barracks and the construction of 61 new barracks, five military hospitals, infirmaries, five warehouses, an airport, a stadium and a pontoon training lake. In addition to remedying the deficiencies of the barracks, it was necessary to expand the structure to absorb the reservists who would be mobilized in a war. The barracks had to be away from urban centers to make room for training, which was not always possible. They were of two types: collapsible, made mainly for the cavalry, and masonry. The works were delegated to the country's private initiative, mainly the Construction Company of Santos, by Roberto Simonsen, at an estimated cost of 23 million dollars, financed by public bonds. Simonsen's company worked from 1921 to 1925. The construction program significantly improved the material conditions of the barracks, brought the Brazilian Army and State to new places and developed the infrastructure of the municipalities where it was carried out. However, it fueled new accusations of corruption against the Calógeras administration. The "Calógeras barracks" continued as the physical base of many units in the following decades.[237][238][239]

Fortifications

The naval revolt revealed the technological backwardness of the coast, unable to face enemies inside Guanabara Bay.[240] Thus, while the barracks were moved inland, the defense system on the coast of Rio de Janeiro was remodeled. Over three decades, new maritime fortifications were built with concrete and steel and old ones were given new weapons. The system had seven symmetrically distributed fortifications. The forts of Copacabana (built from 1908 to 1914) and Imbuí (from 1896 to 1901) were built outside the bay with large caliber cannons and long range (up to 23 kilometers). The old fortresses of Santa Cruz and São João and the new Fort Laje received new batteries from 1896 to 1906 to defend the entrance to the bay with short-range fire. Between 1913 and 1919, the forts of São Luís and Vigia received howitzer batteries to shoot at battleships with plunging fire.[231][241]

Modernization and politicization

Relation with tenentism

War ministers such as Fernando Setembrino de Carvalho (1922–1926) and Nestor Sezefredo dos Passos (1926–1930) supported modernization and accepted the army as a strong arm of the Brazilian political elite.[242] Influential officials in this period saw modernization, Europeanization, professionalism, legalism, and political non-intervention as synonymous.[243] The army would be the "great mute", in the French saying.[244] The reforms were intended to neutralize military revolts, forming new "professional" and "technical" officers, disconnected from politics.[245] The Young Turks' reformism is interpreted in historiography as non-interventionism (transforming the army without attacking the political and social order), an interventionism in favor of the prevailing order[246] or a modernizing and conservative interventionism, critical of the established liberal regime.[247] In any case, in the 1920s they were loyal to the government and only advocated change within the system.[248]

Loyalist behavior is what José Murilo de Carvalho attributed to the category of the "professional soldier", which he opposed to the "citizen soldier", an ideology of military interventionism developed since the Military Question, during the Brazilian Empire. Soldier would be citizens with full political rights, willing to break the hierarchy to transform society. This line of reasoning was present both in the proclamation of the republic and in tenentism. Numerous military rebellions took place in the period, none of them representing the army as a whole.[249] Paradoxically, according to the Brazilian Constitution of 1891, the military was responsible for guaranteeing the law, and at the same time, they owed obedience to superiors "within the limits of the law". The law did not spell out who a rebel commander's subordinates should obey.[250] Army authorities had the habit of amnestying rebel officers, facilitating the occurrence of new revolts.[251]

Tenentism was still the product of military modernization; the core of the tenentist generation were the lieutenants trained in Realengo in 1918–1919.[252] The Military School of Praia Vermelha's tradition of political agitation lived on in its successor schools, despite establishment efforts to root it out. Furthermore, officers saw themselves as a moral elite, superior to civilians, which education reforms sharpened by strengthening their identity.[253] The generals blamed civilian manipulation for the revolts, but the lieutenants "were not partisan men, but political-military action officers".[35]

Other schools also had political impact. At the General Staff School, the environment had a "looser" hierarchy and kept student officers for three years in the federal capital, exposed to politics. At the school itself, "themes of national importance (industrial issue, mineral issue, insertion in global capitalism, etc.)" were addressed in admission tests, conferences and lectures, some given by civilians.[254] Analogously to Realengo among officers, the School of Infantry Sergeants intended to avoid political contagion among sergeants, but the opposite result was achieved, leading to new revolts in the Vargas Era.[255]

Modernization was linked to revolts, and conversely, revolts interfered with modernization. The effect was negative: from 1922 to 1927, the period of the lieutenant uprisings, the Armed Forces' budget suffered cuts. President Artur Bernardes (1922–1926) paralyzed Army Aviation for fear of being bombed.[256] Human, material, and financial resources that could have been used at the Military School of Realengo were spent fighting the Prestes Column,[257] and the discredit created by the lieutenant revolts increased the population's non compliance with mandatory military service.[258]

Consequences after 1930

Universal conscription and the reform of the General Staff made possible a new type of military interventionism after 1930, a "moderating intervention", to be conducted by the "institution-soldier"; until then, the army did not have the institutional will, doctrine or capacity to be a "Moderating Power". Elaborated by military thinkers such as Bertoldo Klinger and Góes Monteiro, this doctrine provided for the political action of the High Command, with all the weight of the institution at its disposal. The first examples of this intervention were the coup that ended the First Republic, on 24 October 1930, and the 1937 coup d'état. General Staff officers came to have a broad concept of national defense and mobilization, covering topics such as strategic industries. Thus, the army's scope of action was much greater. The army's rapprochement with industrial economic groups was already visible since 1916, when the National Defense League was created.[259][260]

Officers trained during this period combined professionalism with interventionism, considering it necessary to act in politics to obtain the army they wanted.[261] French influence convinced officers that military power and national development were linked.[71] Over time, the military became aware of being an elite body within the state, more modern than civil servants, contributing to the sense of superiority and the willingness to be pioneers in modernization.[262]

The increase in personnel, by itself, already increased the army's political power;[201] moreover, in 1930 the army had a better internal structure, professional training of officers and enlisted men, a centralized decision-making process, and clearer objectives. But isolated political interventions, such as that of the tenentists, were weak and broke up the institution.[36] It took a hardening of discipline in the lower echelons to keep them under the control of the highest body, the General Staff of the Army.[90] The strictest discipline was codified by the Disciplinary Regulations of the Army (RDE) and the Internal Regulations for Instruction and General Services (RISG), which came into force in 1920.[90][263] Rebellious movements from the Estado Novo onwards were led by generals.[264]

Notes

- On 4–5 November 1904 there was a border skirmish against Peru in the vicinity of Seringal Minas Gerais, Acre (Donato 1987, p. 495).

- The caption reads: "Soldier: I am now in the third company of the twentieth battalion of the fifth regiment of the third brigade of the eighth region... Sailor: Enough! That way you consume all the time off just saying where you are posted!"

- Caçadores belonged to the infantry and fought like any other infantry battalion since the Paraguayan War. See Castro, Adler Homero Fonseca de. "Notas sobre o armamento na Guerra do Paraguai". Biblioteca Nacional. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020.

- According to the testimony of Setembrino de Carvalho, upon completing the course, the "bachelors" sought the military teaching to escape the barracks (Ferreira 2014, p. 79). In the Acre War, officers assumed public offices before boarding, leaving their units short-handed (McCann 2009, p. 126).

- McCann 2009, p. 321. Savian 2020, p. 44-45 gives a figure of 76,821 planned men for 1921 ("including only infantry, cavalry, artillery and engineering officers; and soldiers (except musicians), infantry, cavalry, field and coastal artillery, and engineering units, in addition to those of the Assault Car Company, aviation squadrons and special contingents").

- Spears last saw practical combat use in the Federalist Revolution, but they came to be used in Canudos and new spears were acquired in the 1900s. See Castro, Adler Homero Fonseca de (1994). "A lança: a arma do centauro dos pampas". Armaria (13): 6–9..

- The first Brazilian Mausers were the 1894 or 1895 "models", designed in 1884, and the second were the 1908 models, designed in 1898. In Brazil, the model number refers to the year of importation (Viana 2018, p. 46-47 and 54-55).

- The Madsen guns returned to the factory for conversion to the same caliber as the rifles. (Reolon 2020, p. 26). After the war, as it was no longer possible to import from Germany, Vz. 24 rifles were purchased in Czechoslovakia (Reolon 2020, p. 46).

- Purchases from Schneider were 25 batteries of 75mm C/18.6 mountain guns, 1919 model, and a battery of 155mm howitzers, 1917 model. Saint-Chamond supplied three batteries of 75mm field guns C/36, 1920 model. See Fortes, Hugo Guimarães Borges (2000). "O rearmamento do Exército Brasileiro no final da década de 1930". A Defesa Nacional. 86 (787): 62.

- The Coxipó Gunpowder Factory, in Cuiabá, ended its activities in 1906. The Mato Grosso War Arsenal had its companies of Military Workers and Apprentice Artificers extinct in 1899 and declined in relevance until its extinction was reported in the local press in 1916. See Crudo, Matilde Araki (2005). Infância, trabalho e educação: os aprendizes do Arsenal de Guerra de Mato Grosso (Cuiaba, 1842-1899) (Thesis). Campinas: Unicamp. and Carvalho, Ednilson Albino de (2005). A Fábrica de Pólvora do Coxipó em Mato Grosso (1864-1906) (Thesis). Cuiabá: UFMT.

References

Citations

- Savian 2020, p. 60.

- Schwarcz & Starling 2015, cap. 13.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 21-22.

- McCann 2009, p. 40-41 e 308-309.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 34.

- McCann 2009, p. 15 e 312.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 60.

- McCann 2009, p. 41.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 80-81.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 52-53.

- McCann 2009, p. 13.

- Savian 2020, p. 209.

- McCann 2009, p. 153.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 57-59.

- McCann 2009, p. 10-11.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 24.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 372.

- Sena 1995, p. 30.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 58.

- McCann 2009, p. 101.

- Oliveira 2013, p. 139.

- Donato 1987, p. 163 e 170.

- McCann 2009, p. 327.

- Donato 1987, p. 166-167.

- McCann 2009, p. 185.

- Donato 1987, p. 172.

- Rodrigues & Franchi 2022, p. 95.

- Rodrigues & Franchi 2022, p. 44.

- Rodrigues & Franchi 2022, p. 97.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 59.

- Rodrigues 2008, p. 56.

- Rodrigues 2008, p. 94.

- Lemos 2014, p. 59.

- Donato 1987, p. 172-184.

- Morais 2013, p. 170-172.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 59.

- McCann 1980, p. 112-113.

- Pedrosa 2018, p. 134.

- Lemos 2014, p. 57-58 e 74-75.

- Svartman 2012, p. 285.

- Magalhães 1998, p. 313 e 320-323.

- McCann 2009, p. 139.

- Rodrigues 2008, p. 95-96.

- Lemos 2014, p. 44.

- Daróz 2016, “A Reforma Hermes”.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 65 e 105.

- Beattie 1996, p. 451-455.

- McCann 2009, p. 151.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 231-232.

- McCann 2009, p. 144.

- Morais 2013, p. 162-163 e 168.

- Marcusso 2012, p. 88.

- Rodrigues 2008, p. 114.

- Rodrigues 2008, p. 63.

- McCann 2009, p. 217.

- Marcusso 2012, p. 153.

- McCann 2009, p. 229 e 243.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 214.

- Lemos 2014, p. 60-61.

- & Bellintani 2009, p. 246-252.

- Lemos 2014, p. 44-45 e 74-75.

- Lemos 2014, p. 77-78.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 253.

- Lemos 2014, p. 227.

- Morais 2013, p. 166.

- McCann 2009, p. 270.

- Lemos 2014, p. 226.

- Lemos 2014, p. 227-231.

- Pedrosa 2018, p. 43.

- Mathias & Guzzi 2010, p. 43.

- McCann 2009, p. 326.

- McCann 1980, p. 112.

- Lemos 2014, p. 40.

- Bento 1989, p. 20.

- McCann 2009, p. 264.

- McCann 2009, p. 215-216 e 223.

- Ranquetat Júnior 2011, p. 11-12.

- McCann 2009, p. 222-223.

- Reckziegel & Luiza 2006, p. 94-96.

- Heinsfeld 2008.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 213, 239-242 e 269.

- McCann 2009, p. 327-329.

- Assunção 2022, p. 23.

- Pedrosa 2018, p. 133.

- McCann 2009, p. 272, 281 e 321.

- Cruz Neto 2015, p. 79.

- McCann 2009, p. 39-40 e 282-283 e 304.

- Arquivo Nacional 2019.

- McCann 2009, p. 40.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 29.

- McCann 2009, p. 143.

- McCann 2009, p. 249.

- Amaral 2007, p. 50-51.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 204.

- Magalhães 1998, p. 324.

- McCann 2009, p. 304.

- McCann 2009, p. 339.

- Pedrosa 2018, p. 135.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 366.

- Pedrosa 2020, p. 40 e 52.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 105.

- Magalhães 1998, p. 313.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 60-61.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 65.

- Souza 2018, p. 94-95.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 367-369.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 368 e 370.

- McCann 2009, p. 184.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 386.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 370-373.

- Pedrosa 2018, p. 162-186.

- Rodrigues 2013, p. 54-55.

- Faria & Pedrosa 2022.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 313.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 76.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 60.

- Magalhães 1998, p. 323.

- Sena 1995, p. 25.

- Sena 1995, p. 26.

- McCann 2009, p. 110 e 141.

- McCann 2009, p. 85-86.

- Rosa 2016, p. 15.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 71.

- McCann 2009, p. 140.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 106.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 52-56.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 69-70.

- McCann 2009, p. 140-141.

- Rosa 2016.

- Beattie 1996, p. 455.

- Rosa 2016, p. 47.

- McCann 2009, p. 234-235.

- Beattie 1996, p. 468-469.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 283 e 312-313.

- McCann 2009, p. 234.

- McCann 2009, p. 296-300.

- "Law No. 1,860 of 4 January 1908". Law No. 1,860 of 4 January 1908.

- McCann 2009, p. 296-300 e 321.

- Zimmermann 2013, p. 38.

- Rodrigues 2013, p. 62.

- Rodrigues 2013, p. 49.

- Zimmermann 2013, p. 37.

- Rodrigues 2013, p. 61-62.

- Araújo & Ferreira 2019, p. 9.

- Rodrigues 2013, p. 62-67.

- Araújo & Ferreira 2019, p. 10-14.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 374.

- McCann 2009, p. 12.

- Rodrigues 2008, p. 203.

- McCann 1980, p. 111.

- Roesler 2015, p. 32-33.

- McCann 2009, p. 44.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 82-83.

- Morais 2013, p. 153.

- McCann 2009, p. 40-41.

- Roesler 2015, p. 37.

- Ferreira 2014, p. 78-79.

- Morais 2013, p. 156.

- McCann 2009, p. 120.

- Roesler 2015, p. 56-58.

- Rodrigues 2008, p. 70-72.

- Svartman 2012, p. 283-284.

- Roesler 2015, p. 58-59.

- Marcusso 2017, p. 14, 73 e 281.

- Grunnenvaldt 2005, p. 111.

- Roesler 2015, p. 65.

- Roesler 2015, p. 75-81.

- Marcusso 2012, p. 194-195.

- Grunnenvaldt 2005, p. 151-152.

- Marcusso 2012, p. 115.

- Svartman 2012, p. 287.

- Marcusso 2012, p. 125.

- Rodrigues & Franchi 2022, p. 308-317.

- Roesler 2021, p. 269.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 341.

- Marcusso 2017, p. 15 e 281-282.

- Marcusso 2012, p. 173-174.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 342-351.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 211 e 265-266.

- Morais 2013, p. 167.

- Marcusso 2017, p. 24.

- McCann 2009, p. 307.

- McCann 2009, p. 276.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 36-37.

- Ferraz 2021, p. 146-147.

- McCann 2009, p. 311.

- McCann 2009, p. 252 e 338.

- Roesler 2015, p. 114.

- Marcusso 2012, p. 170.

- Bento 1989, p. 17.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 30.

- McCann 2009, p. 125.

- Moura 2013, p. 292.

- McCann 2009, p. 159.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 203.

- McCann 2009, p. 262-263.

- Savian 2020, p. 44-45.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 217.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 218.

- McCann 2009, p. 294 e 608-609.

- McCann 2009, p. 236.

- McCann 2009, p. 43.

- Cruz Neto 2015, p. 71.

- Mello 2014, Apêndice B, As armas da Guerra.

- Reolon 2020, p. 26-27.

- Daróz 2018, p. 38-39.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 213.

- McCann 2009, p. 334.

- Cruz Neto 2015, p. 80.

- Magalhães 1998, p. 336.

- Reolon 2020, p. 45.

- Viana 2018, p. 49.

- McCann 2009, p. 281.

- Domingos Neto 2007, p. 235-236.

- Savian 2013, p. 6.

- McCann 2009, p. 319.

- Daróz 2018, p. 46-47.

- Assunção 2022.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 377.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 321.

- Magalhães 1998, pp. 337–338.

- Magalhães 1998, p. 317.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 226.

- Andrade 2016, p. 13.

- McCann 2009, p. 238.

- McCann 2009, p. 238-241 e 273-276.

- Saes 2011, p. 127.

- McCann 2009, p. 112-113.

- Rodrigues & Franchi 2022, p. 320.

- Viana 2010, p. 59-61.

- Corrêa-Martins 2011, p. 8.

- Santos 2021, p. 10-11 e 16-17.

- McCann 2009, p. 144-145.

- Bonates & Moreira 2016, p. 232.

- Bonates & Moreira 2016, p. 224.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 235-236.

- Bonates 2018.

- McCann 2009, p. 286 e 329-334.

- Meucci 2009.

- Marques 2019, p. 42-43.

- Pedrosa 2022, p. 370.

- McCann 2009, p. 300-301.

- McCann 1980, p. 113.

- Bellintani 2009, p. 69.

- Svartman 2012, p. 289-292.

- Saes 2011, p. 126.

- Rodrigues 2008, p. 98-99.

- McCann 2009, p. 277.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 38-43.

- Mathias & Guzzi 2010, p. 44.

- McCann 2009, p. 342.

- McCann 2009, p. 252 e 600-601.

- Svartman 2012.

- Marcusso 2017, p. 283.

- Rodrigues 2013, p. 67.

- Waldmann Júnior 2013, p. 34-35.

- McCann 2009, p. 316.

- McCann 2009, p. 355.

- Carvalho 2006, p. 29, 41-43 e 59-60.

- McCann 2009, p. 15.

- Svartman 2012, p. 293.

- Inácio 2000, p. 135.

- Rodrigues 2013, p. 66-67.

- Morais 2013, p. 173.

Bibliography

- Books

- Andrade, Israel de Oliveira (2016). "Base Industrial de defesa: contextualização histórica, conjuntura atual e perspectivas futuras". Mapeamento da Base Industrial de Defesa (PDF). Brasília: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada.

- Bento, Cláudio Moreira (1989). O Exército na Proclamação da República (PDF). Rio de Janeiro: SENAI.

- Carvalho, José Murilo de (2006). Forças Armadas e Política no Brasil (2 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Ed.

- Daróz, Carlos Roberto Carvalho (2016). O Brasil na Primeira Guerra Mundial: a longa travessia. São Paulo: Contexto.

- Donato, Hernâni (1987). Dicionário das batalhas brasileiras – Dos conflitos com indígenas às guerrilhas políticas urbanas e rurais. São Paulo: IBRASA.

- Faria, Durland Puppin de; Pedrosa, Fernando Velôzo Gomes (2022). "Hierarquia militar brasileira - Exército". Dicionário de história militar do Brasil (1822-2022): volume II. Rio de Janeiro: Autografia.

- Ferraz, Francisco César Alves (2021). "O Serviço militar brasileiro na hora da verdade: a preparação para o combate em tempos de paz e a participação brasileira na Campanha da Itália". Fuerzas Armadas, fronteras y territorios en Sudamérica en el siglo XX: Perspectivas y experiencias desde Argentina y Brasil. La Plata: UNLP.

- Magalhães, João Batista (1998). A evolução militar do Brasil (2 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército.

- McCann, Frank (2009). Soldados da Pátria: história do Exército Brasileiro, 1889–1937. Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo: Biblioteca do Exército e Companhia das Letras.

- Mello, Frederico Pernambucano de (2014). A guerra total de Canudos (3 ed.). São Paulo: Escrituras.

- Moura, Aureliano Pinto de (2013). "O Exército Brasileiro na Insurreição do Contestado". Cem anos do Contestado: memória, história e patrimônio. Florianópolis: MPSC.

- Pedrosa, Fernando Velôzo Gomes (2022). "Organização das forças do Exército Brasileiro na República". Dicionário de história militar do Brasil (1822-2022): volume II. Rio de Janeiro: Autografia.

- Rodrigues, Fernando da Silva; Franchi, Tássio (orgs.) (2022). Exército Brasileiro: perspectivas interdisciplinares (1 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Mauad.

- Savian, Elonir José (2020). Legalidade e Revolução: Rondon combate tenentistas nos sertões do Paraná (1924/1925). Curitiba: edição do autor.

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz; Starling, Heloisa Murgel (2015). Brasil: uma biografia. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Articles

- Araújo, Gustavo de Freitas; Ferreira, Ramon Vilas Boas (2019). "A formação dos sargentos no Exército Brasileiro no contexto da Missão Militar Francesa". Revista do Exército Brasileiro. 155 (2).

- Arquivo Nacional (18 July 2019). "Secretaria de Estado dos Negócios da Guerra". Memória da Administração Pública Brasileira. Retrieved 25 February 2023.